Did John Calvin believe in the “Fall of the Church”? That is, did he believe that the early Church apostatized from Apostolic doctrine and worship, and that true Christianity was not restored until the Protestant Reformation? The “Fall of the Church” is widely held among Protestants but some of our readers deny that Calvin held this view calling it a “canard.”

Did John Calvin believe in the “Fall of the Church”? That is, did he believe that the early Church apostatized from Apostolic doctrine and worship, and that true Christianity was not restored until the Protestant Reformation? The “Fall of the Church” is widely held among Protestants but some of our readers deny that Calvin held this view calling it a “canard.”

Part I. The BOBO Theory

Fuller Seminary professor and missiologist Ralph D. Winter noticed that many Evangelicals are under the impression that Christianity “Blinked-Out” after the Apostles and then “Blinked-On” with the Protestant Reformers.

. . . “BOBO” theory—that the Christian faith somehow “Blinked Out” after the Apostles and “Blinked On” again in our time, or whenever our modern “prophets” arose, be they Luther, Calvin, Wesley, Joseph Smith, Ellen White or John Wimber. The result of this kind of BOBO approach is that you have “early” saints and “latter-day” saints, but no saints in the middle.

Winter noted that this view has resulted in Protestants having little interest in the one thousand years of church history before the Reformation because nothing spiritually important was happening between the New Testament church and the 1500s. Winter wrote about the negative effect this had on Protestants:

But this only really means that these children do not get exposed to all the incredible things God did with that Bible between the times of the Apostles and the Reformers, a period which is staggering proof of the unique power of the Bible! To many people, it is as if there were “no saints in the middle.”

The BOBO theory is crucial to Protestantism’s self understanding. Protestants believe that after the calamitous “Fall of the Church,” the Reformation marked a return to the early Church – the way it was meant to be. Without this justification, the Reformation would be a schismatic deviation. Sometimes one is presented with a more subtly nuanced version that allows for a small continuing “Remnant Church” present throughout church history that held on to the True Faith – of course assumed to be more or less Protestant. The problem with this view, aside from the lack of historical evidence, is that this supposed historic “Remnant” existed independently of any historically recognized Church be it Orthodox or even Roman Catholic.

Did Calvin Hold to the BOBO Theory?

In “Necessity of Reforming the Church” Calvin made reference to the “primitive and purer Church” (p. 215). In his Institutes Calvin saw icons, altars, vestments, ritual gestures, and other decorations as signs of the early Church’s decline and degeneration.

First, then, if we attach any weight to the authority of the ancient Church, let us remember, that for five hundred years, during which religion was in a more prosperous condition, and a purer doctrine flourished, Christian churches were completely free from visible representations. Hence their first admission as an ornament to churches took place after the purity of the ministry had somewhat degenerated. I will not dispute as to the rationality of the grounds on which the first introduction of them proceeded, but if you compare the two periods, you will find that the latter had greatly declined from the purity of the times when images were unknown. (Institutes 1.11.13, p. 113; emphasis added)

Calvin also traced the fall of the church to the emergence of liturgical worship, something that commenced soon after the original Apostles passed on. Calvin wrote in the Institutes:

Under the apostles the Lord’s Supper was administered with great simplicity. Their immediate successors added something to enhance the dignity of the mystery which was not to be condemned. But afterward they were replaced by those foolish imitators, who, by patching pieces from time to time, contrived for us these priestly vestments that we see in the Mass, these altar ornaments, these gesticulations, and the whole apparatus of useless things. (Institutes 4.10.19, p. 1198; emphasis added)

In this passage we find a succession of: (1) “the Apostles,” (2) their second generation “immediate successors,” and (3) the subsequent generations of “foolish imitators.” What Calvin is asserting here is that the Eucharist underwent considerable change shortly after the passing of the Apostles resulting in the “Fall of the Church.” That all this happened within a few decades or in the first century after the Apostles’ repose raises serious questions about Calvin’s understanding of post-Apostolic Christianity. Calvin here is implying that the Apostles’ disciples disregarded Paul’s exhortations to “preserve” and “guard” the Faith “with the help of the Holy Spirit” (see 2 Timothy 1:14). This alleged “Fall” raises serious questions about the sincerity of the Apostles’ disciples and about the Holy Spirit’s presence in the early Church. This is not a small claim but very serious accusations!

We have here two different versions of the “Fall of the Church”: (1) an immediate Fall right after the passing of the original Apostles (Institutes 4.10.19) and (2) a later Fall after the first five centuries (Institutes 1.11.13). This inconsistency makes it hard for a church history major like me to ascertain when the “Fall” took place, who instigated the “Fall,” and what was the driving force behind the “Fall.”

The Blinked-Out, Blinked-On trope is especially evident in Calvin’s essay “The Necessity of Reforming the Church”:

This much certainly must be clear alike to just and unjust, that the Reformers have done no small service to the Church in stirring up the world as from the deep darkness of ignorance to read the Scriptures, in labouring diligently to make them better understood, and in happily throwing light on certain points of doctrine of the highest practical importance. (“Necessity” pp. 186-187, cf. p. 191; emphasis added)

We maintain to start with that, when God raised up Luther and others, who held forth a torch to light us into the way of salvation, and on whose ministry our churches are founded and built, those heads of doctrine in which the truth of our religion, those in which the pure and legitimate worship of God, and those in which the salvation of men are comprehended, were in a great measure obsolete. (“Necessity” pp. 185-186; emphasis added)

Therefore, from the evidences above it is clear that Calvin did in fact hold to the BOBO theory of church history. Orthodox theologians and historians can in many ways agree with Calvin about the Roman Church’s decline. However, where many Orthodox view Rome’s decline as having occurred after the Great Schism of 1054, Calvin viewed the “Fall of the Church” as having occurred during the time of the Ecumenical Councils when Rome was in communion with the other patriarchates. This is something Orthodox Christians would find problematic. Orthodoxy believes that it has faithfully kept and preserved Apostolic Tradition for the past two thousand years and because it never suffered a “Fall” is the same Church as the early Church.

Calvin’s Dispensationalism

Calvin’s understanding of church history as discontinuous marked by ruptures is not all that anomalous. One sees a similar understanding in Calvin’s view of the relationship between the Old and New Covenants. He wrote:

For if we are not to throw everything into confusion, we must always bear in mind the distinction between the old and new dispensations, and the fact that ceremonies, whose observance was useful under the law, are now not only superfluous but absurd and wicked. When Christ was absent and not yet manifested, ceremonies by shadowing him forth nourished the hope of his advent in the breasts of believers; but now they only obscure his present and conspicuous glory. We see what God himself has done. For those ceremonies which he had commanded for a time he has now abrogated forever. (“Necessity” p. 192; emphasis added)

The problem with this statement is that it is unbiblical. It contradicts Matthew 5:17 where Christ taught that he did not come to abolish (abrogate) the Law but to fulfill it. With the New Covenant came a new priesthood based on Christ’s priesthood and a new form of worship based on Christ’s sacrificial death on the Cross. Here It seems is the root cause of Calvin’s mistake – he tragically transposed the Protestants’ controversy with Roman Catholicism onto the early Church.

Part II. The Historical Evidence

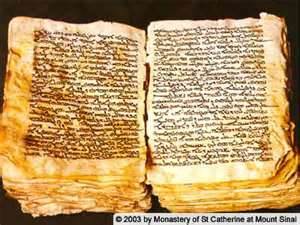

Calvin’s belief that the early church fell away from the Apostles’ teachings can be tested by examining the earliest Christian writings with respect to: (1) the Eucharist, (2) the use of icons in worship, (3) the Gospel Message, and (4) church government (the episcopacy). We will be using the following writings: (1) the Didache (c. 90-110), (2) the letters of Ignatius of Antioch (d. 98-117), (3) Justin Martyr’s Apology (d. 165), and (4) Irenaeus of Lyons’ Against Heresies (d. 202). These comprise the earliest Christian writings outside the New Testament and thus give us valuable insights into the faith and practices of the post-Apostolic Church and allow us to ascertain the degree of continuity in faith and practice.

The Eucharist

One way of testing Calvin’s “Fall of the Church” theory is by examining early Christian worship. One feature that immediately stands out is the importance of the Eucharist for the early Christians and their sacramental understanding of the Eucharist.

When I was a Protestant one thing I always heard at the monthly Holy Communion service was the pastor emphasizing that the bread and the grape juice were just symbols. So when I read the early church fathers I was struck by the fact that none of the church fathers taught that the bread and the wine were just symbols. As a matter of fact, they taught something quite different. Ignatius of Antioch referred to the Eucharist as the “medicine of immortality (Letter to the Ephesians 20:2). His belief in the real presence can be found in another letter.

I desire the “bread of God,” which is the flesh of Jesus Christ, who was “of the seed of David,” and for drink I desire his blood, which is incorruptible love. (Letter to the Romans 7.3; emphasis added)

Belief in the real presence can also be found in Justin Martyr.

For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh. (The First Apology 66; emphasis added)

Another early witness to the real presence in the Eucharist is Irenaeus.

When, therefore, the mingled cup and the manufactured bread receives the Word of God, and the Eucharist of the blood and the body of Christ is made, from which things the substance of our flesh is increased and supported, how can they affirm that the flesh is incapable of receiving the gift of God, which is life eternal . . . . (Against Heresies 5.2.3; emphasis added)

The Eucharist was central to early Christian worship and theology. In the early church to deny the real presence in the Eucharist was to commit heresy. Ignatius of Antioch wrote regarding the heretics:

They abstain from Eucharist and prayer, because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ who suffered for our sins, which the Father raised by his goodness. (Letter to the Smyrneans 7.1; emphasis added)

As an Evangelical I was struck by the fact that it was the heretics who denied the real presence in the Eucharist. Just as significant is Ignatius’ insistence that the Eucharistic celebration is integrally linked to the office of the bishop. In other words, early church government was episcopal, not congregational!

Be careful therefore to use one Eucharist (for there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup for union with his blood, one altar, as there is one bishop with the presbytery and the deacons my fellow servants), in order that whatever you do you may do it according to God. (Letter to the Philadelphians 4.1)

As an Evangelical in a congregationalist denomination I was unsettled by the fact that modern Evangelicalism was much closer to the early heretics than they realize. This started me thinking: Was it the early Christians who fell away or the modern Evangelicals? Why is Evangelicalism so different from the early Church?

Thus, the evidence shows that the Eucharist was at the center of early Christian worship – not the sermon. By subtly displacing the Eucharist and putting the sermon at the center of Christian worship, Calvin detached the heart and focus of worship from its Eucharistic moorings. Those who came after Calvin would go even further and strip Christian worship of its sacramental character. One only need witness today’s Protestant worship to see the absence of the Eucharist most every Sunday – much less the real presence of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist! This has resulted in the recent move among Protestants to restore liturgical worship, but even then the sermon still overshadows the Eucharist.

Altar, Vestments, and Ceremonies

Calvin taught that the early church celebrated the Eucharist with “great simplicity” (Institutes 4.10.19). But he is arguing from silence. He seems to be assuming that because the New Testament writings had little to say about how the early Christians worshiped that their worship was devoid of liturgical rites and ceremonies.

When we read the Old Testament we find biblical support for the use of altars, vestments, and ceremonies in worship. The Tabernacle had two altars: one for burnt offering (Exodus 27:1-8) and another for incense (Exodus 30:1-10). The priests were dressed in ornate vestments of gold, blue, purple, and scarlet in accordance with God’s directions to Moses (Exodus 28:1-5). Thus, Old Testament worship was an elaborate affair with processions, music, and ceremonies – nothing at all like the stark austere Reformed worship!

When we come to the New Testament we find no evidence of Old Testament worship being abolished and the instituting of minimalist worship with bare walls. We do, however, find hints of Old Testament worship being carried over into Christianity. In Hebrews 13:10 is a cryptic statement: “We have an altar . . . .” This was a reference to the Eucharistic celebration. The Christians saw themselves as the New Israel of Christ and in that light viewed the Eucharist as the continuation and fulfillment of the Old Testament sacrificial system. So we shouldn’t be surprised by Ignatius’ references to a Christian altar.

Be careful therefore to use one Eucharist (for there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup for union with his blood, one altar . . . . (Letter to the Philadelphians 4.1; emphasis added)

And,

Hasten all to come together as to one temple of God as to one altar, to one Jesus Christ, who came forth from the one Father, and is with one, and departed to one. (Letter to the Magnesians 7.2; emphasis added)

If the early Christians understood the Church as the Temple of the New Covenant then it is no surprise that they would view the clergy as the priests of the New Covenant (see Isaiah 66:19-21). All this makes sense in light of the fact that the Eucharist was central to early Christian worship. Thus, the wooden table or box (ark) where the priest celebrated the Eucharist would be considered an altar.

Icons

Calvin believed that the early churches were “completely free from visible representations” (Institutes 1.11.13). His assumption seems to be that because the New Testament had little to say about religious pictures in church buildings that icons were not part of early Christian worship.

But Calvin’s iconoclasm is weakened when we take into account the Old Testament passages about the images of the cherubim in the Tabernacle (Exodus 26:1, 31) and in the Temple (1 Kings 6:29-32).

Thus, the Old Testament places of worship were filled with visual representations: cherubim, palm trees, and flowers. Images of the cherubim were depicted on the curtain for the entrance to the Holy of Holies as well on the walls of the inner and outer rooms of the Temple. See my article: “The Biblical Basis for Icons.” In light of an absence of any New Testament passages mandating the removal of icons or the abolition of Old Testament worship we can assume some continuity between Jewish worship and early Christian worship.

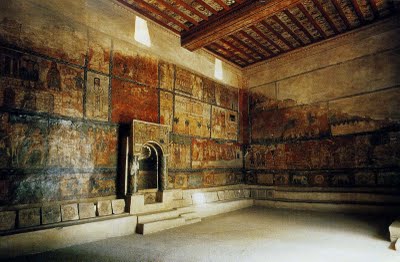

Recent archaeological research found that Jewish synagogues around the time of Christ were not bare rooms devoid of images but embellished with religious decorations. See my article “Early Jewish Attitudes toward Images.” Especially damaging to Calvin’s argument are the recent archaeological findings of images in the Jewish synagogue and Christian church in the town of Dura Europos which was buried circa 250. Taken together the biblical and archaeological evidences present a strong refutation of Calvin’s “Fall of the Church” theory.

Dura Europos Synagogue. Source

Defending the Gospel Message

A study of early church history shows that the church faced numerous theological challenges: Ebionitism which affirmed Jesus as Messiah but not as divine, Docetism and Gnosticism which denied that Jesus was truly human, Marcionism which saw the Old and New Testaments as representing two different religions and deities, and Montanism a prophetic movement which held that Apostolic tradition was superseded by the new prophecies. One thing that is striking is the absence of any controversy during this period over the issues mentioned by Calvin: liturgical worship, vestments, incense, or icons. Surely if the early Church had drifted away from the Apostles’ teachings as Calvin alleged someone would have spoken up?

The Apostle Paul was not unaware that the Church would come under attack by heretics so he took steps to ensure the safeguarding of the Gospel. At Timothy’s ordination to the office of bishop he admonished:

What you heard from me, keep as the pattern of sound teaching, with faith and love in Jesus Christ. Guard the good deposit that was entrusted to you—guard it with the help of the Holy Spirit who lives in us. (2 Timothy 1:13-14; NIV; emphasis added)

The phrases “pattern of sound words” and “good deposit” referred to a set of core doctrines to be held by all Christians. This was the basis for the theological unity of the early Church, to deviate from this doctrinal core was to fall into heresy. The early Christians were diligent in defending the orthodoxy of the Church. Ignatius warned Polycarp against tolerating those who taught “strange doctrine.” (Ignatius to Polycarp 3) A similar warning against “another doctrine” is found in Didache 11.1 and in Polycarp’s Letter to the Philippians (7.2).

In Against Heresies 1.22.1 Irenaeus referred to the “rule of faith (truth)” by which one could determine someone adhered to the Apostolic teachings or not. In Against Heresies 2.9.1 Irenaeus remarked how the entire Christian Church received the Apostles’ Tradition. Polycarp in Letter to the Philippians 7.2 made reference to the traditioning process as well.

The early church preserved the Apostles’ teachings by means of the bishop having received a body of teaching from his predecessor, the bishop as the primary teacher of the local church, and the congregation united with the bishop at the weekly Eucharistic celebration. For Irenaeus theological orthodoxy was linked to the bishop’s role in the traditioning process.

True knowledge is [that which consists in] the doctrine of the apostles, and the ancient constitution of the Church throughout the whole world, and the distinctive manifestation of the body of Christ according to the successions of the bishops, by which they have handed down that Church which exists in every place, and has come even unto us, being guarded and preserved, without any forging of Scriptures, by a very complete system of doctrine, and neither receiving addition nor [suffering] curtailment [in the truths which she believes]; . . . . (Against Heresies 4.33.8; emphasis added; see also 3.3.1)

Irenaeus described his mentor Polycarp’s efforts to remember accurately the teaching and example of his mentor the Apostle John.

And as he [Polycarp] remembered their words, and what he heard from them concerning the Lord, and concerning his miracles and his teaching, having received them from eyewitnesses of the ‘Word of life,’ Polycarp related all things in harmony with the Scriptures. These things being told me by the mercy of God, I listened to them attentively, noting them down, not on paper, but in my heart. And continually through God’s grace, I recall them faithfully. (in Eusebius’ Church History 5.20.7, NPNF p. 371; emphasis added)

In other words, the early Christians did not play fast and loose with the Apostles’ teachings as one might infer from the “Fall of the Church” theory. Rather, they sought to preserve and transmit faithfully the Apostles’ teachings to later generations. If anyone dared to stray from the regula fidei they would have been excluded from the Eucharist. That is why the episcopacy and the Eucharist were so critical to the theological integrity of the early Church.

Priests and Bishops

Just as the Jewish temple had a priesthood so too did the early church have a priesthood (clergy). Under the New Covenant the Eucharist was based on Christ’s once and for all sacrifice on the Cross. The bishop along with the priests (presbyters) presided over the Eucharistic assembly. Ignatius was an early witness to the three orders: bishops, priests, and deacons.

Be zealous to do all things in harmony with God, with the bishop presiding in the place of God and the presbyters in the place of the Council of the Apostles, and the deacons, who are most dear to me, entrusted with the service of Jesus Christ . . . . (Letter to the Magnesians 6.1; emphasis added)

He viewed this threefold hierarchy, not as optional, but as necessary.

Likewise let all respect the deacons as Jesus Christ, even as the bishop is also a type of the Father, and the presbyters as the council of God and the college of Apostles. Without these the name of “Church” is not given. (Letter to the Trallians 3.1; emphasis added)

In his Letter to the Smyrneans 8 Ignatius stressed that the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper were not valid unless done with the consent of the bishop. Irenaeus made a similar point as well:

Wherefore it is incumbent to obey the presbyters who are in the Church, — those who, as I have shown, possess the succession from the apostles; those who, together with the succession of the episcopate, have received the certain gift of truth, according to the good pleasure of the Father. (Against Heresies 4.26.2,)

An examination of church history shows that the episcopacy was the universal form of church governance. It was not until the Protestant Reformation that we see the emergence of novel polities: congregationalism, presbyterianism, and independent non-denominationalism.

Assessing Calvin’s “Fall of the Church” Theory

While insightful, Ralph Winter’s essay seems to have overlooked some of the startling theological implications of the BOBO theory. One implication is that the Holy Spirit was active in the early days of the church then disappeared for the next thousand years or more then reappeared with the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s! Also, Winter did not discuss Christ’s promise in John 14:26: “but the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you all things and will remind you of everything I have said to you.” This has profound implications for the doctrine of God’s sovereignty in history. For Reformed Christians this gap in church history also has troubling implications for God’s ability to keep his covenant promises. How can a Reformed Christian square his belief in the sovereignty of God and covenant theology with the “Fall of the Church” theory proposed by Calvin?

For me as a church history major the “Fall of the Church” theory stems from a foundational flaw. The “Fall of the Church” theory makes sense if one reads church history with the assumption that the early Christians were Calvinists. Any hints of liturgical worship among early Christians, i.e., anything unlike Reformed worship, can be attributed to their “falling away.” But this approach is like taking a meat cleaver and hacking church history into pieces! It utterly disregards the notion of historical continuity and development. A more reasonable approach is to view early Christian worship of the second century described in the post-apostolic writings as flowing from the Christian worship of the first century described in the New Testament. In light of the evidences one can then decide whether or not early Christian worship was liturgical, simple or elaborate, with or without icons. And whether or not there was continuity or significant departures in practice or doctrine. The second century writings are more useful for understanding first century Christian worship than those from the 1500s, the time of rhe Reformers.

Calvin’s BOBO theory of church history was influential in the Reformed tradition until Philip Schaff gave his “Principle of Protestantism” address in 1844. In it Schaff proposed that the Protestant Reformation represented the flowering of medieval Catholicism. Where Calvin saw discontinuity and rupture, Schaff saw continuity and evolution. Thanks to Schaff church history became an academic discipline that stood on its own independent of theology. This allowed for the emergence of historical theology. Jaroslav Pelikan’s The Christian Tradition is probably one of the finest works of historical theology in the twentieth century and extremely useful for understanding commonalities and divergences in the different theological traditions. [Note: This eminent Yale historian and long time Lutheran pastor to the surprise of many converted to Orthodoxy!]

Calvin’s theological system is complex and contains contradictions. These contradictions offer points of contact between the Reformed tradition and Eastern Orthodoxy. Despite his view that early Christianity had deteriorated over time, Calvin at times held some of the early church fathers in high regard. Calvin was not averse to quoting the church fathers against his Roman Catholic opponents. In his “Reply to Sadolet” Calvin affirmed the antiquity principle asserting “our agreement with antiquity is far closer than yours” (p. 231). Calvin’s arguments against the medieval church may be valid but does it likewise apply to the Orthodox Church? It has been noted that the Latin Church under the influence of medieval Scholasticism and the rise of the legal schools drifted away from its patristic roots. This suggests Calvin may have been a victim of historical circumstances. Calvin’s openness to the church fathers and the early Church laid the foundation of Mercersburg Theology in the 1800s and the attempt by Nevin and Schaff to bring back the catholic dimension to the Reformed tradition.

So while Calvin’s BOBO theory of church history is seriously flawed, he is to be commended for his willingness on occasion to draw on the early church fathers. This gives Reformed Christians an advantage over their Evangelical counterparts when it comes to engaging Eastern Orthodoxy. I found in Mercersburg Theology and the Reformed tradition a point of contact leading me to the early church and ultimately into the Orthodox Church. I am deeply indebted to Mercersburg Theology for the intellectual tools that enabled me to critically examine Reformed theology even though it had unintended consequences like my eventually converting to Orthodoxy.

Robert Arakaki

Source

Calvin, John. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Ford Lewis Battles, translator. The Library of Christian Classics. Volume XX. John T. McNeill, editor. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Calvin, John. 1964. “The Necessity of Reforming the Church” in Calvin: Theological Treatises, pp. 184-216. Editor: J.K.S. Reid. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Calvin, John. 1964. “Reply to Sadolet” in Calvin: Theological Treatises, pp. 221-256. Editor: J.K.S. Reid. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Eusebius. 1890. “The Church History of Eusebius” in Eusebius. Translator: Arthur Cushman McGiffert. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Second Series. Vol. I. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Ignatius. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers. Volume I. Loeb Classical Library. Editor: Kirsopp Lake. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Irenaeus. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers. Editors: Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Ante-Nicene Fathers. Volume I. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Justin Martyr. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers. Editors: Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Ante-Nicene Fathers. Volume I. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Polycarp. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers. Volume I. Loeb Classical Library. Editor: Kirsopp Lake. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Winter, Ralph D. 1992. “The Kingdom Strikes Back: Ten Epochs of Redemptive History.”

Recent Comments