Icon – Saint Mark Coptic Orthodox Church – Honolulu, Hawaii

[Note: I first met Genesis Sanchez at the Orthodox Christian Fellowship at UC Berkeley. At the time he was an inquirer, since then he has converted, graduated, and grown into a fine Orthodox Christian. In light of the increased attention given to Oriental Orthodoxy on the Internet, I thought that Genesis’ reflection on his interactions with Oriental Orthodoxy would be of interest to readers of the OrthodoxBridge blog. Robert Arakaki]

Family I didn’t know that I have, but family who I have not fully reconciled with yet by Genesis Sanchez

This is how I can summarize my experiences with the Oriental Orthodox tradition for over a decade. The following will be a reflection of my personal experiences as an Eastern Orthodox Christian (EO) with the Oriental Orthodox (OO)tradition. It will not be a treatise on our Christological distinctions as there are already many out there of greater quality.

First Impressions – Research

I am a Filipino American [Fil-Am] born and raised in the Bay Area (California). I grew up in the Pentecostal tradition and my parents raised me in the hopes that I would one day become a Pentecostal preacher.

My first impressions of the Oriental Orthodox were quite negative. I was just beginning to study ancient Christianity as a 17-year-old. I began by learning the ancients, from Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, under the guidance of a man would later become my Orthodox godfather, to gain foundational philosophical knowledge to personally work through the theological controversies which would be crucial in my decision for which ancient Christian community to join, whether Oriental Orthodox (OO), Eastern Orthodox (EO), or Roman Catholic. Under his guidance, I went from the Greek ancients to working through the writings of St. Cyprian, and afterward, Severus and St. John of Damascus. It is important to note that my godfather is Eastern Orthodox and, therefore, although I read through key Oriental and Eastern Orthodox Fathers, our theological discussions ultimately convinced me that the Eastern Orthodox position was the most tenable one, a position that I still hold today, especially when considering the question of Christ’s divine and human wills. In short, having made my decision to continue with Eastern Orthodox theology, I felt like I no longer needed to pay attention to the Oriental Orthodox. I was subsequently received into Holy Orthodoxy at a small Greek Orthodox parish in the Bay Area.

UC Berkeley

University Days – Unexpected Closeness

However, I then began my time at UC Berkeley where Oriental Orthodox students, primarily from Coptic and Ethiopian churches, regularly attended the Orthodox Christian Fellowship weekly liturgy and fellowship nights. It was here where I became very close with Oriental Orthodox Christians. I found myself attending their own university gatherings and praying with them, although I still believed that EO theology was more complete, and not at all identical with theirs, and therefore I even considered them heterodox. However, I had no issues praying with them as I did not consider them heretics, and also could not help feeling a strange kinship with them. Now, I have to admit how inconsistent I was.

This inconsistency grew in complexity post-graduation as, by this time, I had gained even more close Coptic friends, many of whom I am still in contact to this day. I was deeply touched by how genuine, friendly, pious and fun they are. Even now, I consider many of these Coptic friends some of the best people I know. It was also around this time that I became aware of how many EO and OO priests in the Bay Area, and these were highly regarded and even saintly clergy, gave communion to each other’s laity, especially for mixed OO and EO couples. I honestly did not think much of this but by this point, all of the subconscious disregard I had for Oriental Orthodox still lingering in the recesses of my heart had vanished. Instead, for me the Oriental Orthodox did matter. Somehow, without articulating it, I did genuinely feel them to be family. However, I still believed there were issues in their theology.

Chengdu China – Source

From Berkeley to China

Two key moments transpired which revealed a tension I did not realize had become quite serious inside of me. The first was when a Coptic priest at their Hayward, California, parish told me that the Copts accept St. John of Damascus’ two natures formula. I was shocked and asked myself immediately, “So, what are we still arguing about?”

The second moment was when I had moved to China a few years later, and chanced upon the Agreed Statements from the Joint Commission of the Theological Dialogue Between the Orthodox Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches. [See Resources below] In short, these are a series of dialogues between several EO and OO churches that have produced statements of agreements over each other’s Christologies. I was very excited by this and thought it was an official act of reunion between our two families, but little did I realize we are still far from it. One reason is that the agreed statements are not ecumenical on either side. That is, not all EO and OO patriarchates have agreed on this statement, although a good number on both sides have. However, the excitement I gained from this discovery stayed with me for many years.

Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University

Oxford – Another Surprising Deeper Engagement

This excitement—this spark—didn’t actually lead to anything concrete for a few years. It wasn’t until I left China and began my master’s studies at Oxford University that things gained momentum. I was studying teacher education, which I like to jokingly describe as “learning how to give teachers homework.” I had enormous flexibility in choosing my dissertation topic, but I genuinely didn’t know what direction to take.

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox community – Oxford University

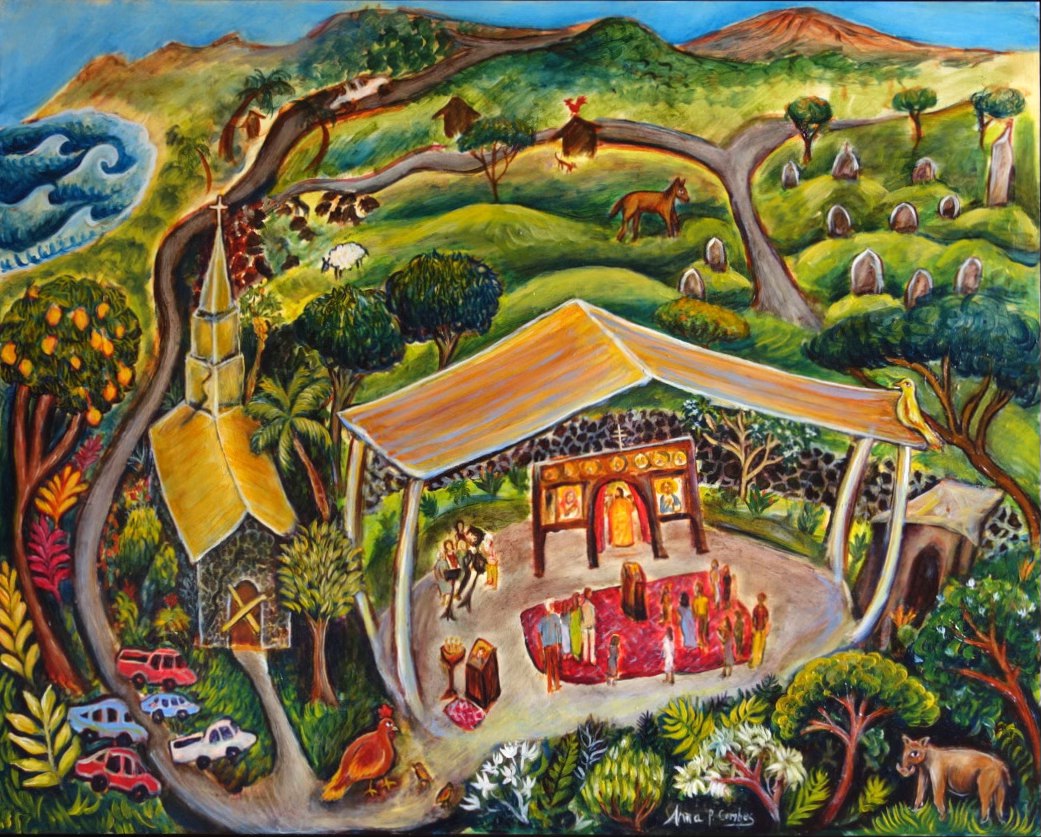

Everything shifted upon my arrival in England. One evening, after attending a Vespers service at the Greek Orthodox parish of the Holy Trinity that the late, great Metropolitan Kallistos helped establish, I had a chance encounter with an Ethiopian Fulbright fellow. I don’t remember exactly how the conversation unfolded, but I ended up telling him that I was doing my master’s in education and that I was particularly interested in religious education. That’s when he introduced me to the Ethiopian Church’s remarkable educational tradition, particularly the Qene poetry system.

In the Qene poetry discipline, students learn to compose improvised hymns using Ge’ez—something he described in a way that made me think of it loosely as an “African Hebrew.” Under this tradition, children begin their training at a very young age and can continue developing their skills well into old age, eventually becoming master hymnographers capable of freestyling deeply theological poetry. I was stunned. I told myself, “I have to go to Ethiopia.”

Weekday training for Qene students

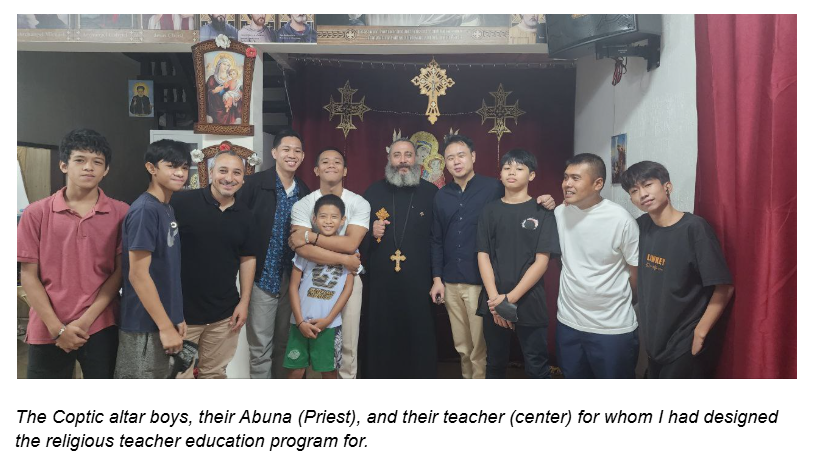

This desire eventually became my master’s project. Initially, I wanted to work with Eastern Orthodox communities in the Philippines and design educational programs for them. But strangely, I found the Eastern Orthodox churches there either difficult to approach or simply not focused on educational initiatives. It wasn’t until I discovered the Coptic Orthodox community in the Philippines, and reached out to them, that I found a group truly eager for collaboration. In light of their enthusiasm, I decided I would design religious education teacher-training programs for the Coptic Church.

When it came time to finalize my dissertation topic, the Ethiopian tradition resurfaced in my mind. I realized that if I wanted to explore how to train religious educators—not just technically but spiritually—I needed to learn from the traditions that cultivate deep theological insight through disciplined creative expression. So, during my second and final year at Oxford, I arranged to travel to Ethiopia to study this tradition firsthand.

But I didn’t stop there. As an Eastern Orthodox Christian, I wanted to draw from both the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox worlds. For me, their educational traditions felt more similar than different, especially in spirit. So alongside Ethiopia, I set my sights on Mount Athos. There, I discovered that the Holy Mountain actually has a school for boys, where students receive their primary and secondary education right inside the monastic republic. Yes—there are literally boys who grow up going to school on Mount Athos! In 2017, I went on a pilgrimage to Simonopetra and Vatopedi. Then in 2022, I stayed at Simonopetra then the Skete of Saint Andrew.

In the end, my research journey led me to both Ethiopia and Mount Athos, allowing me to draw from two ancient, living traditions of formation. My aim was not only to understand how to teach religious education teachers, but to glimpse the deeper spiritual frameworks that shape how both Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox communities transmit faith across generations. See Genesis Sanchez – MA Thesis.

Throne of the Qene Master in the classroom

Meeting “Four Eyes” Ezra

There is so much I could write about what I saw in both countries: Mount Athos and Ethiopia. To summarize it, I was blessed to meet with religious education teachers from both sides. But what left a particularly deep impression on me was meeting these Qene scholars face to face.

Lekaleqount Ezra and Genesis Sanchez

Especially significant was meeting an Ethiopian Orthodox religious scholar called Lekaleqount “Four Eyes” Ezra. He had memorized the entire Bible and several Patristic books, therefore gaining the “four eyes” of the Old Testament, New Testament, the Desert Fathers, and other Fathers such as St. Ephraim the Syrian. Lekaleqount Ezra is also known not just for his deep theological knowledge, but for his holiness as well. For me personally, I thought he was a very energetic, youthful, and even fun preacher despite being in his 70s.

Lekaleqount Ezra after back-to-back all-night vigil and a liturgy which started at 8 pm on Saturday and ended at 7 am on Sunday, followed by a 40 minute homely. [Picture on right]

As I came face to face with the depths of the Oriental Orthodox tradition, at one point I asked myself, “Why don’t I become Oriental Orthodox?” This came as a result of the profound interaction and connection with the scriptures and with tradition that I felt like I had not experienced. “Felt” would be the key term for these great moments. I think that I often overlook many parts of my own tradition whenever I find myself carried away by such experiences.

Communion Confusion

It was now time for me to go back to the Philippines to continue working with the Coptic community and helping with their religious education program, designing a program based on what I learned from Mount Athos and Ethiopia and even England, both the Greek Orthodox and Coptic Orthodox communities there. I designed a program to teach the Philippine Coptic communities in collaboration with one of their own religious education teachers who also was a science teacher in his secular career.

Although I had put my heart and soul into the religious education program, I ultimately did not become Coptic. I could write another whole other blog explaining why. However, I don’t think I’ll ever feel the need to be Coptic, especially now. If I could summarize my reasons however, I do think that my EO tradition is more truly Catholic and One that theirs, although my sense is that our Holiness and Apostolicity is as thorough as each other’s. But then again, I am a mere laymen inexperienced in the great mysteries of the spiritual life.

But more importantly, doing these activities, I fell in love with the Coptic people. Even before I launched this program, I already fell in love with them, but now my heart was at pains to reunite with them. Again, this is something that I felt even before I went to Athos and Ethiopia because my volunteer work with the Coptic community already made me feel such.

But at this time, I actually started taking Communion with them. They gave me communion, but when I had left for England, Ethiopia and Athos, I was told by a Coptic priest that I really cannot have Communion with them again, despite the volunteer work I had done for them. The decision was not made by the Coptic priest, who would have been happy, as he later told me, to continue to give me Communion. The decision was made by the Coptic bishop of the Philippines.

Yet upon coming back to the Philippines, I felt an even deeper attachment to the Coptic community, and my wife-to-be at that time also felt the same way. In fact, if the Coptic community still gave me Communion nowadays, I would have become a regular parishioner there. It is one of my favorite parishes in the Philippines.

And what’s even interesting is that after I came back from Ethiopia, I went to a Coptic liturgy after I had a conversation with their Tasuni, which is their term for sister or what they sometimes call a priest’s wife, essentially the equivalent of a presvitera (wife of a Greek Orthodox priest). And there I was hired by a Coptic American business lady to be an HR manager for her company. Sadly, my time with the Coptic company ended in just about a year. I was not a good fit for the company. And it was also at this time that I started having debates with one of my Coptic Orthodox missionary friends. And this has led me to my final and most current reflection and sentiment about the Coptic faith.

Saying Goodbye to Dear Coptic Family

My debates with my Coptic missionary friend were productive, but in a way that I did not expect. It was productive because it revealed to me the problems and difficulties that still remain between our two traditions. Yes, in many ways we are identical. I would say we are 98% in agreement, but how we work out not so much just Christ’s humanity and divinity and their unity, but more so the current state of his divine and human wills is an issue that needs to be resolved before we can have communion with them again. Although quite technical for people outside of our communities, I understand now that these are still important questions. The issue whether Christ has one will or two wills was so important that the Fifth and Sixth Ecumenical Councils met to resolve the controversy. Technically speaking, Eastern Orthodoxy is Dyothelite (Christ has two wills) and Oriental Orthodoxy is Monothelite (Christ has one will).

Saying Goodbye to Father Mina and Tasuni Phoebe

I see that we still have not fully worked out the question especially of an agreement between how we understand the will or wills of Christ. The Copts would still rather confess one will of Christ and we would articulate that he has two wills. Now, bridges and agreements can be made between these, but based on my very intense debates online, on Facebook, through chat, really not the most professional and I would have to say not the most representative of the Coptic tradition as well because I did not seek out to thoroughly dialogue with the greatest Coptic scholars that I could access, but was instead in a sense was the one that was quote-unquote sought out by my missionary friend who had lots of questions about Chalcedonian Christology.

For now, all I can be is a friend, a family, a brother to my fellow Oriental Orthodox, case in point. One of the saddest moments this year in my life here in the Philippines was when my wife and I found out that our dearly beloved friends, the Coptic priest and his wife of the Philippines, were leaving. All of a sudden, they texted us saying that they were leaving. This was one of the most heartbreaking moments in my year in the Philippines. They had become our best friends, family. They spoke during our wedding. And I look back at myself as a 17-year-old studying Oriental Orthodox theology and afterwards thinking no more about it, too, falling in love with the Abuna and his Tasuni, who were a family to us deeper than blood, who had given us communion, and I hope to receive Communion from again, someday, some other place. I would love to help out their church, visit them wherever they may be, because it was in that moment of oneness, of fellowship, that I believe our hearts became one. And if God wills, may this unity happen fully in my lifetime, which would bring me tears of great joy.

by Genesis Sanchez

Resources

First Agreed Statement [1989]

Second Agreed Statment [1990]

Bible Hub. “What is dyothelitism?”

Let’s Talk Religion. “The Ethiopian Orthodox Church Explained.” [34:46]

Recent Comments