Folks, I often get questions about how Orthodoxy views sola fide. Orthodoxy believes that we are justified through faith in Christ, but it denies the Protestant insistence that justification is by faith alone. My assessment is that Martini’s article shows how the Orthodox understanding of justification is much more faithful to Scripture than Luther’s. Let’s read it and have and have a discussion on this important issue. Robert

Saint Paul and the “Works of the Law”

A great emphasis in the protestant reformation was the doctrinal formulation of “justification by faith alone,” which many asserted to be “the doctrine upon which the Church stands or falls” (Martin Luther: “articulus stantis et cadentis ecclesiae”).

While this was in and of itself a complete novelty (and devoid of Patristic warrant or justification) — supposedly based upon the Scriptures alone — it is quite easy to demonstrate that not only is this concept foreign to the Scriptures but also foreign to the first century Judean mindset (not to mention the Christian mindset). To be plain, Luther and other reformers were reading their contemporary disagreements with the mainstream Latin church into the words of St Paul.

From an Orthodox perspective, there is no conflict between faith and works, and indeed the “faith vs. works” arguments never found any foothold in the Christian east. Concepts like “legalism” are a complete non sequitor for the Orthodox, as “merit” has no place in our Theology (but this is a much longer, and more intricate discussion beyond the scope of this post). Perhaps the best summary of the Orthodox viewpoint on this topic is found in Saint Mark the Ascetic (Philokalia): “Some without fulfilling the commandments think that they possess true faith. Others fulfill the commandments and then expect the Kingdom as a reward due to them. Both are mistaken.”

As Christians, we are most certainly “justified by faith” (Rom. 5:1) as the apostle clearly intimates, but this is not the same thing as being justified “by faith alone.” The only time we read “by faith alone” in the Scriptures is when the Brother of God writes: “You see, then, that one is justified by works, and not by faith alone” (St James 2:24). The person who has faith is seen as on par with the demons, but nothing more (according to St James). Our faith must be shown forth and proven by good works — by hope, love, charity, fasting, worship, etc — by coming together as the Body of Christ and offering ourselves, along with Christ, as a sacrifice for the Life of the World.

But the main issue with the novel readings of the reformers (Luther, especially) is that they imported the discussions around “faith working through love” (Gal. 5:6) into St Paul’s completely separate discussions on the “works of the law” (εργων νομου), or what could properly be translated “works of the Torah,” given the Alexandrian (Septuagint) usage of νομος.

Interestingly enough, this phrase “works of the law” is found in only three places in all of Second Temple and early Christian (apostolic) literature. Two of those references are the apostle Paul himself, in his epistles to both the Romans and the Galatians:

“… by works of the law, no flesh will be justified in his sight” (Rom. 3:20)

“Therefore, we maintain that a person is justified by faith apart from the works of the law. Or is God the God of the Jews only? Is he not the God of the Gentiles as well?” (Rom. 3:28-29)

“… no one is justified by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ […] that we might be justified by faith in Christ, and not by the works of the law, because no one will be justified by the works of the law.” (Gal. 2:16)

“I just want to hear this from you: did you receive the Spirit by the works of the law or by believing what you heard? Are you that senseless that having begun in the Spirit, you now end in the flesh?” (Gal. 3:2-3)

“… those who depend on the works of the law are under a curse …” (Gal. 3:10)

Try to imagine how someone 2,000 years from now — and completely removed from our culture by time — would understand a phrase like “Honest Abe.” Without knowing the cultural significance behind a phrase like this, one would be left scratching their head. Similarly, we must listen to the Mind of the Church and the understanding of those living in Paul’s day in order to see what he’s “getting at” in both of these epistles.

I would also be remiss if I didn’t mention here the important notion that Paul’s epistles were not doctrinal treatises “out of the blue,” but were all written to address problems in the Church. These letters are not exclusively (or even primarily) for the sake of posterity and for the establishment of “dogma,” but are rather mostly for the purpose of correcting errors in both thought and behavior in the new and burgeoning pioneer faith of the Christians.

That said, let’s take a closer look at the apostle’s statements above regarding the “works of the law.”

In the first quote from Romans (3:20), St Paul says that “no flesh” will be justified in God’s sight. He then continues to speak of the fact that “there is no distinction” (v. 22) of persons before God, speaking to the difference (or lack thereof) between Jews and Gentiles. The conclusion of the apostle’s present discussion is that the Lord is “God of the Gentiles as well” and therefore “a person is justified by faith apart from the works of the law” (Rom. 3:28-29). In other words, we are not purified before God because of “Jewishness” or cultic purity (as the Pharisees and other anti-temple cults of Second Temple Judaism argued, e.g. the Essenes/Qumran community), but because of the faith of Abraham — because of faith in Jesus Christ. It is Christ that makes us pure through our union with Him (and as a result, the entire world is both purified and sanctified by the Church and Her sacrificial service).

The issue that the apostle is addressing here is not one of “faith vs. works” or even “legalism” vs. “faith alone” — the question is, does one need to “become a Jew” first in order to be a true and justified Christian? The answer is (of course) no, for Christianity is the true Judaism. There is not even a hint of the Medieval and protestant notion of “meritorious works” here, and to read such a discussion into Paul is simply anachronistic.

In the Galatian epistle, St Paul makes the same argument in relation to εργων νομου, but with even more force — even challenging the apostle Peter on this very issue in front of a large gathering of Christians (although Chrysostom seems to indicate that they planned this public outburst in advance, in order to teach a lesson).

The apostle emphasizes that he and other Hebrew Christians are “Jews by nature and not Gentile sinners” (Gal. 2:15). This statement immediately characterizes the following ones in the context of “Jews vs. Gentiles,” not “faith vs. works” as later protestant commentators would erroneously assert. The apostle then helps me not feel so bad for being redundant at times (i.e. v. 16) and reinforces that one is justified through “faith in Jesus Christ” and “not by the works of the law.” For Christians, our “cultic purity” as people of the true Temple is found through our union with Jesus Christ, not through the “traditions of men” (St Mark 7:8) that would have us continually purify ourselves by other means (more on that in a bit).

Shifting the focus to that of “receiving the Spirit” of God, the apostle asks the Galatians if this was accomplished through εργων νομου or through belief — the answer is obvious: throughbelief, and then continued through faithfulness to the Lord Jesus Christ. Furthermore, if we have “begun in the Spirit,” why would we nullify the Grace of God with the εργων νομου and purification of “the flesh?” This, again, is not a reference to “meritorious works” or “works of supererogation,” but to that of cultic purity and the excesses certain groups propagated in the later period of the Second Temple.

When we consider the old covenant Scriptures with regards to the Temple and ritual purity, we can see how the “flesh” (σάρξ or sarx) was a pivotal theme — but one that had nothing to do with “merit.” For example, in Leuitikon (Leviticus), chapters 13-14, there are various instructions on how to deal with people that contract the flesh-disease of leprousy. The fact that these people are anointed with oil is no insignificant notion, as the correspondance to Chrismation reminds us that through union with Christ (and by receiving the Holy Spirit), we are united to the true Temple (Jesus Christ) and are therefore made ritually pure in the flesh. Beyond this, we see that even buildings can contract leprousy, being defiled by the Gentiles (the foreigners) that dwelled in the land before the Hebrews:

“When you come into the land of the Chananites, which I will give you in possession, and I shall give a leprous disease in the houses in the land acquired by you […] And he[the priest] shall look at the attack in the walls of the house, hollow, greenish or reddish […] and they shall take out the stones in which is the attack and throw them into an unclean place outside the city. And they shall scrape off the inside of the house round about and pour out the soil in an unclean place outside the city.”

Leuitikon (Leviticus), 14:34,37,40-41 (LXX)

This same concern for a ritual purity “of the flesh” was paramount in the notions of both the Pharisees and the other anti-Temple/anti-Jerusalem movements of the first century — not “faith vs. works.”

Due to the fact that “the promised land” had been under constant occupation by “the Gentiles” (the Assyrians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Babylonians, etc.) — along with the continual defilement of the Temple by these impure foreigners — the feeling of ritual impurity had to have been at an all time high for those living in the first century (AD). In the minds of the Pharisees and Essenes, the entire land was defiled in the flesh with leprousy. The only hope for the Judeans, then, was the purification of their land and of their Temple (or even an abandonment of the Temple altogether, until it was under the control of “pure” hands). Without the Temple as a locus of cultic purity — in the midst of a purified land, set apart for God’s people — there was no hope for the salvation and restoration of Israel (the eschatological hope for the new covenant, the anointed one, or Messiah, etc.).

Salvation must be seen (in one sense) as a return to the Paradise of Eden, in true union and communion with God — but this can only be possible if we are cleansed of our impurities and able to dwell in the midst of a holy God (or rather to have a holy God dwell in the midst of us). The concern of the Pharisees and Essenes (for example) was certainly valid, therefore, but they were ultimately “missing the boat.”

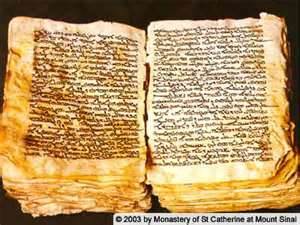

The third place where this phrase ”works of the Torah/law” is found is in one of the documents of the Dead Sea Scrolls (from Cave Four). This scroll is self-titled Miqsat Ma‘ase ha-Torah, or “Selections of the Works of the Torah” (it is also known as 4QMMT/4Q394-399 in scholarly references or as “A Sectarian Manifesto”).

The scroll opens with a statement of purpose: “These are some of our pronouncements concerning the Law of God; specifically, some of the pronouncements concerning works of the law, which we have determined . . . and all of them concern defiling mixtures and the purity of the sanctuary” (4Q394 Frags. 3-7, Cols. 1-2; with 4Q395 Frag. 1). As stated here, the very purpose of these εργων νομου are to keep the sanctuary pure and free of defilement — they are not about “meriting” salvation through “good works.”

Some of the “works of the law” that are then enumerated fall under topics such as: a ban on offerings using Gentile grain, a ban on sin offerings boiled in Gentile/copper vessels, a ban on sacrifices by Gentiles, rulings on the purity of those who prepare the red heifer, a ban on bringing the skins of cattle/sheep into the Temple, a ban on Temple entrance after contact with skins of a carcass, a ruling on who is fit to eat of the holy gifts, a ban on the inclusion of the “unfit” into the people of Israel, a ban on the entrance of the blind/deaf into the Temple, a ruling on the cleansing of lepers, a ruling on unlawful sexual unions and marriage, and so on (cf. The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation, ed. Wise, Abegg & Cook, pp. 454-462). As you can tell, the predominant concerns of these “works of the law” is that of cultic/ritual purity (as related to the Temple and to the people/congregation of Israel).

But beyond this, what is the ultimate concern? As alluded to above, it is that of salvation — and not just for individuals but for the whole of Israel (the longing for its restoration and salvation in the new covenant, even).

The “people of the desert” in Qumran are warned that to ignore these rituals of purity is to invite the judgment of God: “. . . because of […] the fornication, some places have been destroyed. Indeed, it is written in the book of Moses that ‘You shall not bring an abomination into your house,’ for an abomination is hated (by God).”

You can almost hear the paranoia in these words, as the Judeans looked around and were completely surrounded and “infested” throughout the land (and the Temple) by Gentiles. It is no wonder that a variety of anti-Temple movements arose in the first century (of which the Forerunner, John the Baptist, was likely a part), and one can’t help but mention the zeal shown by Christ in the cleansing of the Temple. In fact, the necessity of “separation” from the impure is next mentioned in this scroll: “We have separated from the majority of the people and from all their uncleanness and from being party to these matters or going along with them in these things. And you know that no unfaithfulness, deception, or evil are found in our hands, for we give some thought to these issues” (4Q398, Frags. 14-17, Col. 1).

The connection of this apparent apostasy and compromise in Israel is connected with an eschatology of “the Last Days,” as well: “In the book of Moses it is written […] that you ‘will turn from the path and evil will befall you.’ And it is written ‘that when all these things happen to you in the Last Days, the blessing and the curse, that you call them to mind and return to Him with all your heart and with all your soul.’ . . . at the end of the age, then you shall live . . .“ Even with some damage and incompleteness to these fragments, we can see the overall direction the author of the scroll is taking — if the defilement and cultic impurity of Jerusalem/the Temple continues, God will completely abandon Israel. The time for returning to God “with all your heart and with all your soul” has come (and arguably, this is what we see in the new covenant and in the Person of Jesus Christ and His Church).

Continuing with the eschatological theme, the Qumran community (according to this scroll) expected the restoration of Israel (the return to God) to occur in “the Last Days”: “… when those of Israel shall return to the Law of Moses with all their heart and will never turn away again.” I believe this refers not only to the new covenant but explicitly to the ultimate anti-Temple sect: “the Way” of Jesus Christ and His blessed apostles.

The rather important conclusion to this scroll (“Selections of the Works of the Torah”) is as follows:

“Now, we have written to you some of the works of the Law, those which we determined would be beneficial for you and your people, because we have seen that you possess insight and knowledge of the Law. Understand all these things and beseech Him to set your counsel straight and so keep you away from evil thoughts and the counsel of Belial. Then you shall rejoice at the end time when you find the essence of our words to be true. And it will be reckoned to you as righteousness, in that you have done what is right and good before Him, to your own benefit and to that of Israel.”

Of note, we see that the ultimate purpose of these “works of the law” is for the sake of Israel and her salvation. For the Judeans of Qumran, this had come to mean purifying the land and the Temple from the defilement — the leprousy — of the Gentiles, and this is certainly why they found themselves in the recesses of the wilderness as a protest against the impure and compromised priests of Jerusalem.

It seems to be the case as well that the Pharisees had ultimately the same goal, leading them to push for cultic purity even outside the context and walls of the Temple (an extra-Scriptural notion), as we must keep in mind that the Pharisees were not priests, nor were they directly connected to the (Second) Temple. Rather, they were attempting a “lay” reform of the priesthood and of the people of Israel, pushing their agenda by any means necessary (as an aside, this made the “new Rabbi on the block” — Jesus — to be quite a direct affront and competitor against their efforts, and thus their attempts to discredit him and his ministry).

I also need to mention the use of the phrase “reckoned to you as righteousness” in this scroll. In the Qumran/Essene/Pharisee mindset, the ultimate personification of this being “reckoned” as righteousness is not in Abraham, but in Phinehas (and this is very clear in theDSS elsewhere). Phinehas is famous for his zeal in the book of Numbers:

“And Israel stayed in Sattim, and the people were profaned by whoring after the daughters of Moab. And they invited them to the sacrifices of their idols, and the people ate of their sacrifices and did obeisance to their idols […] And behold, a man of the sons of Israel came and brought his brother to the Medianite woman before Moyses [Moses] and before all the congregation of Israel’s sons […] And when Phinees[Phinehas] son of Eleazar son of Aaron the priest saw it, he arose from the midst of the congregation. And he took a barbed lance in his hand, and he went in after the Israelite man into the alcove and pierced both of them, both the Israelite man and the woman through her womb. And the plague stopped from Israel’s sons. And those that died in the plague were twenty-four thousand.”

Numbers 25:1-2; 6-9 (LXX)

The zeal shown here by Phinehas was that of keeping the congregation of Israel pure, and helping to stave off further spread of a plague (judgment for their “whoring” as the LXX nicely puts it). In the same way, both the Pharisees and Essenes (and presumably the community at Qumran) were zealous for the absolute purity of Israel. As a result, they associated their actions with those of Phinehas the priest. And indeed, the approval of this zeal is seen in the Psalmist’s words: “And Phinees stood and made atonement, and the breach abated. And it was reckoned to him as righteousness to generation and generation forever” (Psalm 105[106]:30-31 LXX).

If we circle back to the words of St Paul in his two occasional epistles referenced above, everything should be much clearer (although I would argue that the Scriptural text itself stands alone to delineate against any notion of “faith vs. works” or meritology). What’s interesting, however (cf. N.T. Wright), is that St Paul extends the “works of the law” to be not only these cultic purity laws of the Temple but also that of the most basic of Judean “markers,” such as circumcision itself (e.g. Romans 2:25-29; 3:30; 4:9-13). The heart of the apostle’s arguments in both Romans and Galatians is not “faith vs. works” but rather “you don’t have to become a Jew in order to become a Christian.” Indeed, to be a Christian is to be united to Christ — and that is a promise offered to the whole world, for “there is no distinction” (Rom. 3:22) with God.

At the same time, we also see the contemporary (for the apostle) concern over cultic purity in St Paul’s letters. For example, when the apostle mentions being justified “in the flesh” in both letters (e.g. Rom. 3:20; Gal. 3:3), he is not speaking to the reformers’ notion of “faith vs. works” (i.e. “works” are “good works” done “in the flesh” and not “by the Spirit”) but rather the attempt to be ritually pure before God through the “works of the law.” This is corroborated not only by the Dead Sea Scrolls but also in Leuitikon (Leviticus, Ch. 13-14), where we see that both people and various objects (e.g. homes) can be diseased “in the flesh” with leprousy, becoming ritually impure in God’s sight.

A great promise of the new covenant in Christ — as related to this subject — is that Christ has replaced the Temple in His very Person. As a result, the Church (as the Body of Christ) is also the temple of the living God, which St Paul mentions elsewhere. With the Church now supplanting the Temple everywhere it gathers, the purity of Christ is capable of being spread throughout the world, ridding every nation of the defilement of the flesh and of every strain of leprousy.

While the Essenes and the Pharisees were both correct in wishing to purify Israel from defilement, they were also both incorrect as to how this would be accomplished.

With the destruction of the Temple in AD 70, the promise of Jesus to supplant that Temple in the Holy Gospel finds its ultimate realization, and the “Last Days” had truly come upon Israel. In Christ, and in the apostolic Church, the people of God had now “returned to God,” and through union with Christ and faith in Him are now truly pure — even without circumcision and even without the “works of the law.” In other words, even without the old Temple and even without becoming Jewish first.

In this sense, then, the Good News of Christ is truly Good News for the whole world — for the Jew first and also the Gentiles (the “nations”). The so-called “Great Commission” is a calling to spread the purity of Christ — the true Temple — to all the nations; and this purification begins in the purifying waters of Baptism (cf. St Matt. 28:18-20), hearkening back to the purification rituals for leprousy (using water and oil) in the books of Moses.

The debate over the “works of the law” in the first century was not one over “faith vs. works,” but rather over how one is made a Christian, and therefore how the entire world can be saved in Christ. This mission will certainly require our good works, as we cooperate with the Grace of God and work to spread the Good News and the purity of Christ to every corner of the earth through the ministry of the Church.

On Behalf of All.org

Recent Comments