Hagia Sophia – Church of Holy Wisdom

The historic Orthodox church building Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) recently received considerable international attention when Turkey’s highest administrative court gave the green light for the church’s conversion from a museum to a mosque. (Al Jazeera) The decision was met with widespread criticism or concern by political and religious leaders. (See References below: European Union, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Russia, Patriarchate of Constantinople and Patriarchate of Antioch.)

When I was a Protestant, I found myself deeply moved and inspired by Hagia Sophia. Unlike other Christian edifices, Hagia Sophia possessed a mystical beauty that haunted me. I knew that it was no longer a church building, that it had been seized by the Ottoman Turks and more recently had been converted into a museum. But even then, I found myself drawn to pictures of Hagia Sophia’s otherworldly interior that drew one’s attention heavenwards and glowing golden icons that spoke of another world beyond.

People sometimes boast that their church meet in a warehouse. I found myself wondering why they made such a big deal about that fact. Later I realized that the boast was an assertion of their being solidly Protestant without all the external decorations and rituals of Roman Catholicism. In other words, church architecture is not neutral but can be an expression of theology.

It seems that some Protestant circles intentionally promote a utilitarian approach to church buildings and to church ministries as well. This is similar to the error of Judas when he condemned the woman for wasting expensive perfume on the Lord when it could have been sold and the profit used for ministry to the poor (Mark 14:3-9). For the pragmatists the construction of ornate, beautiful buildings is a waste of money which could be spent on “more important things.” However, the lesson we draw from Scripture is that our God is a lover of beauty. Jesus praised the woman’s lavish anointing of perfume noting: “She has done a beautiful thing to me.” (Mark 14:6, RSV)

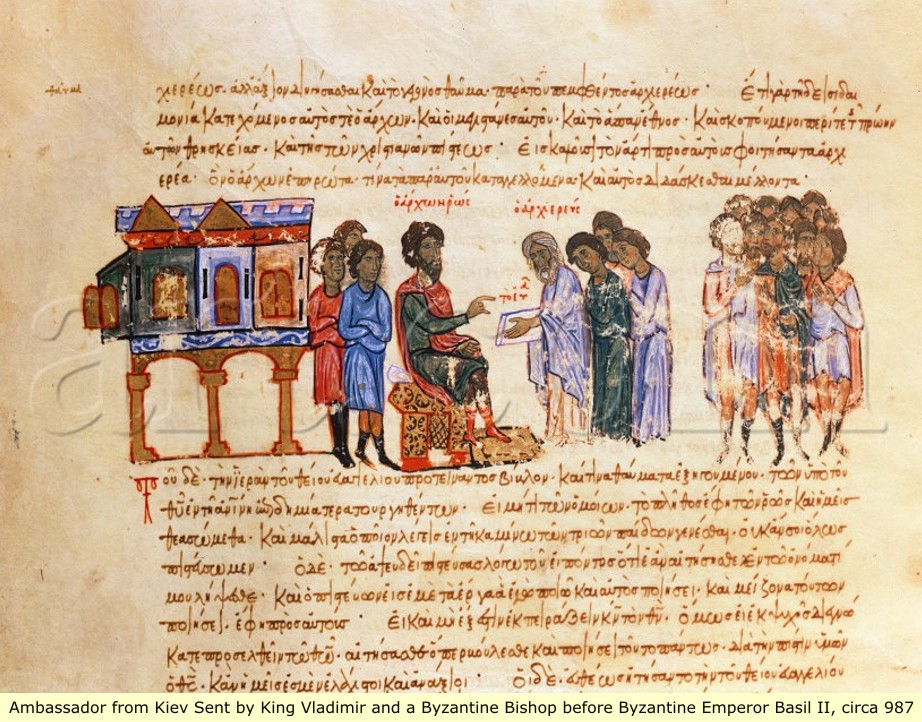

Byzantine Bishop Receiving King Vladimir’s Delegation

Hagia Sophia and the Conversion of the Slavs

The spiritual power of church architecture is demonstrated by the well-known story of how Hagia Sophia led to the conversion of the Slavs. The Primary Chronicle recounts how Prince Vladimir then a pagan was visited by representatives of the major religions of the time who spoke highly of their religion and denigrated the other religions. His counselors told him that it was natural for people to be biased towards their own religion so they gave him this advice:

You know, oh Prince, that no man condemns his own possessions, but praises them instead. If you desire to make certain, you have servants at your disposal. Send them to inquire about the ritual of each and how he worships God. (Primary Chronicle p. 110)

The envoys visited Germany, the Balkans, and Constantinople, observed the religious services then returned home. In their report they noted:

When we journeyed among the Bulgars, we beheld how they worship in their temple, called a mosque, while they stand ungirt. The Bulgar bows, sits down, looks hither and thither like one possessed, and there is no happiness among them, but instead only sorrow and a dreadful stench. Their religion is not good. Then we went among the Germans, and saw them performing many ceremonies in their temples; but we beheld no glory there. Then we went to Greece, and the Greeks led us to the edifices where they worship their God, and we knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendor or such beauty, and we are at a loss how to describe it. We only know that God dwells there among men, and their service is fairer than the ceremonies of other nations. For we cannot forget that beauty. (Primary Chronicle p. 111; emphasis added)

The conversion of the Slavs was a long time coming and many peoples and factors were at work. Even a casual perusal of the Primary Chronicle makes clear the human elements that accompanied Prince Vladimir’s conversion to Christianity: his geopolitical ambitions, his besieging of Kherson, and the heartbreak of Princess Anna being given away in marriage to seal Vladimir’s conversion (Primary Chronicle pp. 111-113). From a critical standpoint the envoys’ report on their visit to Hagia Sophia contains legendary elements but as J.M. Hussey notes there are “strands of truth” to the story (pp. 118-119).

This account of the conversion of the Slavs points to the power of holy beauty. In some branches of Christianity, apologetics is done by appealing to reason and logic alone. In contrast, Orthodoxy appeals not just to reason and logic but also to the very human and aesthetic experience of Orthodoxy worship: “Come and see!” (John 1:46)

Interior of Solomon’s Temple (artist’s depiction)

Architecture as Sacrament

Orthodoxy believes that all of creation is meant to be offered up to God and by grace transformed into sacraments (channels of grace). In Orthodoxy, church buildings are not viewed as merely functional shells but as manifestations of the kingdom of God on earth. Orthodox church architecture follows the heavenly prototype. This can be seen in the continuity between the architecture of Moses’ Tabernacle and Solomon’s Temple, both which were laid out in great ornate detail in the Holy Scripture of the Old Testament and imitated in Orthodox church buildings today.

There is in Orthodoxy a tradition regarding church architecture. It is expected that the church building will face east and that the interior layout will consist of the narthex, nave, and sanctuary (the altar area). Every Orthodox church has an iconostasis or icon screen. It is expected that the roof of the nave or middle area where the faithful gather will have a Pantocrator icon. This particular icon depicts Christ as the Pantocrator or All Ruling One. Upon completion the church building is consecrated much like Moses’ Tabernacle (Exodus 40) and Solomon’s Temple (2 Chronicles 5). Once consecrated an Orthodox church cannot be used for secular functions.

Orthodoxy’s approach to church architecture stands in radical opposition to Protestantism’s understanding of church buildings as intrinsically neutral and sacredness being contingent on the purpose of the activity. Thus, some Protestant church buildings after a worship service may be used to hold a town hall meeting. Many Reformed and Evangelical churches are marked by austere, minimalist interiors. This stems from the belief that spiritual beauty is interior and best expressed through hymns or preaching. Reformed churches that seek to manifest spiritual beauty through visual arts and church architecture are more the exception than the rule. See my earlier article: “Images Inside Reformed Churches.”

Remembering Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia is much more than an architectural marvel. It was designed, constructed, and consecrated for the worship of the Holy Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It was here that the Eucharist was celebrated, where “heaven strikes earth like lightning.” [#1] It was where one of the greatest preachers of all time—John the Golden Mouth (Chrysostom)—preached the Gospel. Even when it fell into the hands of the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Hagia Sophia still retains a Christian character and a haunting and holy beauty. Its beauty has haunted Orthodox Christians and we mourn the loss.

Orthodoxy’s mourning over the loss of Hagia Sophia resonates with Scripture. The Old Testament records the Israelites’ mourning the loss of Zion and their hope for the rebuilding the Temple.

When you rise up, You shall have compassion on Zion,

For it is time to have compassion on Zion,

For Your servants took pleasure in her stones,

And they shall have compassion for her dust.

And the Gentiles shall fear the name of the Lord,

And all the kings of the earth Your Glory;

For the Lord shall build Zion,

And He shall be seen in His Glory.

(Psalm 101 (102), OSB; emphasis added)

Psalm 50 (51), which is particularly beloved by Orthodox Christians, can be read as prophetically calling for the rebuilding of Zion.

Do good, O Lord, in Your good pleasure to Zion,

And let the walls of Jerusalem be built;

Then You will be pleased with a sacrifice of righteousness,

With offerings and whole burnt offering;

Then shall they offer young bulls on Your altar.

(Psalm 50 (51), OSB; emphasis added)

There are people today who have hope that Hagia Sophia will one day be restored as a place of Christian worship. It would be a miracle but with God all things are possible.

1500s — Islam’s inroads into Europe circa 1529 Siege of Vienna

Geopolitics and Hagia Sophia

Turkey’s president Recep Erdogan defended the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque as Turkey’s “historical and sovereign right.” Many Muslims greeted the news of Hagia Sophia’s conversion into a mosque with joy. This joy stem from the fact that for Muslims Hagia Sophia is a war prize obtained during Islam’s centuries long military expansion into Europe. Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, thirty years before Martin Luther was born. Protestants often overlook the fact that Luther and Calvin lived in a period when Islam was encroaching on Europe’s eastern borders. Luther wrote On War Against the Turk (Kriege wider die Türken) in 1528, shortly after the capture of Buda (modern day Budapest, the capital of Hungary) and during the siege of Vienna (the capital of modern-day Austria) (See Forell 1946). Older Americans, who remember seeing Julie Andrews in the movie Sound of Music, might want to reflect that Vienna could have become a Muslim city if history had taken a different turn. Protestantism’s encounter with Islam has been largely tangential in comparison with Orthodoxy which had centuries of experience of living under Muslim rule.

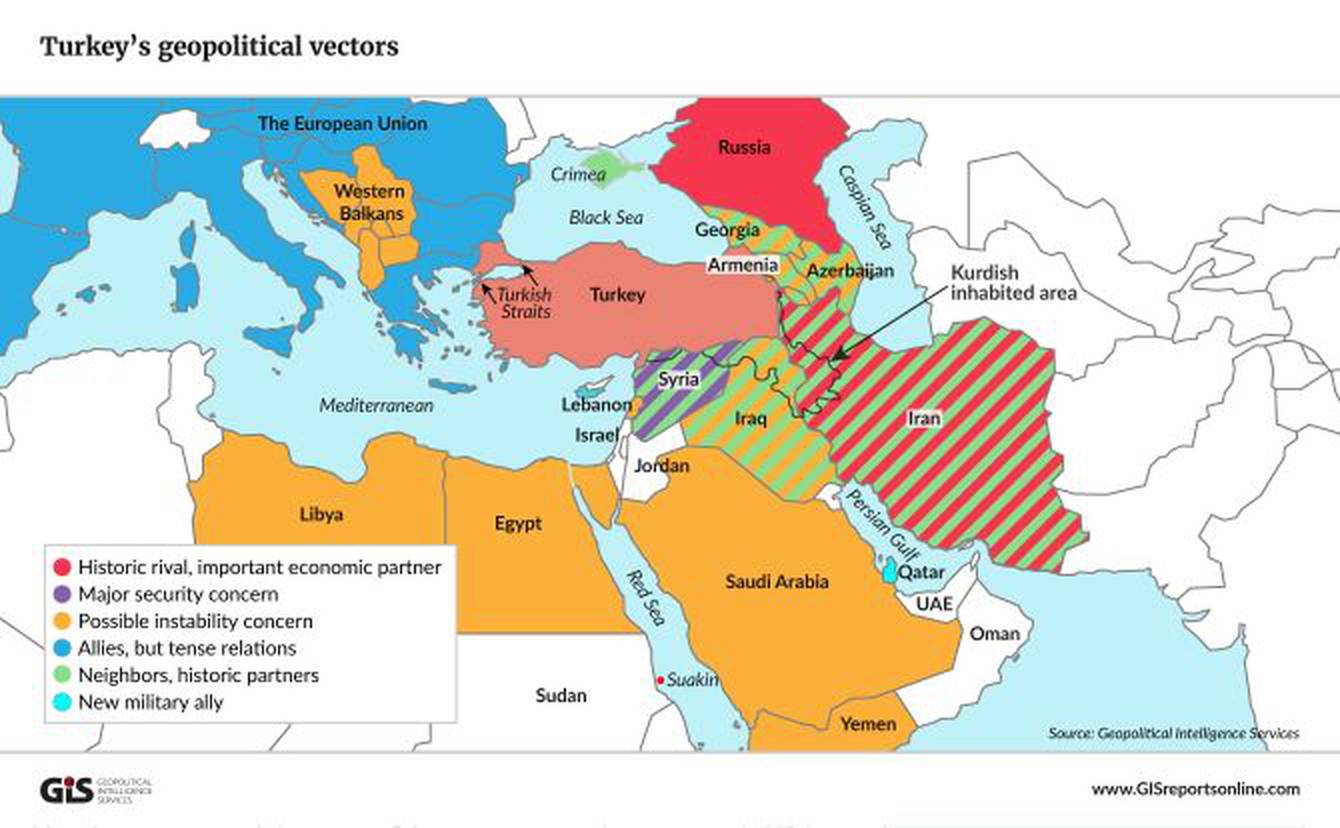

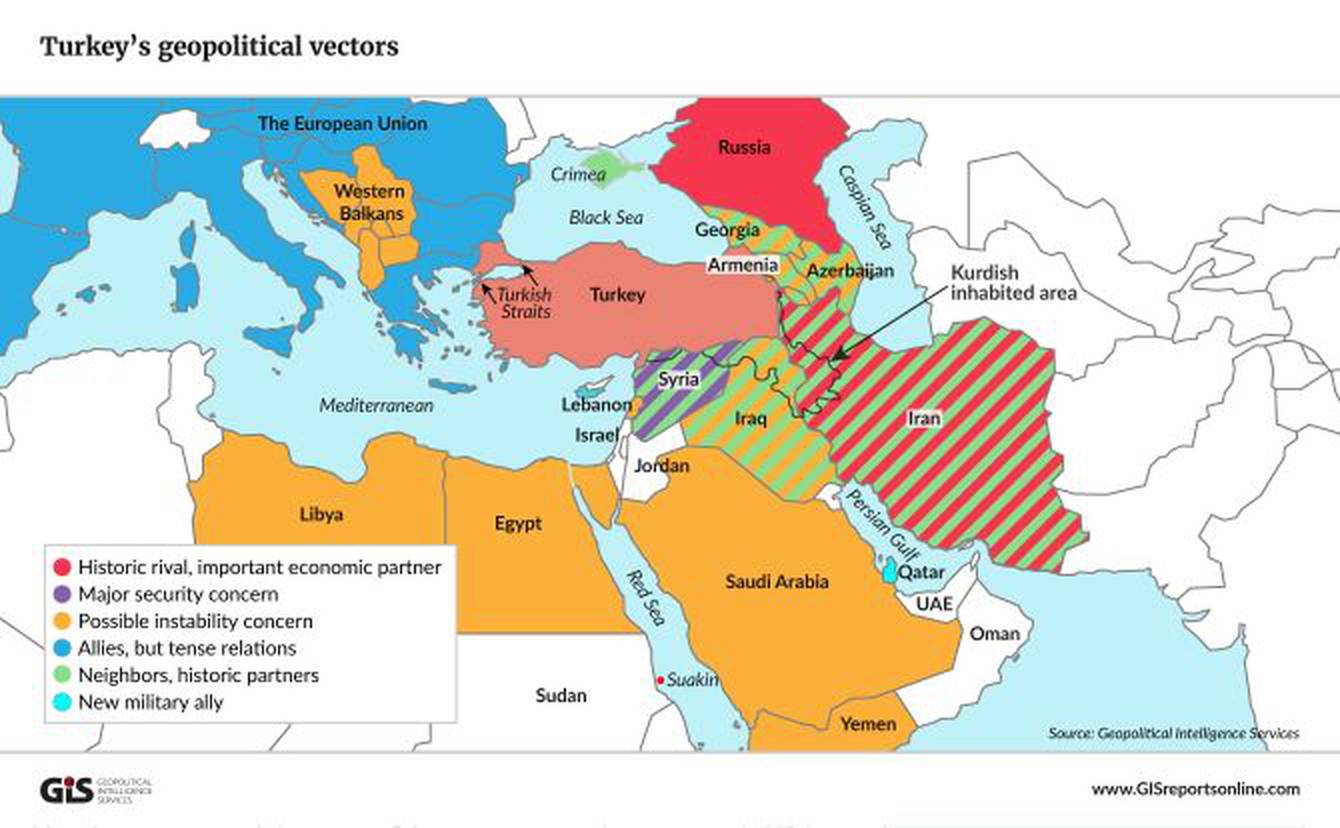

Today — Turkey’s Current Geopolitical Context

The recent developments in Hagia Sophia should not be viewed as a minor religious kerfuffle, but as fraught with geopolitical implications. Hagia Sophia can be said to mark the point where three major political-religious tectonic plates converge and press against each other: Western Europe’s republican secularism, Russia’s Orthodox Christian nationalism, and Turkey’s Islamic nationalism. This notion has been anticipated by Samuel Huntington in his controversial 1993 Foreign Policy article “The Clash of Civilizations?” At present Turkey is a candidate nation to the European Union, however, the recent decision to convert Hagia Sophia into a mosque has been condemned by the EU’s Foreign Affairs Council and could undermine Turkey’s path to EU membership.

Hagia Sophia’s conversion from a museum into a mosque represents a major setback for Turkey’s official Kemalist secularism. The decision points to the growing influence of a religious nationalism which seeks to replace the secular state with one that operates in partnership with the majority religion of Islam. Modern-day Turkey emerged following Word War 1 and adopted Kemalist secularism in 1928. In other words, Turkey’s secularism is relatively recent and not well established. A similar phenomenon has been taking place in Turkey’s neighbor to the north, Russia. In the wake of the collapse of Communism in 1989, Russia has been actively reclaiming its Orthodox Christian heritage. Instead of opting for Western secularism, Russia has chosen the path of religious nationalism. The Patriarchate of Moscow has been actively extending its presence internationally in recent years. Patriarch Kyril of Moscow has been outspoken in his criticism of Western Europe’s pursuit of secularism. In contrast, the Patriarchate of Constantinople has become a shrunken shadow of itself. Patriarch Bartholomew now presides over a few city blocks in Istanbul, the Phanar (Fener) district. It is telling that there are Greek Orthodox parishes in America that have more Orthodox members than in Istanbul (Constantinople) today. It is plausible to surmise that the Patriarch of Moscow with the backing of the Russian government will take a leading role in shaping the future of Hagia Sophia. The real conflict in world politics may not be democracy versus authoritarianism, but rather the rivalry between secularism and the various religious nationalisms. The partnering of religion and politics can also be seen in Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and the Reformed Church of Hungary, and in Poland’s Law and Justice Party which is closely allied with the Roman Catholic Church. While Turkey’s recent decision may stir up religious sentiments, official political reactions so far has been rather muted. See Hussain’s and Suchkov’s articles below in References.

Architecture as Evangelism

Hagia Sophia is more than just a building. This building changed the course of history. World history would be quite different if Russia had adopted a different religion. But even more than the church building, it was the celebration of the Liturgy that converted the Slavs. The divine glory radiating from the Liturgy filled Hagia Sophia and illuminated the hearts of those present. What happened in Hagia Sophia in 987 when Prince Vladimir’s envoys attended the Liturgy is still happening today. Like the early Slavs, many people today have attributed their conversion to Orthodoxy to their experience of the Liturgy. If one visits an Orthodox church service today, one can catch a glimpse of the heavenly worship like that offered when Hagia Sophia was a Christian church building. On a typical Sunday Orthodox churches still use the ancient Liturgy of John Chrysostom, which he celebrated in the fourth century. Orthodox churches today have icons of Christ and the saints similar to that seen in Hagia Sophia. Even today in the twenty-first century one can hear ancient Christian hymns like “Joyous Light” (Phos Hilaron), “Only Begotten” (Monogenes), or the Trisagion Hymn (Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal). Every year on Easter Sunday (Pascha Sunday) the Orthodox Church celebrates Christ’s Resurrection by reading out loud John Chrysostom’s classic Easter sermon just as he did in Hagia Sophia. Hagia Sophia’s holy beauty lives on today in Orthodox churches around the world. To those who are intrigued by Hagia Sophia’s holy beauty and curious about the Orthodox Faith, we say: “Come and see!”

Robert Arakaki

References

Al Jazeera. “Muslim prayers in Hagia Sophia for first time in 86 years.” Al Jazeera, 24 July 2020.

Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America. “Statement on the Tragic Conversion of Hagia Sophia from Museum to Mosque.” 10 July 2020.

Robert Arakaki. “Images Inside Reformed Churches.” OrthodoxBridge, 7 March 2020.

Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor, translators and editors. Primary Chronicle. Laurentian Text (986-988). The Mediaeval Academy of America. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Ecupatria.org. “Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew About Hagia Sophia.”

Herald Malaysia. “Bartholomew I slams the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque, says it offends Orthodox identity, history and culture.” Herald Malaysia Online, 14 September 2020.

Shahid Hussain. “Deconstructing Russia’s Response to the Hagia Sophia.” ModernDiplomacy.eu

European Parliament Think Tank. “Hagia Sophia: Turkey’s secularism under threat.” 24 July 2020.

Geraldine Fagan. “Political Christianity in Orbán’s Hungary.” The Budapest Beacon, 3 April 2018.

George W. Forell. “Luther and the War Against the Turks.” Concordia Theological Monthly. September 1946.

Samuel P. Huntington. “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Policy (1993) reprinted 2013.

J.M. Hussey. The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire. Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK.

Frederica Mathewes-Green. At the Corner of East and Now: A Modern Life in Ancient Christian Orthodoxy. New York, NY: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam. [#1 – This is the source for the phrase: “heaven strikes earth like lightning.”]

Prince Michael of Liechtenstein. “Turkey has the right to protest its national interests.” Geopolitical Intelligence Services.

Orthodox Church. “Orthodox Patriarch of Moscow – West is Making a Mistake.” YouTube video [4:40]

Michael R. Pompeo. “The Status of Hagia Sophia.” U.S. State Department, 1 July 2020.

Rob Schmitz. “As An Election Nears In Poland, Church And State Are A Popular Combination.” NPR 12 October 2019.

Maxim A. Suchkov. “Why did Moscow call Ankara’s Hagia Sophia decision ‘Turkey’s internal affair’?” Middle East Institute.

Mr. Whalen (Suffern HIgh School). “1529 C.E. – Siege of Vienna.”

Recent Comments