Mercersburg Theology’s High Church Calvinism: A Dead End?

In recent years a renewed interest in Mercersburg Theology has emerged among Calvinists. This can be seen by Keith Mathison’s Given For You: Reclaiming Calvin’s Doctrine of the Lord’s Supper (2002), W. Bradford Littlejohn’s The Mercersburg Theology and the Quest for Reformed Catholicity (2009) and Jonathan G. Bonomo’s Incarnation and Sacrament: The Eucharistic Controversy between Charles Hodge and John Williamson Nevin (2010). See also Jonathan Bonomo’s blog Evangelical Catholicity.

In 1844, John Nevin and Philip Schaff teamed up at the German Reformed seminary in the tiny village of Mercersburg, Pennsylvania. From this collaboration came a stream of writings that challenged American Protestantism even up till this day. (#1, please see footnote section)

Stephen Graham wrote:

The story of Nevin and Schaff at Mercersburg is the story of an unlikely combination in the obscure seminary of a tiny immigrant denomination. …. They produced a theology that still stimulates and challenges thinkers concerned with theology and the Church (Graham 1995:91).

Mercersburg Theology can be understood as high church Calvinism. In their writings, Nevin and Schaff highlighted the fact that John Calvin’s theology was patristic, catholic, creedal, liturgical, and eucharistic.

Mercersburg Theology’s high church Calvinism may be a surprise to those who equate Calvinism with predestination. This close association with predestination reflects the influence of Dutch Calvinism on the English Puritans and Presbyterians in the 1600s. Nevin and Schaff, on the other hand, reflects the outlook of the German Reformed Church. On Mercersburg’s differences with Dutch Calvinism, Nevin wrote: “We will bear with their Calvinism on the decrees if they will bear with our Calvinism on the sacraments” (in Nichols 1966:19).

The significance of Mercersburg Theology lies in: (1) its attempt to forge a synthesis between Calvin and the early Church Fathers, (2) its affirmation of the real presence in the Lord’s Supper, and (3) its critique of the theological basis for Evangelicalism. In this posting I will assess Nevin and Schaff’s attempt to forge a catholic evangelical theology from the standpoint of the Reformers and the Church Fathers. It will also discuss how the foundational questions raised by Mercersburg Theology’s about Protestantism led to the author’s conversion to Orthodoxy. I have commented on Mercersburg Theology in earlier blog postings. In this posting I will be presenting an overall assessment and critique of this important theological movement.

A Catholic Evangelicalism

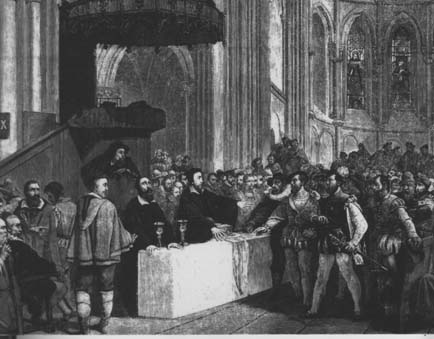

Mercersburg Theology introduced a startling new approach to church history. In his inaugural address upon assuming the professorship at the German Reformed Seminary, Philip Schaff shocked his audience by asserting that the Reformation was the flowering of the best in medieval Catholicism (Ahlstrom 1975:57).

The Reformation is the legitimate offspring, the greatest act of the Catholic Church…. (Schaff 1964:73)

Many in his audience were staunchly anti-Catholic viewing the Catholic Church as an ecclesiastical tyranny and the Pope as the Anti-Christ. He further scandalized them with the observation that Roman Catholicism had been a part of true Christianity up to the Reformation and was in some sense still a part of the true Church (Nichols 1961:170-171). Furthermore, Schaff looked forward to the eventual reunion of Protestantism and Roman Catholicism. What Schaff was attempting to do in his inaugural address was to present a Hegelian synthesis between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

Schaff’s dynamic historical understanding of the church, that shocked his audience was part of a general intellectual trend at the time in Europe. The German philosopher, Georg Hegel, played a major role in understanding world history as evolutionary and progressive. On the religious front, John Henry Newman used an evolutionary approach as the basis for his doctrine of development to enable him to accept the teachings of the Catholic Church. Although a small seminary in a minor denomination, Mercersburg was providentially positioned to introduce the most advanced German theological scholarship to American Protestantism which had become something of a provincial backwater.

Nevin and Schaff’s theological agenda was ambitious and wide ranging. They tackled Charles Finney’s revivalism, Charles Hodges’ symbolic understanding of the Lord’s Supper, John Henry Newman and the Oxford Movement, and Orestes Brownson’s Ultramontane Catholicism. Mercersburg Theology rests upon three premises: (1) the Incarnation, (2) Romanticism, and (3) the Hegelian dialectic. The starting point for their theology was the Incarnation. This was a momentous paradigm shift in which the emphasis was on the person of Christ rather than the work of Christ (Nichols 1966:78). Salvation would come to be viewed as union with Christ rather than forensic justification. Their theological perspective was also influenced by Romanticism — the view of the world as a living organic entity. Romanticism’s influence can be seen in their understanding of the church as the body of Christ, salvation as union with Christ, and the Lord’s Supper as a feeding on Christ’s body and blood. Mercersburg Theology rested upon the Hegelian dialectic. It was a dynamic and evolutionary approach to theology and church history that embraced diversity within Christianity. It saw dynamic synthesis as a source of blessing but static unresponsiveness as leading to missed opportunities (Ahlstrom 1975:56).

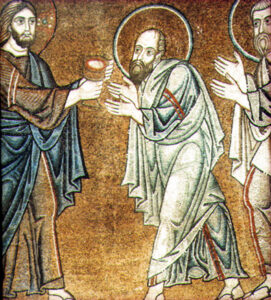

Recovering The Real Presence

One of Mercersburg Theology’s notable contribution to American Protestant theology has been the attempt to recover the doctrine of the real presence in the Lord’s Supper. By the early 1800s, much of American Protestantism had come to understand the Lord’s Supper as being a memorial — that is, only a symbol. Nevin and Schaff argued that Calvin and the Reformed churches held to the real presence in the Lord’s Supper.

Nevin wrote:

In the Lord’s Supper, accordingly, the believer communicates not only with the spirit of Christ, or with his divine nature, but with Christ himself in his whole living person; so that he may be said to be fed and nourished by his very flesh and blood (Nevin 1966:35).

To bolster his position, he excerpted part of Calvin’s Geneva Catechism:

Q. Do we then eat the body and blood of the Lord?

A. We do. For since the whole hope of our salvation consists in this, that his obedience, which he rendered to the Father, may be placed to our credit as though it were our own, it is necessary that he himself should be possessed by us. He does not communicate his benefits to us except as he makes himself ours. (in Nevin 1966:51)

From these quotes it is clear that Reformed theology historically affirmed the real presence in the Lord’s Supper.

Calvin’s understanding of the real presence can also be seen in the rubrics he prescribed for the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. An examination of the rubrics for the Strassburg Communion Service (1545) and the Genevan Communion Service (1542) reveals two things: (1) prayers affirming the real presence in the Communion Service, and (2) the absence of any prayer over the bread and wine. This omitting of the epiclesis — the prayer over the bread and the wine — marks a major break from the liturgical practice of the ancient Church

While Nevin affirmed the real presence, he rejected a localized real presence in the Eucharist (1966:310, 314, 316). He wrote:

…the Reformed Church taught that the participation of Christ’s flesh and blood in the Lord’s Supper is spiritual only, and in no sense corporal. The idea of a local presence in the case was utterly rejected. …. The manducation of it is not oral, but only by faith. (Nevin 1966:37-38; emphasis added)

In another place, Nevin stresses it is “only by the soul” we receive Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist (1966:274). Calvin likewise was averse to any understanding of a localized real presence in connection with the Eucharist; he saw such an understanding as resulting in Christ being “fastened,” “enclosed,” or “circumscribed” by the bread and wine (Institutes 4.17.19, 1960:1381). Probably the clearest example of Calvin’s rejection of a localized real presence can be found in the passage below:

Certainly Christ does not say to the bread that it shall become his body, but he commands his disciples to eat and promises them participation in his body and blood (Institutes 4.17.39; 1960:1416).

However, this is at odds with the first century Liturgy of St. James of Jerusalem (and other Orthodox anaphoras) which has a twofold epiclesis: upon the congregation and upon the Eucharistic elements.

Send down, O Lord, upon us and upon these gifts that lie before Thee Thy selfsame Spirit the all-holy that hovering with His holy and good and glorious coming He may hallow and make this bread the holy Body of Christ [The people: Amen.] and this cup the precious Blood of Christ [The people: Amen.] (in Dix 1945:191-192; italics in original; underscore added)

Thus, while Nevin’s understanding of the real presence was consistent with the Reformed tradition, it marked a break with the early Church.

Calvin understood the Lord Supper not so much in terms of the Holy Spirit’s descending from heaven transforming the bread and the wine, but the Christian believer being lifted up to heaven in mind and spirit by the symbols of bread and wine.

But if we are lifted up to heaven with our eyes and minds, to seek Christ there in the glory of his Kingdom, as the symbols invite us to him in his wholeness, so under the symbol of bread we shall be fed by his body, under the symbol of wine we shall separately drink his blood, to enjoy him at last in his wholeness (Institutes 4.17.18, 1960:1381; italics added).

Calvin was careful to make a distinction between the bread and wine as signs and the body and blood of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. It is as if he is describing two separate but parallel realities. Thus, despite the affirmation of the real presence, Calvin’s stance bears a striking resemblance to the memorialistic position. This is evident when he writes that “the Supper is nothing but a visible witnessing of that promise contained in the sixth chapter of John….” (Institutes 4.17.14, 1960:1376). In another place, Calvin described the Lord’s Supper as “a kind of exhortation” for us (Institutes 4.17.38; 1960:1414). The point here is not that the Calvin’s position is like the memorialistic one but that his understanding of the real presence is fundamentally at odds with that of the early Church.

Nevin and Schaff’s attempt to recover the real presence in the Eucharist was by and large a failure. They were unable to sway the opinions of the American Protestant theologians. From 1848 to 1850 Nevin engaged in a public debate with Charles Hodge over the doctrine of the real presence. (#3) Despite Nevin’s forceful rebuttal and Hodge’s failure to answer back, the memorialistic position became the dominant understanding in American Protestantism. Nevin’s inability to influence mainstream American Protestant theology, even with his formidable scholarship, points to the poignant fact that American Evangelicalism is impervious to genuine reform. Probably Nevin and Schaff’s biggest failure was their inability to bring about liturgical reform even within their own German Reformed Church. (#4) For all their attempts to recover the real presence, the doctrine remained just that, a doctrine. This means the de facto theology of American Protestantism was memorialistic despite Nevin and Schaff’s attempt to restore the historic Reformed doctrine of the real presence.

The Mystical Union and Our Salvation in Christ

The Incarnation forms the basis for Nevin’s understanding of salvation as mystical union with Christ (Nevin 1966:171). It links the believer organically to Christ’s suffering on the Cross and his third day resurrection (Nevin 1966b:80). It likewise forms the basis for our regeneration, sanctification, and resurrection (Nevin 1966:173-175). This enabled him to take an organic and developmental approach to salvation that went beyond the static, forensic understanding of justification widespread among Protestants. It also enabled him to counter the revivalism’s emotional approach to salvation.

The Incarnation forms the basis for Nevin’s understanding of salvation as mystical union with Christ (Nevin 1966:171). It links the believer organically to Christ’s suffering on the Cross and his third day resurrection (Nevin 1966b:80). It likewise forms the basis for our regeneration, sanctification, and resurrection (Nevin 1966:173-175). This enabled him to take an organic and developmental approach to salvation that went beyond the static, forensic understanding of justification widespread among Protestants. It also enabled him to counter the revivalism’s emotional approach to salvation.

Mercersburg’s incarnational theology linked our salvation in Christ to life in the church and to the Eucharist. He wrote:

In full correspondence with this conception of the Christian salvation, as a process by which the believer is mystically inserted more and more into the person of Christ, till he becomes thus at last fully transformed into his image, it was held that nothing less than such a real participation of his living person is involved always in the right use of the Lord’s Supper (Nevin 1966:31).

Nevin was fully aware that this is a consequential shift and took painstaking care to show this was a view shared by other Protestant thinkers, e.g., Richard Hooker, Martin Luther, and John Calvin (Nevin 1966b:86-87). He quotes Calvin:

In like manner, the flesh of Christ is like a rich and inexhaustible fountain that pours into us the life springing forth from the Godhead into itself. Now who does not see that communion of Christ’s flesh and blood is necessary for all who aspire to heavenly life? (Institutes 4.17.9; 1960:1369).

Calvin likewise understood the Lord’s Supper to be a key means by which we are united to Christ. He saw it as necessary for bringing about the resurrection of our bodies (Institutes 4.17.29; 1960:1399) and ensuring the immortality of our flesh (Institutes 4.17.32; 1960:1404). In his Genevan Catechism Calvin states: “…that we are joined to him with such union as holds between members and their proper head–in order that by the grace of this union we may become partakers of all his benefits.” (in Nevin 1966:51).

Nevin’s incarnational theology moved him in the direction of the early Church. His understanding of the Incarnation led to an appreciation of Christ as the Second Adam recapitulating human existence and restoring humanity to its original state, much like the second century Church Father, Irenaeus of Lyons (Nevin 1966b:83). Nevin’s teaching on the mystical union is strikingly similar to the Orthodox teaching of theosis. (#5)

The communion is spiritual, not material. It is a participation of the Savior’s life–of his life, however, as human, subsisting in a true bodily form. The living energy, the vivific virtue–as Calvin styles it–of Christ’s flesh, is made to flow over into the communicant, making him more and more one with Christ himself, and thus more and more an heir of the same immortality that is brought to light in his person (Nevin 1966:39).

But Nevin’s appreciation of the implications of the Incarnation is at best incomplete. His appreciation of the Incarnation fell short of the rich insights of the early Church Fathers. For example, he did not make use of Athanasius the Great’s widely quoted remark about our deification in Christ. In De Incarnatione Verbi Dei Athanasius wrote: “For he was made man that we might be made God” (§ 54.2; 1980:65). Irenaeus in Against the Heretics wrote: “…man making progress day by day, and ascending towards the perfect, that is, approximating to the uncreated One” (4.38.3; 1985:522). And it is surprising that Nevin did not make use of John of Damascus’ teachings on the divine energies in his exposition of the mystical union (3.15, 1983:60-64; 4.13, 1983:81-85; NPNF Vol. IX).

The Church the Body of Christ

Mercersburg Theology’s high church ecclesiology served as a corrective to low church Protestantism. The low church view was expressed in two ways: (1) the belief that while faith in Christ is essential for salvation, membership in the church is not, and (2) the view that denominational differences are acceptable and that one joined a church depending on individual preference. Nevin’s organic understanding of the Church led him to be critical of the understanding of the Church as a gathering of like minded individuals. It also led to the understanding that one cannot be a Christian apart from the Church (Nevin 1966b:66); to believe in Christ is to believe in the Church. He asserted forcefully:

The Church is his body, the fullness of him that filleth all in all. The union by which it is held together through all ages is strictly organic. The Church is not a mere aggregation or collection of different individuals, drawn together by similarity of interests and wants, and not an abstraction simply, by which the common in the midst of such multifarious distinction is separated and put together under a single general term. …. The Church does not rest upon its members, but the members rest upon the Church. (1966b:40; italics added).

His critique of denominational Christianity can be found in “Anti-Christ or the Spirit of Sect and Schism” (1848). Nevin saw in sectarian Christianity a view that downgraded the importance of the Church and sacraments, and which produced a disembodied Christianity. For Nevin who saw the Church as the extension of Christ’s Incarnation this attitude was tantamount to the heresy of gnosticism. Schaff’s organic view of the Church led him to similar views and to establish the discipline of Church history. (#6)

Mercersburg Theology’s high church Calvinism stemmed from its incarnational theology and from the influence of Romanticism. Taking the Incarnation as their starting point, Nevin and Schaff understood that the Church was a supernatural entity which owed its existence to Christ.

The Church is the historical continuation of the life of Jesus Christ in the world. By the Incarnation of the Son of God, a divine supernatural order of existence was introduced into the world, which was not in it as part of its own constitution before (Nevin 1966b:65).

This incarnational understanding of the Church implied a high church ecclesiology.

The idea of the Church, as thus standing between Christ and single Christians, implies of necessity visible organization, common worship, a regular public ministry and ritual, and to crown all, especially, grace-bearing sacraments (Nevin 1966b:90; emphasis in original).

The organic understanding of the Church as the body of Christ led Nevin to understand theology as a corporate effort. Theology is done within the Church, not independently of the Church. The Creed was not a summary of the Bible but an authoritative statement of the Christian Faith parallel to the Bible. Through the Creed one reads Scripture with the mind of the Church. To recite the Creed was to participate in the life of the Church. To abandon the Creed, i.e., not use it as a confessional statement or to neglect its use in worship, was a mark of a sect (Nichols 1961:177-178). In short, grounding ecclesiology in the Incarnation opens the door for the Church Fathers, the creeds, the ecumenical councils, and liturgies as theological resources as reflected in Mercersburg’s distinctive catholic evangelical theology.

The Unity of the Church

![]() Nevin and Schaff were opposed to the idea of the invisible church. Instead they posited an organic approach in which the ideal church existed as a dynamic principle within the actual church (see Nichols 1966:57 ff.). They saw church history as the working out of the reality of what the Church is and will be. This Hegelian approach to church history led them to believe that the Reformation originated as a reaction to the excesses of Roman Catholicism, and that the contradiction between Protestantism and Catholicism would one day be resolved in the ideal church (Nevin 1978:294).

Nevin and Schaff were opposed to the idea of the invisible church. Instead they posited an organic approach in which the ideal church existed as a dynamic principle within the actual church (see Nichols 1966:57 ff.). They saw church history as the working out of the reality of what the Church is and will be. This Hegelian approach to church history led them to believe that the Reformation originated as a reaction to the excesses of Roman Catholicism, and that the contradiction between Protestantism and Catholicism would one day be resolved in the ideal church (Nevin 1978:294).

The Church as it now stands is the result of what the same Church has been since the time of Christ; the past is gathered up and comprehended in the present; and the whole is reaching forward to still new developments in the future, that will cease only when the Ideal Church and the actual Church shall have become fully and forever one (Nevin 1966b:62).

Nevin saw church history as a conservative evolution, constantly taking on new forms but remaining unchanged in its essence (Nevin 1966b:312).

The Hegelian dialectic enabled Nevin and Schaff to generously include small sects along with Roman Catholicism in the one Church. While critical of the “sect system,” Nevin saw them as an early stage of the Reformation that would one day in the future be resolved through Protestantism evolving into a more advanced form of Christianity (1966b:46). Schaff saw sects in more charitable terms: “a disciplinary scourge” and “voice of awakening and admonition” (1964:171-172). Sects served as a corrective to the Church and they will lose their right to exist once the original church body has made the necessary adjustments.

One flaw of Mercersburg’s ecumenicism was that its Hegelian dialect was framed by Western Christianity: between the English Oxford Movement and American frontier revivalism, and between Protestantism with Roman Catholicism. They failed to grapple the more fundamental divisions in Christendom such as the Great Schism of 1054. Where Western Christianity had an evolutionary understanding of theology as science, Orthodoxy’s staunch adherence to Tradition and its rejection of theological innovation renders the Hegelian method extremely problematic. Mercersburg’s failure to engage the claims of Eastern Orthodoxy is all the more puzzling in light of their familiarity with patristic theology.

One of the strongest arguments against Nevin and Schaff’s Hegelian approach to church unity is that historical developments since then has not progressed towards resolution of denominational differences but rather to further divisions and doctrinal innovations. Ironically, one good example of this is Mercersburg Theology itself. Mercersburg Theology became a major obstacle preventing union between the German Reformed and Dutch Reformed churches (Nichols 1966:35). The United Church of Christ, the successor denomination to the German Reformed Church, the church body Nevin and Schaff belonged to, is widely known for theological liberalism which dispensed with many historic beliefs and practices. (#7) In the broader sense, Mercersburg’s ecumenical paradigm has been refuted by Protestantism’s general trend towards greater fragmentation and theological innovation. Protestantism in the twentieth century has seen the rise of Pentecostalism, liberalism, and fundamentalism. Protestantism has mutated — undergone fundamental changes in form (worship) and content (doctrine) — such that one could question whether they can be considered Protestant, i.e., sharing the same doctrine and worship as Luther and Calvin. It would be extreme and absurd to maintain that the recent innovations will one day lead to Church unity.

One of the more problematic aspects of Mercersburg’s ecclesiology was the attempt to portray Protestantism as a continuation of the early Church and not some schismatic breakaway sect. Nevin asserted that the Reformation was not a repudiation of the early Church, but rather it built upon the early Church. He asserts that if the Reformation was a revolution, it would be a new religion (Nevin 1978:292). Nevin considered historical continuity as the basis for Protestantism’s validity. Nevin writes:

…Protestantism, if it have any right to exist at all, is the true historical continuation of the ancient church (1978:281).

Nevin made it a point to insist that Protestantism being rooted in the Reformation is marked by adherence to the Creed and to the sacraments. However, applying Nevin’s criteria meant that much of modern Evangelicalism and mainline denominations today cannot be considered Protestant, and if they cannot be considered Protestant on what basis can they be considered to be part of the historic Christian Faith?

Protestantism’s claim to be in historic continuity with the early Church proved to be especially problematic for Nevin. At one point Nevin underwent a personal crisis — known as “Nevin’s dizziness” — during which he wrestled with whether he could remain Protestant. (#8) Nevin’s dizziness was not an isolated event; similar crises were happening elsewhere. In England, John Henry Newman, a leader of the Oxford Movement in the Church of England, converted to Roman Catholicism in 1845. Closer to home, Orestes Brownson, an American Universalist minister, had converted to Catholicism in 1843. Nevin remained a Protestant although his personal crisis strained his friendship with Schaff (Graham 1995:79). A related theological crisis is taking place today: Questions about Protestantism’s validity has caused numerous recent conversions to Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. (#9)

Mercersburg Versus Subjectivism

While Nevin and Schaff’s catholic evangelicalism has caught the attention of scholars, their dispute with “Puritanism” is just as significant. “Puritanism” was a low church movement that emphasized salvation as an emotional experience, the sacrament as purely symbolic, and the individual interpretation of the Bible. “Puritanism” (#10) was part of a broad movement — the subjective turn — that altered American religious life radically. (#11) As Americans crossed the Appalachians they left behind the constraints and institutions of urban life. In this new environment novel forms of belief and religious life emerged; an understanding emerged that saw the spiritual as inward and subjective — “heart felt.”

The subjective turn was a consequential religious paradigm shift. It led to the view that faith in Christ must be a conscious personal experience. It caused people to question the adequacy of faithful church attendance and the catechetical process without a salvation experience. Similarly, it led to the rejection of infant baptism in favor of adult baptism. This subjective emphasis spread through the revivalist movement popularized by Charles Finney. Revivalism was the view that to be saved one needed an emotional experience of salvation. To facilitate this the “anxious bench” was created in which people with a troubled conscience would go up, sit down, and request prayer for their salvation. This would later evolve into the modern altar call popularized by Billy Graham. This outlook swept through the Presbyterian churches in eastern Pennsylvania and the Ohio valley. Nevin wrote The Anxious Bench (1843) in which he criticized the importance placed on emotionalism and defended churchly Christianity in the form of creeds and catechetical instruction, and the efficacy of the sacraments, e.g., infant baptism.

The subjective turn impacted church life as well. Men were ordained on the basis of their oratorical skills or their charismatic personalities without any approval by church authorities. Preachers were free to promulgate new doctrines unchecked by creeds or church authorities, and people were free to join whatever church body they found to their liking. New interpretations of the Bible surfaced resulting in a profusion of denominations, and ironically even to anti-denominational groups as well. Out of this confusion emerged the slogan: “No creed but the Bible.” The subjective turn transformed America’s religious landscape. In addition to giving rise to new forms of Protestantism, it gave rise to new religious groups that went beyond the boundaries of Christianity: the Jehovah Witnesses, the Seventh Day Adventists, and the Latter Day Saints (Mormons). Nevin and Schaff’s attempts to counter the influence of “Puritanism” in the Reformed churches must be viewed against this broader social context.

Mercersburg’s dispute with “Puritanism” is important because modern Evangelicalism’s roots can be traced to “Puritanism” in the 1800s. This influence can be seen in modern Evangelicals’ fast and loose approach to doctrine, church order, the sacraments, and liturgical worship. Among Evangelicals salvation is understood in terms of “making a decision for Christ” or responding to the altar call, instead of baptismal regeneration. Doctrine is based upon one’s subjective understanding of the Bible or upon a personal revelation of the Holy Spirit apart from the historic creeds. Worship is understood to be the outward expression of one’s inward feelings for God. Lacking fixed forms or rituals, Evangelical worship has evolved in many directions: traditional with hymns, seeker friendly, mega church with rock bands and power point presentations, intimate emergent churches, and the eclectic ancient-future worship.

Mercersburg Theology sought to provide a corrective to Puritanism’s subjective turn by emphasizing the Church as the body of Christ and the Spirit of God working in the Church through the sacraments and the Creed. Mercersburg’s critique of “Puritanism” raises a number of fundamental questions about the theological basis for modern Evangelicalism. Evangelicalism’s non-response to the Mercersburg critique even till now raises questions about its capacity to engage in serious theological inquiry and its capacity for genuine reform.

A Link Between Calvinism and Orthodoxy?

Mercersburg Theology offers the promise of an ecumenical bridge between Calvinism and Eastern Orthodoxy (see Littlejohn chapter 5). However, despite Nevin and Schaff’s reliance on the Church Fathers there are a number of significant differences between Mercersburg and Orthodoxy: (1) the Nicene Creed, (2) the Filioque clause, (3) the Ecumenical Councils, (4) Mary as the Theotokos (God-Bearer), and (5) the use of icons in worship. An Orthodox Christian would find it puzzling that Nevin and Schaff made use of the Apostles Creed but not the Nicene Creed. Another point of difference is their acceptance of the Filioque clause by default (see Nevin 1966:173). Schaff observed that it was not considered a topic for debate among the Reformers and that Protestants were free to go either way (1910:477). Nevin and Schaff’s failure to deal with Orthodoxy’s objections to the Filioque showed their failure to take seriously the Orthodox understanding of theology as Tradition. Another fundamental point of difference is their understanding of the Councils as fallible human events (Schaff 1964:105). Orthodoxy on the other hand insists that the Holy Spirit infallibly guided the Councils in their decisions and that the decisions of the Councils are binding on all Christians (see Ware 1963:248, 251-254).

One major obstacle is Mercersburg’s evolutionary approach to theology. Nevin and Schaff understood theology as “a continuously progressive science.” This attitude also influenced their attitude towards the early Church. Schaff in his conversation with Edward Pusey challenged Pusey’s adherence to the Church Fathers with: “Why should we remain in the child period?” (in Pretila 2009). This attitude contradicts Orthodoxy’s belief in an absolute and unchanging Tradition (Ware 1963:197; pace Nevin 1966b:312). The common complaint that Orthodoxy theology is static confirms the Orthodox understanding of theology as Tradition and raises the question whether Mercersburg’s dialectical approach can be applied to Orthodox theology.

The doctrine of the Incarnation which provides Mercersburg a point of contact with Orthodox theology is also a source of numerous differences. Nevin and Schaff fell short in understanding the full implications of the Incarnation. They did not grapple with the early Church’s affirmation of the Virgin Mary as the New Eve who reversed the Fall and the early Church honoring her as the Theotokos in the context of Christian worship. Furthermore, they did not grasp the full implications of the Incarnation for worship. This can be seen in their relative silence on the role of icons in Christian worship. Schaff understood icons primarily in terms of the relation of art and worship (1910:448-449). The early Church Fathers grounded their theology of icons in the Incarnation and saw iconoclasm with its implicit Nestorianism to be an attack on the doctrine of the Incarnation.

Accessing the Church Fathers

A profound and beneficial legacy of Mercersburg Theology is the massive 28 volume Nicene and Post-Nicene Church Fathers series edited by Schaff (#12). Thanks to Schaff, Evangelicals today can read for themselves the writings of the first century Apostolic Fathers, such as: Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great, Augustine of Hippo, John Chrysostom, John of Damascus and many others. But when modern Evangelicals read the Church Fathers first hand, they find themselves in a strange land where the inhabitants speak a barely comprehensible language. Nevin wrote in “Early Christianity”:

To read Ignatius, or Polycarp, or Justin Martyr, or Irenaeus, or Tertullian, is to feel ourselves surrounded in the very act with a churchly element, a sense of the mystical and supernatural, which falls in easily enough with the later faith of the primitive church, but not at all with the keen clean air of modern Puritanism, as this sweeps either the heaths of Scotland or the bleak hills of New England (1978:233).

The frustration of Mercersburg Theology is that it cannot bring us to the promised land. The most we can do is wait for the historical dialectic to work itself out and be resolved in the future ideal church. This is where Eastern Orthodoxy presents a strong challenge to Mercersburg Theology. What for a Protestant is terra incognita is familiar territory for today’s Eastern Orthodox Christians. After several years of attending a Greek Orthodox parish I had a shock of recognition when I read St. Cyril of Jerusalem’s Catechetical Lectures (NPNF Vol. VII) which matched what I had witnessed in the Holy Week services. Where Mercersburg offered indirect access to the early Church, direct access can be found through the liturgical life of the Orthodox Church.

While Nevin and Schaff made ample use of the early Church Fathers, the gap between the Church Fathers and later Protestants raises serious questions and concerns. First, do Protestants have the same theology as the early Church or is Protestantism an entirely different theological system? Second, can one fully access the Church Fathers by simply reading them? Third, can one claim to be a part of the same Church by simply reading and citing their writings? (#13)

Fundamentally, Mercersburg Theology like much of Protestantism is grounded in the autonomous self-taught individual. Just as Luther initiated the Reformation by breaking with Roman Catholicism, so Nevin and Schaff sought to reform their eighteenth century German Reformed denomination by breaking with the prevailing “Puritanism” in American Protestant Christianity. This was not the case with the early Church. In the early Church the teaching authority resided with the bishops, the successors to the Apostles (see Ware 2000:17; Ignatius “To the Philadelphians” IV). The emphasis in the early church was on continuity in Tradition, not reform and change. Without the Church as an Eucharistic community assembled under the bishops, Mercersburg Theology being rooted in the academy inevitably ends up with a semi-gnostic ecclesiology. It is gnostic because its approach is basically academic, not organic. Despite their high churchmanship and their attempt to introduce liturgical reform to the German Reformed Church, Nevin and Schaff failed to make the Eucharist central to the life of the church. In the early Church it was impossible to do theology apart from the Eucharist. Irenaeus of Lyons, a second century Church Father, wrote:

Fundamentally, Mercersburg Theology like much of Protestantism is grounded in the autonomous self-taught individual. Just as Luther initiated the Reformation by breaking with Roman Catholicism, so Nevin and Schaff sought to reform their eighteenth century German Reformed denomination by breaking with the prevailing “Puritanism” in American Protestant Christianity. This was not the case with the early Church. In the early Church the teaching authority resided with the bishops, the successors to the Apostles (see Ware 2000:17; Ignatius “To the Philadelphians” IV). The emphasis in the early church was on continuity in Tradition, not reform and change. Without the Church as an Eucharistic community assembled under the bishops, Mercersburg Theology being rooted in the academy inevitably ends up with a semi-gnostic ecclesiology. It is gnostic because its approach is basically academic, not organic. Despite their high churchmanship and their attempt to introduce liturgical reform to the German Reformed Church, Nevin and Schaff failed to make the Eucharist central to the life of the church. In the early Church it was impossible to do theology apart from the Eucharist. Irenaeus of Lyons, a second century Church Father, wrote:

But our opinion is in accordance with the Eucharist, and the Eucharist in turn establishes our opinion (Adversus Haereses 4.18.5; 1985:486).

This is reflected in the ancient theological principal: lex orans, lex credendi (the rule of prayer is the rule of faith). The theology of the early Christians was embedded in the liturgy. The liturgy served both an expressive and a regulative function in relation to the theology of the early Church. Today Mercersburg theology is more of an academic movement than a liturgical tradition rooted in the local church. There have been attempts among some of the smaller Reformed denominations to hold weekly Eucharist and adopt a form of high church Calvinism. It remains to be seen if this will develop into a major reform movement or fade away into another fad that came and went.

While Nevin and Schaff affirmed the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist they failed to grasp the deeper ecclesiological significance of the real presence. The Church is fundamentally an Eucharistic community. Henri De Lubac, a Catholic theologian, put it aptly: The Church makes the Eucharist and the Eucharist makes the Church. It is in the Eucharist where we truly receive the Body and Blood of Christ and where the basis for Christian unity is found. The Eucharist is the integrating center of the Church. Eucharistic communion is what unites Christians across time and space. The Eucharist as a received tradition links the local church to the Apostles. The fact that the Reformation was grounded in the rupture of communion with the Church of Rome leaves the status of Protestant Christianity in a very tenuous state.

Mercersburg Theology as a Dead End

Mercersburg Theology as a Dead End

In terms of theology and worship Protestantism has undergone considerable evolution to the point that it can be regarded as a different religion altogether. Where Eastern Orthodoxy retains a direct link to the early Church, Protestantism has no similar connection. Mercersburg Theology attempted to restore this historic continuity through liturgical reform, reinstating the catechumenate, and a renewed appreciation for the early Church and the Church Fathers. For all their efforts, Nevin and Schaff’s attempt to bring the German Reformed Church back to its historic roots fell by the wayside; Mercersburg Theology became a theological obscurity known only to theologically sophisticated Protestants or academics. A more disturbing conclusion for me was the realization that the early Church Fathers would deny Communion to Protestants, including Luther, Calvin, not to mention Nevin and Schaff and modern day Calvinists. This can be seen in the Orthodox Church’s refusal to enter into ecumenical dialogue with the Lutherans in the 1500s and the formal repudiation of Calvinism in “The Confession of Dositheus” (1672) (in Leith 1982:485-517).

Mercersburg Theology represents a valiant attempt to reconnect with the Church’s ancient roots and to recover the unity of the Church but it is in reality a dead end. It can’t get us there. It is like a path in the mountain that takes one to a breath taking look out point overlooking a cliff with no way down there. Thanks to Nevin and Schaff I became aware of the early Church Fathers but I found myself outside their Church. The questions and issues raised by Nevin and Schaff led me to the conclusion that the Church Fathers would consider the Evangelical circles I belonged to as heterodox at best and heretical at worst. This led me to the conclusion that for all its good intentions, the high goals of the Mercersburg Project cannot be achieved until its Protestant premises are jettisoned and the historic Faith of Orthodoxy accepted. I owe much to the Mercersburg theologians, John Nevin and Philip Schaff. I view my conversion to Orthodoxy not as a repudiation of Mercersburg Theology but its fulfillment.

Robert Arakaki

Note: I would like to thank Jonathan Bonomo for his comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We may not always be in agreement, but I appreciate his love for the church and his concern for rigorous scholarship.

Footnotes

#1 — For an overview of Mercersburg Theology see Nevin’s letter to Henry Harbaugh (1978:405-411), Nichols’ introductory chapter to Mercersburg Theology (1966), and Chapter 38 in Vol. 2 of Ahlstrom’s A Religious History of the American People (1975). For a comprehensive bibliography of Nevin’s writings see Hamstra and Griffoen 1995:233-244. For a bibliographic overview of Schaff’s writings see Penzel 1991:367-368 and Pranger 1997:293-298.

#2 — These two quotes represent a minute portion of Nevin and Calvin’s writings on the Lord’s Supper. For a more comprehensive overview see Nevin’s The Mystical Presence. Calvin’s understanding of the Lord’s Supper can be found in his Institutes 4.17 and in Calvin: Theological Treatises (J.K.S. Reid, ed.).

#3 — See Bonomo’s Incarnation and Sacrament (2010) and Nichols’ Romanticism in American Theology, chapter 4.

#4 — Nevin and Schaff were part of a committee that produced a provisional liturgy but that liturgy failed to make any substantial impact on the denomination. Nevin was not surprised by the ineffectual impact of the provisional liturgy and was resigned to it (see his “Vindication of the Revised Liturgy” 1978:313 ff.). Schaff professed “indifference” whether or not the Provisional Liturgy was accepted (in Yrigoyen and Bricker 1979:424).

#5 — See chapter 5 of Littlejohn’s The Mercersburg Theology and the Quest for Reformed Catholicity (2009) for an attempt to use the doctrine of theosis as a point of commonality between Mercersburg and Eastern Orthodoxy.

#6 — See Schaff’s long essay “What Is Church History?” (in Yrigoyen and Bricker 1979:17 ff.) in which he shows the importance of church history for theology.

#7 — Ironically, Schaff in his post-Mercersburg period helped pave the way with his support for the revision of the Westminster Confession of Faith. See his essay “Creed Revision in the Presbyterian Churches” in Penzel 1991:280-292.

#8 — The exact nature or cause of Nevin’s personal crisis is not known. What is known is that from 1850 to 1855 Nevin resigned his various responsibilities and essentially became a recluse. During that time he wrote 8 articles for the Mercersburg Review totaling some 300 pages. These articles showed a pronounced sympathy for the Roman Catholic position. See Noël Pretila’s “Oxford Movement’s Influence upon German American Protestantism: Newman and Nevin” for a detailed discussion of Nevin’s dizziness. See also Pranger 1987:115-119 and Wentz 1987:26-27.

#9 — Examples include Scott Hahn, Thomas Howard, and Francis Beckwith, a former president of the Evangelical Theological Society, who converted to Roman Catholicism. On the Eastern Orthodox side there are Peter Gillquist, Frank Schaeffer, Michael Harper, and Jaroslav Pelikan. In my case, Mercersburg Theologically precipitated the collapse of my Protestant theology and forced me to give serious consideration to Eastern Orthodoxy.

#10 — The “Puritanism” that Nevin and Schaff railed against referred to low church Protestants in ante-bellum America in the 1800s, not the Puritans in the 1600s (Griffoen 1995:127).

#11 — The term “subjective turn” is the author’s. It is different from Heelas and Woodhead’s which they used to describe the shift from religion to spirituality.

#12 — Although Schaff edited and published the series while he was professor at Union Seminary in New York long after he had left Mercersburg, the Church Fathers series, nonetheless, represent the culmination of what he and Nevin had hoped to accomplish decades earlier.

#13 — In an email Jonathan Bonomo criticized the notion of “the Fathers as a generalized entity utilized in service to polemics” and which give little “attention to historical or literary context.” Here Bonomo is very much a disciple of Nevin and Schaff who did theology and church history by drawing on the critical scholarship of Europe’s leading university. While critical historiography is a very important academic discipline, it should be kept in mind that theology in the Orthodox Church is done through a historical consensus and ecclesial process quite different from the scholastic criteria of the academy.

REFERENCES

Ahlstrom, Sidney E. 1975. A Religious History of the American People. Volume 2. Garden City, New York: Image Books.

Armstrong, Chris. 2008. “The Future Lies in the Past” Christianity Today. Posted 8 February 2008. http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/article_print.html?id=53546

Athanasius. 1980. “De Incarnatione Verbi Dei.” St. Athanasius: Select Works and Letters. Volume IV of The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, eds. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Basil the Great. n.d. The Divine Liturgy of Our Father among The Saints Basil The Great (according to the use of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America). Stanton, New Jersey: Saint Luke’s Priory Press.

Bonomo, Jonathan G. 2010. Incarnation and Sacrament: The Eucharistic Controversy between Charles Hodge and John Williamson Nevin. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock.

Calvin, John. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion. The Library of Christian Classics Vol. XX. John T. McNeill, ed. Translated by Ford Lewis Battle. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Calvin, John. 1977. Calvin: Theological Treatises. Translated with Introduction and Notes by J.K.S. Reid. The Library of Christian Classics – Ichthus Edition. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Cyril of Jerusalem. 1983. “The Catechetical Lectures.” Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Volume VII. Series Two. Edwin Hamilton Gifford, translator. Reprinted 1983. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

DiPuccio, William. 1998. The Interior Sense of Scripture: The Sacred Hermeneutics of John W. Nevin. Studies in American Biblical Hermeneutics 14. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press.

Dix, Gregory. 1945. The Shape of the Liturgy. Second printing 1985. New York: Seabury Press.

Gillquist, Peter E. 1979. The Physical Side of Being Spiritual. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House.

Graham, Stephen. 1995. “Nevin and Schaff at Mercersburg.” In Reformed Confessionalism in Nineteenth-Century America: Essays on the Thought of John Williamson Nevin, pp. 69-96. Sam Hamstra, Jr. and Arie J. Griffoen, edited. Lanham, Maryland: The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Griffoen, Arie J. 1995. “Nevin on the Lord’s Supper.” In Reformed Confessionalism in Nineteenth-Century America: Essays on the Thought of John Williamson Nevin, pp. 113-124. Sam Hamstra, Jr. and Arie J. Griffoen, editors. Lanham, Maryland: The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Hamstra, Jr., Sam and Arie J. Griffoen, editors. Lanham, Maryland: The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Heelas, Paul and Linda Woodhead. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Hodge, Charles. 1848. “On the Lord’s Supper.” Princeton Review, 227-278. (April)

Ignatius of Antioch. 1912. “To The Philadelphians.” In The Apostolic Fathers, Vol I, pp. 239- 249. The Loeb Classical Library. Kirsopp Lake, translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Irenaeus of Lyons. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers With Justin Martyr and Irenaeus. Volume I of The Ante-Nicene Fathers. Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Press.

John of Damascus. 1983. Exposition of the Orthodox Faith. The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Second Series. Volume IX. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, editors. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Press.

Leith, John H., ed. 1982. Creeds of the Churches: A Reader in Christian Doctrine From the Bible to the Present. Third Edition. First published 1963. Atlanta, Georgia: John Knox Press.

Littlejohn, W. Bradford. 2009. The Mercersburg Theology and the Quest for Reformed Catholicity. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock.

Mathison, Keith A. 2002. Given For You: Reclaiming Calvin’s Doctrine of the Lord’s Supper. Phillipsburg, New Jersey: P&R Publishing.

Nevin, John W. 1978. Catholic and Reformed: Selected Theological Writings of John Williamson Nevin. Charles Yrigoyen, Jr. and George H. Bricker, eds. Pittsburgh Original Texts and Translations Series Number 3. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Pickwick Press.

Nevin, John W. 1966. The Mystical Presence and other writings on the Eucharist. Volume 4 in the Lancaster Series on the Mercersburg Theology, Bard Thompson and George H. Bricker, eds. Philadelphia and Boston: United Church Press.

Nevin, John W. 1966b. The Mercersburg Theology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nevin, John W. 1964. “Introduction.” In The Principle of Protestantism, pp. 27-52. Originally published 1845. Volume One in the Lancaster Series on the Mercersburg Theology, Bard Thompson and George H. Bricker, eds. Philadelphia and Boston: United Church Press.

Nevin, John W. 1855. “The Christian Ministry.” The Mercersburg Quarterly Review, 68-93. Originally published by the Alumni Association of Marshall College. Digitized form: http://books.google.com/books?id=xWc2AAAAMAAJ Site visited October 8, 2010.

Nichols, James Hastings, ed. 1966. The Mercersburg Theology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nichols, James Hastings. 1961. Romanticism in American Theology: Nevin and Schaff in Mercersburg. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Noll, Mark A. 1984. “Mercersburg Theology.” In Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, pp. 707-708. Walter A. Elwell, ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Penzel, Klaus, ed. 1991. Philip Schaff: Historian and Ambassador of the Universal Church, Selected Writings. Edited and with Introduction by Klaus Penzel. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press.

Pranger, Gary K. 1987. Philip Schaff (1819-1893): Portrait of an Immigrant Theologian. Vol. 11 of the Swiss American Historical Society Publications. Leo Schelbert, General Editor. New York: Peter Lang.

Pretila, Noël. 2009. “The Oxford Movement’s Influence upon German American Protestantism: Newman and Schaff” in Credo ut Intelligiam. Site visited October 8, 2010. http://theologyjournal.wordpress.com/2009/01/17/the-oxford-movement’s-influence-upon-german-american-protestantism-newman-and-nevin/ Posted January 17, 2009.

Schaff, Philip. 1910. Modern Christianity: The Swiss Reformation. Volume VIII of History of the Christian Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Schaff, Philip. 1910. Medieval Christianity: From Gregory I to Gregory VII A.D. 590-1073. Volume IV of History of the Christian Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Schaff, Philip. 1964. The Principle of Protestantism. Volume I of Lancaster Series on the Mercersburg Theology. Bard Thompson and George H. Bricker, editors. Philadelphia and Boston, United Church Press.

Thompson, Bard. 1961. Liturgies of the Western Church. Selected and Introduced by Bard Thompson. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Thompson, Bard, Hendrikus Berkhof, Eduard Schweizer, and Howard G. Hageman. 1963. Essays on the Heidelberg Catechism. Philadelphia and Boston: United Church Press.

Ware, Kallistos (Timothy). 2000. The Inner Kingdom. Volume I of the Collected Works. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Ware, Timothy. 1963. The Orthodox Church. Reprinted 1973. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books.

Wentz, Richard E. 1987. John Williamson Nevin: American Theologian. New York: Oxford University Press.

Yrigoyen Jr., Charles and George M. Bricker, editors. 1979. Reformed and Catholic: Selected Historical and Theological Writings of Philip Schaff. Pittsburgh Original Texts and Translations Series. Dikran Y. Hadidian, general editor. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Pickwick Press.

Recent Comments