Book Review: Early Christian Attitudes toward Images by Steven Bigham (2 of 4)

This blog posting is a continuation of an earlier review of Fr. Steven Bigham’s book. In this posting I will be reviewing and interacting with Bigham’s arguments in Chapter 2.

Chapter 2 examines early Jewish attitudes toward images. This is important because modern Protestant iconoclasm assumes that the early Christians inherited from the Jews a hostile attitude towards images. However, if it can be shown that there existed an open attitude toward images among early Jews then the basis for the hostility theory becomes problematic.

Steven Bigham notes that a distinction needs to be drawn between figurative art and pagan idols. He presents Jean-Baptiste Frey’s theory that an alternation took place between a rigorist and less rigorous interpretations of the Second Commandment (pp. 22-23). This challenges the implicit assumption that Jewish opposition to images to be fixed and unchanging. This new approach allows for more flexible readings of the biblical, rabbinical, and historical data. It is suggested that a liberal attitude towards images existed from the period of monarchy to the exile, then a rigorist attitude from the restoration to the Hellenistic period. Later, an accepting attitude was found among the Amoraïm, the successors to the Pharisees.

Biblical Evidences

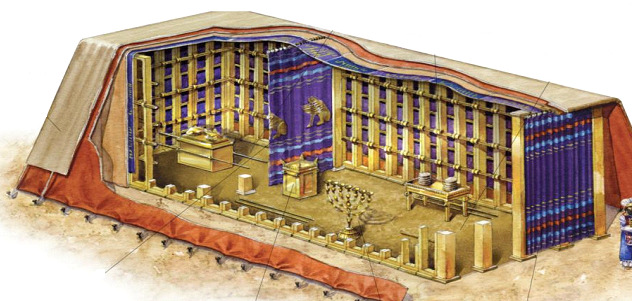

In sub-section 3 (pp. 22-32), Bigham reviews the biblical evidence for the use of art and images in Israelite worship: Exodus, Numbers, 1 Kings, Ezekiel, and Ecclesiasticus. In considering the Old Testament evidence, Bigham excludes passages relating to pagan idolatry and examines passages pertaining to Israelite worship (p. 26).

The Tabernacle in Exodus

Bigham finds it significant that Exodus which contained the Second Commandment (Exodus 20:2-6) also contained divine instructions for the construction of the golden cherubim over the Ark of the Testimony (Exodus 25:1-22), as well as the manufacture of curtains embroidered with cherubim (Exodus 26:1, 31). Bigham notes,

Placed so close to God himself and so intimately linked with the worship of the true God, the cherubim could never be separated from that worship and become themselves the object of misdirected, idolatrous worship. The cherubim on the Ark of the Testimony are a real problem for the advocates of rigorism, because God himself ordered Moses to have them made. The untenable contradiction in the divine commands disappears if we assume a relative interpretation of the 2nd Commandment that allows for non-idolatrous, liturgical images (p. 26).

All too often Protestant iconoclasm has equated idolatry with images, but this is too simplistic a definition. In his examination of the passage on the bronze serpent, Bigham notes that a sculpted image can be used in a non-idolatrous way. In response to the poisonous snakes sent to punish the Israelites, God ordered the making of a bronze serpent as a means of healing (Numbers 21:4-9). Later, King Hezekiah destroyed the serpent because the Israelites had begun to misuse it (2 Kings 18:1-4). Bigham notes:

This episode shows how an object, an image, normally not considered to be a idol, can become one. Idolatry is determined by a person’s intention and attitude toward an image, and not by the image itself (p. 27; emphasis added).

What Bigham has done here is to clarify the difference between religious art and idolatry. Furthermore, he has resolved an apparent contradiction in the Old Testament. His contextual understanding of the Old Testament passages avoids the difficulties caused by the more rigorist interpretations of the Second Commandment which would clash with subsequent passages that mandate the making of religious art.

In doing so, Bigham has rendered a tremendous service to Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. In any conversation on the Second Commandment and the proper role of images in worship, it is important that a balanced and biblically based definition of idolatry be established at the outset. If the two sides start from disparate definitions, the conversation will go nowhere. One question for the Reformed Christians and Evangelicals to consider is whether Bigham’s understanding is both biblical and balanced. If not, then they should put forward an alternative definition for the Orthodox to consider.

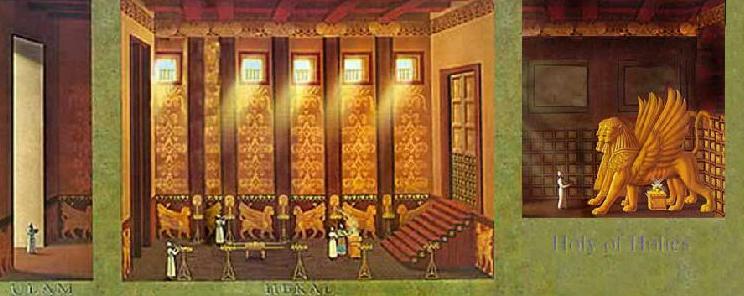

Solomon’s Temple

Bigham describes Solomon’s Temple in 1 Kings to be “a veritable art gallery and a nightmare for the advocates of the rigorist interpretation” (p. 28). King Solomon did not just replicate the Mosaic Tabernacle, but expanded and elaborated on the religious art work in connection with the worship of Yahweh. He had two enormous cherubim sculpted out of wood and overlaid with gold (1 Kings 6:23-28).

Solomon also had cherubim, palm trees, and open flowers carved on all the Temple walls and on the door to the Holy of Holies (1 Kings 6:29-31). Solomon made a molten sea which was placed over twelve statues of bulls (1 Kings 7:23-26). Furthermore, Solomon ordered the making of movable stands on which were carvings not just of cherubim, but also of lions and bulls (1 Kings 7:27-37).

The laudatory tone with which Solomon’s construction of the Temple for Yahweh was presented and the absence of any criticism makes 1 Kings quite problematic for those who hold to the iconoclastic position.

Solomon’s throne likewise was a huge work of art comprised of ascending steps with sculpted lions on both sides of each step leading to the throne (1 Kings 10:18-20). While less holy than the Temple, the throne was nonetheless the seat of the Lord’s anointed. This biblical passage points to an acceptance of images beyond the Temple into “secular” domains.

The favorable attitude among Jews continued into the post-exilic period. Bigham found in I Maccabees 1:22 and 4:57 evidence that the front of the Second Temple (520-515 BC) had been decorated with gold.

Ezekiel’s vision of the restored Temple continues the favorable attitude towards the use of images. As a prophecy it is significant because it extends the orthodoxy of religious images from the Mosaic Tabernacle of the past into the future worship of the Messianic Age, i.e., the Christian era. What is astounding is the profusion of images in Ezekiel’s future temple.

As far as the nearby wall of the inner and outer courts and along upon the wall all around within and without were depicted cherubim and palm trees, between cherub and cherub. Each cherub had two faces, the face of a man toward a palm tree on one side, and the face of a lion toward a palm tree on the other side. Thus it was depicted throughout the house all around. From the floor to the threshold, the cherubim and the palm trees were interspersed upon the walls (Ezekiel 41:17-20; OSB).

Taken together, the combined witness of passages across the Old Testament–from the time of Moses, the royal kingdom, and the prophetic tradition–presents an immense challenge to those who hold to the rigorist interpretation of the Second Commandment which disallows any and all forms of images in connection with the worship of Yahweh.

Non-Religious Images

In sub-section 5 (pp. 34-41), Bigham notes that additional evidence in support of Jewish tolerance or acceptance of images can be found in coins decorated with symbols like wreaths, horns of plenty, palms, cups and amphorae. It seems that these were accepted by Jewish authorities and rabbis. Similarly, Bigham found in Josephus’ The Antiquity of the Jews evidence that a certain prominent Jew, Hyrcanus, built a castle decorated with animals engraved on its walls (Bigham p. 37).

Carving of Lioness on Hyrcanus Palace

Josephus and Philo

In sub-section 6 (pp. 41-66), Bigham examines the evidence used to support the notion that first century Judaism prohibited “images of animate beings” on the basis of the Jewish Law. Two early sources, Josephus and Philo, have been used to bolster the claim that first century Judaism was by and large iconophobic. Bigham notes that behind this iconophobia was hostility to symbols of Roman rule. In other words the first century rigorist reading of the Second Commandment may be rooted just as much in politics as in religion (p. 44). Josephus in his Antiquities XVIII, III, 1, explained that Jewish opposition to the Romans display of the emperor’s image on military standards was due to the Second Commandment. However, Bigham notes:

We can also see Josephus’s motivation for painting the incident in religious, rather than its obvious political colors: The Roman authorities for whom Josephus wrote would be less offended by an insult to the emperor’s image based on the Jews’ well-known sensitivity in religious matters. In any case, Josephus’s presentation of the Law – “our law forbids us the very making of images” – is simply wrong since previous and subsequent Jewish history shows that such images were made and accepted under certain conditions (p. 45).

Recent Archaeological Discoveries

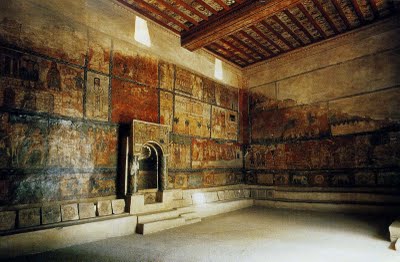

Dura Europos Synagogue. Source

In sub-section 7 (pp. 66-78), Father Bigham devotes several pages (pp. 66-70) to the archaeologists’ discovery of the Jewish synagogue in Dura Europos in 1932. Its complete burial allowed it to be preserved virtually intact. Due to the widespread assumption at the time that early Judaism was aniconic, the building was initially mistaken for a Greek temple.

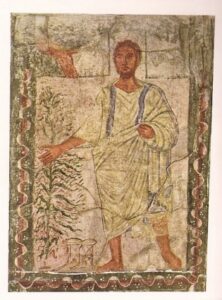

Image of Baby Moses – Dura Europos Synagogue. Source

The Dura Europos synagogue has profoundly challenged many misconceptions of early Jewish worship. The Dura Europos synagogue was not an isolated exception; other ancient synagogues had figurative arts (p. 67).

Moses and Burning Bush – Dura Europos. Source

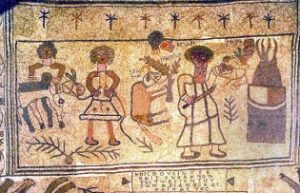

The Binding of Isaac – Beth Alpha. Source

This leads Bigham to write:

… it seems increasingly clear that Judaism led the way in developing figurative art and that Christianity followed, at least at the beginning. We have already seen that this hypothesis is upheld by many scholars. Even in areas other than art, we see the same phenomenon: early Christianity often modeled itself on its Jewish parent. “For the ancestry of most elements of early church worship, we must look to the synagogue rather than the home … (C. Filson)” (Bigham p. 68)

These archaeological evidences present serious problems for those who hold to the hostility theory, especially on the assumption that early Judaism was uniformly aniconic and iconophobic (Bigham p. 89). However, if first century Judaism accepted religious art, then it makes sense that the early Christianity reflected its Jewish roots. It can then be argued that it is the iconoclastic hostility theory that represents an alien intrusion into Christian history. The hostility theory was easy to uphold when the evidence was buried in the ground but when archaeological discoveries over the past century unearth these evidences that theory lost its foundation.

Religious Art in Early Jewish Synagogues

In addition to the startling discoveries at Dura Europos, there are other evidence of religious art in Jewish synagogues.

Zodiac – Synagogue Mosaic on Mt. Carmel. Source

The zodiac mosaic at Beth Alpha was not an isolated example. Other similar zodiacs have been found in Israel, e.g., Hammath Tiberias on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Naaran near Jericho, Sepphoris slightly north of Nazareth, En Gedi by the Dead Sea, and Huseifa near Mt. Carmel.

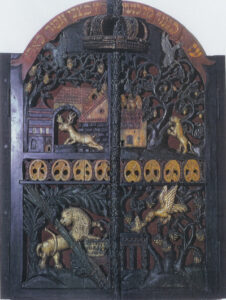

Religious Art in Medieval Judaism

An examination of religious art in medieval Judaism shows an attitude more accepting of religious art than that found in the Reformed tradition. One example is the carving of images on the ark in the Butzian Synagogue in Cracow, Poland.

Findings and Conclusion

Fr. Steven Bigham has conducted a wide ranging review of evidence about early Jewish attitudes toward images. The evidences include both biblical and extra-biblical sources, as well as secular literary sources and archaeological evidences. Bigham notes that the evidence is not conclusive, but it does call into question the assumption that early Judaism was uniformly and rigidly opposed to images. Early Jewish acceptance of images even in the context of synagogue worship lays the historical basis for the acceptance of images in early Christian worship.

Robert Arakaki

Is it true that Eastern Orthodox do not use musical instruments in worship? If this is so, could you explain why that is? I ask because many, if not most, of the original Reformers also wanted to eliminate the use of musical instruments in worship along with images. So I would like to compare and contrast the reasons between these two camps and possibly see where they do and do not agree. Thank you.

Erik,

Good question! I’m afraid I don’t know the answer to that. I’ll leave it to others to answer.

Robert

The Orthodox use of the human voice has as much to do with the structure of the Liturgy as it does the importance of the human voice in praising and giving thanks to God.

Choirs as we know them with multiphonic singing were not the norm. Antiphonal singing in a call-response format often with two sets of chanters. Priest or deacon, left chanter, right chanter along with congregational responses especially on the Lord have mercies. Call-response; offering-acceptance.

It is incarnational and Pentecostal at the same time demanding a response from creatures of God not man made artifacts.

It is worship of and with the living God not some performance about someone not really present.

The introduction of both pews and musical instruments has to do mostly with immigrants wanting to fit in with the prevailing culture. As we become more confident in who we really are, you will see less of both.

In small parishes, it works quite well to have the priest and one chanter with the congregation.

Icons are also incarnational combining heaven and Earth and providing a window into the Kingdom and connecting us with each other to the glory of God. There is simply too much experience with icons doing that for there to be any question about the reality.

I cannot emphasize too strongly that these are not ideas but living encounters with the Holy in intimate personal ways.

ERIK,

I am a life long Orthodox Christian and will respond in that context.

True that Orthodox Christianity do not use musical instruments within their services (Divine Liturgy, Vespers etc.) The music one experiences is from singing via choir, congregational responses and chanting. In basic terms the music comes from man’s lips to God’s ears.

In respect from David

David,

Thanks for sharing!

The Greek church down the road from me used an electronic keyboard for many years.

Interesting. Do they use it to find the right pitch or to accompany the choir through the entire song? If the latter, all the hymns or the seasonal ones assigned for that day?

Robert

I am utterly musically illiterate. All of your questions are good questions. I am simply not competent enough to answer them.

Jacob,

That’s okay. At the Greek Orthodox church I go to they use a keyboard to find the right pitch. From what I know Greek Orthodox churches at one time used organs then recently began moving towards the traditional format. The questions I asked were designed to find out where the church you mentioned stood on a continuum.

Robert

this is where i usually attend Divine Liturgy now. and sadly, they have a very sweet paid musician (lady) who uses the organ/keyboard to play the melody throughout most songs. but then there are rarely over 25-30 worshipers and no choir. sometimes she alone, sometimes with the cantor, sometimes with another older lady, sing and plays…me humming along (when in greek). rarely are there more than 4-5 of us congregants singing. i suspect we’d do just as well after a few weeks without the organ is she had a harp to get our note. but, they have the little organ there and have used it for years i’m sure. it’s not ideal of course…but then they believe there is no option. as a side note: today we had the Lord’s Prayer in six languages w/28 worshipers (english, bulgarian, russian, serbian, and german, then greek). cool international flavor to the worship…besides the beautiful words of the liturgy, songs, incense and icon of the saints surrounding us. most protestants, modern or not, would rightly see it as most unimpressive…but for the presence of the Holy Spirit among us all! 🙂 the Lord is merciful.

David,

Thanks for providing us the details. While it doesn’t sound like the ideal Orthodox style of singing, I think those of us outside of that parish should strive to be patient and understanding. I’m sure there’s some history behind what seems to be a deviation from Orthodox tradition. My guess is that we should encourage every parish to take small steps in the right direction. We should also let the priests and bishops know that we want to help improve the worship life of that parish.

Having people with musical backgrounds is a great asset to any Orthodox parish, especially small ones. One thing your parish could do is invite someone from the outside to give training in Byzantine chant or send a small contingent to a workshop on Byzantine chant. My new priest, Fr. Alexander Leong in Hawaii, does these kinds of workshops. Hint! Hint! 😉 Why don’t you ask the bishop to sponsor a regional workshop?

Robert

I know of finding the pitch. The old Scots Covenanters did the same thing with a whistle. I think the keyboard, if I recall correctly, was being played for most of the song, but I could be wrong.

Eph 5; 19 “speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord,”

&

Col 3;16 “Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom; teaching and admonishing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in your hearts to the Lord.”

I am new in my study of Orthodoxy but a life long member and former Minister from the “Church of Christ”. The CoC does not use musical instruments either. The above verses are the one most often quoted for that practice.

The words “making melody” ,in the original Greek, means to “pluck the strings of the instrument” and that verse tell us what instrument to “pluck” and that is the heart. Therefore, we have a command to use a instrument in our singing, it’s the heart. Only our heart / voices can ” teaching and admonish & speak” to one another. Instruments can’t do that.

I have started to lean toward the use of instruments as a “aid” to singing, as long as it don’t develop into a source of entertainment and replaces congregational singing.

It seems one issue in the study of Icons is similar to an issue with musical instruments. You don’t want an Icon that starts out as an “aid” to help one focus on Godly things to turn into an object of worship. As far as instruments go, you don’t want them to become the instrument being worshiped as well.

Calvin,

Just a quick note about icons. Orthodoxy views icons as “windows into heaven.” This is based on the sacramental view of the world. The Bible is more than a written record of what Jesus and the apostles said. The Bible does more than remind us mentally about God; the Holy Spirit inspires Scripture and for that God speaks to us in Scripture. Similarly, icons do more than make us think about Christ and the saints; icons make visible Christ’s invisible but real presence in the sanctuary.

I recommend you attend the Sunday worship at a local Orthodox church if you haven’t already. Observe the overall flow of the Liturgy (service) and take note of the role of the icon of Christ up in the front. For me the icon of Christ up in the front provides a visual focus; otherwise my eyes and mind will be wandering all over the church. As I listen to the liturgical prayers my spirit and my heart goes beyond the icon to Christ himself. I’ve never found myself thinking, “What an awesome, stupendous, amazing icon! It’s the most wonderful beautiful thing in the whole world. I just adore that icon!” For me the icon of Christ up front serves more as a springboard that takes me to Christ who invisibly present with us in the Liturgy. Having the icon also makes it practical to show reverence to Christ by bowing to him. If a church has no icon of Christ bowing to Christ becomes problematic. When I was a Protestant I usually thought of Christ up in heaven than down here with us, and when I read the Scripture passages about bowing down to God I interpreted them to mean that I do that mentally in my head or that I had to wait until the Second Coming.

This is getting to be more than a quick note! 🙂 I’ll stop here.

Robert

Excellent point. I’ve been “checked” before in service when after my mind started to wander, I caught sight of the Icon of Christ and was immediately brought back into focus – and humbled. His real presence really hits home with the Icon being there.

Robert, that’s a really good brief, concrete explanation of the role of the Icon and the Orthodox attitude toward it in the worship of Christ.

TҺanks fߋr fnally writing about >Early Jewizh Attitudes Тoward Images

– Orthodox Reformed Bridge <Loved it!

I realize my comment is very late in coming to the discussion but I would appreciate it if Robert or anyone from the Orthodox side could explain some things that have me very skeptical of some of the uses of icons that the Orthodox have as well as the reasoning that Bigham uses here by drawing upon Jewish custom.

First, let me start by saying that I do not have any objection towards artistic depictions of saints and/or people from the Bible. In fact, in my opinion such images enhance worship as they remind us of those who have gone before and they are at the same time visually engaging and beautiful to look at. Neither do I have any issue with kissing them or bowing to them if it is done out of reverence.

What I have always had an issue with is how I have heard/read Orthodox believers describe some of their uses of icons. (Forgive me if what I have heard is not acceptable Orthodox practice but rather a distortion of it by some people who merely do not know better.) I hear things to the effect that it is better to pray towards the icons rather than to not use them in prayer, and that there is some sort of special spiritual presence of the saint/Jesus in the icon that brings one closer to whomever is depicted in the icon (conversely, I do not have an issue with them being used a tool to remind us that Christ is always present, such as Robert and Jacob wrote in their comments above). Instead, when I read the earliest Christian writings (NT and early Fathers) I get the sense that the only way to enhance our spiritual connection to God is by obeying his commandments–partaking of the sacraments, being constant in prayer, abstaining from sexual immorality, building one another up in love, putting to death our sinful desires, and so on.

To me, saying there is a special presence of Jesus in an icon appears to come very close (or equivalent) to what the Israelites did with the golden calf at Sinai. The reason I say this is that the Israelites worshipped the golden calf as the god who saved them from the Egyptians. That is, they did not adopt a local pagan god, but were attempting to worship the divine being who had just supernaturally saved them. However, this worship was done in a form which was forbidden by the One who saved them! Thus it appears that the prohibition was not just there to prevent God’s people from worshipping pagan idols but also there to forbid them from using an object of anything that God had not expressly revealed his presence to be in continually (i.e. the Ark of the Covenant, and then later the Holy of Holies), or from any attempt to depict him–even though he had made his presence known through physical objects such as fires and clouds, and had appeared as a man to Abraham and Jacob. On its face this would lead me then to conclude that attempting to worship or pray to God through other objects is spiritually harmful. One might object and say that it was the fact that it was a cow that made it idolatrous, as God has never revealed himself in a cow. But he had revealed himself in the form of a man, fire and cloud in the OT, yet no exceptions are made for making an image of those things (I’ll talk about this more below).

Furthermore, from the reasons given in this article above, I do not see how ancient Jewish use of images can be used as support for such a use of icons. Firstly, because I don’t see Jewish use of images in Synagogues and in the Temple as being comparable to that of what Orthodox believers do. I.e., no praying/bowing toward the images, no talk of the special spiritual presence of YHWH in them, etc. As far as I know, Jews only did this towards the Holy of Holies because God said he was actually present there. From reading the New Testament and the earliest Church Fathers it seems that we can only safely conclude there is a special presence of Christ in the church (e.g. as Paul writes in Ephesians), in the Eucharist, and in any other clearly supernatural phenomenon such as the tongues of fire coming down at Pentecost. If this is the case, then why do Orthodox believers not bow towards a group of believers and pray towards them when they see them from a distance because they know Christ is present amongst them? For the Scriptures explicitly lay out that there is a special presence of Christ amongst his people. Is not the presence of Christ more worthy of worship than an icon is worthy of veneration?

Second, one only has to do a small amount of study of ancient Jewish customs (whether inside or outside of the Bible) to see that their religious practices could be all over the map, and that an unfortunately large number of them at any given time were syncretistic with their belief in YHWH and surrounding pagan practices. So even if the Jews used the images in the same way Orthodox do now, then one needs to show that this type of use was in line with the Torah. Therefore, I think the decoration of the Temple is a better standard by which to judge as that is the only thing we can be sure was sanctioned by God for use in worship, and in the temple the only depictions of living things are of general angelic beings (not specifically named ones or known individuals) and plants. Thus they appear to be there to instill a general sense of awe and to remind those in the temple of the reality of the angelic host that is with God and of the greatness of all that God has made. Despite this, explicit recognition or use of these images was never a part of worshipping God as icons of Christ are used today.

Third, YHWH did appear to people from the time of Adam to Daniel as a man yet I do not see any consistent depictions in Jewish art of these figures–and certainly none of them in the Temple. For example, he appeared to both Abraham and Jacob as a man, to Moses and the elders on Sinai as a man (Exodus 24), and to Joshua and others as the Angel of YHWH–which from what I can tell, is talked about as the same way as YHWH and I have heard many call these appearances as that of a the second person of the Trinity (though perhaps this interpretation is not taken in Orthodoxy?). Finally, we have Daniel’s (ch 7) vision of the Ancient of Days on the throne of heaven and ‘one like a son of man’ which appears to be the Father and the Son’s appearance to Daniel (see Alan Segal’s book, Two Powers in Heaven to see how there was a debate in Judaism about whether YHWH’s rule was carried out on earth by a second ‘power’–the son of man figure in Daniel 7–or if it was wrong to consider the second figure as God). Why is there no record of any Israelite ever depicting any one of these figures and/or using them as an aid in worship. For example, even with the painting in Dura Europos of the three youths in the furnace we see that they did not paint the fourth figure who appeared to Cyrus as ‘a son of the gods’. The furthest the paintings go is to show YHWH’s hands in the sky in the painting of the Israelites crossing the sea. This seems to establish that the Jews in this area were not at all comfortable with the full depiction of someone who may have been an incarnation of YHWH (beyond the hands at least–though those hands were there obviously not as a way of depicting an incarnation but only to symbolize YHWH’s supernatural intervention). I can think of no reason for this–especially since the surrounding religious cultures were not lacking in depictions of gods–other than their desire to obey the second commandment. In fact, it seems to me that the DE paintings show a strict conservatism against towards depicting YHWH in any way so as not to put any image of him in the eyes of those attending the synagogue.

Thus I don’t see how the Word made flesh leads to the necessity/benefit of using a purported image of Jesus to worship him, and I cannot see how one could use Jewish art as a way of supporting Orthodox iconography, for the instances and uses of images appears to be entirely different.

Rather, it seems to me that the Orthodox now treat the second commandment in the way that most Christians treat the dietary prohibitions that are found in the Torah. But for the removal of the dietary restrictions we have a clear saying from Jesus and an abundantly clear dream revealed to Peter. A breach of the second commandment was treated much more seriously than touching/eating unclean animals, yet for the doing away with the cleanliness laws we get two explicit statements in Scripture letting us know these don’t apply! In addition to this, I see no instances in the Old Testament or the first Christianity where depicting the incarnation of God as helpful in the worshipping experience of his people or even hinting that it is permissible.

Finally, I have a personal story as to why I am very uncomfortable with the way icons are used. My younger sister was adopted from Eastern Europe, and her relatives are part of the Orthodox church there. A few times they have sent her gifts, and one time they sent two small icons. She had grown up in a (loosely) Orthodox community but she says she did not become a Christian until a few years after being adopted (my family would identify as Reformed). From what I can remember of this time, she did not know what to make of Orthodox Christianity so she was not sure what to do with the icons when she got them and ended up putting them on her bedside table. The first night they were there she had terrible evil nightmares and was quite suspicious of the icons as a result so she gave them to my parents. My parents then decided they would throw them away as a precaution as they were naturally not comfortable with icons having grown up in Protestant circles. For some reason though my mother ended leaving them in a location out of sight near the bathroom my sister uses (who thought they had been thrown away). Then the next morning my mother asked my sister if she had nightmares again. My sister said that she had not, but that she had for some reason felt an awful presence of evil when she got near to the bathroom late the night before. The icons had been left out of sight and the place they were left is never a place anything gets left in our house. My sister had no idea they were there and would not have had any reason to suspect that they had been left there as she thought they had been thrown away, and nothing ever gets placed there in our house and there is no garbage can anywhere near there either. If she had only had nightmares then I would be more likely to suspect that the gifts had brought up past traumatic memories, but the event the second night left me with a strong impression that icons are used in ways that are not honoring to God and may have some direct evil consequences for God’s people as a result. Sometimes icons are compared to the holy and anointed vessels used in the Temple, but I cannot imagine such a vessel ever causing such an event as my sister experienced (I also don’t think this comparison is fair due to the fact that it is laid out in Scripture that vessels are supposed to be set apart for holy use). Additionally, the events of this experience corresponded very closely to an experience of a Catholic friend of mine who was storing some items in his bedroom closet of Buddhist friend of ours. These items included a number of idols, and he had been suffering horribly from nightmares ever since but never suspected anything and really had not thought of what might be the cause of the nightmares. Someone then pointed out the two things might be related and they prayed over his room and he stopped having those nightmares. Now I know that any object can be misused for purposes that are against God’s will, but I have never in my life heard of such stories where a Bible has caused such experiences of spiritual evil (I do realise that I am relying on my own anecdotal evidence here…)

I must close by saying that I do not want this to come across as me saying my personal experience trumps that of the Orthodox Church’s Tradition. But as an outsider who thinks the OT is clear in regards to the second commandment, and that the NT and early church shows no signs of abrogating the interpretation of this command by using images/objects to enhance a spiritual connection to God, I need reasons for thinking that the Tradition is good tradition and necessarily beneficial for believers. And I want reasons for this beyond that of “Christ promised the Holy Spirit would guide his church” or that a later ecumenical council accepted icons. For while the Holy Spirit does indeed guide the Church I cannot yet accept that all Tradition as defined in Orthodoxy is the best way of worshipping and is a direct result of the Spirit’s guidance, and I cannot see good historical reasons from the Bible and the early church for accepting or embracing all of the uses for icons that I have seen Orthodox people espouse.

Jonathan,

Many Protestants read the Second Commandment in isolation from the rest of the book of Exodus. In my article “The Biblical Basis for Icons” I point out that there are passages in the Old Testament where images were incorporated in the Tabernacle then later in the Temple. This failure to read the Second Commandment in light of the broader biblical context leads Protestants to misread and misunderstand Scripture. This is something that Reformed apologetics against icons has yet to address.

The intent behind the article on the use of images in Jewish worship is to point out that the Christian use of images has roots in the Old Testament. It was not something imported from the outside — from Roman and Greek paganism.

With respect to your observation holy living, consistent prayer life, partaking of the sacraments I would heartily agree that these deserve more emphasis than the kissing of icons. In the normal course of affairs the veneration of icons would be a minor thing in Orthodoxy. Unfortunately, the heresy of iconoclasm has forced Orthodoxy to give more attention and emphasis to icons than deserved. In other words, while icons are an integral part of Orthodox worship and spirituality, they are a minor aspect of it. But because icons are integrally linked to Christology, to deny icons is to undermine classical Christology hence the affirmation of icons made at the Seventh Ecumenical Council.

I would encourage you to visit an Orthodox worship service and observe the role of icons in the overall context of worship. I expect you will be pleasantly surprised as to how icons support the focus on Jesus Christ and the Holy Trinity. I would also encourage you to meet with an Orthodox priest for a one-on-one conversation. I think you will find it much more informative than what you read on the Internet.

In closing, I would encourage you the Second Comment, not by itself, but in the larger context of the book of Exodus and other books of the Old Testament. I would encourage you to become familiar with early church history, especially the controversies that gave rise to the Ecumenical Councils. Ask yourself if the Holy Spirit was indeed present guiding the early Church in fulfillment of Christ’s promise in John 16:13. If you disagree with the Orthodox understanding, then what is your understanding of how this verse was fulfilled in church history?

Robert

It seems to me that the key here is for us to meditate on the idea that, in the fullness of time, the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth. Jesus, the man-god, is the very personage whom the apostles saw with their own eyes, heard with their own ears, and touched as need may have been to dispel any disbelief of his incarnation or his resurrection. Once the fleshing of God had occurred, all minds were blown and all bets were off. God had now insinuated himself into man’s world and there was no more reason to consider himself to be spirit alone.

If they had had cameras at the time, Jesus’ photograph would be pasted on walls all over the world, and either venerated or spat at, depending upon the attitude of the person looking. Icons of Jesus in churches and homes are the visual contact that we have with the one who was made a man just as we are men, and they are so obviously relatable, like family photos sitting on a piano, that the looker is drawn effortlessly to pause and look, to reminisce, and to look beyond the photo to the person whom we know and love, and in such remembrance, to disregard the photo for the sake of the person himself.

Robert,

The difference between Solomon’s Temple and an Orthodox Church is that the Jews never worshipped or venerated their images. They did not kiss them or parade them about. In fact only the high priest could have anything to do with the Ark of the Covenant. When the Ark was carried about it was covered and hid from the people. The people sure weren’t admiring the Cherubim figures in the temple because they were not allowed in the temple. And religious art? Orthodox icons are a whole lot more than just religious art. Icons of Christ are not art, they are Christ and they are worshipped or venerated as such. Same with icons of the saints. Some of these icons even have bits of bone or skin embedded in them as Holy Relics. In some places entire corpses are venerated as Holy Relics! You simply cannot compare the palm trees and Cherubim in the temple with Orthodox icons.

Such a comparison is preposterous. Not the same at all. Not in intent or in execution. How John of Damascus goes from the prohibition of images to the Cherubim on the Ark to the worship of icons is an astounding and twisted bit of logomachy which really defies all logic because he never takes into consideration that the Cherubim and Ark and inside the temple were never even seen by the people. I don’t think any EO author or teacher I have read or heard even brings that up.

David,

I mentioned the Tabernacle and Solomon’s Temple because they are mentioned in Scripture. The use of images in these places of Old Testament worship is much closer to Orthodoxy than to Protestant churches that have just bare walls. The veneration of images in Orthodoxy is an extrapolation of what the Bible teaches about the use of images in Old Testament places of worship. What I find more striking is Protestantism’s iconoclasm which has no biblical justification. All too often what Protestants have done is to take the Old Testament polemic against syncretism with pagan idolatry and equate it to the use of images in Jewish worship. The two are two very different practices.

The Orthodox veneration of relics has some basis in Scripture. We read in 2 Kings 13:21 of a corpse being placed in the prophet Elisha’s tomb and upon contact with Elisha’s bones the dead man came back to life. This points to the sacred properties of the body of a deceased saint. So there is a biblical basis for something Protestants find strange and objectionable in the Orthodox veneration of relics of the saints. Having grown up in Hawaii I am familiar with the custom of showing respect to the departed ancestors and the importance of remembering them. It shocks and disturbs me that so many Protestants seem to forget about someone after they pass on, even prominent pastors or important longtime church members. In Protestantism the practice of remembering the dead is pretty much non-existent.

It’s okay for you to disagree with a Church Father like Saint John of Damascus, but I would ask you to be more respectful in your characterization of his understanding of Scripture. Please do not demean his interpretation of Scripture. Civility and mutual respect are important, especially in an interfaith dialogue between two religious traditions.

Robert

Robert

John of Damascene and subsequently all Orthodox polemics make the same huge leap in logic.

A. The 2nd commandment forbids images

B. But images are commanded to be made, i.e. the Cherubim

C. Therefore images are allowable just not false images

D. Christ is the true image of God

E. Therefore we not only can but must have pictures of him and venerate them

The leap being the equivocation of OT images with Orthodox icons and the argument that since Christ is the image of God we must make pictures and venerate them as witnesses to the incarnation and that this has a corollary in OT temple worship. It’s just nonsense because the people had very little part in OT temple worship aside from brining the sacrifices. I don’t think its uncivil to call his reasoning twisted because he is doing just that. He is twisting the meaning and use of OT images to justify the veneration of icons. OT images in the temples are not corollaries of Orthodox icons. The Ark and the Temple reflect heavenly realities and foreshadow Christ. Think of Isaiah 6 with the Cherubim covering God. And Jesus says in John 12:41 this was a vision of Himself! So the Ark with Cherubim covering it is a picture of Christ, Christ being the Ark of the new covenant.

In 1 Chronicles 28:19 we learn that David received the plans of the temple from God Himself same as Moses received the plan of the tabernacle from God. While Orthodox icons claim to be windows into heaven, the OT temple actually was. Book 2 of Ouspsensky’s “Theology of Icons” details how icons changed over the centuries and much was actually lost as to meaning and technique and even what subject matter was appropriate.

Interesting you bring up the incident with the corpse in 2 Kings. To make a normative doctrine out of something so extraordinary is dangerous. Ever hear of “grave sucking?” What it is, you lie on the grave of a minister who was fully anointed and you suck up his anointing. The incident with Elisha’s bones is given as proof of this practice. Needless to say this is a newer Pentecostal practice courtesy of Bill Johnson and his Prophetic Ministry school and I’m not sure how prevalent it is.

I would not say Protestants forget the dead. I live in a decidedly non majority Protestant nation and every Nov 1 the people go the grave yards and have picnics and leave offerings. I think its pretty abhorrent. But Protestants have memorials and graves. They just don’t venerate the dead or leave food and drink offerings at their graves. As David said of his dead son “But now he is dead, wherefore should I fast? can I bring him back again? I shall go to him, but he shall not return to me.” 2 Samuel 12:23

David,

Orthodox Christians do not engage in what you described as “grave sucking.” However, it is the practice of Orthodox Christians to visit the tomb of saints and ask for their prayers. This is more the exception as most churches do not have the bodies of saints buried there. What is more common is praying for the souls of the departed. This done several times a year. All this is quite Christ-centered, we turn to Christ and ask him to hear our prayers.

I’m curious. How do or how should Protestants honor their dead?

Robert

Robert,

I know the Orthodox do not engage in “grave sucking.” The point is that you are using the same verse in 2 Kings about Elisha’s bones to justify veneration of corpses that some Pentecostals are using to justify “grave sucking.” Both groups are taking a one time miraculous and extraordinary event and turning it into something normative and ordinary. I was specifically thinking of the veneration given to the corpse of St John the Wonderworker when I wrote about venerating corpses.

Protestants honour the dead in many ways not the least is erecting monuments to them. I hear the grave of Spurgeon attracts visitors every single day. So does the gaol in which Bunyan was held for 6 years. So does the Church where Edwards preached. Protestants have their own holy sites and relics wether they want to recognise it or not. Though I do not imagine they go there to ask for the dead to pray for them. In just two months I bet Wittenberg will be full of Protestant pilgrims for the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. (Will you be writing a 500th anniversary special article?)

Just because Protestants do not supplicate the dead does not mean they have forgotten their dead. Mementos, memorials, foundations, holidays, etc all serve that purpose. Ever been to Westminster Abby? It’s essentially a graveyard. A shrine to the many shining lights within Protestantism who are now dead. Funerals also serve the purpose of honouring the dead.

It seems as if you are equating not supplicating the dead with not honouring them? Is that so? How does not praying to or for the dead mean you don’t hour the dead? Seems like a huge leap of logic to me.

David,

There are two issues here: honoring the relics of the saints and asking the saints for their prayers. I cited the story of Elisha’s bones as biblical support for relics having sacramental qualities. I have been to the Russian Orthodox Cathedral in San Francisco where Saint John of San Francisco and Shanghai is buried. From the Orthodox standpoint of the communion of the saints and the biblical passage about the “cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 12:1) it is an honor to stand before the body of a great saint. For me John the Wonderworker is not far away but on the other side of the veil. Christ’s rising from the dead has shattered the gates of hell and his resurrection has destroyed the power of death. This opens up the possibility of fellowship between the church militant here on earth with the church triumphant up in heaven.

You mentioned Westminster Abbey, but keep in mind that it is part of the Church of England which seeks to mediate between the Protestant and Roman Catholic traditions. I don’t think it’s representative of Protestant Christianity. The Church of England has a memory of historic European Christianity that has been pretty much forgotten in the U.S.

You mentioned that Protestants honor the dead by holding funerals. From my experience, most funeral services are held outside the church at a local funeral home. Church funeral services are done but not the norm. From what I can see, these are done for prominent church members of pastors. However, in Orthodoxy it is expected that the funeral service be held at church with the prescribed services for all Orthodox Christians, lay and clergy. As a former Protestant, I find this difference striking. Orthodoxy takes a more hands-on approach to death. We have a prescribed tradition for how death is to be approached. Another striking difference is that Orthodoxy has memorial services for the dead. From what I know, Protestantism for the most part do not hold memorial services for the departed. After the funeral service is held, that’s it. Family members may privately visit the grave site of their late beloved but they do not ask the pastor to hold a memorial service for the loved one on the anniversary of their passing. In Orthodoxy, the memory and the presence of the departed is much more vivid than in Protestantism. In Protestantism, once you are buried and the funeral service is held, that pretty much takes care of things. I’m not saying that Protestants don’t care for the departed (they do), but for me the sense of the communion of saints confessed in the Apostles Creed was pretty much an abstraction until I became Orthodox. This imparts to Protestant Christianity a certain secular quality, a non-sacramental approach to the cosmos.

The Orthodox practice of asking the dead for their prayers is grounded in the reality of Christ’s resurrection. Furthermore, this practice is grounded in the fact that Christ’s resurrection was not a singular event that affected only one individual (Jesus) but a cosmic event that involves those who have joined themselves to Christ. The departed saints are now very much alive in Christ, standing before the throne of God and awaiting the resurrection. In the meantime they worship God day and night, and offer prayers on our behalf (Revelation 5:8). In Orthodoxy, there is a sense of fellowship between the Christians here below and the Christians up in heaven. In Protestantism, there is the sense that the two are not on speaking terms, that there is a great separation between the two that won’t be bridged until the future Second Coming.

To sum up, we remember the departed Christians and pray for them. We also honor the saints who faithfully served God and are now standing before the throne of God. You have your saints like Charles Spurgeon and John Bunyan, and we have ours like John the Wonderworker. Saints, Protestant or Orthodox, are exemplars of their tradition. As much as I admire Saint John of Shanghai and San Francisco, there is another American Orthodox saint I admire — Peter the Aleut, a teenage boy who suffered horrible torture and died – possibly in San Francisco – rather than deny his Orthodox Faith. On a recent visit to San Francisco, I visited the Roman Catholic mission (a possible site where Peter may have been martyred) and asked his prayers. This was a mini pilgrimage within a vacation.

Robert

Wow, really?

Yes, I do believe that the Spirit will guide the church in all truth as Jesus says in John 16. However, I think the Bible shows that the best way to test the truth is to compare what someone says to what is written in Scripture already. At this point I’d say I don’t have a good answer as to how this verse is fulfilled, but I am rather suspicious of Orthodox iconography as an instance of the working out of the Spirit’s guidance in Christ’s church. It makes me wonder if the Orthodox at times value the adherence towards traditions that arose in a way that unintentionally leads some to contravene a command of God. And yes, perhaps the best thing for me to do at this point is to try to observe learn more on my own of how icons play a role in the life of an Orthodox believer.

Now, some further clarifications/remarks about icons:

I do not believe that the OT bans images of holy people/things but rather bans idols. Now it seems to me an idol is an object that one prays to/worships. God makes it very clear that he does not inhabit any object but that at times he was specially present in fire, smoke, the Tabernacle, and the Temple, and also appeared in human form at various times during the OT. Thus it was completely appropriate for people to worship at these things/beings. For this reason I don’t understand how, as Lawrence writes above, that the Incarnation showed that “God had now insinuated himself into man’s world and there was no more reason to consider himself to be spirit alone,” and therefore it is good to pray/worship at images of Christ. There were multiple revelations of God in the OT that I listed above that showed this before Jesus.

The images in the Temple and on the Ark we’re not venerated, but God was unmistakably the center of worship. These cherubim were nameless and did not represent specific individuals in God’s presence but appear to represent generally the presence of the angelic host in YHWH’s heavenly throne-room.

Yes, God’s people have always been told to seek his face but this was never done through images, it was only done by following his commands, reading and meditating on his word, and by worshipping by facing towards the places where God had revealed his presence to actually reside.

The one time the Israelites did use an image to worship the God who rescued them from their bondage was at Sinai and they were nearly all killed because of their actions! There was no reason to face the image in worship as God had very clearly revealed his presence to be on the mountain in the cloud, and he was known to them as the Lord and Creator of all matter. Naturally, the Israelites often fell down in fear and reverence when his presence was felt by them but when this happened they rightly did not direct it at an object. God’s and Moses’ reaction at Sinai appears to be due to the fact that it was a mere object (even though it was one made out of religious devotion!), not for the fact that it was an object of the wrong type. I.e. he didn’t respond by saying “this is wrong because I have only revealed myself in physical things such as the burning bush, pillar of smoke, or a human figure as to Abraham and Jacob.”

As far as I can tell, from history and from personal experience/observation, idols in other religions are worshipped/prayed at as an image representing the god the worshipper is addressing. Those in other religions are all very cognizant of the fact that the spirit they are worshipping is beyond the image they face. I say this because that is exactly what I hear Orthodox people say to defend themselves–they are not worshipping the icon of Christ but Christ himself who they say is partially revealed to them by the icon. This sort of stance appears to be wholly unaware of the fact that idolatrous people believe the same thing about their idols and their gods–they don’t think the piece of stone, wood or metal is divine in and of itself either. Thus when a Council of God’s people purport to use images in what appears to be in contravention of such a clear and ancient command to protect against idolatry should we not naturally question its validity?

When I was growing up I knew next to nothing of Catholicism and Orthodoxy, but I had heard that the Catholics were idolaters who pray to their crucifixes and that the Orthodox have even more “forbidden images” that they worship(!). Later I heard that Orthodox have their images in order to pay respects to the dead and honor the memory of saints who have gone before them. This type honor sounds absolutely fine to me. It almost seemed to me to be a misunderstanding like that of what happened in Joshua 22 when the half tribe of Manasseh built an altar on their side of the river. The rest of Israel assumed it was for use as an altar (a very natural thing to assume!)–which was obviously forbidden. However, it was only built to be a witness and not for actual use as an altar, as God had made it very clear that only one altar was to be used. That altar was where God’s presence was–the Tabernacle. However, the deeper I dived into it the more Orthodoxy’s use of icons appeared to blur the distinction between honor and worship.

Orthodoxy’s use of icons thus brings to my mind what happened when John prostrated himself before the angel in Rev 22:8 (perhaps those knowledgable in Greek could advise on whether the Greek shows whether the angel was the object of religious affection or if he merely did it before the angel). The angel responds (v. 9) by saying “You must not do that! I am a fellow servant with you and your brethren the prophets, and with those who keep the words of this book. Worship God.”

John obviously was not worshipping the matter of which the angel’s form was composed, and neither was he worshipping a false god (which, from my experience seems to be how Orthodox people generally define idolatry). He knew there was only one God and He knew the risen Jesus and he presumably knew that the angel was not Jesus! Yet the magnanimity of the event caused him to prostrate himself before the angel as he felt God’s presence around him. In response, the angel appears to put himself on the same level as that of John and ‘his brethren the prophets’ and therefore makes it abundantly clear that he is completely unworthy of such a worship-like action. This appears to show that when a prophet of God encounters the presence of the living God he can be driven to such acts of physical and spiritual worship even towards persons or objects in whom God is not actually revealing himself as he did in Jesus (who is obviously worthy of all worship). Some say they like having crucifixes and icons of Jesus so they can have something to bow towards when they worship God. But to the best I can see the most proper response is to direct all of this devotion towards God in our minds, spirits and souls and by not intentionally facing any object or being as a conduit through which to encounter God until we truly encounter Jesus face to face. Therefore in this instance in Revelation this was best accomplished by John NOT prostrating before an angel. (Though as I said in my previous comment above, I would distinguish this from having other physical images such as crosses, Bibles or pictures present which may help to refocus ones mind while worshipping.)

Writing this has also made me wonder what sort of unanimity there was at the Seventh Ecumenical Council as to what worship/veneration/honor was to be given to icons? For example, pps. 11-12 of this book https://books.google.com/books?id=5sCqMrxtjBAC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22seventh+general+council,+the+second+of+Nicaea,+held+A.D.+787%22&lr=#v=onepage&q=&f=false

about the Council has the following quote:

“I receive, embrace, and give honorary worship to [the Saints’] holy and precious relics, in the confidence that I shall obtain sanctification from them; and in like manner I embrace, salute, and ascribe the worship of honour to venerable images, both of the dispensation of our Lord Jesus Christ, in that human figure which for our sakes He adopted, and of our immaculate Lady the holy Mother of God, and of the Godlike Angels; and of all the holy apostles, Prophets, Martyrs, and of all Saints.”

Did everyone talk of the images like that at the Council? Did everyone there agree icons deserved “honorary worship” (perhaps someone could clarify the meaning of this word in the original document)? Did they believe in a special presence of Christ in icons or give reasons for their believing in this type of presence? (I’m hoping to have this answered without reading that entire book!) I have not looked in depth into all of the earliest accounts of images in churches before this Council, but they do not appear to always talk of images in the same way as this Council does. Did they always give them “honorary worship” or at times did they “merely” honor the images as reminders of the saints and martyrs? And finally, does the Council give reasons for their stance by which we could deduce why their upholding of honorary worship of icons is different from what John did in Revelation 22 before the angel?

David, my understanding of idolatry is taken from Romans 1: loving the created thing more than the creator. I trust you do not have a problem with that since it is taken solely from Scripture.

But here comes the rub: the interpretation. Icons are not idols because we Orthodox honor the Holy Trinity alone when we venerate them. In fact, when I approach an icon, I Cross myself and say. “Glory to Thee O God, Glory to Thee.”. If I have any other prayers I add them after. We honor saints because they manifest God’s grace.

Icons can become idols but that only happens when God is forgotten and they become a thing in themselves. Of course that also happens with any other created thing too, even the Bible.

I have met people in my life who have made an idol out of the Bible but I would never infer from that all use of the Bible is idolatrous. Iconoclasm makes that illogical leap.

Unfortunately, Iconoclasm’s logical end is nothingess. It can seem worthy to get rid of all images to honor God alone, but once the images are gone we have to start destroying each other. Are we not made in the image and likeness of God?

That is what happened in Soviet Russia and what is happening today under Islam, in China and in the secular governments of the west. That is the nihilist dream for humanity in order to give birth to the Anti-Christ.

To simplify a bit, computer icons actually illustrate the reality of Christian icons. One uses the icon on the computer to access the program it represents and points to. You can get to the program other ways, but those ways are more difficult.

Nevertheless no one mistakes the icon for the program.

Thus with Christian icons as well except they allow us entry into the eternal Kingdom here and now.

The reason the Jewish images were not displayed publicly or used as we use icons today was because the veil of the Temple had not yet been torn asunder and Jesus Christ not yet raised from the dead. Big difference.

Christian icons, with each living person the ultimate example, exist because of the Incarnation, the Crucifixtion and Ressurection. They are literally washed in the Blood of the Lamb and clensed by the Holy Spirit.

“What God has cleansed call thou not unclean.”

But you prefer the incredible reductionism of an extremely narrow view of Sola Scriptura.

It grieves my heart. Why limit God and truncate His glory and deny His presence filling all things, resanctifying all that has been corrupted by our sins?

That is the Hope of the Gospel: “Behold, I make all things new”

BTW, I am not making an intellectual argument about ideas. I am testifying to what I have seen of God’s mercy and Grace, unworthy though I am. There is much, much more. Blessed be the name of the Lord.

Michael, you say it’s not idolatrous because you honour the Trinity, yet the Israelites we’re trying to honour the God who saved them from the Egyptians when they made the golden calf. They knew that the piece of gold had not saved them from the Egyptians as they saw it made before their very eyes and thus were obviously trying to worship the God who saved them through using the golden calf.

The Temple’s curtain being torn was done to show that humans can now approach God directly, does it not? I don’t see how it can be interpreted as making way for the images inside the Temple to be used as an object of worship as they were never used that way to begin with. Only God’s presence was worshipped but he was never shown to be specially present in the images but in the space.

I don’t think David or I am trying to deny God fills all things, but Orthodox seem to be saying that God especially fills icons. The ancient Israelites also believed God’s presence was everywhere (see Psalm 139 for instance) but they believed that the only place where God was specially present was where he clearly revealed himself to be present–the Tabernacle, Temple, and the times God appeared in human form or the burning bush etc. Now compare that to the NT. God is shown to be specially present in Mary when she conceives, Jesus, the fire at Pentecost etc. If Orthodox believe God is present everywhere why don’t they worship at the doormat when the walk in the door? Or the carpet or every tree they see when they walk outside? This is what does not make sense to me.

Jonathan, the veil of the temple was torn so that the communion between God and man could be more available. Not for individual reasons. The priesthood is still needed for sacrament.

The divide in understanding is the difference between a sacramental reality and a non-sacramental individualism.

There is a lot of evidence for the reality of the icons as windows into heaven but in a context of non-sacramental nominalism none of the evidence will make sense to you.

Looking at it from outside, Reformed Protestantism seems fundamentally iconoclastic. Orthodoxy is the opposite.

I have no understanding of iconoclasam. I have never been Reformed. So I am not the best person to talk to about it. I was received into the Church when I was 39 years old.

I had been longing for Jesus consciously for 19 years at that point. The first time I entered an Orthodox Church I was blown away by the icon of Mary, the Theotokos, with Jesus on her lap in prayer at the back of the altar. I suddenly felt welcome. Iconoclasm makes no sense to me. Neither does idol worship.

To me they both seem focused on appeasing a distant god out of fear although in different ways. That is my impression, not a condemnation of you.

A true story: my wife was received into the Church shortly after we were married. She had journeyed through many Christian denominations in her 60 years. Her first time in an Orthodox Church was when she came to my parish as we were courting. When she saw the icon of Christ Enthroned above the altar she was amazed. She has told me repeatedly(and anyone else who will listen) that that icon looks just like Jesus did when He came and comforted her as a little girl hiding from her abusive dad. Big chair and all. She is still in awe. Of course, wy wife is the oldest five year old I know, at least when it comes to approaching God. Her exuberence for God bubbles.

I could easily fill a small book of similar stories just from my own parish. You can also search for Our Lady of Cicero on line.

I really don’t know how else to say we don’t venerate icons because they are pictures replacing God. We venerate icons because of God’s presence through them–approached properly, with reverence and thanksgiving to God. We expect nothing nor look for anything from the icon itself. That would be idol worship. They are part of the multi-faceted beauty and glory of God.

“There is a lot of evidence for the reality of the icons as windows into heaven but in a context of non-sacramental nominalism none of the evidence will make sense to you.”

I know there is evidence for this, and (I think) I understand the Orthodox view of a sacramental reality, but I am just not sure it isn’t against what the Bible says in some ways. Jesus said that there will be some who do miracles in his name, yet Jesus will reply to them “I never knew you; depart from me you workers of lawlessness.” So signs and wonders alone aren’t enough to validate that something is from God. Furthermore, just because something has been associated with supernatural acts does not mean that we should worship/pray at that thing. This is why the angel rebuked John in Revelation as I wrote above. For is not the very presence of a living angel of God a greater window into heaven than an icon made by humans? Then if it was wrong to treat the angel that way, why is it not also wrong for us to treat icons in this way?

I don’t think an ecumenical council’s decision is enough to go against what the Bible teaches. And as I explained above, I don’t understand what the difference is between trying to worship God by bowing down to an angel, and trying to worship God by bowing down to an icon. The Jerusalem Council made their ruling based upon Jesus’ teaching, likewise the other ecumenical councils made their decisions based upon the Jesus’ and the Apostles’ teachings. If an ecumenical council goes against what the Bible has taught, how can we say they are being led by the Holy Spirit? Has not God given us both the Scriptures and the Church to guide us? If the Church looks like it is going against what has come before it, how can we say it is being led by God?

To use the analogy of the half-tribe of Manasseh in Joshua 22 again… there was absolutely nothing wrong at all with them building an altar to remind them of the reality of what/Who was at the Tabernacle. But if they started praying to this altar of theirs and then started using it to sacrifice to God, then it would have been a horrible sin! To me, this is what it seems the Orthodox Church has done. They have taken things which are to remind them of the heavenly reality, but then they have started to use them in a way which contravenes God’s commands.

Hi Jonathan,

I’m sure Michael will want to reply to your comment.

Thank you for continuing to engage the Orthodox viewpoint on icons. I was wondering if you have had the chance to talk face-to-face with Orthodox Christians about icons and the role of icons in their spiritual life? Let me put the question more bluntly: How many Orthodox Christians have you met with on this question? Without conversations with real flesh-and-blood people you are approaching the question of icons in a very cerebral, abstract fashion.

Based on what you just wrote, I’m not sure you quite grasped the Orthodox sacramental understanding of reality. In the last line of your comment you stated that icons are there to remind us of the heavenly reality but that is not the Orthodox understanding. For us, the icons make visible the heavenly reality of Christ and the saints who surround us. Think of it this way. There is a sacramental quality to the Bible – God speaks us through the Scripture. The Bible is more than a written record of men’s thoughts on God. We are touched in our spiritual core through the reading of Scripture. Likewise, baptism andHoly Communion are more than symbolic reminders; something happens when we participate in the sacraments of the Church. We are more than reminded of Christ, we encounter Christ in a very real way in the sacraments. Similarly, we are touched in our spiritual core when we pray to Christ before his icon. I often pray while I’m walking or while I’m doing my yard work. I don’t need to bring out my prayer books and my icons into the yard! God can hear us no matter where we are. But when I stand before an icon of Christ I find that my prayers have more focus, that I’m spiritually more in tune with Christ the risen Lord who fills heaven and earth.

It seems that you are worried that Orthodox Christians bow down to angels. Let me assure you, we don’t do that!

You expressed concern about Ecumenical Councils going against what the Bible has taught but what you’re really saying is that your interpretation of the Bible and that of the Reformed tradition differ from that of the early Ecumenical Councils. It really comes down to one interpretation versus another interpretation. In this blog I have sought to show that the Reformed tradition’s iconoclastic reading of the Second Commandment requires taking that passage out of context and reading it apart from the broader context of Scripture. So far I’ve yet to come across a well-reasoned response to my criticism that the Reformed argument is based on poor exegesis. While Scripture does not call for specific forms of devotion like the kissing of icons, the biblical witness is much more supportive of the use of images in places of worship than it does the Reformed tradition’s practice of walls devoid of images.

The value of the early Ecumenical Councils is that they represent the consensus of the Church Catholic on important matters of faith and practice. The bishops present at the Ecumenical Councils by virtue of their ordination have a direct historical connection to the Apostles. Reformed iconoclasm suffers from two serious flaws: (1) it does not represent Protestantism as a whole – some Protestants are accepting of the use of images in churches and (2) it lacks any historical link to the historic Church of the first millennium. Thus, Reformed iconoclasm is based on an ahistoric and idiosyncratic reading of Scripture that stands in defiance against the historic consensus affirmed by the Seventh Ecumenical Council at Nicea in 787. The danger of Reformed iconoclasm is that it separates one from the historic Christian Faith.

My advice to you and other Protestants who question the validity of icons is that you attend an Orthodox Sunday worship with two questions in mind: (1) Is the worship Christ-centered? and (2) Is Holy Trinity being worshiped and glorified?

Robert