Part 2 of 4.

One striking feature about the recent promotions of the Geneva Bible is the reworking of church history. They depict a tyrannical King James who oppressed freedom loving Puritans and how the Geneva Bible played a pivotal role in the emergence of democracy in America, but history is more complicated than that.

The website for Studylight.org claims:

The notes also infuriated King James, since they allowed disobedience to tyrannical kings. King James went so far as to make ownership of the Geneva Bible a felony. He then proceeded to make his own version of the Bible, but without the marginal notes that had so disturbed him. Consequently, during King James’s reign, and into the reign of Charles I, the Geneva Bible was gradually replaced by the King James Bible. (Emphasis added; Source)

In a similar vein we find Kirk Cameron claiming:

The English church had become little more than an arm of the State, and the English Reformation was losing steam. Just then The Geneva Bible was providentially unleashed on a dark, discouraged, downtrodden people, and it was the spark for a Christian Reformation of life and culture the likes of which the world had never seen. (Emphasis added; Source)

It would not be accurate to describe the Puritans as a freedom loving people. There is a theocratic streak in the Puritan Project. For example, in Scotland a law was passed mandating that everyone over a certain income purchase a copy of the Geneva Bible! It seems to this writer that what the neo-Reformed are attempting to do is reimagine the past to advance their theological agenda.

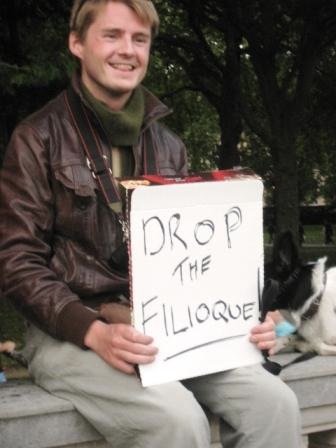

Stoolball equipment from modern day reenactment event.

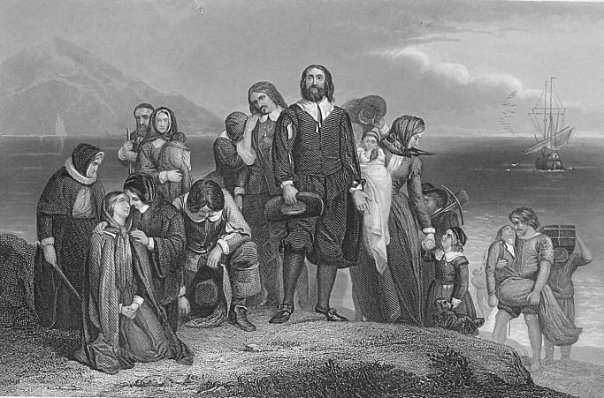

Because of their strict biblicism the Pilgrims had a restrictive understanding of culture. This can be seen in their views on Christmas which they saw as a Romish invention lacking biblical support and therefore contrary to the Christian way of life.

Nathaniel Philbrick in Mayflower (2006) described the first Christmas in the New World:

For the Pilgrims, Christmas was a day just like any other; for most of the Strangers from the Fortune, on the other hand, it was a religious holiday, and they informed Bradford that it was “against their consciences” to work on Christmas. Bradford begrudgingly gave them the day off and led the rest of the men out for the usual day’s work. But when they returned at noon, they found the once placid streets of Plymouth in a state of joyous bedlam. The Strangers were playing games, including stool ball, a cricketlike game popular in the west of England. This was typical of how most Englishmen spent Christmas, but this was not the way the members of a pious Puritan community were to conduct themselves. Bradford proceeded to confiscate the gamesters’ balls and bats. It was not fair, he insisted, that some played while others worked. If they wanted to spend Christmas praying quietly at home, that was fine by him; “but there should be no gaming or reveling in the streets.” (p. 128)

For the Pilgrims, Christmas was a day just like any other; for most of the Strangers from the Fortune, on the other hand, it was a religious holiday, and they informed Bradford that it was “against their consciences” to work on Christmas. Bradford begrudgingly gave them the day off and led the rest of the men out for the usual day’s work. But when they returned at noon, they found the once placid streets of Plymouth in a state of joyous bedlam. The Strangers were playing games, including stool ball, a cricketlike game popular in the west of England. This was typical of how most Englishmen spent Christmas, but this was not the way the members of a pious Puritan community were to conduct themselves. Bradford proceeded to confiscate the gamesters’ balls and bats. It was not fair, he insisted, that some played while others worked. If they wanted to spend Christmas praying quietly at home, that was fine by him; “but there should be no gaming or reveling in the streets.” (p. 128)

This highly disciplined lifestyle was not a fluke but a consequence of the Pilgrims’ attempt to literally follow Paul’s admonition “come out among them, and be separate.” The Pilgrims (aka Separatists) were Puritans who believed that the Church of England was not a true church of Christ. In light of this they believed they needed to form their own church of visible saints. This quest for a pure church required not only a disciplined lifestyle based on the Bible but also the excommunication of those who strayed from the path of righteousness. (See Philbrick p. 12)

The Geneva Bible and the City on a Hill

The Cambridge Geneva Bible of 1591 was the edition carried by the Pilgrims when they fled to America. As such, it directly provided much of the genius and inspiration which carried those courageous and faithful souls through their trials, and provided the spiritual, intellectual and legal basis for establishment and flourishing of the colonies. Thus, it became the foundation for establishment of the American Nation. (Emphasis added; Source: Studylight.org)

When the Puritans’ attempt to reform English society was stymied, a renewed attempt was made in the New World. Puritan New England was not so much a retreat as it was a utopian quest. The Puritans believed themselves to be God’s elect like Old Testament Israel. Governor John Winthrop’s seminal sermon “A Modell of Christian Charity” and the imagery of the Massachusetts Bay Colony as a “city upon a hill” that would be a shining example to all the world reflected the confluence of federal theology’s emphasis on the church as covenanted society and post-millennialist eschatology which anticipated the revealing of God’s glory on earth through his elect nation. Later it would be transformed into the founding myth of the United States of America. (See Robert Bellah’s Broken Covenant, Chapter 1 “America’s Myth of Origin.”)

Recent publicity materials claim the Geneva Bible was the foundational text for Puritan New England. But that was not the case. There were two English bibles used in New England: the Geneva Bible and the King James Version (aka the Authorized Version). It was a common practice for ministers to use the King James Version in their printed sermons in addition to their free rendering of the Greek and Hebrew texts (Note 4, Stout 1982:35).

The presence of the two English translations was consequential for that tiny community. The dilemma of the New England way lay in the attempt to fuse corporate solidarity based on Old Testament theocracy with the Protestant insistence on the salvation of the individual soul by free grace. The Geneva Bible’s commentary notes encouraged a spiritualized reading of Old Testament Israel, while the King James Version’s lack of commentary opened up exegetical space for theocratic readings. The King James Version was more popular in the Bay Colony while the Geneva Bible was more popular among the Pilgrims down in Plymouth Plantation. The Pilgrims’ emphasis on free grace provided them with no cultural glue leading to withdrawal and stagnation (Stout 1982:29; Ahlstrom 1975:186-187). Due to their inability to flourish, the Plymouth colony was made part of the Massachusetts colony in 1691.

The Geneva Bible played a role in the Antinomian controversy that rocked the New England colony from 1636 to 1638. Anne Hutchinson favored the Geneva Bible which allowed for a more spiritualized reading. During the court proceedings she was able to recite verbatim extensive excerpts from the Geneva Bible (Stout 1982:31). Her ally, George Wheelwright, used the Genevan translation of Matthew 9:15 for his controversial Fast Day sermon to trumpet the covenant of grace over the covenant of works (the underpinning of the New England polity).

It has been noted that the Geneva Bible had undergone multiple reprint editions from 1576 to 1644. This raises the question about the cessation of publication after 1644. I suggest that 1644 correlated with the waning enthusiasm for the Puritan Project. The Puritan Project was based on the notion of the church as a covenant community made up of believers able to testify to converting grace. However, a new generation emerged of church attendees unable to testify to a definite conversion experience. The Half Way Covenant was adopted in 1657 as way of accommodating the decline in spiritual fervor of its members and as a way enabling the church to retain influence in society (Ahlstrom 1975:108-110). As religious fervor in New England waned so did the demand for the Geneva Bible. By 1700, enthusiasm for the Puritan project had given way to the more moderate Congregationalism.

By the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, we find a very different America from the one the Puritans knew. While Puritan New England figures quite prominently in the founding myth of the United States, it is important to keep in mind that the source of American democracy is quite complex. It includes the religious tolerance of Roger Williams’ Rhode Island and William Penn’s Pennsylvania, John Locke’s liberal philosophy, Thomas Jefferson’s rationalism, and the more radical views of men like Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin. It is important that we approach history critically even as we affirm God’s sovereignty over human affairs.

The Rise and Fall of the Geneva Bible

The Geneva Bible was at one time the most influential Bible for English speaking Protestants. This was the Bible used by William Shakespeare, Oliver Cromwell, John Knox, John Donne, and John Bunyan. Thus, its influence on English culture was considerable. So why then did it become the forgotten Bible of Protestantism?

The decline can be traced to three factors. One was the lack of official support. The Geneva Bible was produced in the Genevan republic, not in England where the crown was the supreme authority. This republican bias is evident in its commentary that decried tyranny and encouraged revolution against tyranny. For example, the commentary to Exodus 1, especially verse 19, noted the lawfulness of the midwives’ disobedience to Pharaoh. Comments like these were likely to displease King James and his royalist supporters. But there is no evidence of King James ever banning the Geneva Bible. Those who make this assertion seem to have their history mixed up.

Another contributing factor was the growing radicalism of English Puritanism. When it first came out, the Geneva Bible gave very little attention to the concept of covenant and the covenant as the basis for national unity. It was the product of two exiled Englishmen concerned with promoting personal faith in Christ in the face of the Roman Catholic emphasis on salvation through the Church. By the early 1600s England’s break from Rome was more or less an accomplished fact. Attention then shifted to the more ambitious goal of “building an entire social order according to scriptural blueprint” (Stout 19982:25). The growing interest among Puritans in covenant theology (federal theology) from late 1500s to the 1600s began to feed into their desire to reform all of English society in accordance with Scripture. The Geneva Bible’s spiritualizing interpretation of Old Testament passages did not support their emphasis on national covenant. This led, not to its repudiation, as to a quiet neglect by the Puritans.

A third factor was the growing popularity of the King James Version. As a result of the growing tensions between the Puritans and the more mainstream Anglicans, the Hampton Court conference was convened. As a result of this meeting King James authorized a new translation that would be known as the King James Version. Unlike the Geneva Bible, the King James Version of 1611 was very much a corporate venture. It was produced under the sponsorship of the monarch and involved the finest Anglican and Puritan scholars of the time. It contained no marginal commentary and only the barest summary of the chapter contents. As part of the ‘Establishment’ at the time, the Puritans had no difficulty accepting the King James Version. Stout notes:

A third factor was the growing popularity of the King James Version. As a result of the growing tensions between the Puritans and the more mainstream Anglicans, the Hampton Court conference was convened. As a result of this meeting King James authorized a new translation that would be known as the King James Version. Unlike the Geneva Bible, the King James Version of 1611 was very much a corporate venture. It was produced under the sponsorship of the monarch and involved the finest Anglican and Puritan scholars of the time. It contained no marginal commentary and only the barest summary of the chapter contents. As part of the ‘Establishment’ at the time, the Puritans had no difficulty accepting the King James Version. Stout notes:

It is not coincidental that the Puritan leaders’ preference for the Authorized Version grew in direct proportion to their growth in numbers and influence (p. 26).

The King James Version surpassed the Geneva Bible in popularity among the Puritan clergymen (Stout 1982:25). This is no surprise given the fact that many Puritans were involved in the making of the King James Version and its outstanding literary style.

Conclusion

The Puritan Project represents an aspect of English Protestantism. But it is important that we do not exaggerate its importance. It flourished from 1570 to 1640 then went into decline. It was replaced by Congregationalism, Unitarianism, revivalism, not to mention the Baptists and Arminians. So while the Geneva Bible played an important role in English Protestantism, its influence would later be eclipsed by the King James Version. Where Geneva Bible was particular to Puritanism, English speaking Protestantism would be more closely identified with the King James Version.

The King James Version became the most popular Protestant version in America until the twentieth century when newer versions like the Revised Standard Version and the New International Version began to challenge its primacy among Protestants.

There is not a little irony in the fact that Christians in the free church tradition like the Baptists are among the fiercest defenders of the King James Version overlooking the fact that their preferred version was sponsored by a monarch who persecuted the Nonconformists! Given modern Evangelicals’ resemblance to Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams one would expect them to prefer the Geneva Bible. There is also irony in the fact that some neo-Reformed who favor dominion theology also favor the Geneva Bible. If anything, they should be favoring the King James Version like their seventeenth century Puritan predecessors did.

Therefore, church history is not as simple as the promoters of the Geneva Bible make it out to be. It is full of surprising twists and turns, not to mention ironic reverses!

Robert Arakaki

Next: The Geneva Bible compared against the Orthodox Study Bible

References

Ahlstrom, Sydney E. 1975. A Religious History of the American People. Image Books.

Bellah, Robert N. 1975. Broken Covenant: American Civil Religion in Time of Trial. The University of Chicago Press.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. 2006. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War. Penguin Books.

Stout, Harry S. 1982. “Word and Order in Colonial New England,” in The Bible in America (pp. 19-37), Nathan O. Hatch and Mark A. Noll, eds. Oxford University Press.

Recent Comments