Venerating the Icon of Saints Peter and Paul

A reader recently wrote:

My greatest struggle with Orthodoxy is the veneration of saints, angels, and Blessed Mary. In the Book of Revelations there is a scene that plays on 22:8 where John bows to an angel and the angel rebukes him. Typically, Roman Catholic and Orthodox say that he was rebuked for trying to worship the angel (not venerate). The problem though (in my view) is that is the Beloved Apostle. He devoted his life to the God of Israel and when Jesus came to Jesus the Messiah (also God). He wrote one of the four Gospels. He would not worship an angel. It seems to me that that was veneration that he was offering and not adoration, but he was still rebuked for bowing. I can’t see how John would commit idolatry and worship the angel. He would try to veneration though. So if we cant bow to angels how can we bow (in veneration) to images?

My response

I took a look at Revelation 22:8. The text says: “I John am he who heard and saw them. I fell down to worship at the feet of the angel who showed them to me . . . .” I also checked the Greek text and found that there were two verbs used here: “epesa proskunesai.” (ἔπεσα προσκυνῆσαι NA28) The first verb “epesa” takes the aorist past tense of “fall down” and the second verb “proskunesai” (to worship) takes the infinitive form indicating the reason or motive for the action. You are right that John would not want to worship an angel but the infinitive of intent for “proskunesai” indicates that that was what he had intended when he fell down. Basically, the physical act of bowing is not intrinsically wrong. What was wrong was the intent behind the bowing, that is, bowing as an act of worship. The basic problem with your argument then is that it fixates on the first verb and ignores or overlooks the second verb. This misreading of Revelation 22:8 is not good exegesis. In other words, Orthodoxy, which is open to veneration, is on much solid scriptural ground than Protestantism, which shuns veneration.

Bathsheba kneeling before David – painting by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

If we look at Scripture we can find instances where people bowed to show respect to another person. In Genesis 33:6-7, we read that Jacob’s wives and children bowed before Esau during the family reconciliation. In 1 Kings 1:16 and 23 (RSV), we read that King David’s wife, Bathsheba, and the Prophet Nathan bowed down before the king. Verse 16 says that Bathsheba “bowed and did obeisance to the king.” In the book of Acts, the Philippian jailer fell down before the Apostle Paul asking “What must I do to be saved?” Paul did not rebuke the jailer because the jailer was attempting to show respect to the man he earlier treated as a lowlife criminal.

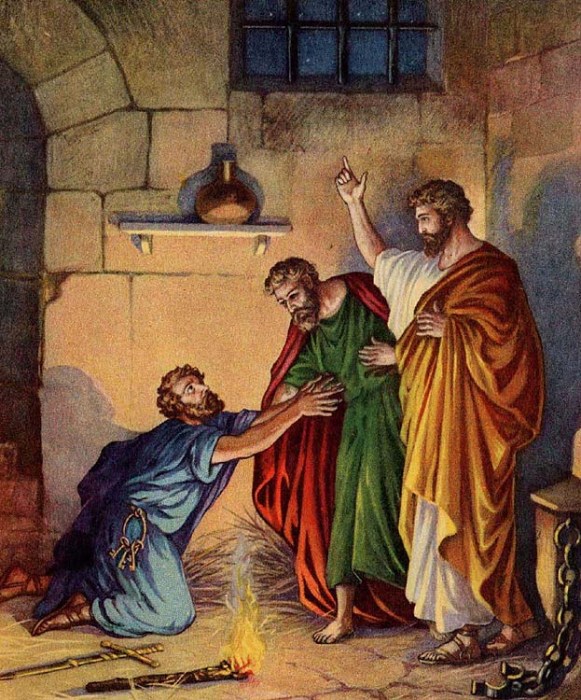

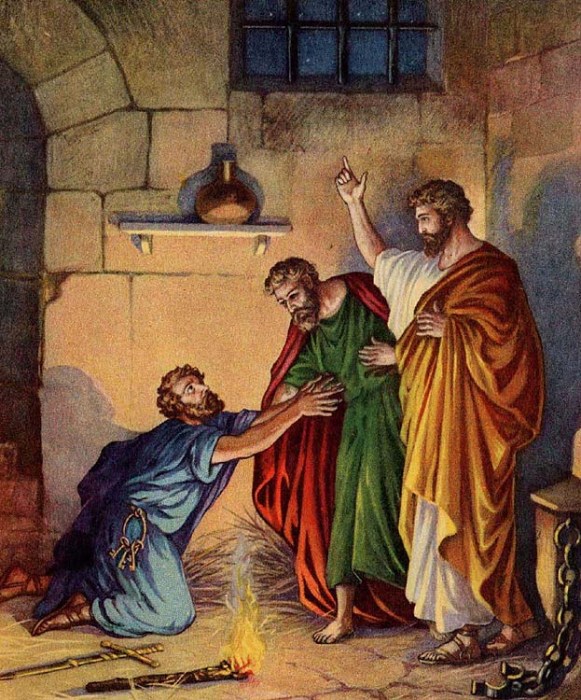

Philippian jailer kneeling before the Apostle Paul and Silas

Bowing in ancient times was a common practice with a range of meaning, from social courtesy to religious devotion. It seems that Protestantism has become hypersensitive to the physical act of bowing in their reaction against Roman Catholic medieval piety and in their attempt to purify the church.

The key difference between veneration and worship would be offering a sacrifice. This is what we find in Acts 14 when Paul and Barnabas learned to their horror that the citizens of Lystra were about to offer a sacrifice of oxen to them, believing Barnabas to be an incarnation of Zeus and Paul an incarnation of Hermes (Acts 14:11-15). Similarly, in Orthodoxy we may bow to show respect to Mary and the saints, but the core of the Liturgy is the Eucharist in which the bloodless sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood is offered to God alone. During the Liturgy the Orthodox faithful also offer up our whole lives to Christ our God, which is in accordance with Romans 12:1. The important thing to keep in mind is that the center focus of Orthodoxy is the worship of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Mary and the saints are peripheral. Not that they are ignored (as so often happens in Protestantism) but they are peripheral much like the supporting cast who surround the star of the show. Protestant spirituality can be likened to a Jesus-and-me spirituality. For many Protestants converting to Orthodoxy is a lot like a girlfriend who gets taken to her boyfriend’s home and meets all of his relatives. If she is serious about her relationship with the boyfriend, she is going to have to accept his larger family as well.

Bowing in Japan

The Protestant objection to bowing has disturbing cultural implications. If bowing is so intrinsically wrong, then Asians who become Christians are obligated to refrain from bowing to their parents, which would be taken as highly disrespectful and offensive. Furthermore, this position runs contrary to the Ten Commandments which enjoined honoring one’s father and mother—at least in the way Asians who apply it.

Protestantism’s Roots in Modernity

I suspect that the Protestant reservation about bowing stems from their being Western and their being modern. Modernity has resulted in a flattening of social relations and a break from traditional culture which assume hierarchical relations. This flattening effect can be seen in the Reformed tradition’s rejection of the episcopacy and their not addressing ministers as “Father.” This way of thinking is tragic and contrary to history. It is contrary to Christianity’s roots in Judaism and to the Tradition of the Church Fathers. Even early Protestant creeds used the language of hierarchy in social relations, even explicitly speaking about “inferiors and superiors.” See the Westminster Larger Catechism Q. 126 to Q. 133 which expounds on the Fifth Commandment.

In the eyes of Moderns, secularist and even Christians, all hierarchies are considered unjust and corrupting, and therefore to be scorned and done away with. Protestants have been at the forefront of espousing republicanism and the abolition of monarchies. Oliver Cromwell, a devout Puritan, led the movement to abolish the episcopacy in England and for a time headed the short-lived republican Commonwealth of England. This leveling influence can also be seen in Hawaii’s history where the leading haole (White) Congregationalist church (descended from the New England Puritans) openly supported the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy.

Protestantism’s new social dynamic had unintended consequences for faith and practice. Where the early Reformers retained a sacramental worldview and respected social hierarchies, later generations of Protestants reduced the sacraments to mere symbols, eliminated the office of the bishop, and expressly forbade the honoring of saints calling it sinful. Protestantism’s sola scriptura elevated the sermon to a position of prominence in the Sunday service and relegated the Eucharist to the periphery. But it did not end there; in recent years the sermon has undergone further changes. Where before the Protestant pastor would strive to give the unvarnished truth of God’s word based on careful exegesis, now the sermon has devolved into an inspiring or comforting message to please the audience. Many Protestant pastors have become religious entrepreneurs. Church members have become customers whose loyalty the pastor must retain in order to keep the religious enterprise going. This is religious commercialism where the customer is king and evangelism involves marketing a useful product. In this new religious context the Gospel—the Good News of Christ—is no longer the eternal truth of God but what suits the taste of the current market.

Holy Transfiguration Orthodox Church – Warrenville, IL

In contrast to Protestantism’s constantly evolving forms of worship is the Orthodox Church’s adherence to the historic forms of worship. A visitor to an Orthodox Sunday service will get to see the fourth century Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom. Orthodoxy’s liturgical style of worship retains a sense of dignity and hierarchical ordering long gone from from much of Protestantism. One notable example of this are the Small Entrance and the Great Entrance when the priest and the acolytes process around the interior of the church. Orthodoxy’s rubrics and protocols provide a much needed corrective to the casual informality of modernity.

Hierarchy and the Biblical Worldview

Hospital Hierarchy: Doctors, Residents, Nurses

How we worship God and how we live do matter. They are intertwined to an extent far more than we realize. Our understanding of society and human nature is impacted by our rituals and practices. The small act of bowing is consequential because it embodies the Orthodox ethos and worldview. To venerate the saints is to accept Orthodoxy’s hierarchical and sacramental worldview, where the heavenly realm overlaps with the earthly. The Protestant rejection of bowing reflects a flat, egalitarian approach to social relations, and a utilitarian, non-sacramental approach to nature.

Modern humanists of the Enlightenment who espouse egalitarianism don’t like the practice of veneration. They scorn it as “worshiping man,“ but they are wrong. It is not sinful to give honor to another human being but a practical acknowledgement of the way reality works. All men are not equal in every respect. Hierarchies do matter. There are hierarchical orders in our schools, in the workplace, in the military, in the hospitals, in our government. Why, then, do Protestants insist that churches be devoid of hierarchical order? We honor our graduates, our heroes, and those who made a contribution to society. Why not face up to the fact that some Christians are indeed worthy of our appreciation, esteem, and honor?

Protestants should also face up to the fact that according respect to our elders and those above us is part of the biblical worldview. In the Old Testament youths were exhorted to show respect to their elders.

Stand up in the presence of the aged, show respect for the elderly and revere your God. I am the LORD. (Leviticus 19:32; NIV)

In the New Testament, the laity was encouraged to honor the clergy.

Let the elders who rule well be counted worthy of double honor; especially those who labor in the word and doctrine.(1 Timothy 5:17; OSB)

Kissing Priest Hasnd

Becoming an Orthodox Christian involves not just learning and accepting a body of teachings, but also entering into a cultural ethos. For Protestant inquirers, it means relinquishing their rugged self-independence and accepting the Church as our Mother. An important mark of an inquirer’s readiness to become Orthodox is humility. Calling a priest “Father” can be difficult for some Protestant inquirers but it marks an important milestone in their journey to Orthodoxy. Calling a priest “Father” is an acknowledgment that the priest stands as a representative of Jesus Christ and has the awesome responsibility of pastoring Christ’s flock. At his ordination the priest is invested with the authority of the Orthodox Church and acts as a representative of the bishop, who stands in apostolic succession. In light of this, addressing a priest as “Father” is an act of showing respect to the Lord Jesus. It is also important to know that the priest’s authority is not arbitrary but is based upon and constrained by capital “T” Tradition. His authority is valid so long as he remains faithful to Tradition. The priority of capital “T” Tradition provides a much needed safeguard against arbitrary power and spiritual abuse.

Icon – All Saints

Hierarchy and the Coming Age

Hierarchical ordering is not just for the present age but also for the age to come. The Apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians described the coming age in which the resurrected saints will live in a glorified state.

All flesh is not the same flesh, but there is one kind of flesh of men, another flesh of animals, another of fish, and another of birds.

There are also celestial bodies and terrestrial bodies; but the glory of the celestial is one, and the glory of the terrestrial is another. There is one glory of the sun, another glory of the moon, and another glory of the stars; for one star differs from another star in glory. (1 Corinthians 15:39-41; OSB)

It is worth noting that there will be different grades of glory among the saints. This can be inferred from “one star differs from another star in glory.” They all belong to the same category of being but differ with respect to status.

When Orthodox Christians venerate the saints they are showing respect to their older brothers in the faith. Undergirding the spirituality of venerating icons is element of prayer, of relationality. When I venerate an icon I usually ask the saint to pray for me or for someone I have in mind. Without prayer, venerating icons become a superficial, perfunctory ritual. Underneath the venerating of the saints is a combination of affection and respect we show to our elder brothers and sisters in the Faith. This awareness of the importance of showing respect to older siblings or to older peers in school or the work place can still be found in Asian cultures. Present day Asians still have this appreciation for hierarchical order whereas this has largely disappeared in the West and in the U.S. where the culture of modernity has obliterated the old way of life.

Making Faith Real

Let me close with a personal observation that the Orthodox practice of bowing to show respect brought a physicality to my spiritual life that I did not experience as a Protestant. In many ways Protestantism is a cerebral religion and of which one unintended consequence is the mind-body split that weakens one’s spiritual development. The deep-seated individualism in Protestant spirituality has given rise to the plethora of denominations undermining their sense of belonging to the Church Militant. It has also led to Protestants suffering a spiritual disconnect with the Church Triumphant. This can be seen in widespread historical amnesia among Protestants and their refusing to venerate the saints. For me, becoming Orthodox has brought a deeper sense of belonging to the historic Church, a stronger sense of alignment with the biblical worldview, and an appreciation of integration into the cosmic order—the saints and the angels gathered before the throne of God as described in Revelation 7.

To sum up, the Orthodox veneration of the saints and the angels are not something added on to Christianity but deeply rooted in the biblical worldview and very much a part of the historic Christian Faith. The Protestant disavowal of the veneration of the saints marks a departure from the historic Christian Faith and created a new form of spirituality. Thank you for your question which has led me to a deeper appreciation of a “minor” practice within Orthodoxy. I hope that this response addresses your concerns and helps you to continue on in your journey to Orthodoxy.

Robert Arakaki

References

Douglas Cramer. “Call No Man Father?” Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese.

John S. Morrill. “Oliver Cromwell: English Stateman.” Britannica.com

“On Kissing the Priest’s Hand.” OrthoChristian.

W. Stanford Reid. “John Calvin: One of the Fathers of Modern Democracy.” Christian History Institute

Q. 126 to Q. 133 — Westminster Larger Catechism.

Recent Comments