Tell me the history of the church and I can tell you your theology.

Church history is not neutral but is shaped by our theological beliefs. This is especially the case with Emperor Constantine:

- to many Evangelicals and Anabaptists Constantine was the arch villain who caused the early Church to fall from its apostolic purity,

- to mainstream Protestants and Roman Catholics Constantine was a pivotal historical figure who made Christianity into a public religion,

- to Eastern Orthodox Christians he is Saint Constantine “equal to the apostles.”

Defending Constantine by Peter J. Leithart is more than a biography of Constantine the Great. It starts off as a theological history and ends as an attempt to construct a political theology. Leithart draws upon a wide range of scholarship to present the reader with a fine grained and nuanced understanding of Constantine the man and the consequences of his embrace of Christianity.

Pastor Leithart’s underlying motive for writing this history is to refute John Howard Yoder‘s radical Anabaptist political theology. This stream of Protestantism holds that the church is a community of faithful believers who renounce all worldly power and adheres to pacifism. This position leads Yoder to the position that Constantine never truly converted to Christianity and that the Christian church he allied himself with was a fallen, compromised church (see Leithart pp. 252-254; 305-306). By refuting Yoder, Leithart intends to present Constantine as a model for Christian political practice.

The purpose of this review is not just to assess Leithart’s book but also to comment on some of his ideas from the standpoint of an Eastern Orthodox Christian.

Constantinian Paradigm

Constantine’s historical significance lies in his embrace of Christianity which laid the basis for the Constantinian paradigm. This is the belief that Christianity has a rightful place in the public sphere and that the church has an obligation to bring Christian moral values to the family, society, and politics. Similarly, the Constantinian paradigm views Christian clergy as public leaders and allows for the use of state resources to support the church. This alliance which began with the Edict of Milan in 313 would frame Western society and politics until the 1800s and 1900s. The Constantinian paradigm began to be displaced by the Enlightenment which gave rise to non-theistic systems of thought like Communism and Rawlsian liberalism.

Constantine matters to Reformed and Orthodox Christians because both traditions rely on the Constantinian paradigm. Important to Reformed theology is the belief that the call to reformation extends not only to the church but to society as well. This is apparent in the last chapter of Calvin’s Institutes “Civil Government” (Book 4, Chapter XX). While Reformed Christians might agree with Yoder on the fall of the church, they would disagree with his view of the church as a pure community of disciples removed from society.

Eastern Orthodox Christians will likewise take issue with Yoder’s political theology, especially with the assumption of the fall of the church. The Orthodox Church believes that it has maintained an unbroken chain of apostolic succession going back to the original apostles. Furthermore, Orthodoxy holds to the doctrine of symphonia — the doctrine of church and state distinct from each other but working in harmony.

Leithart does the Christian community a great service with his discussion of the historical origins of the notion of the fall of the church (p. 307). He shows how Yoder’s allegations that Constantine corrupted the church rests on poor history (p. 317-321). Leithart shows that Yoder’s flawed church history leads to a defective theology. His critique of Yoder’s historiography demonstrates the aphorism stated at the outset of this blog posting: Tell me the history of the church and I can tell you your theology.

Discipling the Nations

Constantine was not the first emperor to issue edicts of toleration. What distinguishes him was his turn away from Roman paganism and his supportive attitude towards Christianity. When Constantine defeated Maxentius and entered Rome as victor, rather than follow the conventions which stipulated that the victor enter the Capitolium and offer sacrifice to Jupiter, he refused (p. 66). This marked an epochal shift in Rome’s political culture. Constantine’s outlawing of the gladiatorial shows reshaped Roman culture. It in effect shut down a key means by which the populace were instructed in the values of violence and martial glory (Leithart p. 304).

In embracing the Christian cause Constantine did not relinquish the power of the sword. He continued to engage in military campaigns and he continued to engage in political intrigues characteristic of any political elite. His refusal to abandon the powers of the state is a disappointment to those who hold an Anabaptist political theology.

Another momentous decision by Constantine was the founding of Constantinople, the New Rome (pp. 119-120). This decision was rooted in Constantine’s desire to raise up a new metropolis built from a Christian foundation. The old Rome, the traditional center of power, was deeply stained by its pagan past. From the standpoint of political theology the establishment of Constantinople reflected the belief in the possibility of a Christian civilization. This can be traced to the call to disciple the nations in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19-20) and in the eschatological vision of the New Jerusalem in Revelation. The radical Anabaptist tradition disavows the possibility of the Christianization of societies and holds instead to the idea of a Christian counter culture marked by ethical purity and pacifism.

There is a certain paradoxical quality to the attitudes that Eastern and Western churches hold towards Constantine. In the Western tradition Constantine is more of a remote historical figure, yet there has been considerably more discussion about the Constantinian paradigm, i.e., how politics ought to be shaped by Christian values. Thus, Leithart’s book is part of a long running debate in the Western tradition. Eastern Orthodoxy venerates Constantine as a saint, but there is relatively little written about political theology in the Eastern tradition.

Constructing a Political Theology

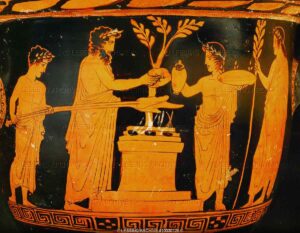

One of the fascinating insights presented by Leithart is his argument that: (1) every ancient city had a sacrificial center, (2) Constantine’s significance lies in his abandonment of the responsibility of attending to the sacrifices expected of Roman emperors, and (3) just as significant his welcoming the church, the city of God founded on the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross (pp. 326-331). Leithart’s political theology juxtaposes pagan Rome against the New Jerusalem, the Church.

He writes:

The church too was a sacrificial city, the true city of sacrifice, the city of final sacrifice, which in its Eucharistic liturgy of sacrifice announced the end of animal sacrifice and the initiation of a new sacrificial order (p. 329).

I found chapter 6 “End of Sacrifice” especially helpful for understanding the way religion and sacrifice permeated pagan Rome and how Constantine’s “conversion” led to the passing of pagan sacrificial system and the ascendancy of the Christian Eucharist as the basis for Western culture. What is striking about this passage is that one can easily see in Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy a resemblance to the sacrificial city described by Leithart, but it is much harder to see this resemblance in the Reformed churches due to the fact that the sermon has displaced the Eucharist in many Reformed congregations. Nonetheless, it should be noted that many Reformed churches still proclaim Christ’s sacrificial death.

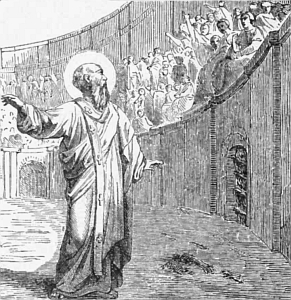

As an Orthodox Christian I would like to point out the role of the early martyrs in the evangelization of the Roman Empire. The ancient polis rested on the civic liturgy, i.e., public officials offering up sacrifices to the gods to ensure the well being of the city. The ancient Christians attacked the ancient sacrificial system through two means: (1) the proclamation of the Good News of Christ’s death and resurrection, and (2) their willingness to sacrifice their lives for the Gospel of Christ. The inability of the authorities to cow the Christians like Polycarp into offering up the traditional sacrifices meant the end of the pagan religions.

Leithart asserts that Constantine provides a model for Christian political practice. As much as I’d like to support Leithart in this there are a number of questions that need to be raised from an Eastern Orthodox perspective. One is that Constantine was a catechumen for much of his adult life and was not baptized until shortly before his death. The significance here is that he was able to rule with a relatively free hand executing members of his household without fear of excommunication. The first Christian emperor was Theodosius who was baptized shortly after he became emperor. It was only because Theodosius had been baptized that Bishop Ambrose of Milan was able to threaten him with excommunication over the massacre of 7000 in Thessalonica in 380. The sacrament of baptism effectively brought the most powerful man in the Roman Empire under the authority of the Church. It would have been good for Leithart to have qualified his touting Constantine as a role model for Christian politics by presenting him as providing the beginning of a social template and by including other notable Christian rulers, e.g., Justinian the Great in the East and Charlemagne in the West.

Post-Constantinian Society

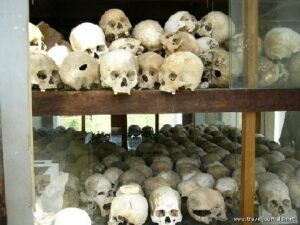

In the subsection “There Will Be Blood, Again” (pp. 340-341), Leithart discusses the implications of a post-Constantinian society. He asserts that when the modern state excludes the church, it has no moral brakes to speak of and instead seeks to be “resacralized” by other means (p. 340). This is a point that needs to be explored through a discussion as to whether or not the Nazi Holocaust, Mao’s Great Leap Forward, Pol Pot’s killing fields, and the so-called “right” to abortion are modern equivalents to ancient ritual offerings to the gods. Leithart’s suggestion of a grim nihilistic future politics is something that Christians need to take seriously. “There Will Be Blood” is a fascinating discussion of modern politics and if I have a criticism it is that it is far too brief. Only two pages?!

Conclusions and Findings

In this reviewer’s opinion Leithart’s critique of Yoder’s Anabaptist political theology is like fighting yesterday’s war. He touches on modern politics in just the last few pages of the book (pp. 340-341). Hopefully, Leithart will be writing more on this important subject matter.

Any attempt to construct a Christian political theology needs to study Constantine’s impact on the church’s role in society. Without question, it is Constantine who made Christianity into a public religion. Much of American political history, e.g., the Moral Majority, the Prohibition, the Abolitionist movement, the Puritan Commonwealth all assume the Constantinian paradigm. The widespread influence of anti-Constantinianism has impeded the ability of Christians to scrutinize Christianity’s role in modern society. It has also prevented many Christian leaders from understanding the significance of the recent move away from the Constantinian paradigm in America.

Reading Defending Constantine has made me conscious of a significant difference between Western and Eastern Christianity. Where the West has had a long continuous history with the Constantinian paradigm, Eastern Christianity has suffered numerous disruptions, e.g., the Muslim conquests of North Africa, the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 and the Bolshevik Revolution in 1918. However, with the Greek War for Independence in the 1820s and the fall of Communism in the late 1980s we see attempts being made to bring back some form of the Constantinian paradigm in Russia and in the Balkans with results that can be disconcerting for Westerners schooled in Lockean liberalism. My impression is that American Protestants and Roman Catholics are much more comfortable speaking up in the public square and theorizing on Christians’ role in politics than the Orthodox. This can be seen in Liberation Theology in Roman Catholic circles and Christian Reconstructionism in Protestant circles. Orthodoxy in America has been much more reticent in its public witness despite its doctrine of symphonia. It has yet to match the literary output of Christian political thinkers in the West. There is much Christians from both the Reformed and Orthodox traditions can learn from Constantine. Leithart has done us a great favor by critiquing the anti-Constantinian prejudice widespread in American Protestantism and his presenting Constantine as a model for political theology.

Robert Arakaki

Robert,

This is a wonderful exposition. It has made me want to read the book.

I have, in the past, come from a modified Yoderian stance (even though I am Reformed). Lots of issues I’m still searching through, so this book will help to clarify and maybe even correct my thoughts.

Might I suggest a book to review for the site? Rodney Stark’s The Rise of Christianity details a number of the things you’ve brought up, is written by a Protestant (although he wasn’t a Christian when he started the book), and really is eye opening about the role of martyrs and hospitality as opposed to evangelism in the conversion of the Roman Empire. I’d love to hear an Orthodox take on the book. It changed the way I viewed the Church (it made me rethink my previously negative stance towards the Church Fathers — I basically abandoned the “Fall from Purity” understanding I had).

Russ

Russ,

I’m glad you liked the review of Leithart’s book. And thanks for the suggestion of Rodney Stark’s book. I read his “Theory of Religion” when I was in a study group for sociology of religion years ago and happened to like it.

Robert

Besides being a fine scholar, thinker, writer, and good man, Pastor Peter Leithart is a friend of mine. So I was predisposed to enjoy this book before I read it, as I have several of his other books (like Deep Comedy, http://www.amazon.com/Deep-Comedy-Trinity-Tragedy-Literature/dp/1591280273/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1328401317&sr=8-1.) Defending Constantine is excellent and stimulating — though Robert’s review was surprisingly kind. I guess I suspected a bit more of an edge at spots.

Though I’d heard much about Yoder, I admit over the past decade I’ve wondered a good bit IF “Christian Pacifism” every had a place to rest within Just War theory. (guess those Lawrence Vance articles on lewrockwell.com have had some effect). It’s hard to imagine how Just War Theory could have been tinner tissue paper restraining Modern “Protestantism” in the West the past 152 years! It seems to me that it would be far too easy for a modern neoconservative to read Peter’s book and come away believe Constantine in his camp — which is something I doubt seriously. Of course Peter doesn’t say this all, and that perhaps points to one recurring problem. I’d quarrel with very little with what Peter does say very well in Defending Constantine. It’s what he fails to say that sometmes disappoints. He could easily flesh out his implications and also prevent other faulty assumptions…if he only would. I too would have loved much more on modern day implication for both Church and State.

I second the suggestion for an Orthodox review of The Rise of Christianity. I felt Stark did a wonderful job of explaining and presenting his case. I also loved the insights coming from a sociological and not merely historical or theological perspective. I knew nothing about the author when I picked up the book at my local library, but he sounded like some species of believer, so thanks, Russ, for that little tidbit about his background. Thanks also, Robert, for this review of Leithart’s book.

Another question:

Why do the Orthodox consider Constantine a saint? He didn’t become a son of the Church until very late in life (deathbed) and did many evil things while he was a Catechumen (I doubt Hippolytus would have let him in!).

My real question is this: what makes one a saint in the Orthodox tradition? In my Protestant understanding of Catholicism (in other words, I may very well be wrong here), to be a saint requires a holy ascetic life and at least two miracles. How about Orthodoxy?

Thank you, in advance, for increasing my understanding.

Russ

Russ,

Good questions! Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism have quite different processes for recognizing people as saints. The Roman Catholic Church takes a more bureaucratic and institutional approach. There are precise criteria that must be met and verified before the Pope canonizes that person. With Orthodoxy the process is less bureaucratic and more community based. Oftentimes it is the laity who recognize a person to be a saint and the hierarchs follow them. The Orthodox approach is more mystical/organic than Roman Catholicism. A local church may recognize someone as a saint, then a regional church, then the church as a whole.

Key to the process is reception. A hierarch must receive the opinion of the laity that so-and-so is a saint, likewise a neighboring diocese or patriarchate must receive the opinion of a neighboring jurisdiction that so-and-so is a saint. In Orthodoxy when someone is recognized as a saint the church commissions an icon of that saint, composes a song (troparion) in memory of the saint, and enters the saint’s name and the death of his/her passing into the liturgical calendar. You might be wondering if all this is biblical. I would say that one can see a similar process of discernment in the Bible. The great roll call of the faithful in Hebrews 11 was not invented by the author of Hebrews but reflects a general consensus of the Jewish and Christian faithful.

One could say that saints are the heroes of the faith. The Church holds them up to us as role models to emulate. In the case of Constantine the Church honors him for his efforts to advance the spread of the gospel in the Roman Empire and for that reason named him “Equal to the Apostles.” This title has been given to other Orthodox saints as well. I would say that even Protestants have saints. For example, the Southern Baptists have the Annie Armstrong Easter Offering and the Lottie Moon Christmas Offering. The two collections draw upon the life and example of these two missionaries to advance the cause of Southern Baptist missions. Among conservative mainline Protestants many churches celebrate the life and ministry of Martin Luther on Reformation Sunday. Among liberal Protestants the life and example of Martin Luther King Jr. is a powerful inspiration and model. In Hawaii, we honor the life and work of Fr. Damien by his statue at the state Capitol. When I was a Protestant, I greatly admired (and still do) the life of Henry Opukaha’ia, a Hawaiian boy, who left Hawaii to study at Connecticut and who prepared the way for the coming of the Congregational missionaries and the Christian message to Hawaii.

Thanks for your questions and I hope the examples of the saints will inspire you to a deeper commitment to Christ!

Robert

Robert,

> not in any particular order . . .

(1) thanks for a good review of Leithart – it encourages reading of the book to appreciate more fully its contents.

(2) may I support the request of Russ for a review of Rodney Stark’s The Rise of Christianity. I purchased it when it first came out and remain impressed on his scholarship here & elsewhere (I have a number of his other books).

(3) re your commencing paradigm:

<>

Can I humbly suggest an additional dot-point that combines elements from (a) & (b) which I will call (a-b), and which predates both (a) and (b):

# to the successors of the Jewish “Jerusalem-Central” Church (of St James the Just) and to the Johannine/Arimathean Celtic Church (which predated Augustine of Aosta), his “canonisation” represented the logical end-point of the unsatisfactory approach of Saul (Paul) of Tarsus towards all things “Classical” (ie Greek & Roman). And an indictment of the distance this Pauline tradition had traveled from Jerusalem to both Athens and Rome.

Constantine’s “canonisation” was required by Emperor Theodosius to justify his “symphonic harmony” theology. Theodosius also had to overlook Constantine’s only undisputed baptism – by the Arian Eusebius of Nicomedia almost on his deathbed.

If one (correctly) regards the Byzantine doctrine of “symphonic harmony” as an anti-Biblical political heresy, and in its context – in total defiance of the counsel of the Prophet Daniel towards all things “Classical”, one is required to regard Constantine’s “canonisation” as a highly political act by a compromised Church strand in the Pauline tradition, to ‘sanctify’:

(i) an essentially unreconstructed Pagan Roman Empire – with its Political, Legal, Constitutional and Military Romanism, and Cultural, Philosophical and Religious Hellenism,

(ii) Constantine’s perversion of the usage of “Catholic” (from Ignatius) into a syncretism between the Pauline “gospel” and all things “Classical” (eg the Church Calendar),

(iii) – inter alia – the use of Pagan Roman troops to maintain Popes Sylvester and Damasus of Rome in office when neither was worthy of the office they occupied,

(iv) ex-post-facto the entire Byzantine theocratic tradition (which extended inter alia, to the Romanovs),

(v) the entire corpus of essentially unsanctified Byzantine novellas regarding Church administration incorporated as ‘canons’ in Ecumenical Councils (when the solely Holy-Spirit-sanctioned Canons of these Councils relate to Trinitarian Theology in its subsets of Patrology, Christology (& hence Mariology) and Pneumatology).

(vi) the entire Byzantine tradition in Constantinople 330-1453.

(etc).

From your review, it would seem that Liethardt has overlooked these issues. If this not the case, it may be worthwhile to expand your review to incorporate these matters.

Disregard Constantine’s ‘canonization’ as legitimate, and all of the above six fall. It would also call into question the legitimacy of the relatively recent ‘canonisations’ of the Romanov Nicholas II & his family in Russian circles.

Hence the all-important questions:

(1) “Quo Vadis Orthodoxy in loc cit above?”

(2) Does otherwise “Holy” Orthodoxy have a blind spot in this regard?

Pax Vobiscum in nominie Patre, et Filli et Spiritus Sanctus.

Robert,

> not in any particular order . . .

(1) thanks for a good review of Leithart – it encourages reading of the book to appreciate more fully its contents.

(2) may I support the request of Russ for a review of Rodney Stark’s The Rise of Christianity. I purchased it when it first came out and remain impressed on his scholarship here & elsewhere (I have a number of his other books).

(3) re your commencing paradigm:

“Tell me the history of the church and I can tell you your theology. Church history is not neutral but is shaped by our theological beliefs. This is especially the case with Emperor Constantine:

(a) to many Evangelicals and Anabaptists Constantine was the arch villain who caused the early Church to fall from its apostolic purity,

(b) to mainstream Protestants and Roman Catholics Constantine was a pivotal historical figure who made Christianity into a public religion,

(c) to Eastern Orthodox Christians he is Saint Constantine “equal to the apostles.” ”

Can I humbly suggest an additional dot-point that combines elements from (a) & (b) which I will call (a-b), and which predates both (a) and (b):

# to the successors of the Jewish “Jerusalem-Central” Church (of St James the Just) and to the Johannine/Arimathean Celtic Church (which predated Augustine of Aosta), his “canonisation” represented the logical end-point of the unsatisfactory approach of Saul (Paul) of Tarsus towards all things “Classical” (ie Greek & Roman). And an indictment of the distance this Pauline tradition had traveled from Jerusalem to both Athens and Rome.

Constantine’s “canonisation” was required by Emperor Theodosius to justify his “symphonic harmony” theology. Theodosius also had to overlook Constantine’s only undisputed baptism – by the Arian Eusebius of Nicomedia almost on his deathbed.

If one (correctly) regards the Byzantine doctrine of “symphonic harmony” as an anti-Biblical political heresy, and in its context – in total defiance of the counsel of the Prophet Daniel towards all things “Classical”, one is required to regard Constantine’s “canonisation” as a highly political act by a compromised Church strand in the Pauline tradition, to ‘sanctify’:

(i) an essentially unreconstructed Pagan Roman Empire – with its Political, Legal, Constitutional and Military Romanism, and Cultural, Philosophical and Religious Hellenism,

(ii) Constantine’s perversion of the usage of “Catholic” (from Ignatius) into a syncretism between the Pauline “gospel” and all things “Classical” (eg the Church Calendar),

(iii) – inter alia – the use of Pagan Roman troops to maintain Popes Sylvester and Damasus of Rome in office when neither was worthy of the office they occupied,

(iv) ex-post-facto the entire Byzantine theocratic tradition (which extended inter alia, to the Romanovs),

(v) the entire corpus of essentially unsanctified Byzantine novellas regarding Church administration incorporated as ‘canons’ in Ecumenical Councils (when the solely Holy-Spirit-sanctioned Canons of these Councils relate to Trinitarian Theology in its subsets of Patrology, Christology (& hence Mariology) and Pneumatology).

(vi) the entire Byzantine tradition in Constantinople 330-1453.

(etc).

From your review, it would seem that Liethardt has overlooked these issues. If this not the case, it may be worthwhile to expand your review to incorporate these matters.

Disregard Constantine’s ‘canonization’ as legitimate, and all of the above six fall. It would also call into question the legitimacy of the relatively recent ‘canonisations’ of the Romanov Nicholas II & his family in Russian circles.

Hence the all-important questions:

(1) “Quo Vadis Orthodoxy in loc cit above?”

(2) Does otherwise “Holy” Orthodoxy have a blind spot in this regard?

Pax Vobiscum in nominie Patre, et Filli et Spiritus Sanctus.

John,

I’m not an expert on Constantine or that period of church history. I will leave your counterpoints to the other qualified experts in the field. You might want to bring up your points with Peter Leithart and engage him on those points. Or you could write your own paper and submit it to a refereed journal. I haven’t come across any authoritative source that made mention of your arguments so your points strike me as being rather novel.

Robert

Russ, there are a couple of other thoughts concerning the Saints that might help. Not all Saints are equal, though they are all honored because Christ worked in their lives in some extraordinary way. Some Saints, such as St. Nicholas of Myra and St. Anthony of the Desert are known for lifelong and remarkable fidelity to the gospel, asceticism and great holiness of life, great compassion, and even miracles, and are very highly honored. Others are Saints simply because they were martyred for their confession of the gospel right before their deaths. The Thief on the Cross who honored Christ and asked to be remembered in His Kingdom is a Saint in the Orthodox tradition. Secondly, we honor those Saints the Church has recognized, but we don’t expect that this includes all who are truly Saints and may, in fact, include some who in God’s eyes are not. God is the only One who fully and truly knows those who will be honored as heroes of the faith in His Kingdom.

“…and may, in fact, include some who in God’s eyes are not.”

I’m not so sure this is true, Karen, though I admit that I could be wrong. Can anyone elaborate more on this? I wouldn’t want to be honoring someone who truly wasn’t a saint.

Thanks,

John

John,

Thanks for bringing this to our attention. I think you’re right on this. I’m in agreement with you on this because in my understanding one of the fundamental expression of Orthodox belief is found in its worship, e.g., the Liturgy and the various services and prayers. The recognition of someone as a saint and their inclusion in the church calendar rests upon the Church, local and catholic, being guided by the Holy Spirit. Where canonization in Roman Catholicism rests on the infallibility of the Pope, in Orthodoxy canonization of a saint rests on the Church being guided infallibly by the Holy Spirit. Where infallibility is a nature of the Holy Spirit, the infallibility of the Orthodox Church is by grace. I invite Orthodox priests reading this to give us their input.

Robert

Robert, I said this primarily because I remember reading that there are a few Saints on the church calendar who it appears quite likely from all the evidence we have that they never actually existed, and were added accidentally through human error. (I’m sorry I don’t remember where now.) I realize now that you have said the above, that this is not the same as claiming that a Saint, duly recognized by the Church in the normal process for which we actually have some evidence, may not actually be a Saint. I, too, would welcome input and correction by a Priest or scholar more knowledgable about this subject.

I’ve heard as much about St. Martin of Tours, but I’m not in a position to adjudicate veracity.

Russ

Russ, Compared to King Henry the 8th and other later kings, the Emperor Constantine was a Saint! One of the questions I ask others is:

“Did he force the pagan population of his kingdom to convert like the Frankish and Slavonic kings?”

I personally think that when we compare him with other Christian kings, then we will see that his short comings are pretty mild. I even feel that way when we compare him to most Old Testament kings, King David included. I mean, King David had to kill family members just like Saint Constantine did. And so when we compare him to other kings then we will see that his short comings aren’t really all that awe-full.

I know that alot of people look to the fact that he wasn’t Baptized till his death bed, but people tend to forget the whole background of Baptismal Regeneration and the popular idea back in those days that there were only so many times one could repent for serious sins after water Baptism.

Another issue I see people use is the semi-Arian or moderate Arian-bishop that Baptized him (The homoiousions), but what people don’t realize is that the moderate Arians were the same ones that eventually came back in communion with the Nicene party some decades later after they saw what Arianism could lead to by watching the evolution of the radical Arians. Saint Athanasius was the one who was able to bring them back after decades of infighting between the various parties. He knew that the homoiousions didn’t like the radicals and so when the time was right he was able to bring them back in communion.

from page 82 (in regards to the feud between the Old Nicene Party and the homoiousion moderate Arians)

“Quote:

“The aftermath

“The Church historian Socrates (380-450) describes the failure of mutual understanding: “The situation was like a battle by night, for both parties seemed to be in the dark about the grounds on which they were hurling abuse at each other. those who objected to the term homoousios imagined that its adherents were bringing in the doctrine of Sabellius and Montanists. So they called them blasphemers on the ground that they were undermining the personal subsistence of the Son of God. On the other hand, the protaganists of homoousios concluded that their opponents were introducing polytheism, and steered clear of them as importers of paganism……..Thus while both affirmed the personality and subsistence of the Son of God, and confessed tht there was one God in three hypostases, they were somehow incapable of reaching agreement, and for this reason could not bear to lay down arms.”

[ page 82 from the book “the first Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787): Their History and Theology” by Leo Donald Davis ]

How Saint Athanasius was able to heal the division(some many decades later):

from pages 102-103

quote:

“Athanasius’ main concern was to reconcile the moderates and the Nicenes by getting behind party catchwords to the deeper meaning of each position. He recommended asking those who held three hypostases if they meant three in the sense of three subsistent beings, alien in nature like gold, silver and brass, as did the radical Arians. If they answered no, he asked if they meant by three hypostasis a Trinity, truly existing with truly substantial Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and if they acknowledged one Godhead. If they said yes, he allowed them into communion. Then he turned to those who spoke of one hypostasis and asked if they meant this in the sense of Sabellius, as if the Son were not substantial and the Holy Spirit impersonal. If they said no, he asked them if they meant by one hypostasis one substance or ousia because the Son is of the substance of the Father. If their answer was yes, he accepted them into communion. Finally, in a statesmanlike fashion Athanasius brought out the truth each side was fighting for and showed that between the moderates and the Nicenes there was really no ground for disagreement.” [from pages 102-103 from the book the first Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787): Their History and Theology by Leo Donald Davis]

And so the moderate-Arians(in whom Saint Constantine was Baptized by) really weren’t all that bad. The radical Arians were the bad ones.

In regards to saints, I could be wrong, but I think we have different levels or different categories in regards to the Canonization of Saint hood. Like for instance I was told somewhere that the last Russian Czar and his family, were seen as low level saints. Now I could be wrong about that, but that’s what I heard.

This is called “Constantine the Great and Historical Truth” on an Orthodox website in Greece:

http://www.oodegr.com/english/paganismos/sykofanties/kwnstantinos_ist_alithia1.htm

Well, Constantine is closer to the neo-cons and fought a civil war for politcal power. Constantine like Justinian isn’t all villian but not all saint either.

Actually to many Evangelicals who are more pro-military Constantine is view more favorably now than in Mainline Churches that are more pacfists. The Lutheran Missouri Synod the most conseravtive of mainline churches honors Constantine. A lot of Mainline church pastors and leftwing Evanglelicals seen Constantine as changing the church from a pacifists view to a milalastic view adopting Roman Statism. Evangelicals don’t all see Constantine as the bad guy its mainly the religoius left that hates him for his wars and putting to death his wife and son for adultery. Constantine was too much of a social conservative.

You pointed out this review in responding to a comment I left on another thread. A very fair review. You might profit from reading the review at http://erb.kingdomnow.org/featured-a-yoderian-rejoinder-to-leitharts-defending-constantine-vol-3-46/

There is a response by Leithart linked there.

One further comment, and this is kind of inside baseball from an Anabaptist perspective, you state:”This stream of Protestantism holds that the church is a community of faithful believers who renounce all worldly power and adheres to pacifism. ” Yes, but…. Yoder marked an important break with classic Antibaptist thinking in that he advocated pacificism, but not passivism. Classic American Mennonites (Yoder’s denomination) would, for example, say the Church should patch up the wounds suffered by a Civil Rights demonstrator, whereas Yoder was an enthusiastic advocate of MLK’s marches, even though King knew they would provoke a violent response. Neo-Anabaptists like Yoder’s acolyte Huerwas take off from this distinction.

Finally, the historograhical issues that Leithart raises are pretty old hat. I attended a symposium over 25 years ago devoted to “The Politics of Jesus.” One of the presenters was a history prof at a secular University who essentially said Yoder had laid too much guilt on poor Old Constantine, but that pretty much everything Yoder complained of was true of later Byzantine rulers. In his response, Yoder thanked the guy, and moved on to engage the two theologians who were on the panel.

Thanks for pointing me to your review.