John Carpenter brought to my attention his article “Icons and the Eastern Orthodox Claim to Continuity with the Early Church” which was published in the Journal of the International Society of Christian Apologetics Vol. 6 No. 1 (April) 2013.

In it he attempts to refute the Orthodox position on icons by making the following points:

(1) The Orthodox Church claims “unbroken continuity” going back to the Apostles,

(2) The historical evidence shows that icons were not part of the early church, and

(3) Therefore, the Orthodox Church’s claim to “unbroken continuity” is disproved.

There are two basic components in Carpenter’s apologia: (1) the theological which challenge Orthodoxy’s claim to unbroken continuity and (2) the historical which consists of evidence that disprove early Christian usage of icons.

This posting will consist of three sub-sections: Part I which will be theological focusing on the nature of Tradition, Part II which will be historical focusing on the early usage of icons, and Part III which will assess Carpenter’s argument and offer my response to his challenge to Orthodoxy.

Part I. Theological Argument

Is Tradition Static?

John Carpenter understands continuity in Tradition to mean a static continuity that leaves no room for development and growth. In the introduction he writes:

But because Eastern Orthodoxy stakes its claim to legitimacy on “unbroken continuity” with the early church, any proof of significant departure of the Orthodox from the practices of the early church would undermine their claim. To defend their current prominent use of icons, the Orthodox have to assert that their iconography goes back to the Apostles. (p. 108)

Then in his conclusion, Carpenter writes:

A tradition, such as Catholicism, could handle this development by arguing that the church evolved under the direction of the Holy Spirit. But a tradition that stakes its claim on “unbroken continuity” must argue that Eusebius was in error; that he was a rare dissenting voice. But even that doesn’t dismiss the historical evidence that Eusebius’s argument (as well as Canon 36 of the Council of Elvira) constitutes. Even if one argues that Eusebius and Elvira were wrong and hold no authority, both show that, at least, significant leaders in the early church opposed icons. (p. 117)

What Rev. Carpenter wrote reflects a misunderstanding among Protestants as to how Orthodox Christians understand Tradition. This belief that Orthodoxy’s claim “unbroken continuity” leaves absolutely no allowance or room for any development has been a significant impediment to Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. Steven Bigham in Early Christian Attitudes toward Images (2004) counters that false characterization noting:

Few defenders of the idea of Tradition claim that nothing has changed since the beginning of the Church, and everyone recognizes that all the changes that have taken place have not necessarily been for the good. . . . . A healthy doctrine of Holy Tradition makes a place for changes, and even corruption and restoration, throughout history while still affirming an essential continuity and purity. This concept is otherwise known as indefectibility: the gates of hell will not prevail against the Church. This theoretical framework, indefectibility, takes change and evolution into account but denies that there has been or can be a rupture or corruption of Holy Tradition itself (p. 15; emphasis added).

Rev. Carpenter’s static understanding of Tradition raises all sorts of problems. By that definition then the Nicene Creed can be considered an innovative add on. Furthermore, it would imply that the term “Trinity”–which cannot be found in the Bible—can be considered a departure from Apostolic Tradition. Also, for the first several centuries the New Testament canon was an open question with some books included by some churches and other books left out by others. It was not until the Sixth Ecumenical Council formally defined the New Testament canon that the listing was formally closed. All this goes to show that there is an element of elaboration and development of doctrine and practice in early Christianity that does no violence to indefectibility or unbroken-continuity. Carpenter’s portrayal of the Orthodox understanding of Tradition as static is historically incorrect and leads him to set up a straw man argument.

II. The Historical Argument

Old Testament Sources

I was surprised that Rev. Carpenter overlooked one very important source of historical evidence: the Old Testament. The book of Exodus described the incorporation of two dimensional images of the cherubim on the Tabernacle walls and the entrance curtain to the Holy of Holies (Exodus 26). Images of the cherubim were also part of Solomon’s Temple (see 1 Kings 6, 2 Chronicles 3). It can be reasonably hypothesized that Herod’s Temple was adorned in similar fashion with images of the cherubim and other visual ornamentation. We read in Luke 21:5: “Some of his disciples were remarking about how the temple was adorned with beautiful stones and with gifts dedicated to God.” This lavish ornamentation was not an innovation introduced by Herod, but a tradition in Jewish worship going back to Moses. The Old Testament witness presents both a historical and theological justification for images in Jewish worship. Luke 21:5 suggests the continuation of the Jewish tradition of images in worship up to the time of Christ and the Apostles.

Rabbinical Sources

Another major weakness in Rev. Carpenter’s article is his skewed presentation of rabbinical writings. He failed to take into account the diversity among the Jews of Jesus’ time. He quotes extensively from rigorist rabbis who objected to any and all forms of images but left out or overlooked more moderate rabbis. For example we read in Abodah Zarah 33:

If it is a matter of certainty that [statues are] of kings [and hence made for worship], then all will have to concur that they are forbidden. If it is a matter of certainty [that the statues are] of local officials [and hence not for worship], then all will have to concur that they are [made merely for decoration and hence] permitted. (cited in Footnote 101 in Bigham p. 73)

Carpenter overstated the Jewish opposition to the use of images. He writes:

The commitment of second-temple Judaism to build a “fence” around the Second Commandment was such that Jews of the period protested the Roman flags with images and the profile of Caesar on the coins. (p. 110)

Then what are we to make of Mark 12:13-17 where Jesus in a debate asked for a coin with Caesar’s image, held up the coin, and posed the question: “Whose portrait (εικων) is this?” It is clear from this passage that Jesus was not one of the rigorist rabbis, but held to a more moderate interpretation of the Second Commandment. But if we were to go by what Rev. Carpenter had written above then he would have to accuse Jesus of violating the Second Commandment! This puts Carpenter in an untenable position.

The Dog That Didn’t Bark or Arguing From Silence

After making his argument that no faithful Jew in the first century would have tolerated the use of images, Rev. Carpenter proceeds to argue that Christian iconoclasm can be proven by the absence of any vocal objections by other Jews. He writes:

Therefore, we can surmise that had the early church immediately adopted the use of icons in their meetings, there would have been vigorous denunciations from the traditional Jews. Given the heated controversy over circumcision and eating ceremonially unclean meat, surely an innovation involving Talmudic Judaism felt so strongly about as imagery in worship would have caused a heated debate that would have left some records (p. 110; emphasis added).

But we read in Abkat Rokel a quite different picture of early Judaism:

Indeed, curtains embroidered with figures are in use in almost every country where the Jews are scattered, without any fear of disturbing the thought of worshipers in the synagogue, for the reason that artistic decoration in honor of the Torah is regarded as appropriate and the worshiper, if disturbed by it, needs not observe the figures, as he can shut his eyes during prayer (Responsa #66, cited in Bigham p. 73; emphasis added).

John Carpenter’s argument reminds me about a Sherlock Holmes’ story about the dog that didn’t bark. It was initially thought that the dog’s failure to bark meant that no one had entered into the stable, but it later turned out that the dog did not bark because the perpetrator of the crime was the dog’s owner. So much for arguing from a silent dog! The point here is that the reason why there was no evidence of a ruckus over icons among first century Jews was because images were already in common use and widely accepted by early Jews.

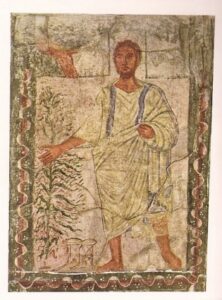

Moses and Burning Bush – Dura Europos. Source

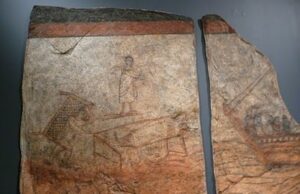

One conspicuous evidence of early Jews being comfortable with the use of images in worship is the Dura-Europos synagogue. Archaeologists found on the walls of the ancient synagogue images of Abraham “sacrificing” Isaac, Moses receiving the Ten Commandments, Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, Ezekiel’s vision etc. I find it very puzzling that Rev. Carpenter knew of the Christian church in Dura-Europos but makes no mention of the synagogue in that same town! He dismisses Dura-Europos as a lone aberration but I would assert that it provides concrete proof of early accounts of images.

Carpenter’s failure to take into account of the Dura-Europos synagogue seriously weakens his article in two major ways. One, the synagogue gives us reason to believe that the introduction of icons was not due to Christian innovators but to Christians imitating their Jewish predecessors. Two, the presence of a Jewish synagogue in Dura-Europos solves the problem of the lack of Jewish brouhaha over the introduction of images. The solution is that there was no written record of a controversy because there was none in the first place. If the images found in the Dura-Europos were an extension of what was done at the Jerusalem Temple then there wouldn’t be any grounds for controversy. Much of the rigorist readings of the Second Commandment were in response to Jewish resentment of Roman rule in first century Palestine.

Steven Bigham in Early Christian Attitudes toward Images (2004) did a survey of early Jewish attitude toward images showing that the use of images was quite extensive among early Jews. (See my third review of Bigham’s book.) Andrew Louth in Greek East and Latin West (2007) noted that the aniconic Jewish synagogue was a later development, not something the early Christians would have been familiar with (p. 43).

Pagan and Early Christian Evidences

John Carpenter used the accusation of atheism by pagans as proof that the early Christians were aniconic. He writes:

Furthermore, early Christians (and sometimes Jews) were commonly called “atheists” by the Romans. They did so because the Christians (and Jews) did not have any images in their homes or churches and hence assumed that they had no gods at all (p. 111).

Using the pagan Romans’ perception of the early Christians to assess what was going on among the Christians is highly problematic. The pagans were outsiders with little or no understanding of the Faith.

Carpenter then cites a Christian source, Origen, but even then there are problems with using Origen to prove early iconoclasm. Origen wrote:

It is in consideration of these and many other such commands, that they [Christians] not only avoid temples, altars, and images, but are ready to suffer death when it is necessary, rather than debase by any such impiety the conception which they have of the Most High God (Contra Celsus 7.64 in Carpenter pp. 112-113).

The main problem is that that the context of this passage has to do with why Christians abstain from participating in pagan worship. There is no reference to how Christians in Origen’s time worshiped. In short, Carpenter mishandled his patristic sources. Carpenter’s unfamiliarity with patristic sources can be seen in his spelling “Origen” as “Origin.”

Eusebius of Caesarea

It is puzzling that Rev. Carpenter overlooked or ignored Eusebius the premiere early church historian. There are at least three passages that challenges Rev. Carpenter’s claim that the early Christians were aniconic or iconoclastic. We read in Eusebius’ Church History:

Nor is it strange that those of the Gentiles who of old, were benefited by our Saviour, should have done such things, since we have learned also that the likenesses of his apostles Paul and Peter, and of Christ himself, are preserved in paintings, the ancients being accustomed, as it is likely, according to a habit of the Gentiles, to pay this kind of honor indiscriminately to those regarded by them as deliverers (Church History 7.18; emphasis added)

It should be noted that Eusebius did not say that these portraits were used in churches. But they had to have been displayed somewhere. One possibility is that they were on display in the privacy of peoples’ home. If one takes into account that it was the wealthy who could afford to order the manufacture of these paintings of Christ and his Apostles and that the large homes owned by the wealthy were often where the Sunday worship services were held then it is not a stretch to hypothesize these portraits were used in the context of Christian worship.

If we link Eusebius’ comment with the archaeological findings of images on the walls of a Jewish synagogue and a Christian church in Dura-Europos then our hypothesis becomes more plausible and even more likely. The evidence does not say how the Christians related to these icons. Did the early Christians kiss them like the way Orthodox Christians do today? The evidence here is insufficient to answer the question. But the evidence does support the reasonableness of our hypothesis that it was not uncommon for Christians to have pictures of Christ and the Apostle on church walls and the untenability of Carpenter’s claim that the early Christians were aniconic.

There are other historical evidences by Eusebius that John Carpenter omits. One is Eusebius’ account of the statue of the healing of the woman with the issue of blood.

Eusebius writes:

For there stands upon an elevated stone, by the gates of her house, a brazen image of a woman kneeling, with her hands stretched out, as if she were praying. Opposite this is another upright image of a man, made of the same material, clothed decently in a double cloak, and extending his hand toward the woman (Church History 7.18, emphasis added).

In another account Eusebius describes in Proof of the Gospel the image of Abraham’s hospitality to the three visitors that could still be seen in his day.

And so it remains for us to own that it is the Word of God who in the preceding passage is regarded as divine: whence the place is even today honored by those who live in the neighborhood as a sacred place in Honor of those who appeared to Abraham, and the terebinth can still be seen there. For they who were entertained by Abraham, as represented in the picture, sit one on each side, and he in the midst surpasses them in Honor (The Proof of the Gospel 4.9 in Bigham pp. 210-211; emphasis added).

The one mention of Eusebius by Rev. Carpenter was Eusebius’ alleged letter to Emperor Constantine’s half-sister, Constantia. In the letter Constantia requests a picture of Christ and in reply he rebuffs her request on the ground that the true image of Christ could not be reduced to mortal flesh.

There are problems with this evidence proffered by Carpenter. One is that the letter is at odds with other writings by Eusebius that had a more positive tone with respect to Christian images. It is disturbing that Carpenter did not take into account the letter being inconsistent with the broader context of Eusebius’ literary career. Even more distressing is Carpenter’s failure to note the dispute among scholars surrounding Eusebius’ Letter to Constantia. Steven Bigham in Early Christian Attitudes toward Images devoted about 12 pages to a detailed discussion (Bigham pp. 193-206). This contrast sharply with Carpenter’s zero pages!

Even more disturbing is the theological argument found in the Letter to Constantia. Carpenter provides the reader with the following quote:

The flesh which He put on for our sake … was mingled with the glory of His divinity so that the mortal part was swallowed up by Life. . . . This was the splendor that Christ revealed in the transfiguration and which cannot be captured in human art. (citation in Carpenter p. 116; emphasis added)

What is disturbing about the theological rationale for Eusebius’ iconoclasm is that it is based upon the heresy of monophysitism: the false teaching that Christ’s divine nature swallowed up his human nature. By citing this letter and its theological rationale, Rev. Carpenter seems to have embraced a Christological heresy that was condemned by the Sixth Ecumenical Council. He should let us know where he stands on theological rationale given in the text above. If he does reject this heresy, then why would he want to use this letter?

Epiphanius of Salamis

Another early witness cited by Rev. Carpenter is Epiphanius, bishop of Salamis. This is an impressive witness because the Orthodox Church recognizes him as a saint. Also striking is the unmistakable iconoclastic language found in Epiphanius’ letter.

Moreover, I have heard that certain persons have this grievance against me: When I accompanied you to the holy place called Bethel, there to join you in celebrating the Collect, after the use of the Church, I came to a villa called Anablatha and, as I was passing, saw a lamp burning there. Asking what place it was, and learning it to be a church, I went in to pray, and found there a curtain hanging on the doors of the said church, dyed and embroidered. It bore an image either of Christ or of one of the saints; I do not rightly remember whose the image was. Seeing this, and being loth that an image of a man should be hung up in Christ’s church contrary to the teaching of the Scriptures, I tore it asunder and advised the custodians of the place to use it as a winding sheet for some poor person. They, however, murmured, and said that if I made up my mind to tear it, it was only fair that I should give them another curtain in its place. As soon as I heard this, I promised that I would give one, and said that I would send it at once. Since then there has been some little delay, due to the fact that I have been seeking a curtain of the best quality to give to them instead of the former one, and thought it right to send to Cyprus for one. I have now sent the best that I could find, and I beg that you will order the presbyter of the place to take the curtain which I have sent from the hands of the Reader, and that you will afterwards give directions that curtains of the other sort— opposed as they are to our religion— shall not be hung up in any church of Christ. A man of your uprightness should be careful to remove an occasion of offense unworthy alike of the Church of Christ and of those Christians who are committed to your charge. (in Jerome Letters 51)

The above paragraph is part of a long letter by Epiphanius to John, Bishop of Jerusalem. The main topic of the letter was Epiphanius’ forcible ordination of Jerome’s brother, Paulinian. The concluding iconoclastic paragraph was an apology or rather an apologia for his removal of curtains with images from a church in Bethel which was under Bishop John’s jurisdiction. One gets the sense that the Bishop of Salamis was like a bull in a china shop leaving havoc and hurt feelings in his wake.

In the debate about icons some have questioned the validity of Epiphanius’ letter. One is the Rev. Steven Bigham who wrote: Epiphanius of Salamis: Doctor of Iconoclasm? Deconstruction of a Myth. Leonid Ouspensky in Theology of the Icon noted that the bishops at the Seventh Ecumenical Council concluded that the iconoclastic letter attributed to Epiphanius were spurious on the grounds that while he was bishop there were churches on Cyprus that had been decorated with paintings (Ouspensky p. 131). Another well known Orthodox theologian, Georges Florovsky, in The Eastern Fathers of the Fourth Century considered the iconoclastic letters spurious (pp. 238-239). At the same time Florovsky noted that other sources considered genuine confirm Epiphanius’ aversion to visual images in church.

On the other hand, Jaroslav Pelikan in The Spirit of Eastern Christendom noted that even in modern times Epiphanius’ letters are still disputed, but he considered the iconoclastic treatises “probably genuine” (p. 102). Johannes Quasten in Patrology Vol. III noted that controversy surrounds the well known Letter 51, but that there are other sources that confirm Epiphanius’ opposition to images. Especially interesting is the letter to Emperor Theodosius I in which Epiphanius complained about his attempt to stop the making of images being ignored by his fellow bishops and mocked by the laity (Quasten p. 392).

Carpenter notes that he could not find any written evidence of an early church leader defending the use of images in church prior to the fifth century (p. 119). One possible reason is that images in church were part of the normal taken-for-granted practice. This is much like the way Protestants take for granted the presence of pews in their sanctuaries. The absence of written apologia for pews does not disprove the presence of pews in Protestant churches. Another possible reason is that Epiphanius’ opposition to images was viewed as a peculiarity and not a significant threat to the church. It was not until the eighth century that images and iconoclasm had become a major issue meriting not only written responses by Theodore the Studite and John of Damascus, but also a conciliar response, Nicea II. Part of the problem lies with Rev. Carpenter’s unrealistic expectations and his apparent unwillingness to work with sparse and ambiguous historical evidences. Another is that he is once again arguing from silence.

In terms of Rev. Carpenter’s fundamental argument that icons were not part of early Christian worship, Epiphanius as a witness is out of place. He was born in 315, just after Christianity became a legal religion, and died in 403, after the first two Ecumenical Councils. He can be viewed as a relatively late witness to iconoclasm, after Constantine. This does nothing to bolster Carpenter’s argument the early (pre-Constantine) Church was either aniconic or iconoclastic, but it does shed light on an important transition then taking place in Christian piety after Christianity became a public faith.

Council of Elvira

Another historical evidence cited by Rev. Carpenter against icons is the Council of Elvira which decreed:

Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not become objects of worship and veneration.

One thing I noticed was that the English translation given by Rev. Carpenter differed slightly from that given by Steven Bigham:

Placuit picturas in ecclesia esse non debere, ne quod colitur et adoratur in parietibus depingatur.

It has seemed good that images should not be in churches so that what is venerated and worshiped not be painted on the walls. (in Bigham p. 161)

There are problems with Rev. Carpenter’s translation of the Latin text. The literal translation of “parietibus depingatur” is “paint the walls” (passive voice). It is not clear where his rendering “placed in churches” come from. Bigham’s more literal translation allows for a more flexible and even ambiguous reading of Canon 36. Carpenter’s translation seems slanted so as to lock one into an iconoclastic reading. With respect to the Council of Elvira’s Canon 36, Steven Bigham notes that we don’t know of the immediate circumstances and that the canon may have been intended as a temporary restriction (Bigham 2004, p. 161 ff.). This problem is not apparent in Carpenter’s discussion of the text. See Gabe Martini’s discussion about the challenge of translating the Council of Elvira.

Good historiography calls for a careful handling of the evidence. In many instances scholars don’t know the immediate circumstance of a particular text or decision so they make educated guesses. In making guesses it is important that they use a tentative tone rather than a dogmatic tone. Carpenter on the other hand makes bold, unqualified statements. He writes:

The prohibition was against any images in the church buildings to forestall the danger of those images becoming icons. Hence, the 19 bishops at the Synod of Elvira were objecting to the presence of art in a church because of the temptation it presented; for example, they would object to our stained glass, saying that it had the potential to become idolatrous (p. 115).

There is so much we don’t know about the Council of Elvira and so little about what prompted Canon 36 that it is amazing to read Carpenter’s bold, audacious conclusion. This kind of bold language is something of a tradition in many Protestant fundamentalist circles, showing up in sermons or Sunday School lesson, but such dogmatism is completely out of place and inappropriate in a scholarly context, especially not in a refereed journal article!

Rev. Carpenter’s citing the Council of Elvira is something of a Protestant tradition that goes back to the Reformer John Calvin. In my article Calvin Versus the Icon I made the following assessment about Calvin’s handling of patristic literature:

However, in dealing with patristic literature it is not enough throw out names and councils as Calvin did. One must show how these references demonstrate a universal consensus among the church Fathers (i.e., Vincent of Lerins’ famous canon: “What has been believed everywhere, always and by all” Quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus). In the field of constitutional law the legal scholar’s strongest argument rests upon the findings of the Supreme Court, not the lower courts. Calvin’s references to one minor bishop (Epiphanius) or one local council (Elvira) or the polemical work sponsored by a king (Libri Carolini by Charlemagne) are all minor league stuff in comparison to the universal authority of an Ecumenical Council (Nicea II) and the reputation of highly respected church Fathers (John of Damascus and Theodore the Studite).

Carpenter’s handling of historical evidences and sources from early church fathers and church councils is much like amateur lawyers attempting to practice law before the Supreme Court. The American legal system consists of a network of hierarchies. We cannot pick and choose court decisions to live by; this will result in judicial anarchy! For Orthodoxy the Seven Ecumenical Councils have settled doctrinal controversies thereby restoring unity to the Church. Having ignored or outright rejected the Ecumenical Councils Protestant Christianity has become a confused cacophony of doctrines and creeds.

III. Assessment and Response

Assessment of Rev. Carpenter’s Argument

Rev. John B. Carpenter’s article fails to achieve its stated goal of repudiating the Orthodox use of icons. Here is a listing of problems I found in his article:

(1) Because he started out with a very flawed and faulty understanding of Orthodox tradition as static, Carpenter ended up constructing a straw man argument. If Rev. Carpenter disagrees with this claim then he must provide serious evidence showing that Orthodoxy understands Apostolic Tradition as static. Instead of simplistic Internet sources, Rev. Carpenter should draw on authoritative sources like an Orthodox hierarch (bishop), an early Church Father, or Ecumenical Council.

(2) His presentation of historical evidence is biased. His failure to include pro-icon accounts by Eusebius and early archaeological evidence suggests that he was not being fair in his consideration of the evidence. His relying solely on rigorist Jewish rabbinical sources and his ignoring moderate sources like Abkat Rokel raises serious questions about his scholarship.

(3) His historiography is amateurish. Unlike most historians who are willing to work with evidences that are sparse and at times ambiguous, Carpenter insists that the pro-icon side present irrefutable written evidence that early Christians venerated icons in the context of their worship services. The discipline of history is quite different from today’s courtroom where in a murder trial the prosecuting side must make an argument beyond a reasonable doubt. There were times when I thought Rev. Carpenter’s reasoning was more like a prosecuting attorney than a careful historian.

(4) His simplistic handling of early Christian sources weakens his argument. The Council of Elvira was an obscure minor council. One sign of a council’s importance is its being cited by others. But in the case of Elvira, it was soon forgotten until cited by the Protestant iconoclasts. It is telling that Elvira was not cited at the 754 iconoclast council. One minor council does not make for consensus of theological opinion. This leads to a related weakness in Carpenter’s approach. He failed to take into account the importance of consensus and conciliarity in the early Church. When a theological controversy surfaced among the early Christians there would be opposing sides. In time a unified consensus would be reached and affirmed by the Church catholic at an Ecumenical Council. For Rev. Carpenter to prefer the 754 iconoclast council over the Seventh Ecumenical Council of 787 shows his independent spirit and his independence from the one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

(5) So what are we to make of the anti-icon evidence presented by Carpenter? I would contend that in light of the broader context of the evidence presented in this posting that we see two things: (1) both early Judaism and early Christianity were quite accepting of images in worship and (2) there was a minority iconoclastic viewpoint among Jews and Christians. The iconoclastic view would come to dominate diaspora Judaism, while among the Christians it would be a minority view until its emergence as a significant movement in eighth century and its subsequent repudiation at the Seventh Ecumenical Council.

We Deserve Better

If there is to be fruitful dialogue between Protestants and Orthodox Christians on the issue of icons, it is important that both sides adhere to high academic standards. I was surprised that the issue of JISCA in which Carpenter’s article appeared did not list the authors’ background and credentials. From what I could find on the Internet, the Rev. Dr. John B. Carpenter is pastor of Covenant Reformed Baptist Church in Caswell County, North Carolina, and earned his Ph.D. at the Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago. Given Rev. Carpenter’s excellent education, it is disheartening that in his introduction he relied on Internet sources rather than the more widely accepted Orthodox authorities like an Orthodox hierarch (bishop), a Church Father, or an Ecumenical Council. As I read through John Carpenter’s article I was disturbed by his failure to interact with Orthodox sources like Jaroslav Pelikan’s Imago Dei and Leonid Ouspensky’s Theology of the Icon. And as noted earlier it is puzzling to find Carpenter leaving out critical evidence not favorable to his side. It is to be hoped that in the future the Rev. Carpenter will give us a more balanced and critically informed argument on icons.

A Challenge

Rev. Carpenter seems to be unfamiliar with the Orthodox understanding of capital “T” Tradition. Icons are indeed an integral part of Orthodox worship, but to say that they are “central” to Orthodox worship is laughable. What is central to the Divine Liturgy are the Gospel reading where we hear the words of Christ and the Eucharist where we receive Christ’s body and blood.

If Pastor Carpenter wishes to challenge Orthodoxy’s claim to unbroken apostolic continuity, he should marshal his arguments against two claims made by the Orthodox Church: (1) its claim to unbroken episcopal succession from the original Apostles to the present day and (2) its teaching of the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist. For Orthodoxy the episcopacy and the Eucharist form the core of Tradition. Icons, on the other hand, acquired dogmatic significance in the later centuries.

The significance of the episcopacy lies in the bishop as the official recipient and guardian of Apostolic Tradition. If Rev. Carpenter wishes to disprove Orthodoxy’s claim to apostolic continuity he needs to show how the early church was either congregational or presbyterian in polity and that the episcopacy was added on at a later date. But to do that he would need to take into account the very early witness to the episcopacy by Ignatius of Antioch who died 98/117.

Unlike Rev. Carpenter’s mistaken assertion that Orthodoxy “makes icons a central part of their liturgy and tradition” (p. 107), it is the Eucharist that is central to Orthodox worship. More specifically, it is the understanding that in the Eucharist we feed on Christ’s body and blood, a teaching that diverges from the memorialist understanding so widespread among Protestants and Evangelicals today. If Rev. Carpenter wishes to disprove Orthodoxy’s claim to apostolic continuity he needs to show how the early church held to a memorialist understanding of the Eucharist.

Robert Arakaki

Thank you so much for the post. I came up in the Presbyterian Church and was firmly entrenched in the Reformed camp, but over the past year of prayer, deep Scripture reading, and finally reading the early Fathers, I have found my own understanding changed out of a deep desire to find historic Christianity.

I only discovered your site recently because of its link from DroptheFilioque.org and I discovered that thanks to the links provided on Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy’s site. Father Damick’s work has educated me greatly over the past year, as has the work of Kallistos Ware, and Vladimir Lossky in addition to Scripture and the Fathers themselves.

Once I would have looked back in an attempt to find the earliest Christians affirming the Protestant Reformation, especially the doctrines of Calvin and Luther. Yet an honest examination does show the Orthodox Church to be the preserver of the faith of the Apostles and the Tradition given to them. That doesn’t mean that there is no flexibility inside of it – as you argue in your first point. Reading the histories, the Tradition is unchanged yet dynamic as well. There is no new revelation, no innovation, yet there is freshness as all times because of Christ’s presence.

I still am seeking an Orthodox Church to attend and experience the Liturgy, but am leaning towards moving in that direction. Yet so many of the things that I once found “weird”, I understand. The theology itself makes so much sense, from the non-Augustinian view of Original Sin, to the essence and energies of God, to even the concept of what icons are and why they are venerated. Above all, the hardest step is towards the Eucharist, but my view has changed on that with careful reading of scripture (I found that learning Attic Greek in college changed so many of my thoughts on scripture).

So thank you again. I’ve shared this with some other Protestant friends of mine as it is such a good response to the common issues people find. It tackles many of the issues I discussed with an old pastor and friend of mine over the summer. He teaches church history, yet has very little knowledge of the Orthodox. As I began to explain to him the concept of venerating the icons, venerating Mary, and praying with the Saints – as the concepts had been explained to me – he began to see the sense of it all too.

We often are blinded by our own perspective and a fear of the different. Eastern Christianity is different from what we’ve known in the West. Less scholastic, more mystical, and the place where the Apostolic Church has endured for nearly two millennia. Jesus stated that the gates of hell would not triumph over His Church – and how could He ever be wrong?

Jeff,

I’m glad you found the blog posting helpful. As regards the Liturgy and the Eucharist, you might find my blog posting: “Platonic Dualism in the Reformed Understanding of the Real Presence?” of interest. I brought up the Liturgy and the Eucharist in other places. You can use the search widget in the upper right corner to help you find these blog postings.

Robert

The “Orthodox” church radically broke away from the early church, as their idolatrous use of icons indicates.

Read my article. This “rebuttal” is dishonest obfuscation.

I’ve read your article and find it flawed. I’ve done historical examinations of the early church (history is, after all, what I was trained in). Images WERE used by both Jews and early Christians. I’ve also worked in the archaeological field in the past, studying under a well known professor of Biblical archaeology who specializes in the first century. While there are no icons as they look now, there are many images that were involved in both first century and earlier Jewish worship. There is a great difference between using something IN worship versus worshipping the image.

You have not done much in the way of refuting any of the facts presented and have not countered the evidence with your own but only called it dishonest. The evidence presented in your original article is far from compelling and was easily refuted.

I’d also like to state that this is not merely about icons. If you are concerned about loyalty to the early church and, importantly, to scripture itself then I must ask, who is your bishop? Scripture clearly lays out a church structure of bishop, priest (presbyter), and deacon. So does your church have a bishop? Was the bishop installed through the laying on of hands in direct line from the Apostles? Even if not, does your church structure conform to scripture? If not, have you not also broken away from the early church?

I do not believe you are capable of producing one example of an icon in the early church. You wrote: “there are many images that were involved in both first century and earlier Jewish worship”. That’s frankly false. If you had any evidence of such images, please present them now. If you cannot, please honestly admit your mistake and retract your statement.

You also said that scripture clearly lays out a polity of bishop-priest-deacon. That too is false. First, the term “bishop” (episcopas) in consistently used synonymously with elder (presbyter, not “priest). See Titus 1. The offices are the same.

John,

Scripture clearly shows a functional difference between bishop and priest. Acts 14:23 and Titus 1:5 show that presbyters are never ordained by their own assemblies but by those authorized to do so (bishops), in EVERY church. Those ordained by the bishops do not also have ordaining authority themselves, but are local priests/pastors.

@Canadian,

Scripture shows no such thing. In fact, it doesn’t even support the existence of the offices of “bishop” and “priest.”

“presbyter” means “elder”, not “priest”. And “episcopos” means “over-seer” not “bishop.” The offices of elder and over-seer are the same. They are used synomously, especially in Titus 1.

Your article simply avoids the real evidence, such as that of Elvira (36), Eusebius, Epiphanius, etc., and engages is spurious reasoning. For example, you claim that the episode when Jesus points to a Roman coin as evidence that Jesus must not have shared Judaisms’ iconoclasm. You fail to note that Jesus had to ask for a coin to be brought to show for the lesson, demonstrating that He had no such coin himself or to note that such Roman coins had to be exchanged outside the temple proper in part because of such images.

Or, you falsely claim that I don’t mention Dura-Europas, I do in fact mention it. I mention it as (1) an exception and (2) an example of decorations that don’t prove they were used for iconography.

Your response is an example of obfuscation.

You’ve had over a year to provide examples of your claim that the early church had icons. You haven’t done so. I don’t believe you can.

Rev. Carpenter,

When I wrote my article I did my best to make it evidence-based and based on careful scholarship. Whether or I not made a convincing case rests not just with you but with the other readers. I intended the OrthodoxBridge to be a forum where Christians from different traditions can engage in a positive and civil dialogue. I may not have persuaded you, but I hope others found my evidence and reasoning persuasive. The challenge for you or your fellow Protestants to give a strong evidence-based argument for iconoclasm. This is needed if the conversation between the Reformed and the Orthodox traditions is to advance.

Robert

@ Robert,

Your article simply avoids the real evidence, such as that of Elvira (36), Eusebius, Epiphanius, etc., and engages is spurious reasoning. For example, you claim that the episode when Jesus points to a Roman coin as evidence that Jesus must not have shared Judaisms’ iconoclasm. You fail to note that Jesus had to ask for a coin to be brought to show for the lesson, demonstrating that He had no such coin himself or to note that such Roman coins had to be exchanged outside the temple proper in part because of such images.

Or, you falsely claim that I don’t mention Dura-Europas, I do in fact mention it. I mention it as (1) an exception and (2) an example of decorations that don’t prove they were used for iconography.

Your response is an example of obfuscation.

Really good read Robert.

I’d be curious to see if Mr. Carpenter will interact with your rebuttal.

Though, I somewhat and maybe unfairly believe that he might not given what a “hit and run” attitude he’s had with this subject on various blog sites.

I learned long ago that it doesn’t matter what I believe, but rather what’s true. I’d rather have the truth no matter how I might dislike it and then find a way to deal and worth with it instead of lying to myself.

Evan,

Thanks! I’m glad you liked my blog posting.

I felt obliged to respond Rev. Carpenter partly because he told me about his article, and also because it’s published in a journal. We need to take seriously attempts by Evangelicals and Reformed Christians to interact with Orthodoxy. I’m hoping for further conversations with Rev. Carpenter. As I noted elsewhere we are in a historic period of dialogue between Orthodoxy and Protestantism. I suspect that the conversation is only getting started and will become more lively in the future.

I like what you said about living life according to truth. But let us keep in mind that truth needs to be accompanied by mercy, charity, and humility. I find Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the need for humility brings much needed balance for my spiritual life.

Robert

I totally agree Robert. I’m ashamed to say that I learned much later the humility part in my life.

It was only after seeing the humility in Saints and Elders that I finally understood that I was no better than anyone. That I’m not some kind of brilliant discoverer of Truth. Rather God brought the Truth to me and I responded to it. And my responsibility as one who’s trying to be a Christian is to Tradition that news.

Only after 6 years of my journey, do I see how important the words of Saint Paul are in 1 Corinthians 15:3 “For I delivered to you, first of all, what I also received…”

amen & evan! raised so-baptist, then a military & college navigator disciple, & 33+ yrs reformed/presby elder…the beauties of Orthodoxy are yet a gift…to be humble received as a special mercy. thanks for saying this so well.

I find no humility whatsoever in “Orthodoxy”. They assert their self-serving “history” contrary to the real facts of history, claiming that they have an “unbroken continuity with the early church” when in reality they radically broke away from it, as their embrace of icons shows.

John,

Would you then assert that the Protestant Reformed Baptist denomination most resembles the practices and theology of the early church? This seems to be implicit, but I just thought I would ask.

At what point do you believe the early church was corrupted? Which Ecumenical councils (if any) do you see as authoritative?

Justin

As we try to follow the Word of God. The problem with the “Orthodox” is that they think their organization, ipso facto, is the pure church. But an honest examination of what the early church taught about icons reveals how far the “Orthodox” have strayed.

John,

I understand.

Are paedobaptist Presbyterians following the word of God? Would they say that they are? They claim (ala 1647 Westminster) that by failing to baptize their children, Baptists are guilty of “a grave sin.”

Who is right?

John, where is the Church that Christ promised to preserve?

John,

FWIW, since exploring Orthodox spirituality, I have been driven to new depths of humility. I have found tears of repentance and a level of sorrow and mourning over my sin that I never thought possible before.

So, while you perhaps have not found humility in Orthodoxy, I can say quite definitely that I have found it in heaps.

It’s there. Keep looking.

Justin

You can’t claim to be “humble” while bowing before an “icon” (which is really an idol) and thus breaking God’s command (Ex. 20:4ff) for the sake of your tradition (Mt. 15:6).

I did not say that I was humble, John.

I said that I had been driven to new depths of humility. The distinction is important, and I would ask that you not put words into my mouth.

Your characterization of icons as “idols,” while understood (I came from a Covenanter background, so believe me, I understand), is mistaken.

Would you care to define “tradition” for me, and tell me if you distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate tradition? Would you also tell me if you own any photographs?

John Carpenter,

You said:

“You can’t claim to be “humble” while bowing before an “icon” (which is really an idol) and thus breaking God’s command (Ex. 20:4ff)”

Ps. 5:7, 99:5, 132:7 The Jews are commanded to worship toward the temple and at his footstool. The temple is an object with images for communion with God. And what is the footstool of the Lord? The ark of the covenant in the house of God, 1 Chronicles 28:2.

The hebrew word for worship in these passages is Strongs 7812: prostrate, bow, fall down.

The same word used in Exodus 20, which you cite. The command is not against the act of 7812, which is commanded in the Psalms above and seen also in 1 Chronicles 16:29 where that chapter is describing the “worship” before the ark which has the images of cherubim. So we have commanded bowing before images yet God commands this act NOT be done before false gods. Exodus 20 does not help you.

Perhaps, instead of making personal attacks on the Orthodox in general, you could interact with Robert’s interaction with the article?

As an aside, I have found humility in many Christians of many stripes, Catholic, Orthodox or Protestantism. In no way would I (or could I) make sweeping statements about the lack of humility in any Christian group. Seems a bit unfair and puts me in God’s position, knowing the heart of folks and all that.

John

I didn’t make any personal attacks. Your accusation itself is a personal attack and false at that. I simply said that one cannot claim to be humble before God while disobeying His command; that includes His command not to use images.

Off topic here Robert-

Have you written anything on the medical/Orthodox vs judicial/Protestant concepts of “salvation?”

Coming to better understand the Orthodox understanding of salvation was a turning point for me.

Justin

Justin,

Thanks for asking.

About a year ago I did a two part series in response to Spencer Boersma’s “The Impotence of Calvinism?” The first posting was titled: “The Power of God’s Mercy” and the second “The Orthodox Priest Toolbox for Pastoral Care.” Hope this helps.

Robert

Thanks Robert!

Hey Robert,

Thank you for this, both this article and your site. Your analysis and citations have been extremely stabilizing as I’ve been on my search for the True Faith. Just baptized and chrismated last week and am fully appreciative of the online intellectual resources discussing Orthodoxy and comparing it with other faiths. I fully agree that this time is extremely important in the dialogue between East and West, and we should definitely be taking it seriously. Thanks for that reminder. Please keep it up.

Best,

Becca

Becca,

Congratulations! I’m happy to hear of your becoming Orthodox.

And thank you for your appreciation of the OrthodoxBridge. I want it to be helpful to people inquiring into Orthodoxy. I also want to point out that this blog is very dependent on the outreach of local Orthodox parishes. It is in the local parish where we join in the liturgy and meet real flesh and blood Orthodox Christians that we find out what Orthodoxy is all about. Just one friendly smile, a handshake, and going up to someone saying: “I’m glad you’re here with us!” can make all the difference in a person’s journey to Orthodoxy.

Robert

I went to my second Liturgy yesterday.

The first one was overwhelming. Sensory overload. Foreign. It left an alien -but not bad- taste in my mouth.

So I bugged a bunch of people, spoke with the priest a few times on the phone and picked some brains, and started to read, read, read. What is all this about? I began to learn.

So I made the two hour drive and went back yesterday.

This second one was worship. Overwhelming. Ancient? Powerful. Words fail me. What can I say?

I believe I am home.

Great to hear about your experience with the Liturgy!

Robert

Sorry I’m so late in the discussion. I’m new to the Study of Orthodoxy and this web site. I’m glad I found it.

I read your early experience in visiting your 1st and 2nd Liturgy. I must say it’s exactly what I experienced!

I’m glad you found the Liturgy uplifting. That’s a great way to begin one’s journey to Orthodoxy!

Becca,

Robert’s site had somewhat of a 2×4-upside-the-head effect on me. 🙂 I too am appreciative of his site and efforts.

Congratulations on your Baptism/Chrismation!

Justin

God be praised Justin…Becca! Right there with you.

This reply simply obfuscates in typical “Orthodox” fashion.

1. A religious tradition that bases it’s legitimacy on an unbroken continuity to the early church (in their own words) can’t defend it’s contradictions from the early church by claiming they are dynamic. The quote you provide from Bingham underlines this. He says that the tradition can’t be corrupted. Since the tradition of the early church was clearly to exclude icons, then we have to conclude that the “Orthodox” church has broken with the true church.

There are no icons in the Old Testament. I didn’t deal with that because it’s not a church history discussion but the Old Testament prohibits the use of images for worship (in the second commandment, Ex. 20:4ff). The decorations of the temple were not icons as they were not used in worship.

See my article for a discussion of a proper definition of “icon”. The author of this response consistently tries to conflate “images” with “icons” in order to imply that any occurrence of an image is an example of an icon. I refuted this in my article.

2. My presentation of historical evidence is universal. I excluded no mention of “icons” that I am aware of. If the author has examples of “pro-icon accounts by Eusebius” then he should present them.

3. Requiring “irrefutable written evidence that early Christians venerated icons in the context of their worship services” isn’t being “amateurish” but being historically rigorous. Most likely, the author is so accustomed to “Orthodox” historians who must rely on “sparse and at times ambiguous” implications. They have to do that because that is all that they have. They don’t have concrete evidence of what they claim and so it’s not my history that is “amateurish” but theirs that is propagandistic.

4. My citing early church sources is not a “simplistic handling of early Christian sources”. It’s what church historians do. I quoted every mention of icons in the early church that I could find, after consulting “Orthodox” sources and repeatedly challenging “Orthodox” apologists to present their case. The Council of Elvira is likely the most significant council in from Jerusalem (in Acts) until Nicaea (325). It is representative of the opinions held in the Iberian peninsula and therefore likely of the whole church at that time.

5. The author concludes, “both early Judaism and early Christianity were quite accepting of images in worship”. There is no evidence for this whatsoever. All of the evidence from the early church shows the opposite: that they condemned images in worship.

5. The author concludes, “both early Judaism and early Christianity were quite accepting of images in worship”. There is no evidence for this whatsoever. All of the evidence from the early church shows the opposite: that they condemned images in worship.

Except for the evidence Robert presented in his post?

He didn’t present any evidence. He did the usual inferences and assumptions while ignoring the clear statements on the issue from Origin, Elvira, Eusebius, Epiphanius, etc.

John Carpenter,

Your points one-by-one:

1) You assume your conclusion in arguing that there is corruption in the tradition. The point is that you have to prove your conclusion first.

2) You seem to be ignoring Robert’s points, and assume that just citing all instances of “icon” is a sufficient argument.

3) “Requiring irrefutable written evidence” is amateurish when it means ignoring other factors. Something can be established without a direct statment of one’s conclusion. That is often what historical research is about.

4) I understand that you feel your article is being attacked, but Robert has a point in saying that your handling of the evidence is simplistic. He brings some important evidence to view . . . particularly with regard to Elvira.

5) It is unclear what “in worship means.” I think that it is unclear that images were used in worship as the Orthodox venerate them now. However, the existence of images in places of worship has been fairly well demonstrated both for Judaism and Christianity.

Coming to historical conclusions without explicit written evidence stating the conclusion is not rigorous, it just excludes other kinds of direct evidence as well as implications of written evidence. A rigorous position would admit where the evidence is weak as well as where it is strong. I think that in any version of Christianity one will have to move from evidence to faith at some point. While Orthodoxy has its own challenges historically, apologetics is not meant to prove a position, it only needs to show that ones position is plausible. I think that Robert succeeded in showing that images in a worship setting were commonplace in 1st century Judaism and Christianity. Whether they were used in worship the way the Orthodox use them now is another question altogether (i.e. veneration). The historical evidence of the first three centuries of Christianity is rather spotty. One’s understanding of the nature of Christianity rests on how one interprets the documentary data from Judaism, the early Christian documents, as well as how well one assumes the 4th century church matches that of the 1st century. One piece of evidence that I didn’t see discussed is the fact that the Oriental Orthodox venerate icons, even though they went out of communion with the Eastern Orthodox over the Chalcedonian definition of Christology (the miaphysite issue). This suggests that the tradition of veneration of icons is venerable.

Prometheus,

From time to time I visit a nearby Coptic Church. These visits are very educational and eye opening. It’s fascinating to see where they are alike and where they differ from the Byzantine Orthodox. They use the Liturgy of St. Basil which is older than the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom which is what the Orthodox normally use. The Orthodox use St. Basil’s Liturgy about 10 times a year.

I also found that the Coptic Church has icons. St. Mark Coptic Church in Honolulu, Hawaii has four large icon panels of the life of Christ from his birth, his childhood, his crucifixion, and his ascension. I recently walked right up to the icon and discovered that the icons were painted on the wall! This is contrary to what we read in the Council of Elvira!

Your comment about the veneration of icons touches on a very important issue, one that I hope to address in a future blog posting.

Thanks for contributing to the conversation on the OrthodoxBridge!

Robert

I proved my conclusion in the original article. I suggest you read it. The early church strictly prohibited icons. That’s the verdict of history.

Replying to your points as enumerated:

1. Your statement is simply false. In the article I document the stance of the early church with Eliva (36), Origin, Epiphanius, Eusebius, etc. The conclusion from that primary source evidence is that the early church prohibited icons. Then we have to conclude that the “Orthodox” church has broken with the Apostolic Tradition.

See my article for a discussion of a proper definition of “icon”.

2. My presentation of historical evidence is universal. I excluded no mention of “icons” that I am aware of. Robert’s response consistently tries to conflate “images” with “icons” in order to imply that any occurrence of an image is an example of an icon. I refuted this in my article.

Further, Robert didn’t present any evidence. Historical evidence is either material (like archaeological), empirical or documented (such as actual quotes from primary sources). Robert presents none of this. Instead he deals in inferences and assumptions while ignoring the clear statements on the issue from Origin, Elvira, Eusebius, Epiphanius, etc.

3. Requiring “irrefutable written evidence that early Christians venerated icons in the context of their worship services” isn’t being “amateurish” but being historically rigorous. It’s what history is. Your statement appears to be attempting to redefine the whole discipline of history in order to suit the agenda of proving a thesis that cannot be proven: the “Orthodox” thesis that their worship preserves the pattern of the early church.

4. Presenting primary sources is what church historians do. I quoted every mention of icons in the early church that I could find. I note, that you don’t say exactly what FACTS Robert has presented that disprove the primary sources I’ve mustered. You just assert that he has.

The Council of Elvira is considered an official “council” (not simply a Synod) of the Catholic Church and was one of three councils that approached the character of a general council, preparing for the first ecumenical council.

5. What is clear is that the Orthodox use images in worship now and that they could not in the early church.

Robert presented no evidence whatsoever that images were accepted in the early church. All the primary sources say the opposite.

That said, I think your actual article has some good non-textual as well as textual evidence – as well as a good distinction between art and icon. I’ll have to think through it some more.

I would like to submit that certain Protestant traditions have even weaker evidence than that of Orthodox iconography. The early church not only did not, but could not have a doctrine such as “sola scriptura,” since the gospel as preached by the church didn’t exist in written form at the beginning. The moment one affirms the completeness and sufficiency of the Bible (whatever books that happens to include) a whole host of questions arise as to its origin and collection – ones that require extra-biblical doctrine to solve (e.g. sola scriptura is a non-biblical doctrine).

The apostolic church had a high view of evangelical usefulness of the Old Testament and having given us the New Testament, we have a complete canon by the end of the 1st century.

Assertion (or denial) is not evidence, Pastor Carpenter. A few of us can see the difference.

Honestly, I find your assertions about the use of images in the OT Tabernacle and Temple laughable. How on earth, when images are contained within the very worship structure and visible to the worshippers, can we say they are not being “used” somehow in worship? The Jewish Temple was the most important site of Jewish worship and the only site where sacrifice to the Lord was permitted. Everything within it, all the vessels used for sacrifice and other aspects of their liturgy were considered sacred–they were sprinkled with the blood of the sacrifices, and set apart for sacred use and could not be profaned by being used for common everyday things. The Jews bowed in veneration toward the Temple in their prayers (and to this day bow toward the Temple Mount in Jerusalem–remember the “wailing wall”?) because it (and everything it contained) was/is the site and symbol of God’s presence and activity in their midst. To this day pious Jews also bow toward and kiss the sacred scrolls containing their Scriptures in their synagogues to reflect their reverence for God and His Word. Orthodox Christians do the exact same thing with the Holy Icons which depict saving events in history and the heroes of the faith, with the Cross, and with the Gospel book on the Altar in an Orthodox temple. When one has an opportunity to observe these practices within their own contexts, it becomes very clear the practices of Orthodox Christians reflect a continuity with these ancient Jewish practices (which also continue to this day) and are an expression of reverence toward God and proper honor of those He has redeemed, and that they have nothing whatsoever to do with the idol worship condemned in the Scriptures.

Shame on you, Pastor Carpenter, for stubbornly perpetrating slander and lies against the Orthodox! There are none so blind as those who will not see. As for the issue of humility, I make no great claims for myself, but I do see it in abundance in those the Orthodox deem Saints and holy elders. As one who struggles with pride, I do know one thing from experience–people full of pride are the speediest at “spotting” it in others and the quickest to make this accusation against others. The faults we “see” in others are most often a mirror image of our own to which we are blind.

With respect, it looks rather obvious to me, Rev. Carpenter, that you are blinded by bigotry and a prior commitment to another position (which theological commitment likely probably also puts a roof over your head and food on your table since you are a Pastor, so you would have good reasons not to want to see your position undermined).

Seeing that you begin with a serious error in fact — that the images in the holy place were visible to the worshippers — the rest of your conclusions are false. The holy place was only visited by the priests. The worshippers were out-side. They were bound by the guidance of the second commandment (Ex. 20:4) telling them not to use any images in worship. God did not give them that command and them tempt them to do otherwise by making the images accessible to them.

You’re ignoring the fact that images of the Cherubim were also woven into the fabric of the curtains that made up the very walls of the whole Tabernacle (Exodus 26:1) and on many of the objects in Solomon’s Temple, such as the doors to the various entrances that were most definitely visible to the worshippers (1 Kings 6:31-35). This also ignores the fact that the Ark of the Covenant was at various times exposed to the whole community of Israel and that they knew what it looked like and what it contained, whether they could actually see it during worship in the Tabernacle/Temple, or not. My case rests.

As in the original article, decorations are not icons. The attempt to conflate the two is obfuscating in order to cover up the lack of icons in the Bible.

Exodus 26:1 does not say the decorations were facing out toward the people.

1 Kings 6:31-35 is about the door to the “inner sanctuary” which appears to be the same same thing as the “holy of holies”. Only priests could get into see the door to the inner sanctuary.

The Ark of the Covenant was very rarely exposed to public view and was never the focus of legitimate worship.

Why were the Tabernacle and the Temple decorated with images of cherubim specifically? It certainly wasn’t just for “decoration” if by that we mean ornamentation to beautify the space–flowers and fruit alone or abstract designs would have sufficed for that. This was certainly something more than mere “decoration” in that sense.

We have established that the images of cherubim could be seen at least by the priests and certainly the high priest. If we accept in the passage in 1 Kings 6 that the door to the “sanctuary” and the door to the “inner sanctuary” are two different doors, we know the door to the “inner sanctuary” logically must have led from the sanctuary, so isn’t it logical to assume the door to the sanctuary led from outside of the sanctuary and could be seen from outside the sanctuary? Even if we could somehow deny that, I think it is splitting hairs at this point not to acknowledge that the prohibition in Exodus 20:4 had to do with images of idols (false gods) and images specifically prohibited by God (i.e. the attempt to depict the invisible God) and was not an absolute prohibition against any and all imagery whatsoever for use in the worship of Yahweh.

Now, I’m certainly not arguing that the priests or people of Israel worshipped these images, and neither do Orthodox worship the Holy Icons. There is no question, though, that they made use of these images depicting heavenly realities, of a particular physical location (the Temple), of the various vessels, and other material objects in their worship and that it was forbidden to treat these physical objects as ordinary things and to profane them. In other words these objects were being honored as set apart to God (holy). By definition, the people’s obedience to treat them with respect as sacred is veneration (regardless of exactly how it is expressed). Further, the Jewish people did bow toward (venerate) the Temple (and by extension all that it contained) as an expression of worship of the true God (Psalm 138:2)–in fact, this is commanded in Psalm 5:7, and this is exactly analogous to what Orthodox do with the Holy Icons and the physical worship spaces set apart for their worship.

I’m certainly not an expert on the Scriptures, but this much at least seems quite clear. In any case, I think we would be hard pressed to deny that St. John of Damascus and others who defended the use of Icons in the Church did not know the Scriptures and understand them in considerable depth.

This is a very curious selected ignorance of some facts very clearly spelled out in the very Scriptures you claim as the sole basis for your faith, Rev. Carpenter. This is a further demonstration that the filters and biases through which we view the inspired Holy Scriptures are as important as what those Scriptures actually say for giving us an accurate understanding and interpretation of their message.

In light of the above, you apparently don’t know the Bible very well.

Karen,

“All lies in jest, still a man hear what he wants to hear and disregards the rest.”

Is a line from an old Simon & Garfunkel song (The Boxer) comes to mind. Lord have mercy.

Ultimately, of course the Orthodox view of Icons does not rest merely upon the abundance of symbols visible in the Tabernacle or Temple — but upon the Incarnation of the eternal Logos, God the Word becoming flesh in the womb of the Virgin Mary. It changed all Creation and Humanity…God becoming Man, visible in the flesh. Thus, the Father’s rightly and most carefully reasoned to the right use of Icons. Only the Holy Spirit can make a man see what he does not wanna see.

Dear Rev. Carpenter,

I was perplexed and disappointed by your response to my review of your article. I was hoping that you and I would have a vigorous discussion about the evidences I presented in my blog posting: (1) Jewish sources like Abodah Zarah 33 and Abkat Rokel which spoke favorably of images in Jewish worship, (2) the implications of the images at the Dura Europos synagogue, and (3) Eusebius’ Church History 7.18 and Eusebius’ Proof of the Gospel 4.9. Nowhere in your response did you engage these specific evidences; this is what I find most disappointing about your response.

I was perplexed in reading your fourth point where you claim that I accused you of “simplistic handling of early Christian sources” because you cited early church sources. My problem was not with your citing early Christian sources (even I do that!). Rather, my problem was your failing to take into account the importance of consensus and conciliarity in the early Church. It seems that you misread what I wrote in my blog posting.

I urge you to reread my review of your article slowly and carefully. If I came down hard on parts of your article, it is because I believe the evidence merits such a harsh judgment. In scholarly matters it is not so much a matter of like versus dislike but the the evidence before us and how we work with the evidence. Believe me; even I have felt the pain of a reviewer sharply criticizing the reasoning of my papers!

I know that you and I have different views about the legitimacy of icons in the early Church, but I do hope that we can have a discussion on the historical evidence before us and on the basis of that evidence assess the soundness of our theological positions.

Lastly, I wished that you had referred to me by name rather than the impersonal reference: “the author.” As Christians we should treat each other with respect and charity, especially when engaged in public debate. Please keep in mind that you are representing the Reformed tradition. This dialogue between the Reformed and Orthodox is a very important one. If you find it difficult to deal with the evidences I presented, you are more than welcome to invite other Protestants to represent your position. In this Reformed-Orthodox conversation we need to hear from the best on both sides.

Robert

Evan,

I unapproved your comment because it crossed the line. Let’s confine our comments to the content of what Rev. Carpenter wrote. You are welcome to reword and resubmit your comment.

Folks, let us keep in mind that personal attacks, even implied, are strongly discouraged on this site.

Robert

No worries at all Robert.

forgive me if i crossed a line brother 🙂

Last thing I would want to do is bring polemics into an exchange and now that I think about it, I do see how my wording made it seem polemical. If you hadn’t deleted it, I’m sure I would have requested it to as soon as I would have noticed with a more sober mind.

Looking forward to see where all this goes and what replies Mr Carpenter will have.

Evan,

I’m glad you understand.

I see this conversation as being bigger than me and Rev. Carpenter. I believe that it’s a historic moment of encounter between the Reformed and the Orthodox traditions. This did not happen in the 1500s during Calvin’s time but is happening now. We need to get the best of Evangelical and Reformed scholars to engage the issue of icons and the Orthodox Tradition. I’m hoping to hear from other Protestant leaders, whether pastor or seminary professor. I’m very conscious of the fact that I represent the Orthodox perspective. That is why I put a lot of time into ensuring that my blog postings are academically sound and make a positive contribution to interfaith dialogue. There’s much that the Orthodox and the Reformed can learn from each other.

Robert

Robert,

My article is comprehensive and you’ve provided no further evidence for icons. I dealt with the Jewish back-ground, Dura Europas and Eusebius in my article. I’d suggest you go back and read it. A rare finding of decorations do not in any way prove iconography.

What you’re trying to do is obfuscate the issue which is really very straightforward. In history, primary sources and direct, unambiguous discussions are king. In the early church, all of the primary sources which speak directly to the issue of images in worship are stark and emphatic in their prohibition of icons, to the point of being more wary of even mere decorations in church buildings lest they become the kinds of idolatry that the early church was trying to set itself apart from.

What you want to do, on the other hand, is infer and assume to get the result that happens to suit the agenda of your pre-existent faith commitment. That’s simply not sound historiography.

In conclusion, you haven’t presented any evidence for icons in the early church.

In examining your article falsely attacking Orthodox icons and iconography, you (mis)quote the meaning of my former Priest’s wife (matushka) on our parish website in Victoria BC, Canada: you conveniently leave out the rest of her sentence, which she gave at a university lecture/workshop! Jenny Hainsworth said,

“Contrary to popular, non-Orthodox belief, icons are not Art, AND SO ARE NOT TO BE JUDGED BY THE CONVENTIONAL RULES OF ARTISTIC EXPRESSION.”

http://www.allsaintsofalaska.ca/index.php/the-orthodox-church/65-about-icons

Clearly, the context of her saying “iconography is not art” is SOLELY in relation to how art is typically analysed and studied from a western perspective (she was giving a university lecture)! She is not saying that iconography isn’t art in any sense! This is important because you’re playing games by claiming that early Christian religious art isn’t “iconography” because – you nakedly assert – it wasn’t “venerated”. Also, elsewhere in the article, Jenny does point out that icons are an art:

“She (Jenny) pointed out that…They can and sometimes do find personal expression in other forms of ART.”

Also, I know Jenny personally and can say that you are abusing her statement for your own ends: hence, why you left out the last portion of the sentence! Why am I making a big deal about this? Because, you want to make the naked assertion that icons (images) are to be defined in the most “idiotic” (in the Greek sense “private”) way: that is to say a definition/opinion held only by yourself.

You wrote,

“That being the case then, the discovery of early Christian art does not mean the discovery of early Christian iconography. By “icons” I am specifically referring to religious symbols to which respect is paid in congregational worship.”

Your flawed private definition intentionally “stacks the deck” in your favour since “icon” – in your narrow definition – must necessarily include 1) veneration and 2) that this veneration be “congregational” to be an “icon” (image). This is a red-herring. The fact that some protestants I know (and one Sikh) – have icons as religious “art” in their homes (but never venerate them) is evidence enough of the absurdity of your assertion. Obviously, these objects in peoples’ homes are still considered to be “icons” regardless of veneration! In no way is “iconography” contingent on veneration to be considered as such! Thus, early Christian art all counts as “iconography”. Whether it was venerated or not is another issue – although it has always been proper for Orthodox Catholic Christians to do so!

Moreover, Orthodox have always considered the Cross, the Scriptures, et cetera also to be “icons”. Also, humans are icons of God because we all bear the divine image (icon), which Christ restored from its fallen state in his incarnation. This is why we venerate each other with the “holy kiss”, prostrations, and the clergy venerate us with the censer and incense! So this again, evidences the “idiocy” (private nature) of your red-herring smeared “definition”, with which no Orthodox would agree.

You wrote,

// A rare finding of decorations do not in any way prove iconography. //

In reality, every ancient church discovered by archeology – without exception – has iconic decorations! So, your statement is false in implying that decorations were rare.

Hi,

1. You’re right that I should have ended the quote (at footnote 10) with an ellipsis, indicating that the sentence in the original continued. However, I see no reason to include the rest of the sentence as it does not change the meaning of the quote. My article is not about the artistic value of icons but about iconography.

2. Orthodox will typically say that icons are not “art”, meaning that they aren’t merely decorations but objects of worship (i.e. “veneration”). As art, I think they are frequently of great value. But to be counted as “icons” they must be objects of worship.

3. An image is an “icon” if it is used for worship. If you have a Protestant friend who likes “icons” for art, then to him such images are not icons but art.

4. Orthodox frequently engage in double-talk when it comes to icons: they aren’t “art” when it suits them and they are “art” when it suits them. They find decorations in a church in Dura-Europas and claim they are “icons” because, apparently, all art are icons. But an image is not an icon if it is not used in worship. To establish that an image is an “icon” you must demonstrate that it was used in worship.

5. You falsely claim that my claim that that there is no evidence for veneration of “icons” in the early church is “naked” (without historical substantiation). This completely ignores the first part of the article. We KNOW that the Jews from whom early Christians came prohibited images; we know Christians were accused of being “atheists” for their lack of images; we have Canon 36 of the Council of Elvira, Eusebius, Epiphanius, etc. We know there was no iconography in the early church.

6. Your statement that it has “always been proper for Orthodox Catholic Christians to” venerate icons flies in the face of ALL the historical evidence.

7. Your statement “every ancient church discovered by archeology [sic] – without exception – has iconic decorations” is false.

Rev. Carpenter,

Good apologetics is based on evidence-based arguments, not dogmatic assertions. The lack of counter-evidence in your comment gives me no basis for a reply.