Gavin Ortlund – Truth Unites

Recently, there have been intense debates between Protestants and Orthodox over icons. Gavin Ortlund, senior pastor of First Baptist Church of Ojai, California, has been a very vocal advocate for the Protestant position on icons. In early December 2022, he uploaded a lengthy podcast “Icon Veneration is CLEARLY an Accretion!” [1:14:54]. Then on 20 January 2023, Pastor Ortlund uploaded “Icon Veneration in the Early Church? Response to Craig Truglia” [42:06]. (The bulk of this article will be in response to the first podcast unless noted otherwise.) Ortlund argues that icons are not a part of early Christianity but a later development or in his words an “accretion.” The argument that icons are an accretion has significant implications: (1) it implies that icons being an innovation contradict Orthodoxy’s claim to have kept the Faith unchanged; and (2) it suggests that the veneration of icons is the result of a reversion to pagan forms of worship.

We have much to be grateful for Pastor Ortlund joining the Protestant-Orthodox dialogue. Gavin Ortlund, has a Ph.D. in historical theology from Fuller Theological Seminary, which makes him well-qualified to represent the Protestant side. Unlike many apologists who have a sketchy understanding of church history, Gavin Ortlund has elevated the conversation with his careful scholarship, his knowledge of church history, and the irenic tone with which he engages the Orthodox and Roman Catholics.

In this article I will present evidence that address Pastor Ortlund’s concerns about the validity of icons. This article will discuss: (1) the historical evidence for early Christian veneration of icons, (2) the strength of the evidence presented, (3) Ortlund’s claim that the veneration of icons represents a regression to Greco-Roman pagan worship, (4) the development of doctrine and church history paradigms, and (5) biblical evidence that support the veneration of icons.

This blog posting is quite lengthy and covers considerable ground. This was necessitated by the wide-ranging and extensive critique of icons by Gavin Ortlund. The primary motive here is not so much to rebut Gavin Ortlund, but rather to enable Protestant inquirers to make the transition to Orthodoxy with a clear conscience and with intellectual integrity.

Gavin Ortlund’s Historical Argument Against Icons

In “Icon Veneration is CLEARLY an Accretion!”—18:50 to 56:19—Gavin Ortlund presents a three-stage narrative of the emergence of icons in the early Church. In the first stage, from the time of the Apostles to the Council of Nicea (325), Christians were actively opposed to the cultic use of images and statues. This opposition set the Christians apart from religious practices of Greco-Roman society (21:51). Pastor Ortlund concludes the first section noting the Ante-Nicene Church was “resounding” and “unanimous” in their opposition to images (30:41-31:40).

Then in the second stage, from the First Council of Nicea (325) to the Second Council of Nicea (787), Christianity undergoes massive changes. It is now a legal religion. Many church buildings are acquired and embellished with works of art. At the 33:06 mark, Ortlund describes the flood of former pagans entering the church bringing with them the habits and practices of their former paganism. At first, they acquired pictures of Christ and the Apostles, then they bowed down to these images in a manner much like their pre-Christian days. At this point for Ortlund, the cultic use of images has begun to surface in the Church and over time would become widespread precipitating the fierce iconoclast controversies of the seventh and eighth centuries.

The third period spans the seventh to twelfth centuries (600s to 1100s). From 600 onward, icons and icon veneration became widespread leading to the iconoclastic reaction. This controversy led to the various pro-icon and anti-icon councils: the anti-icon Council of Hieria (754), the pro-icon Council of Nicea II (787), and the pro-icon Council of Constantinople (843). While the Council of Nicea II (787) settled the matter in the East, in the West there continued to be resistance to the findings of Nicea II, e.g., Council of Frankfurt (794). Ortlund notes that even as late as the twelfth century there were reservations about Nicea II in Western Europe (55:28-56:15).

In this narrative Pastor Ortlund is articulating Protestantism’s Fall of the Church paradigm—the early Church began in simplicity and purity of faith, but then under Emperor Constantine became an institutionalized, corrupted, and worldly religion. Key to the Protestant paradigm of church history is the discontinuity in faith and practice which necessitates the repudiation of later accretions and a return to the purity of early Christianity. In addition to the historical argument, Pastor Ortlund is also making a theological argument—that the veneration of icons violates the Second Commandment. In many ways, Ortlund has made the veneration of icons the “hill to die on.” (In the context of his attempt to promote irenic ecumenism, the phrase “hill to die on” seems to be Ortlund’s way of speaking about theological matters on which there can be no grounds for mediating compromise, but rather unyielding opposition.) Icons represent the watershed divide between Protestantism and Orthodoxy. There is no middle ground on this issue. Thus, the present Protestant-Orthodox debate about icons and icon veneration is far from trivial and involves issues touching on the fundamentals of the Christian Faith.

The Year 600

For Gavin Ortlund, the year 600 serves as a point of demarcation. He mentions this specific date in his response to Frank Bilotto in the comment section. In using 600 as the cut-off point, Ortlund claims he is reflecting the scholarly consensus (see 42:17, 44:40, and 45:24). He argues that if icon veneration is a late practice, it cannot be part of the ancient apostolic practice and therefore must be an add-on or as he puts it: “an accretion.” Here Pastor Ortlund is using Orthodoxy’s claim to an unchanging Tradition against one of its key practices, icons. Therefore, if it can be shown that Christians were venerating images earlier than 600 then Gavin Ortlund’s argument from history is significantly weakened.

Full-Fledged Icon Veneration in 380s

Icon – Theodore the Recruit

One such evidence is Gregory of Nyssa’s “Panegyric to Theodore the Recruit.” Saint Gregory (c. 335 to c. 390) is a Church Father venerated as a saint by Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Lutherans, and Anglicans. In 386, he delivered an oration dedicated to Theodore the Tyro (Recruit), a Roman soldier who was martyred in 306 because of his refusal to obey Emperor Galerius’ order to sacrifice to the idols. His martyrdom was held in high regard by the early Christians. Patriarch Nektarios of Constantinople (381-397) ordered that Theodore’s martyrdom be celebrated on the first Saturday of Great Lent with the distribution of kolyva (boiled wheat sweetened with honey) (OCA.org).

Kolyva – Boiled wheat offered in memory of the departed

The practice of offering kolyva in honor of a departed saint continues to be observed among the Greek Orthodox. My local Greek parish observes this practice. So, for me this little historical detail is not an oddity from the remote past but rather a living tradition with deep historical roots. I used to think that the kolyva was a quaint ethnic custom, but now I am keenly aware that this is a custom that links me to an early martyr and one of the great Cappadocian Fathers.

There are two significant aspects of Gregory’s oration: (1) it dates to the fourth century and (2) its description of fourth century devotional practices bears a strong resemblance to present-day Orthodoxy.

In his oration, Gregory tells his listeners:

Should a person come to a place similar to our assembly today where the memory of the just and the rest of the saints is present, first consider this house’s great dignity to which souls are lead. God’s temple is brightly adorned with magnificence and is embellished with decorations, pictures of animals which masons have fashioned with delicate silver figures. It exhibits images of flowers made in the likeness of the martyr’s virtues, his struggles, sufferings, the various savage actions of tyrants, assaults, that fiery furnace, the athlete’s blessed consummation and the human form of Christ presiding over all these events. They are like a book skillfully interpreting by means of colors which express the martyr’s struggles and glorify the temple with resplendent beauty. The pictures located on the walls are eloquent by their silence and offer significant testimony; the pavement on which people tread is combined with small stones and is significant to mention in itself.

These spectacles strike the senses and delight the eye by drawing us near to [the martyr’s tomb] which we believe to be both a sanctification and blessing. If anyone takes dust from the martyr’s resting place, it is a gift and a deserving treasure. Should a person have both the good fortune and permission to touch the relics, this experience is a highly valued prize and seems like a dream both to those who were cured and whose wish was fulfilled. The body appears as if it were alive and healthy: the eyes, mouth, ears, as well as the other senses are a cause for pouring out tears of reverence and emotion. In this way one implores the martyr who intercedes on our behalf and is an attendant of God for imparting those favors and blessings which people seek. (Sanidopoulos, text in English with emphasis added; cf. Pelikan p. 106; see also Migne’s Patrologia Graeca 46:737-740, text in Latin and Greek; and Cavarnos’ text in Greek).

Gregory’s panegyric to Theodore the Recruit is significant for several reasons. First, it tells us that the fourth-century churches had numerous images on their walls. Second, the early Christians venerated the relics of the martyrs. And third, the early Christians asked the martyrs to pray for them. From the phrase “the body appears,” i.e., the image of Theodore, followed by “one implores the martyr” in the next sentence we can infer that early Christians were looking at the icon of Saint Theodore and asking his prayers. The early Christians did not view the martyrs as having godlike powers, but as God’s servants who assisted them in their prayers. What Gregory described here parallels the present-day Orthodox experience of venerating an icon.

Gregory of Nyssa’s description of icon veneration in the fourth century may come as a surprise to some readers. Many are not aware of this sermon due to the fact that it is not among those published in the widely accessible Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers series but in the less accessible Patrologia Graeca compiled by Jacques-Paul Migne. It was only because Jaroslav Pelikan made reference to Saint Gregory’s panegyric in his Imago Dei (p. 106) that I became aware of this early witness to icon veneration. The fact that Pelikan, a renowned scholar at Yale University, referenced Gregory of Nyssa’s oration seems to attest to the text’s veracity. Another attesting source is Quasten’s Patrology (Vol. III p. 278). Lectio-Divina.org has a useful discussion about the text for Gregory Nyssa’s oration on Theodore the Martyr. I have not found any suggestion that Gregory’s oration is spurious.

The veneration of martyrs as described by Gregory of Nyssa was not all that unusual. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) described how people prayed at the site of the martyrs’ relics and were healed (City of God Book 22 Chapters 8-10; NPNF Vol. 1 pp. 490-492; Latin version in Migne). Augustine wrote City of God shortly after the sacking of Rome in 410, which makes it almost contemporaneous with Gregory’s oration. The evidence seems to suggest that the practice of praying to the saints (the martyrs) was quite popular among the laity. The bishops, rather than oppose this practice, embraced it and sought to bring balance. Augustine recounts how Ambrose of Milan dissuaded Augustine’s mother from bringing baskets of food to the martyrs’ shrine but rather a heart full of prayer (Confessions Book 6 Chapter 2; NPNF Vol. 2 p. 90).

Augustine’s description of the early Christian veneration of the martyrs closely resembles Gregory’s panegyric dedicated to Theodore. The only difference is that Augustine made no mention of images. One way to understand this omission is to view icons as an incidental detail while attention is given to the prayer offered to the departed saint. When I venerate an icon of Christ and the saints, my mind is more on the prayer I am going to make than on the icon. When I ride the bus, my mind is more on my destination than on whether or not the bus has passed inspection or whether the bus driver has a valid driver’s license. In the ordinary life of an Orthodox Christian more is said about our need to pray than about the legitimacy of icons. Icons are important because they assist us in our prayer life and our worship of Jesus Christ. It is only because of the objections of the iconoclasts that Orthodox Christians have found it necessary to explain the need for icons.

Are Icons a Reversion to Pagan Idolatry?

One criticism Protestant iconoclasts have made about icons is that it would lead to the saints being viewed as resembling the pagan deities. However, Gregory of Nyssa makes clear that the martyrs were God’s servants. The Latin version has the phrase “satellite Dei” (attendant of God).

. . . supplicants offer prayers as if they were the messengers of God praying, as if they were invoking the receiver of gifts when he wills.

. . . supplices preces offerunt tanquam satellite Dei orantes, quasi accipientem dona cum velit, invocantes. (Migne p. 739)

Unlike Greco-Roman paganism which assumed that the various deities had power in themselves to grant the wishes of those who supplicated them, this passage assumes that there is one supreme God. The underlying assumption here is that the Church Triumphant in heaven is praying on behalf of the Church Militant on earth. The idea of the martyrs interceding on behalf of the living can be found in the book of Revelation: 6:9-11, 7:9-15, and 20:4-6.

In the fourth century, the Roman Empire underwent a profound religious conversion. Christian monotheism had taken firm roots in the mindset of the Christian converts. It appears that Protestant iconoclasts have likened Orthodox icon veneration to Greco-Roman paganism solely on the basis of the external similarities. For the Protestant critique to have merit, the Protestant iconoclasts must show how the early Christian martyr cults paralleled Greco-Roman paganism with respect to internal beliefs as well as external forms. This, they have yet to do.

Another evidence that the early Christian practice of praying to the saints was not a reversion to paganism can be seen in Augustine’s explanation how the miracles done by means of the martyrs testify to their faith in Jesus Christ.

For whether God Himself wrought these miracles by that wonderful manner of working by which, though Himself eternal, He produces effects in time; or whether He wrought them by servants, and if so, whether He made use of the spirits of martyrs as He uses men who are still in the body, or effects all these marvels by means of angels, over whom He exerts an invisible, immutable, incorporeal sway, so that what is said to be done by the martyrs is done not by their operation, but only by their prayer and request; . . . . (City of God, Book 22, Chapter 9, NPNF Vol. 2 p. 491; emphasis added)

Sive enim Deus ipse per se ipsum miro modo, quo res temporales operantur æternus, sive per suos ministros ista faciat ; et eadem ipsa quæ per ministros facit , sive quædam faciat etiam per Martyrum spiritus, sicut per homines adhuc in corpore constitutos ; sive omnia ista per Angelos, quibus invisibiliter, immutabiliter, et incorporaliter imperat, operetur ; ut quae per Martyres fieri dicuntur, eis orantibus tantum et imperiantibus, non etiam operantibus fiant; . . . . (De Civitate Dei, S. Augustini, Liber Vigesimus Secundus, Caput IX, in Migne p. 771; emphasis added)

The phrase “not by their operation” indicates that the saints do not have power in themselves but that the miracles were the result of their prayers to God. Here we learn how early Christians such as Augustine were able to accept the practice of praying to the martyrs without the early Church regressing to paganism. There was indeed a danger that the Christian laity in their sincerity might unwittingly syncretize their Christianity with pagan practices. Augustine’s mother’s practice of bringing baskets of food to the martyrs’ shrine is an example of that potential danger and Ambrose’s kindly pastoral advice showed how the early bishops directed the enthusiastic laity towards a devotional practice that was Christ-centered.

Therefore, in suggesting that the early Christians praying to the saints signified a reversion to paganism, Protestant iconoclasts have passed hasty judgment on the basis of outward form while being unaware of the profoundly Christian content of the early Christians’ veneration of the saints. Praying to the saints was not an add-on but rather the outworking of the profound implications of the Incarnation and Christ’s Resurrection. We see this in the opening line of City of God, Book 22, Chapter 9 from which the quote is taken:

To what do these miracles witness, but to this faith which preaches Christ risen in the flesh, and ascended with the same into heaven?” (NPNF Book 22 Chapter 9, vol. 2 p. 491).

The martyrs’ union with Christ in conjunction with Christ’s resurrection made possible their interceding on behalf of those still living on earth. Underlying all this is a profoundly sacramental worldview that many Protestants are not familiar with.

Partial Evidence for Icon Veneration

While Gregory’s panegyric is impressive evidence for the early veneration of icons, the argument would be a much stronger if there were other similar witnesses. But those who study early Christianity often find it necessary to work with what scarce evidence is available. Therefore, if we want to find evidence prior to the 380s, we will have to take into account partial-evidence that date back to the second and third centuries. These partial evidence bear witness to aspects of icon veneration: the presence of images in early churches, prayers to the martyrs, and relics being venerated. Rather than assert that the veneration of icons as a complete package goes back as early as the second century, I propose that the various aspects of icon veneration existed in embryonic form early on then developed and converged into icon veneration by the fourth century. In this way, the case can be made for icon veneration being part of early Christianity and not an accretion.

Baptistry – Dura-Europos Church circa 250

Roman Catacombs circa 200

Early Christian Images

Archaeologists discovered images in a Jewish synagogue and Christian church in the Syrian town of Dura Europos dating back to circa 250. Even earlier evidence are the images found in the catacombs that have been dated to the late 100s to the early 200s. The significance of these images lies in the fact that Christians across the Roman Empire were comfortable with images in their places of worship prior the Emperor Constantine’s acceptance of Christianity in 313. In other words, the presence of images in Christian churches cannot be attributed to new converts importing pagan practices as Protestant iconoclasts have alleged.

An ironic witness to the cultic use of images in the early Church is the outspoken curmudgeon, Tertullian (155 to 220). In his treatise On Modesty, Tertullian complained about the image of the Good Shepherd on the communion chalice:

“. . . to which, perchance, that Shepherd, will play the patron whom you depict upon your (sacramental) chalice.” (ANF Vol. 4 p. 85; emphasis added; NewAdvent).

Tertullian’s complaint is about an actual practice in the early Church. We learn that in the second century Christians were displaying images not only on the walls of the places of worship but also on the implements used in the Eucharist. While the presence of these images does not confirm the veneration of icons early on, they suggest the possibility. In many Orthodox parishes it is customary for the communicant to kiss the chalice immediately after receiving Holy Communion. It is possible that Christians in Tertullian’s time were doing something similar.

Tassilo Chalice c. 770-790

Protestant apologists have argued that the presence of images in these early places of worship at best support aniconism, not iconodulia. Where aniconism accepts the presence of images in churches for didactic purposes, it holds that early Christians did not bow down to these images or pray to them—the core of iconodulia. This is why Gregory of Nyssa’s Panegyric to Theodore the Recruit is so significant. It represents a missing piece of the puzzle that enables us to understand an early Christian practice in the late 300s, long before the cut-off point of 600. We see here the various strands of evidence coming together into one integrated practice.

An Early Prayer to Mary

Another partial evidence in support of the veneration of icons is the early Christian practice of praying to the Virgin Mary. (See my article: “An Early Christian Prayer to Mary.”) In the early 1900s, the John Rylands Library came into possession of a collection of very early papyri. Among the papyri are fragments of the New Testament that date to the early second century, just decades after the last books of the New Testament canon was written (Papyri 52). Relevant to our discussion is Papyrus 470 which dates to around 250 and contains an early liturgical prayer to the Virgin Mary—Sub Tuum Praesidium (Under Your Protection). The text reads:

Beneath thy compassion,

We take refuge, O Theotokos [God-bearer]:

do not despise our petitions in time of trouble:

but rescue us from dangers,

only pure one, only blessed one.

It is striking that Christians as early as the third century were praying to the Virgin Mary asking for her intercession. While praying to Mary is a familiar practice for Orthodox Christians, hardly any Protestants do the same. Again, it should be noted that this practice predates Emperor Constantine. Rather than assert that Sub Tuum Praesidium was accompanied by an image of Mary, I suggest that the two devotional practices stood alongside each other then gradually converged into one integrated practice. This to me is the best way to make sense of the early evidence. Rather than insist dogmatically that the veneration of icons was present from the very beginning, I am open to a development of belief and practice. In this way, it can be said that the veneration of icons has roots going back to the very early days of the Church and not some later accretion as Gavin Ortlund alleged. To validate the icon-as-accretion argument, evidence must be presented that an external, alien devotional practice was grafted onto early Christianity. This calls for several kinds of evidence: (1) a description of the alien devotional practice which originated from Greco-Roman paganism, (2) the name of the person or group who introduced this alien practice and an approximate date where the innovation occurred, and (3) an account of the spread of this alien practice until it became widespread among Christians.

St. Polycarp Before the Crowds

Polycarp’s Relics

Polycarp is regarded as one of the Apostolic Fathers, early Christians who had personal knowledge of the Apostles. In 155, Polycarp, a disciple of the Apostle John, was arrested and was burned at the stake. What is of interest to us is how the early Christians handled Polycarp’s bodily remains with great reverence and celebrated the anniversary of his martyrdom.

Accordingly, we afterwards took up his bones, as being more precious than the most exquisite jewels, and more purified than gold, and deposited them in a fitting place, whither, being gathered together, as opportunity is allowed us, with joy and rejoicing, the Lord shall grant us to celebrate the anniversary of his martyrdom, both in memory of those who have already finished their course, and for the exercising and preparation of those yet to walk in their steps. (The Martyrdom of Polycarp New Advent; emphasis added)

We learn two important facts from The Martyrdom of Polycarp. One is the reverence with which the early Christians handled his relics. The other was the fact that the early Christians celebrated the anniversary of his martyrdom. In The Martyrdom of Polycarp, we see elements of what would become the cult of the martyrs. It was widely believed that those who died a martyrs’ death stood in the presence of God interceding for those still living on earth. This belief can be traced to the Book of Revelation 6:10-11, 7:13-14, and 20:4-6. The cult of the martyrs is founded on the belief that the Church Militant on earth is surrounded by the Church Triumphant in heaven. This belief can be found in the Apostles Creed which affirms “the holy Catholic Church, the communion of saints.” J.N.D. Kelly in Early Christian Doctrines described how the early cult of the martyrs would develop over time into the “communion of saints”—the blessed state of being in fellowship with the Virgin Mary and martyrs, meeting and conversing with them (Kelly pp. 488-490). This suggests that Saint Gregory’s oration celebrating Theodore’s martyrdom, given in 386, has roots going back to Polycarp’s martyrdom in 155.

What links icon veneration to the venerating of relics and offering prayers to the Virgin Mary and the saints is the sacramental worldview in which the spiritual realm overlaps the material world we inhabit. Hebrews 12:1 informs us that we are surrounded by an invisible multitude of saints (the great cloud of witnesses). The disenchanted worldview of modernity in which the spiritual and material are viewed as disparate and separate from each other has had a profound impact on Protestantism. Magisterial Protestants would say that at best icons in churches serve an educational purpose but do not mediate the presence of Mary and the saints. Underlying Protestant aniconism is a secular worldview in which the spiritual-material divide is bridged via an intellectualized faith but personal communication with the departed saints is ruled out. This has resulted in many Protestants admiring the saints as remote historical figures, not as intimate elder brothers and sisters in Christ. While images of saints might be permitted, Protestant pastors will discourage their parishioners from praying to the saints. Tragically, today’s Protestants have become estranged from their spiritual ancestors. See Alexander Schmemann’s For the Life of the World, especially the appendices: “Worship in a Secular Age” and “Sacrament and Symbol.” In it he presents the Orthodox worldview in a manner that is clear and comprehensible to theologically astute Protestants and Evangelicals.

Were the Early Apologists Anti-Icon?

The Apologists stand between the Apostolic Fathers, who had personal knowledge of the original Apostles, and the Church Fathers, who lived after the Apostles. They sought to defend Christianity to the pagan authorities and philosophers in the second and third centuries. Thus, the Apologists represent an important source for understanding early Christianity. It should be kept in mind that for Orthodoxy the Apologists with a capital “A” are saints, e.g., Athenagoras, Justin Martyr, and Melito of Sardis. However, not all early theologians are regarded as Apologists or Church Fathers. One good example is Clement of Alexandria, whom the Orthodox regard with cautious admiration.

Protestant apologists have argued that the Apologists were fiercely anti-icon. They have piled up quotes upon quotes seeking to show that the early Christians were anti-icon, often with no regard to the context. Gavin Ortlund (26:17) cites Clement of Alexandria’s Stromata, Book 7 Chapter 5, which has the sentence:

Works of art cannot then be sacred and divine. (ANF vol. 2 p. 530)

Yet, a few lines down that same page, Clement writes:

But how can He, to whom the things that are belong, need anything? But were God possessed of a human form, He would need, equally with man, food, and shelter, and house, and the attendant incidents. (ANF vol. 2 p. 530; emphasis added)

Without taking into the account the context in which Clement was writing, one would think that Clement here is denying the Incarnation—a preposterous notion. The way around this is that the early Christians were referring to God the Father in their critique of pagan idolatry, not to Jesus, the Incarnate Son of God. Similarly, Clement was deriding the pagan notion of finite gods being located in specific locations in contrast to the infinite, transcendent God of the Bible. Read uncritically, Clement’s objection to using architecture and the arts in the worship of God would seriously undermine the making of the Tabernacle in the book of Exodus. The God of the Bible did not abhor matter as the Greek Platonists did but in the fullness of time sent his Son to become man. In the Incarnation the Infinite God became finite man for our salvation. This would be the linchpin of John of Damascus’ theological defense of icons (On the Holy Images 1:16). All too often Protestant apologists have used the early Christian Apologists for convenient prooftexts. They cite the Apologists with little regard for the context from which the quotes were taken. I hope to do an article on the Apologists’ iconoclasm in the future.

Connecting the Dots

In response to Gavin Ortlund’s claim that the veneration of icons is a late accretion, I have presented several pieces of evidence. The first is Gregory of Nyssa’s panegyric which describes the veneration of icons. The oration which dates to the 380s is far earlier than the 600s, the period that Ortlund assumes icon veneration to have originated. Then I showed several partial evidence: (1) archaeological evidence of images in Christian places of worship that date to the second and third centuries, (2) a third century prayer to the Virgin Mary, and (3) the veneration of Polycarp’s relics dating back to the mid second century. These partial evidence suggest that icon veneration described by Saint Gregory has roots going back even earlier to the third and second centuries.

The fact that Gregory’s oration predates Pastor Ortlund’s cut-off point of 600 by more than two centuries rebuts his claim that icon veneration is an accretion. The partial evidence presented can be understood to be aspects of icon veneration that go back even earlier to the second and third centuries. It is suggested that in the early Church there were various devotional practices that would converge by the 300s into icon veneration. Thus, the various evidence taken together support the antiquity of icon veneration.

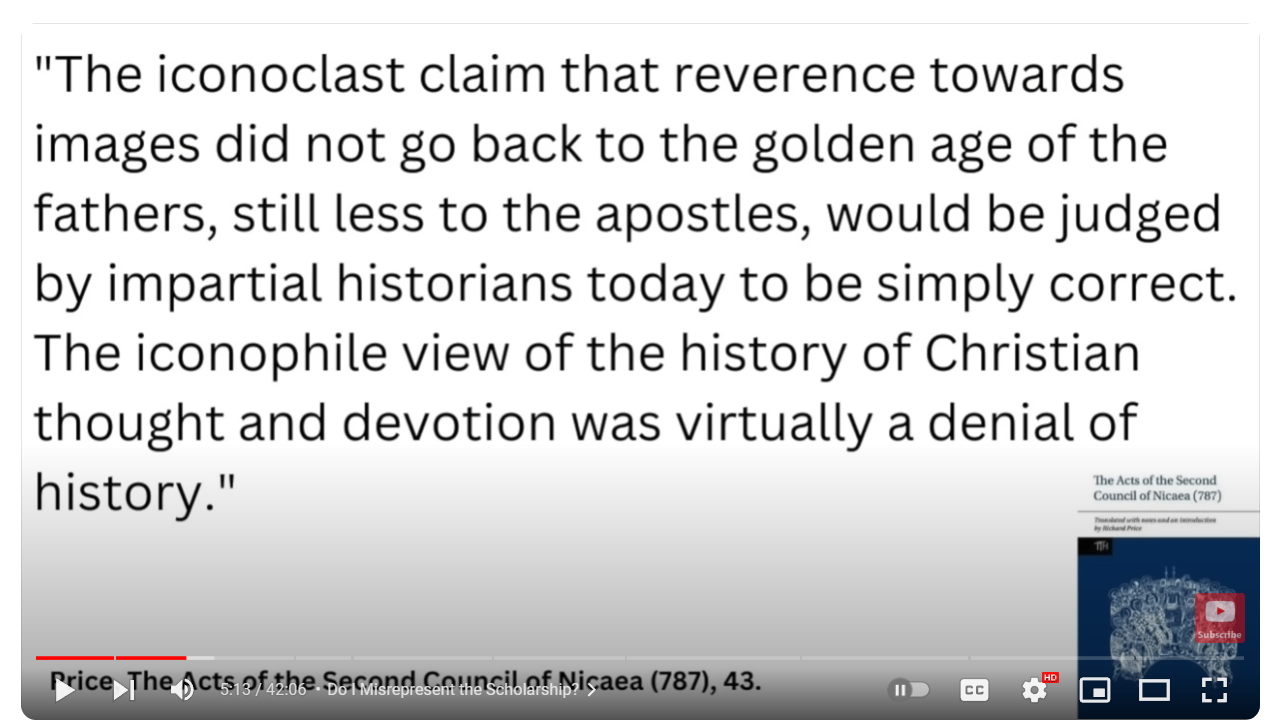

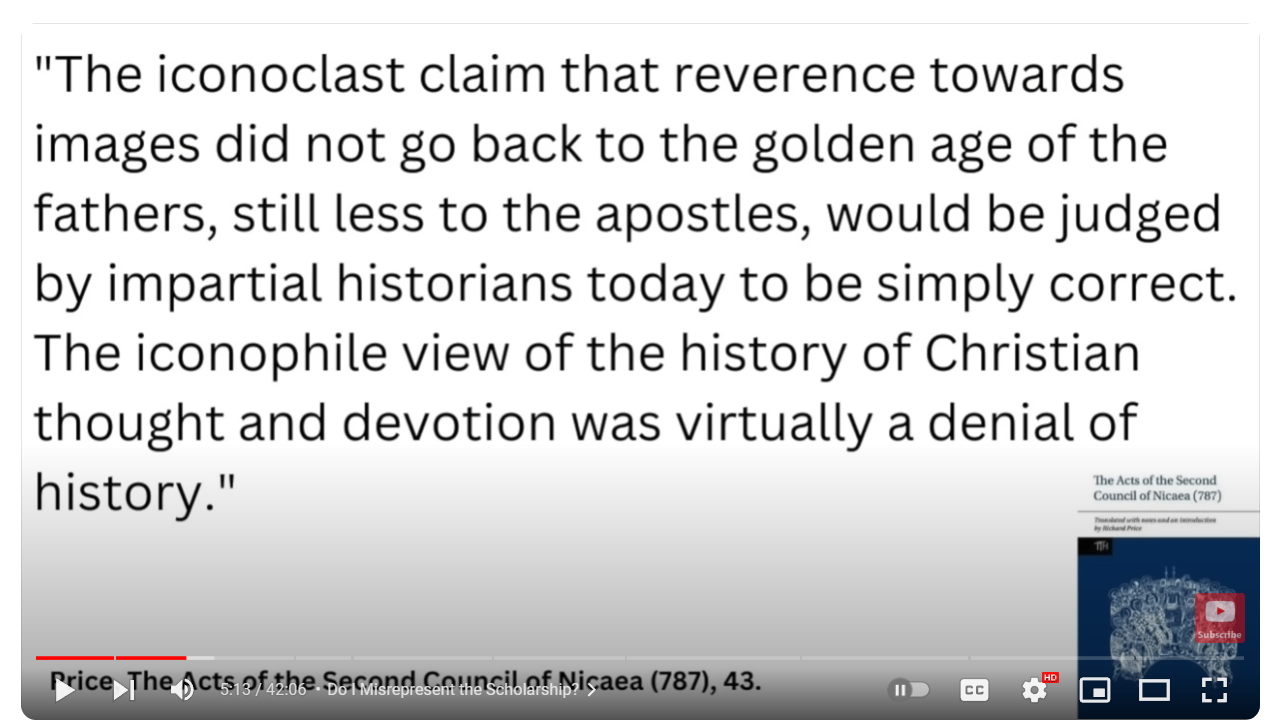

Gavin Ortlund quoted Richard Price’s The Acts of the Second Council of Nicea which asserted that the veneration of icons did not “go back to the golden age of the fathers.” [“Craig Response toTruglia” at the 5:14 mark]

Here Gavin Ortlund is invoking the authority of secondary sources. However, greater weight must be given to primary sources, to the evidence. Gregory of Nyssa’s “Panegyric to Theodore the Recruit” seems to punch a gaping hole in the passage from Richard Price. I would be very interested in how Ortlund understands Saint Gregory’s affirmation of icon veneration and praying to the saints which dates back to the golden age of the fathers—300s and 400s.

Static Tradition versus Dynamic Tradition

The recent debate over icon veneration has taken place against the backdrop of two paradigms of doctrinal development: (1) the static paradigm and (2) the dynamic paradigm. In the static paradigm, it is assumed that present-day Orthodoxy ought to be identical with the doctrines and practices of the early Church. If a discrepancy can be found between the two then the modern counterpart must be judged inferior or even invalid. Many Orthodox Christians seem to hold to a static paradigm of Holy Tradition. This obliges Orthodox apologists to argue for the full-blown practice dating back to the second or third centuries. It sets a very high standard of evidence. Faced with the scarcity of evidence, some have argued from silence—that the full-blown practice has been there all along but out of sight.

The static paradigm of church history is quite popular among Protestants. Many Protestants hold the New Testament Church as their ideal and view church history after the first century as a period of decline—especially with Emperor Constantine’s embrace of Christianity. The magisterial Reformers sought to recover the original, pure Christianity prior to the later corruptions of Medieval Catholicism. The English Puritans in the 1600s and the American Restorationist movements of the 1800s went further in seeking to recreate a pure Christianity by stripping away unbiblical accretions. It behooves us to be aware of the influence of the static paradigm of doctrinal development as we debate the validity of icons and icon veneration.

The dynamic Tradition paradigm assumes that the early Church’s core beliefs would over time become more explicit and its practices would take on more elaborate forms. The assumption here is that despite the differences in outward form there remains an inward continuity. This pattern of development can be seen in the way the Last Supper evolved into the Eucharist; the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15 set a precedent for the First Ecumenical Council (Nicea, 325); and the full-fledged doctrine of the Trinity goes back to the baptismal formula in Matthew 28. Likewise, church polity coalesced early on into the monarchical episcopate as the universal norm. For Orthodox apologists, the advantage of the dynamic Tradition paradigm is that it allows for the incomplete and partial evidence that often frustrate church historians. With this paradigm I do not have to make the strained argument that the veneration of icons was present in the early Church but hidden from view until the 600s and 700s. I can argue that there are precedents dating back to the early Church that evolved in form while retaining the original meaning. This approach enables me to affirm continuity in Tradition without jettisoning the scholarship and methods I acquired as a church history major at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary (South Hamilton, MA).

There is a biblical basis for the dynamic paradigm of Tradition. Jesus promised his disciples that he would send them the Holy Spirit:

When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all truth . . . . (John 16:13; RSV)

This passage serves as a guarantee against a catastrophic apostasy derailing the early Church—the underlying premise of the Protestant paradigm of church history. It assures the Christian that there will be a continuity of truth that links the present-day Church with the original Apostolic Church. Just as the Holy Spirit inspired the Apostles and the New Testament writings, so likewise the Holy Spirit inspired the bishops, the Apostles’ successors, in the safeguarding of Apostolic Tradition. This verse does not confine the Holy Spirit’s inspiration to the Bible. The Holy Spirit inspired apostles, pastors, and teachers, leaders who shepherded the Church (Ephesians 4:11). The ordained clergy does this through the correct interpretation of Scripture and by defending the Church against heresy. In like manner, the Holy Spirit inspired and guided early church councils against false teachings (Acts 15:28). Orthodoxy’s broader understanding of the Holy Spirit and divine inspiration opens the way for church history as sacred history. The miracle of the Incarnation did not end with Christ’s ascension to heaven but continued through the Church, the Body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12).

Additional support for the dynamic paradigm can be found in the Parable of the Mustard Seed:

The kingdom of heaven is like a grain of mustard seed which a man took and sowed in his field; it is the smallest of all seeds, but when it has grown it is the greatest of shrubs and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches. (Matthew 13:31-32; RSV)

This parable was fulfilled in the fourth and fifth centuries, the golden age of early Christianity. This period saw the early Church flourishing in worship and doctrine, e.g., the Liturgies of Saint Basil and Saint John Chrysostom, the Ecumenical Councils which gave us the Nicene Creed and the Chalcedonian formula, and the proliferation of theologians known as Church Fathers and Desert Fathers. It was during this fruitful period of church history that Gregory delivered his panegyric to Theodore which described the early Christians’ use of icons in their veneration of the martyrs. The legacy of the golden age of early Christianity continues on in present-day Orthodoxy whereas it has become a forgotten past in other traditions. Some Protestant critics might respond that the present form of Orthodoxy with all of its complexity is a Medieval accretion of the earlier period. However, it should be noted that mainstream Protestantism has also been receptive to elaborate confessional formulas and liturgies. It was only with the rise of Puritanism in the 1600s and the Restorationist movements in the early 1800s that Protestants became averse to elaborate liturgies and theological formulas. The stripping away of developed theology and worship favored by these two movements stem from their being creatures of modernity than their Christian heritage.

The dynamic paradigm is based on the Pentecostal reading of church history—church history being the result of the Holy Spirit’s flowing into human history. By assuming the Holy Spirit’s continued presence beyond the Book of Acts to the present day, the dynamic paradigm of doctrinal development sanctifies church history. Looking back on my time as a church history major at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, I am struck by how secular my approach to church history was. Without faith in the Holy Spirit’s guidance, we become vulnerable to thinking that theology is largely an intellectual enterprise in which theologians debate other theologians and church history largely the outcome of power struggles among rival factions.

However, when I began to shift towards a sacramental understanding of the Church, I came to view the Church as a supernatural entity endued with the life of Christ. Another shift came when I understood the Church to be the holy commonwealth entrusted with Apostolic Tradition. The Holy Spirit’s presence in history opens the way for the dynamic approach to doctrinal development. This paradigm of church history allows us to see the Holy Spirit at work as informal devotional practices such as prayers to the martyrs converged with the images inside early churches. In this paradigm we see the Holy Spirit guiding the Seventh Ecumenical Council’s formal endorsement of the veneration of icons and inspiring John of Damascus’ erudite apologia for icons based on the Incarnation.

Church History Like a Mango Tree

Young Mango Plant

Mature Mango Tree

I have used the image of a mango plant that over times grows into a huge fruit-bearing tree to illustrate the dynamic paradigm of doctrinal development. See my article: “Responding to Rev. John Carpenter – Round 2.” While the mature mango tree looks radically different from the tiny mango plant that just sprouted out the ground, there is an essential continuity between the two. The fruit and flowers may not be visible to the eye in the young mango plant, but given time the inherent potential in the mango plant will become visible to all and to the benefit of everyone. They are organically inherent to the mango tree and therefore cannot be considered accretions. An accretion would be a belief or practice exterior and alien to early Christianity. (See also Newman’s Development of Doctrine Chapter VIII; Application of the Third Note of a True Development – Assimilative Power; §1 Number 7, where he uses the metaphor of a seed growing into a stalk, a shrub, then a full-grown tree.)

Gavin Ortlund’s complaint about icon veneration being an accretion leads me to believe that he holds to the static paradigm of doctrinal development. Yet in his other videos, it is clear that he is sensitive to historical development in doctrine and practice. This is to be expected of someone who has a doctorate in historical theology. In light of that, I find his resistance to the possibility of doctrinal development with respect to the veneration of icons puzzling. From the standpoint of the dynamic paradigm of Tradition, Ortlund’s criticism is premature. It is like complaining that the fruit and flowers of a blooming mango tree are alien accretions that must be pruned as soon as possible, which would leave us with a big barren tree bereft of beauty and sweetness.

Moreover, it is risky to dismiss out of hand the development of doctrine argument. So much of what is essential to Christianity emerged as a result of historical development. The biblical canon was not finalized until the fourth century. Athanasius’ Thirty-Ninth Festal Letter (367) and the Third Council of Carthage (397) listed the books comprising the New Testament. Until then, there was debate about which books were to be included or excluded from the New Testament. Christ’s divinity, which many Protestants and Evangelicals, accept without question was not formally recognized as dogma until the First Ecumenical Council in 325. What many do not realize is that the doctrine of Christ’s divinity is a hard-won prize that resulted from the defeat of various heresies in the 200s and early 300s. The full-fledged articulation of the Trinity as one Essence in three Persons did not take place until the Cappadocian Fathers (Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus) in the late 300s. Early Christian worship reached fruition in the liturgies of Saint Basil the Great and Saint John Chrysostom in the late 300s and early 400s. It was in this context that Gregory of Nyssa’s Panegyric to Theodore bore witness to the veneration of saints and their icons. In other words, to dismiss out of hand the development of doctrine apologia for icons imperils the biblical canon, Christology, and Trinity. It would result in a severely truncated understanding of church history grounded in willful ignorance of historical evidence. What I am proposing here seeks to integrate faith with reason within the discipline of historical theology.

John Henry Newman’s Development of Christian Doctrine

The concept of doctrinal development was made famous by John Henry Cardinal Newman’s Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), which he wrote when he was in transition from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. The concept of doctrinal development is more of a metatheory of theology than a specific doctrine. It is an attempt to understand how doctrine interacts with history and doctrine as a product of historical forces. This is a radical shift from the traditional approach to theology as logically related propositions and categories. The traditional Western theology derives much of its methodology from philosophy and relies heavily on deductive logic.

Newman’s essay on doctrinal development reflects the intellectual climate of the mid and late 1800s. Among the intellectual currents of the time were: (1) the ascendency of theological liberalism in the Church of England, (2) the emergence of church history as a rigorous academic discipline, and (3) Hegel’s teleological understanding of history. Newman’s thinking was not influenced by Charles Darwin’s On the Origins of Species, which was published shortly afterwards in 1859. While Newman was responsible for making the concept of doctrinal development widely known, he was not the first theologian to take an evolutionary approach to theology. A similar approach was being used in the Reformed tradition at the same time. In 1844, just one year before Newman published his essay, Philip Schaff presented his evolutionary approach to church history in his inaugural speech at the Mercersburg Seminary. His inaugural address would be published in The Principle of Protestantism (1845).

Newman’s proposal of doctrinal development was first resisted by the hierarchs of the Roman Catholic church. However, by the 1960s the Catholic church would acknowledge this principle in the document Verbum Dei.

This tradition which comes from the Apostles develop in the Church with the help of the Holy Spirit. (5) For there is a growth in the understanding of the realities and the words which have been handed down. (Verbum Dei §8)

The concept of doctrinal development can be cause for concern. Pope Francis’ invoking of doctrinal development in his authorization of female acolytes is grounds for concern among the Orthodox and serves as a warning about using the concept uncritically.

There has not been much interaction by Orthodox theologians with Newman’s theory of doctrinal development (Lattier 2012, p. xiv). Overall, Orthodoxy’s attitude to Newman’s doctrinal development has been skeptical and even hostile (see Lattier 2011). While the early Church Fathers affirmed an unchanging Tradition, there were Church Fathers—for example, Gregory Nazianzus (Orations 31:25-27)—who appealed to the Church’s growing understanding of the divinity of the Holy Spirit (J.H. Walgrave). This allows for a cautious openness by Orthodox Christians to the dynamic paradigm of church history.

The concept of doctrinal development is best used as a way of understanding church history. It should not be used as a methodology for doctrinal formulation. In Orthodoxy the emphasis has been on theology as the faithful reception of Tradition than theology as a creative intellectual project. In the wrong hands the concept of doctrinal development can be misused with dubious or even catastrophic results. Theological liberals find the idea of doctrinal development appealing as it offers justification for new practices that are essentially adaptations to contemporary culture. It can even be used to justify drastic doctrinal U-turns. Newman used doctrinal development to justify papal supremacy (Chapter 4 Section III). The Mercersburg theologians, John Williamson Nevin and Philip Schaff, used the organic, evolutionary approach to church history to argue for the eventual reuniting of Protestantism with Roman Catholicism. See Schaff’s The Principle of Protestantism (pp. 216-217). A dynamic approach to church history without Holy Tradition as the authoritative framework is highly problematic.

Additional Support from Scripture

As noted earlier, the conversation between Protestants and Orthodox over icons has undergone a shift. Where before the debate was about the presence of images in Old Testament places of worship, the focus has shifted to the veneration of images. Protestant apologists have for most part conceded that the Bible does allow for images in places of worship, e.g., Moses’ Tabernacle and Solomon’s Temple. However, they now argue that these images served either decorative or didactic purposes but in no way were used for the worship of God. Likewise, they have acknowledged that in the Old Testament people have bowed down to other humans as a form of social respect but in no way connected to worship. The Protestant apologists insist that evidence be shown in support of veneration in the context of worship. While biblical evidence for veneration of objects or people in connection with the worship of God is scarce, they do exist. For example, there are two psalms that talk about bowing down to the Temple.

But I through the abundance of thy steadfast love

will enter thy house,

I will worship toward thy holy temple

In the fear of thee. (Psalm 5:7; RSV; emphasis added)

[8 ἐγὼ δὲ ἐν τῷ πλήθει τοῦ ἐλέους σου εἰσελεύσομαι εἰς τὸν οἶκόν σου,

προσκυνήσω πρὸς ναὸν ἅγιόν σου ἐν φόβῳ σου.] [LXX Source]

| חוַֽאֲנִ֗י בְּרֹ֣ב חַ֖סְדְּךָ אָב֣וֹא בֵיתֶ֑ךָ אֶשְׁתַּֽחֲוֶ֥ה אֶל־הֵיכַל קָ֜דְשְׁךָ֗ בְּיִרְאָתֶֽךָ: [Source; Emphasis added] |

|

|

Then, there is Psalm 138:2 [137:2] which reads:

I bow down towards your holy temple

And give thanks to thy name for thy

Steadfast love and thy faithfulness;

For thou hast exalted above everything

Thy name and thy word. (Psalm 138:2; RSV; emphasis added)

[2 προσκυνήσω πρὸς ναὸν ἅγιόν σου

καὶ ἐξομολογήσομαι τῷ ὀνόματί σου

ἐπὶ τῷ ἐλέει σου καὶ τῇ ἀληθείᾳ σου,

ὅτι ἐμεγάλυνας ἐπὶ πᾶν ὄνομα τὸ λόγιόν σου.] [LXX Source; Emphasis added.]

באֶשְׁתַּֽחֲוֶ֨ה אֶל־הֵיכַ֪ל קָדְשְׁךָ֡ וְא֘וֹדֶ֚ה אֶת־שְׁמֶ֗ךָ עַל־חַסְדְּךָ֥ וְעַל־אֲמִתֶּ֑ךָ כִּֽי־הִגְדַּ֥לְתָּ עַל־כָּל־שִׁ֜מְךָ֗ אִמְרָתֶֽך [source; Emphasis added.]:

The biblical principle here is that bowing towards a physical object such as Solomon’s Temple was permissible because the Temple was where God’s presence dwelt. The fact that the Greek word proskuneo (to bow down in worship) points to something other than mere social honorifics. It comes as no surprise then that the Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council used proskuneo in its affirmation of icons.

Another important example of veneration in the Bible can be found in Daniel 2:46-47 where King Nebuchadnezzar bows down to the Prophet Daniel.

46 Then King Nebuchadnez′zar fell upon his face, and did homage to Daniel, and commanded that an offering and incense be offered up to him. 47 The king said to Daniel, “Truly, your God is God of gods and Lord of kings, and a revealer of mysteries, for you have been able to reveal this mystery.” (RSV; emphasis added)

46 τότε Ναβουχοδονοσορ ὁ βασιλεὺς πεσὼν ἐπὶ πρόσωπον χαμαὶ προσεκύνησε τῷ Δανιηλ καὶ ἐπέταξε θυσίας καὶ σπονδὰς ποιῆσαι αὐτῷ.

47 . . . δηλῶσαι τὸ μυστήριον τοῦτο . . . . [LXX Source; Emphasis added.]

|

|

| מובֵּ֠אדַיִן מַלְכָּ֚א נְבֽוּכַדְנֶצַּר֙ נְפַ֣ל עַל־אַנְפּ֔וֹהִי וּלְדָֽנִיֵּ֖אל סְגִ֑ד וּמִנְחָה֙ וְנִ֣יחֹחִ֔ין אֲמַ֖ר לְנַסָּ֥כָה לֵֽהּ]:[Source; Emphasis added.] |

|

What is striking about Daniel 2:46 is that it uses the same Greek word as Psalms 5:7 and 138:2 (proskuneo). What is even more striking is that even more than bowing down to Daniel, King Nebuchadnezzar ordered the offering of sacrifice and incense to Daniel. The Hebrew word sagad in Daniel 2:46 is much more forceful than Psalms 5:7 and 138:2 which use the more generic shahah. Keil and Delitzsch note that the word סְגִ֑ד (sāgad) (a Hebrew word borrowed from Aramaic) was used exclusively for divine homage (p. 112). It is worth noting that nowhere in the text is there any condemnation of Nebuchadnezzar for doing this. The absence of condemnation is likely due to the fact it was Yahweh, the one true God—Daniel’s God—who was being honored. In verse 47, we read of Nebuchadnezzar acknowledging that Daniel’s God is “God of gods and Lord of kings.” The tolerance with respect to Nebuchadnezzar’s bowing to Daniel is likely forbearance of the sincerity of a polytheistic pagan who for the first time has encountered the one true God.

The New Testament, however, seems to present us with discontinuity. We read about the Apostle Peter dissuading Cornelius the Centurion from bowing down to him in Acts 10:25 [πεσὼν ἐπὶ τοὺς πόδας προσεκύνησεν] and Saint John being rebuked by the angel in Revelation 22:8-9 [ἔπεσα προσκυνῆσαι ἔμπροσθεν τῶν ποδῶν τοῦ ἀγγέλου]. Protestant iconoclasts have used these two passages to argue against bowing to icons while ignoring bible passages that point in a different direction. We should not read these verses woodenly, but rather use them to discern biblical principles of worship. The basic principle here is biblical worship can include bowing down towards objects or people closely associated with the one true God, e.g., Solomon’s Temple and the Prophet Daniel. Likewise, biblical worship disallows acts of worship in which the creation/Creator difference is confused, e.g., Cornelius bowing down to Peter and John bowing to the Angel. Orthodoxy’s veneration of icons is grounded in the understanding that the worship of the one true God can include honor being showed to objects manifesting the divine Presence. By refuting the aniconic reading of Scripture, it is hoped that this sub-section will assure inquirers that there is a biblical basis for the venerating of icons and the saints.

Orthodoxy takes pain to ensure that honor must ultimately be attributed to God, not to the objects mediating his grace. For Orthodoxy, the primary locus of the divine-human encounter is the Liturgy, especially the Eucharist. For the Orthodox, the Eucharist is not a mere symbol of Christ’s Body and Blood but is actually the Body and Blood of Christ. Receiving Holy Communion facilitates our union with Christ and our participation in the life of the Trinity. Underlying the Orthodox veneration of icons is a sacramental worldview which assumes that the spiritual reality of heaven can overlap with our physical reality here on earth. Likewise, icons mediate the personal presence of the saints depicted. The saints are part of the invisible cloud of witnesses mentioned in Hebrews 12, who are with us and are praying for us. The Liturgy unites the Church Militant here on earth with the Church Triumphant in heaven in the worship of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Participating in the Liturgy brings healing to the alienation and inner emptiness of secular modernity and restores us to the ultimate reality of the Kingdom of God.

Protestantism possesses something of a sacramental worldview. When Protestants affirm that in the Bible God in some mysterious but very real way speaks to humanity, they are evincing a sacramental understanding. Here the divinely-inspired Scriptures mediates between the earthly and heavenly realities. Orthodoxy extends this sacramental understanding beyond the Bible to the Church as the Body of Christ, the Real Presence of Christ’s Body and Blood in the Eucharist, and to icons and prayers to the saints. Protestants and Evangelicals who are hungering for divine grace are drawn to the ancient liturgies, the Eucharist, and the Church Fathers, but many balk at venerating icons. However, icons are no mere trivia. Where the Eucharist comprises the center of Orthodoxy, the icons serve as the outer perimeter that safeguards the holy Mysteries. Many Protestant inquirers have struggled with the issue of icons. This author likewise has had to struggle with the issue of icons. Reformed iconoclasm may seem to be an impregnable barrier to Protestant inquirers but it can be surmounted through careful research, critical analysis, and prayerful reflection. Just as important is attending the Liturgy on Sunday morning. It is in the Liturgy that the Protestant inquirer can best observe and experience the role of icons in Orthodoxy. Come and see! (John 1:46)

Conclusion

Far from being a late accretion, Gregory of Nyssa’s panegyric to Theodore the Recruit shows that full-fledged icon veneration was present in the early Church as early as 386, long before 600 when Pastor Ortlund assumes the practice to have been introduced. Additional partial-evidence—images in early Christian places of worship, an early prayer to the Virgin Mary, and the veneration of Polycarp’s relics—were presented to show that icon veneration has roots going as far back as the second and third centuries. To rebut the Protestant argument for aniconism, biblical passages—Psalms 5 and 138, Daniel 2—have also been presented. These passages show objects and persons being venerated in the religious sense—not merely in the sense of reverence as social convention or images as educational decorations. The intent here is to show that icon veneration is rooted in Scripture and a genuine part of Christianity.

In constructing an apologia for the Orthodox veneration of icons for this article, I have reverse-engineered the historical development of icon veneration. Unlike the usual approach in which a long list of quotations is presented, I have had to connect various partial evidence into a pattern. I have taken this approach largely in consideration to the scarcity of evidence. With respect to Christology, Trinitarian doctrine, and the real presence in the Eucharist there exist an abundance of texts. These comprise the theological core of Orthodoxy. The veneration of icons serves as its protective perimeter. However, icons have become so intertwined with the other components of Holy Tradition that they now are part of the dogmatic structure of Orthodoxy.

Gavin Ortlund’s argument that icon veneration is an accretion shows how Protestant-Orthodox conversation about icons has advanced. (See my earlier article responding to John B. Carpenter’s attempt to engage Orthodoxy on icons.) I would like to thank Pastor Ortlund for elevating the tone and intellectual quality of the discussion regarding icons and icon veneration. Unlike before, many Protestants and Evangelicals now have some knowledge of the early Church, the Church Fathers, and the Ecumenical Councils. The conversation has shifted to other topics: the anathemas of the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II, 787), the theological rationale for icon veneration by the Seventh Ecumenical Council, and the validity of John of Damascus’ theological defense of icons based on the Incarnation. The disagreement over icons is far from trivial. They are profoundly consequential for our understanding of the Incarnation, our salvation in Christ, and the nature of Christian worship. Despite Gavin Ortlund’s pursuit of irenic ecumenism, the divide between Protestants and Orthodox over icons may be too wide for both sides to find common ground. It is hoped that by addressing Protestant objections to icons, this article will provide inquiring Protestants with good reasons to embrace the ancient Faith.

Robert Arakaki

References

Academic-Deutsche Bibel Gesellschaft: LXX and NA28.

Academic-Deutsche Bibel Gesellschaft: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS)

Anonymous (Church at Smyrna). “On the Martyrdom of Polycarp.” NewAdvent.org.

Robert Arakaki. “Responding to Rev. John Carpenter – Round 2.” OrthodoxBridge, 25 January 2019.

Robert Arakaki. “The Early Church Fathers: Babies or Giants?” OrthodoxBridge, 10 June 2016.

Robert Arakaki. “An Early Christian Prayer to Mary.” OrthodoxBridge, 3 May 2015.

Robert Arakaki. “A Response to John b. Carpenter’s ‘Icons and the Eastern Orthodox Claim to Continuity with the Early Church.” OrthodoxBridge, 16 September 2013.

Robert Arakaki. “Early Jewish Attitudes Toward Images.” OrthodoxBridge, 29 July 2013.

Augustine of Hippo. City of God. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Vol. 1 (Book 22, Chapters 8-10)

Latin version: Augustini. De Civitate Dei (Migne Patrologia Latina).

Augustine of Hippo. Confessions. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Vol. 1 (Book 6. Chapter 2)

Steven Bigham. Early Christian Attitudes toward Images. Orthodox Research Institute. 2004.

Cavarnos, ed. “Gregory of Nyssa’s Encomium on Theodoros (soldier and martyr of Amaseia and Euchaita, S00480)” in Figshare. Greek text of Gregory of Nyssa’s Oration.

Chabad.org. Book of Daniel Chapter 2 – Hebrew text.

Chabad.org. Tehillim (Psalms) – Chapter 5 – Hebrew text.

Chabad.org. Tehillim (Psalms) – Chapter 138 – Hebrew text.

Clement of Alexandria. “The Stromata, or Miscellanies (Book 7 Chapter 5).” Ante-Nicene Fathers Vol. 2.

Gregory of Nyssa. “EIS TON MEGAN MARTYRIA THEODORON/SANCTI AC MAGNI MARTYRIS THEODORE.” Migne: Patrologia Graeca 46:737-740.

John of Damascus. On the Holy Images. Project Gutenberg, 1898.

C.F. Keil and F. Delitzsch. Ezekiel, Daniel. Commentary on the Old Testament, Volume IX. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. Reprinted 1982. PDF version.

J.N.D. Kelly. Early Christian Doctrines. Revised edition. Copyrighted: 1960, 1965, 1968, 1978.

Daniel J. Lattier. “John Henry Newman and Georges Florovsky: An Orthodox-Catholic Dialogue on the Development of Doctrine.” (Doctoral dissertation (2012), Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/800

Daniel J. Lattier. “The Orthodox Rejection of Doctrinal Development.” Pro Ecclesia, Vol. XX No. 4 (2011), pp. 389-410.

Lectio-Divina.org. IN PRAISE OF BLESSED THEODORE, THE GREAT MARTYR.

McClintock and Strong. 1880. “Frankfurt, Council of.” The Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. James Strong and John McClintock; Haper and Brothers; NY; 1880.

Migne. “SANCTI AC MAGNI MARTYRIS THEODORI (pp. 737-470).”

Gregory of Nazianzus. Fifth Theological Oration – On the Holy Spirit. NewAdvent.org.

John Henry Cardinal Newman. An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. (Chapter IV, Section III “The Papal Supremacy”)

Gavin Ortlund. “Icon Veneration in the Early Church? Response to Craig Truglia.” 20 January 2023. [42:06]

Gavin Ortlund. “Icon Veneration is CLEARLY an Accretion!” [1:14:54] December 2022.

Jaroslav Pelikan. 1990. Imago Dei: The Byzantine Apologia for Icons. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Johannes Quasten. Patrology. Volume III: The Golden Age of Greek Patristic Literature – From the Council of Nicea to the Council of Chalcedon. Westminster, Maryland: Christian Classics, Inc.

Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, translators. “The Martyrdom of Polycarp.” New Advent.org.

John Sanidopoulos. “Panegyric to Great Martyr Theodore the Tiro (St. Gregory of Nyssa).” 17 February 2010.

Philip Schaff. 1845. The Principle of Protestantism. Lancaster Series on the Mercersburg Theology, Volume 1. Bard Thompson and George H. Bricker, editors. Philadelphia, Boston: United Church Press.

Alexander Schmemann. 1988. For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy. Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press: Crestwood, New York. PDF

OCA.org. “The Apologists.”

OCA.org. “Great Martyr Theodore the Tyro (Recruit).”

Tertullian. “On Modesty.” NewAdvent.org

Vatican. “The Christian Catacombs.”

Vatican. Verbum Dei.

Vatican News. “Pope Francis: Ministries of lector and acolyte to be open to women.” 11 January 2021.

J.H. Walgrave. “DOCTRINE, DEVELOPMENT OF.” Encyclopedia.com.

Recent Comments