Tell me the history of the church and I can tell you your theology.

Church history is not neutral but is shaped by our theological beliefs. This is especially the case with Emperor Constantine:

- to many Evangelicals and Anabaptists Constantine was the arch villain who caused the early Church to fall from its apostolic purity,

- to mainstream Protestants and Roman Catholics Constantine was a pivotal historical figure who made Christianity into a public religion,

- to Eastern Orthodox Christians he is Saint Constantine “equal to the apostles.”

Defending Constantine by Peter J. Leithart is more than a biography of Constantine the Great. It starts off as a theological history and ends as an attempt to construct a political theology. Leithart draws upon a wide range of scholarship to present the reader with a fine grained and nuanced understanding of Constantine the man and the consequences of his embrace of Christianity.

Pastor Leithart’s underlying motive for writing this history is to refute John Howard Yoder‘s radical Anabaptist political theology. This stream of Protestantism holds that the church is a community of faithful believers who renounce all worldly power and adheres to pacifism. This position leads Yoder to the position that Constantine never truly converted to Christianity and that the Christian church he allied himself with was a fallen, compromised church (see Leithart pp. 252-254; 305-306). By refuting Yoder, Leithart intends to present Constantine as a model for Christian political practice.

The purpose of this review is not just to assess Leithart’s book but also to comment on some of his ideas from the standpoint of an Eastern Orthodox Christian.

Constantinian Paradigm

Constantine’s historical significance lies in his embrace of Christianity which laid the basis for the Constantinian paradigm. This is the belief that Christianity has a rightful place in the public sphere and that the church has an obligation to bring Christian moral values to the family, society, and politics. Similarly, the Constantinian paradigm views Christian clergy as public leaders and allows for the use of state resources to support the church. This alliance which began with the Edict of Milan in 313 would frame Western society and politics until the 1800s and 1900s. The Constantinian paradigm began to be displaced by the Enlightenment which gave rise to non-theistic systems of thought like Communism and Rawlsian liberalism.

Constantine matters to Reformed and Orthodox Christians because both traditions rely on the Constantinian paradigm. Important to Reformed theology is the belief that the call to reformation extends not only to the church but to society as well. This is apparent in the last chapter of Calvin’s Institutes “Civil Government” (Book 4, Chapter XX). While Reformed Christians might agree with Yoder on the fall of the church, they would disagree with his view of the church as a pure community of disciples removed from society.

Eastern Orthodox Christians will likewise take issue with Yoder’s political theology, especially with the assumption of the fall of the church. The Orthodox Church believes that it has maintained an unbroken chain of apostolic succession going back to the original apostles. Furthermore, Orthodoxy holds to the doctrine of symphonia — the doctrine of church and state distinct from each other but working in harmony.

Leithart does the Christian community a great service with his discussion of the historical origins of the notion of the fall of the church (p. 307). He shows how Yoder’s allegations that Constantine corrupted the church rests on poor history (p. 317-321). Leithart shows that Yoder’s flawed church history leads to a defective theology. His critique of Yoder’s historiography demonstrates the aphorism stated at the outset of this blog posting: Tell me the history of the church and I can tell you your theology.

Discipling the Nations

Constantine was not the first emperor to issue edicts of toleration. What distinguishes him was his turn away from Roman paganism and his supportive attitude towards Christianity. When Constantine defeated Maxentius and entered Rome as victor, rather than follow the conventions which stipulated that the victor enter the Capitolium and offer sacrifice to Jupiter, he refused (p. 66). This marked an epochal shift in Rome’s political culture. Constantine’s outlawing of the gladiatorial shows reshaped Roman culture. It in effect shut down a key means by which the populace were instructed in the values of violence and martial glory (Leithart p. 304).

In embracing the Christian cause Constantine did not relinquish the power of the sword. He continued to engage in military campaigns and he continued to engage in political intrigues characteristic of any political elite. His refusal to abandon the powers of the state is a disappointment to those who hold an Anabaptist political theology.

Another momentous decision by Constantine was the founding of Constantinople, the New Rome (pp. 119-120). This decision was rooted in Constantine’s desire to raise up a new metropolis built from a Christian foundation. The old Rome, the traditional center of power, was deeply stained by its pagan past. From the standpoint of political theology the establishment of Constantinople reflected the belief in the possibility of a Christian civilization. This can be traced to the call to disciple the nations in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19-20) and in the eschatological vision of the New Jerusalem in Revelation. The radical Anabaptist tradition disavows the possibility of the Christianization of societies and holds instead to the idea of a Christian counter culture marked by ethical purity and pacifism.

There is a certain paradoxical quality to the attitudes that Eastern and Western churches hold towards Constantine. In the Western tradition Constantine is more of a remote historical figure, yet there has been considerably more discussion about the Constantinian paradigm, i.e., how politics ought to be shaped by Christian values. Thus, Leithart’s book is part of a long running debate in the Western tradition. Eastern Orthodoxy venerates Constantine as a saint, but there is relatively little written about political theology in the Eastern tradition.

Constructing a Political Theology

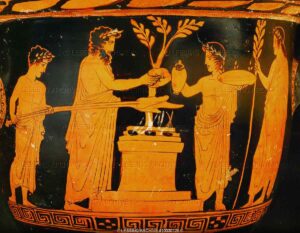

One of the fascinating insights presented by Leithart is his argument that: (1) every ancient city had a sacrificial center, (2) Constantine’s significance lies in his abandonment of the responsibility of attending to the sacrifices expected of Roman emperors, and (3) just as significant his welcoming the church, the city of God founded on the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross (pp. 326-331). Leithart’s political theology juxtaposes pagan Rome against the New Jerusalem, the Church.

He writes:

The church too was a sacrificial city, the true city of sacrifice, the city of final sacrifice, which in its Eucharistic liturgy of sacrifice announced the end of animal sacrifice and the initiation of a new sacrificial order (p. 329).

I found chapter 6 “End of Sacrifice” especially helpful for understanding the way religion and sacrifice permeated pagan Rome and how Constantine’s “conversion” led to the passing of pagan sacrificial system and the ascendancy of the Christian Eucharist as the basis for Western culture. What is striking about this passage is that one can easily see in Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy a resemblance to the sacrificial city described by Leithart, but it is much harder to see this resemblance in the Reformed churches due to the fact that the sermon has displaced the Eucharist in many Reformed congregations. Nonetheless, it should be noted that many Reformed churches still proclaim Christ’s sacrificial death.

As an Orthodox Christian I would like to point out the role of the early martyrs in the evangelization of the Roman Empire. The ancient polis rested on the civic liturgy, i.e., public officials offering up sacrifices to the gods to ensure the well being of the city. The ancient Christians attacked the ancient sacrificial system through two means: (1) the proclamation of the Good News of Christ’s death and resurrection, and (2) their willingness to sacrifice their lives for the Gospel of Christ. The inability of the authorities to cow the Christians like Polycarp into offering up the traditional sacrifices meant the end of the pagan religions.

Leithart asserts that Constantine provides a model for Christian political practice. As much as I’d like to support Leithart in this there are a number of questions that need to be raised from an Eastern Orthodox perspective. One is that Constantine was a catechumen for much of his adult life and was not baptized until shortly before his death. The significance here is that he was able to rule with a relatively free hand executing members of his household without fear of excommunication. The first Christian emperor was Theodosius who was baptized shortly after he became emperor. It was only because Theodosius had been baptized that Bishop Ambrose of Milan was able to threaten him with excommunication over the massacre of 7000 in Thessalonica in 380. The sacrament of baptism effectively brought the most powerful man in the Roman Empire under the authority of the Church. It would have been good for Leithart to have qualified his touting Constantine as a role model for Christian politics by presenting him as providing the beginning of a social template and by including other notable Christian rulers, e.g., Justinian the Great in the East and Charlemagne in the West.

Post-Constantinian Society

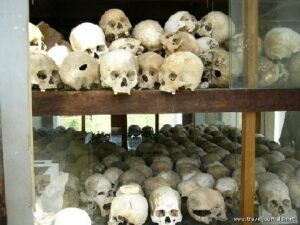

In the subsection “There Will Be Blood, Again” (pp. 340-341), Leithart discusses the implications of a post-Constantinian society. He asserts that when the modern state excludes the church, it has no moral brakes to speak of and instead seeks to be “resacralized” by other means (p. 340). This is a point that needs to be explored through a discussion as to whether or not the Nazi Holocaust, Mao’s Great Leap Forward, Pol Pot’s killing fields, and the so-called “right” to abortion are modern equivalents to ancient ritual offerings to the gods. Leithart’s suggestion of a grim nihilistic future politics is something that Christians need to take seriously. “There Will Be Blood” is a fascinating discussion of modern politics and if I have a criticism it is that it is far too brief. Only two pages?!

Conclusions and Findings

In this reviewer’s opinion Leithart’s critique of Yoder’s Anabaptist political theology is like fighting yesterday’s war. He touches on modern politics in just the last few pages of the book (pp. 340-341). Hopefully, Leithart will be writing more on this important subject matter.

Any attempt to construct a Christian political theology needs to study Constantine’s impact on the church’s role in society. Without question, it is Constantine who made Christianity into a public religion. Much of American political history, e.g., the Moral Majority, the Prohibition, the Abolitionist movement, the Puritan Commonwealth all assume the Constantinian paradigm. The widespread influence of anti-Constantinianism has impeded the ability of Christians to scrutinize Christianity’s role in modern society. It has also prevented many Christian leaders from understanding the significance of the recent move away from the Constantinian paradigm in America.

Reading Defending Constantine has made me conscious of a significant difference between Western and Eastern Christianity. Where the West has had a long continuous history with the Constantinian paradigm, Eastern Christianity has suffered numerous disruptions, e.g., the Muslim conquests of North Africa, the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 and the Bolshevik Revolution in 1918. However, with the Greek War for Independence in the 1820s and the fall of Communism in the late 1980s we see attempts being made to bring back some form of the Constantinian paradigm in Russia and in the Balkans with results that can be disconcerting for Westerners schooled in Lockean liberalism. My impression is that American Protestants and Roman Catholics are much more comfortable speaking up in the public square and theorizing on Christians’ role in politics than the Orthodox. This can be seen in Liberation Theology in Roman Catholic circles and Christian Reconstructionism in Protestant circles. Orthodoxy in America has been much more reticent in its public witness despite its doctrine of symphonia. It has yet to match the literary output of Christian political thinkers in the West. There is much Christians from both the Reformed and Orthodox traditions can learn from Constantine. Leithart has done us a great favor by critiquing the anti-Constantinian prejudice widespread in American Protestantism and his presenting Constantine as a model for political theology.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments