Book Review: Early Christian Attitudes toward Images by Steven Bigham (2 of 4)

This blog posting is a continuation of an earlier review of Fr. Steven Bigham’s book. In this posting I will be reviewing and interacting with Bigham’s arguments in Chapter 2.

Chapter 2 examines early Jewish attitudes toward images. This is important because modern Protestant iconoclasm assumes that the early Christians inherited from the Jews a hostile attitude towards images. However, if it can be shown that there existed an open attitude toward images among early Jews then the basis for the hostility theory becomes problematic.

Steven Bigham notes that a distinction needs to be drawn between figurative art and pagan idols. He presents Jean-Baptiste Frey’s theory that an alternation took place between a rigorist and less rigorous interpretations of the Second Commandment (pp. 22-23). This challenges the implicit assumption that Jewish opposition to images to be fixed and unchanging. This new approach allows for more flexible readings of the biblical, rabbinical, and historical data. It is suggested that a liberal attitude towards images existed from the period of monarchy to the exile, then a rigorist attitude from the restoration to the Hellenistic period. Later, an accepting attitude was found among the Amoraïm, the successors to the Pharisees.

Biblical Evidences

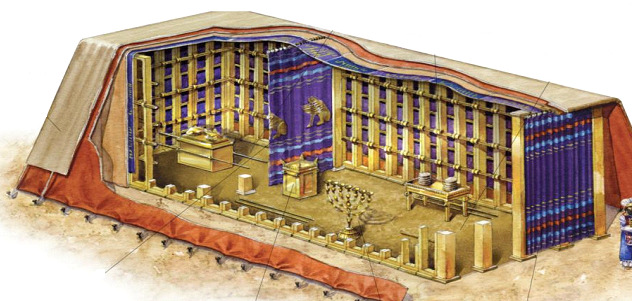

In sub-section 3 (pp. 22-32), Bigham reviews the biblical evidence for the use of art and images in Israelite worship: Exodus, Numbers, 1 Kings, Ezekiel, and Ecclesiasticus. In considering the Old Testament evidence, Bigham excludes passages relating to pagan idolatry and examines passages pertaining to Israelite worship (p. 26).

The Tabernacle in Exodus

Bigham finds it significant that Exodus which contained the Second Commandment (Exodus 20:2-6) also contained divine instructions for the construction of the golden cherubim over the Ark of the Testimony (Exodus 25:1-22), as well as the manufacture of curtains embroidered with cherubim (Exodus 26:1, 31). Bigham notes,

Placed so close to God himself and so intimately linked with the worship of the true God, the cherubim could never be separated from that worship and become themselves the object of misdirected, idolatrous worship. The cherubim on the Ark of the Testimony are a real problem for the advocates of rigorism, because God himself ordered Moses to have them made. The untenable contradiction in the divine commands disappears if we assume a relative interpretation of the 2nd Commandment that allows for non-idolatrous, liturgical images (p. 26).

All too often Protestant iconoclasm has equated idolatry with images, but this is too simplistic a definition. In his examination of the passage on the bronze serpent, Bigham notes that a sculpted image can be used in a non-idolatrous way. In response to the poisonous snakes sent to punish the Israelites, God ordered the making of a bronze serpent as a means of healing (Numbers 21:4-9). Later, King Hezekiah destroyed the serpent because the Israelites had begun to misuse it (2 Kings 18:1-4). Bigham notes:

This episode shows how an object, an image, normally not considered to be a idol, can become one. Idolatry is determined by a person’s intention and attitude toward an image, and not by the image itself (p. 27; emphasis added).

What Bigham has done here is to clarify the difference between religious art and idolatry. Furthermore, he has resolved an apparent contradiction in the Old Testament. His contextual understanding of the Old Testament passages avoids the difficulties caused by the more rigorist interpretations of the Second Commandment which would clash with subsequent passages that mandate the making of religious art.

In doing so, Bigham has rendered a tremendous service to Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. In any conversation on the Second Commandment and the proper role of images in worship, it is important that a balanced and biblically based definition of idolatry be established at the outset. If the two sides start from disparate definitions, the conversation will go nowhere. One question for the Reformed Christians and Evangelicals to consider is whether Bigham’s understanding is both biblical and balanced. If not, then they should put forward an alternative definition for the Orthodox to consider.

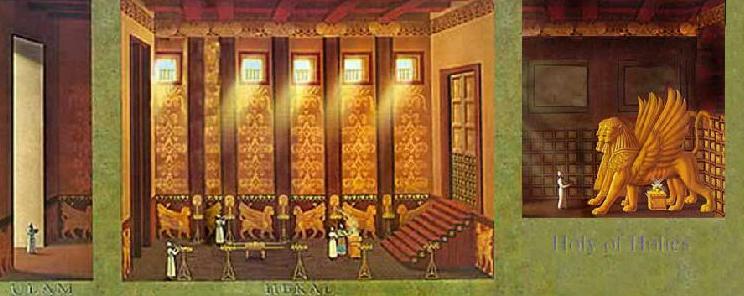

Solomon’s Temple

Bigham describes Solomon’s Temple in 1 Kings to be “a veritable art gallery and a nightmare for the advocates of the rigorist interpretation” (p. 28). King Solomon did not just replicate the Mosaic Tabernacle, but expanded and elaborated on the religious art work in connection with the worship of Yahweh. He had two enormous cherubim sculpted out of wood and overlaid with gold (1 Kings 6:23-28).

Solomon also had cherubim, palm trees, and open flowers carved on all the Temple walls and on the door to the Holy of Holies (1 Kings 6:29-31). Solomon made a molten sea which was placed over twelve statues of bulls (1 Kings 7:23-26). Furthermore, Solomon ordered the making of movable stands on which were carvings not just of cherubim, but also of lions and bulls (1 Kings 7:27-37).

The laudatory tone with which Solomon’s construction of the Temple for Yahweh was presented and the absence of any criticism makes 1 Kings quite problematic for those who hold to the iconoclastic position.

Solomon’s throne likewise was a huge work of art comprised of ascending steps with sculpted lions on both sides of each step leading to the throne (1 Kings 10:18-20). While less holy than the Temple, the throne was nonetheless the seat of the Lord’s anointed. This biblical passage points to an acceptance of images beyond the Temple into “secular” domains.

The favorable attitude among Jews continued into the post-exilic period. Bigham found in I Maccabees 1:22 and 4:57 evidence that the front of the Second Temple (520-515 BC) had been decorated with gold.

Ezekiel’s vision of the restored Temple continues the favorable attitude towards the use of images. As a prophecy it is significant because it extends the orthodoxy of religious images from the Mosaic Tabernacle of the past into the future worship of the Messianic Age, i.e., the Christian era. What is astounding is the profusion of images in Ezekiel’s future temple.

As far as the nearby wall of the inner and outer courts and along upon the wall all around within and without were depicted cherubim and palm trees, between cherub and cherub. Each cherub had two faces, the face of a man toward a palm tree on one side, and the face of a lion toward a palm tree on the other side. Thus it was depicted throughout the house all around. From the floor to the threshold, the cherubim and the palm trees were interspersed upon the walls (Ezekiel 41:17-20; OSB).

Taken together, the combined witness of passages across the Old Testament–from the time of Moses, the royal kingdom, and the prophetic tradition–presents an immense challenge to those who hold to the rigorist interpretation of the Second Commandment which disallows any and all forms of images in connection with the worship of Yahweh.

Non-Religious Images

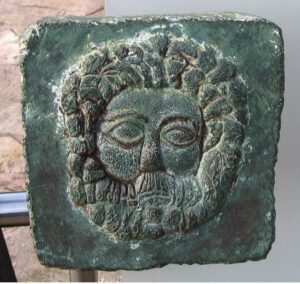

In sub-section 5 (pp. 34-41), Bigham notes that additional evidence in support of Jewish tolerance or acceptance of images can be found in coins decorated with symbols like wreaths, horns of plenty, palms, cups and amphorae. It seems that these were accepted by Jewish authorities and rabbis. Similarly, Bigham found in Josephus’ The Antiquity of the Jews evidence that a certain prominent Jew, Hyrcanus, built a castle decorated with animals engraved on its walls (Bigham p. 37).

Carving of Lioness on Hyrcanus Palace

Josephus and Philo

In sub-section 6 (pp. 41-66), Bigham examines the evidence used to support the notion that first century Judaism prohibited “images of animate beings” on the basis of the Jewish Law. Two early sources, Josephus and Philo, have been used to bolster the claim that first century Judaism was by and large iconophobic. Bigham notes that behind this iconophobia was hostility to symbols of Roman rule. In other words the first century rigorist reading of the Second Commandment may be rooted just as much in politics as in religion (p. 44). Josephus in his Antiquities XVIII, III, 1, explained that Jewish opposition to the Romans display of the emperor’s image on military standards was due to the Second Commandment. However, Bigham notes:

We can also see Josephus’s motivation for painting the incident in religious, rather than its obvious political colors: The Roman authorities for whom Josephus wrote would be less offended by an insult to the emperor’s image based on the Jews’ well-known sensitivity in religious matters. In any case, Josephus’s presentation of the Law – “our law forbids us the very making of images” – is simply wrong since previous and subsequent Jewish history shows that such images were made and accepted under certain conditions (p. 45).

Recent Archaeological Discoveries

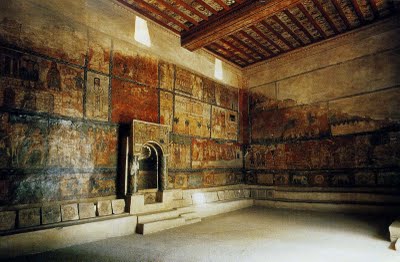

Dura Europos Synagogue. Source

In sub-section 7 (pp. 66-78), Father Bigham devotes several pages (pp. 66-70) to the archaeologists’ discovery of the Jewish synagogue in Dura Europos in 1932. Its complete burial allowed it to be preserved virtually intact. Due to the widespread assumption at the time that early Judaism was aniconic, the building was initially mistaken for a Greek temple.

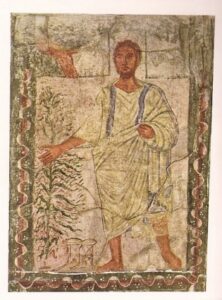

Image of Baby Moses – Dura Europos Synagogue. Source

The Dura Europos synagogue has profoundly challenged many misconceptions of early Jewish worship. The Dura Europos synagogue was not an isolated exception; other ancient synagogues had figurative arts (p. 67).

Moses and Burning Bush – Dura Europos. Source

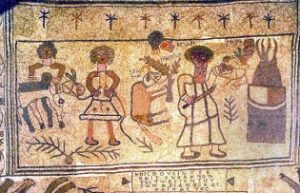

The Binding of Isaac – Beth Alpha. Source

This leads Bigham to write:

… it seems increasingly clear that Judaism led the way in developing figurative art and that Christianity followed, at least at the beginning. We have already seen that this hypothesis is upheld by many scholars. Even in areas other than art, we see the same phenomenon: early Christianity often modeled itself on its Jewish parent. “For the ancestry of most elements of early church worship, we must look to the synagogue rather than the home … (C. Filson)” (Bigham p. 68)

These archaeological evidences present serious problems for those who hold to the hostility theory, especially on the assumption that early Judaism was uniformly aniconic and iconophobic (Bigham p. 89). However, if first century Judaism accepted religious art, then it makes sense that the early Christianity reflected its Jewish roots. It can then be argued that it is the iconoclastic hostility theory that represents an alien intrusion into Christian history. The hostility theory was easy to uphold when the evidence was buried in the ground but when archaeological discoveries over the past century unearth these evidences that theory lost its foundation.

Religious Art in Early Jewish Synagogues

In addition to the startling discoveries at Dura Europos, there are other evidence of religious art in Jewish synagogues.

Zodiac – Synagogue Mosaic on Mt. Carmel. Source

The zodiac mosaic at Beth Alpha was not an isolated example. Other similar zodiacs have been found in Israel, e.g., Hammath Tiberias on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Naaran near Jericho, Sepphoris slightly north of Nazareth, En Gedi by the Dead Sea, and Huseifa near Mt. Carmel.

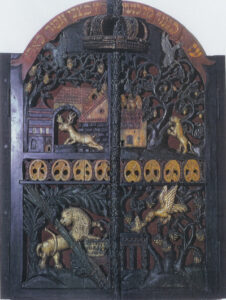

Religious Art in Medieval Judaism

An examination of religious art in medieval Judaism shows an attitude more accepting of religious art than that found in the Reformed tradition. One example is the carving of images on the ark in the Butzian Synagogue in Cracow, Poland.

Findings and Conclusion

Fr. Steven Bigham has conducted a wide ranging review of evidence about early Jewish attitudes toward images. The evidences include both biblical and extra-biblical sources, as well as secular literary sources and archaeological evidences. Bigham notes that the evidence is not conclusive, but it does call into question the assumption that early Judaism was uniformly and rigidly opposed to images. Early Jewish acceptance of images even in the context of synagogue worship lays the historical basis for the acceptance of images in early Christian worship.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments