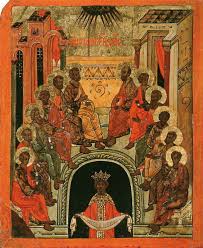

For me, the icon of Pentecost is one of the more intriguing and puzzling icons.

For me, the icon of Pentecost is one of the more intriguing and puzzling icons.

Unlike the lively emotionalism and expressiveness of Pentecostal worship, in this icon “nothing” seems to be happening. But as I gaze at this icon, I gain insight into the Church’s understanding of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost. I used to be part of the charismatic renewal, so when I began to look into Orthodoxy I was surprised by the sobriety and the stillness of Orthodox spirituality.

The Spirit Descending

The Pentecost icon can be broken down into three sections. At the top we see a half circle with rays emanating outward. This represents the Holy Spirit descending from heaven. This abstract depiction probably reflects a certain conservative streak in Slavic Orthodoxy that frowns on using a dove to represent the Holy Spirit. Nowhere does Scripture teach that the Holy Spirit came down on Pentecost in the form of a dove.

The circle can be understood to represent the one divine Essence of the Holy Spirit and the rays extending outward as the uncreated energies filling the universe. This simplicity with diversity is supported by Scripture like Luke’s narration of the Day of Pentecost in which the one Spirit is manifested in a multitude of flames.

Then there appeared to them divided tongues, as of fire, and one sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance. (Acts 2:2-4)

It is also supported by John’s Revelation.

Then I turned to see the voice that spoke with me. And having turned I saw seven golden lampstands, and in the midst of the seven lampstands one like the Son of Man . . . . (Revelation 1:12-13)

Seven lamps of fire were burning before the throne, which are the seven Spirits of God. (Revelation 4:5)

In Revelation’s rich visual language we see references to the Trinity. Jesus stands before the throne of God the Father, and he stands in the midst of the seven lampstands which symbolize the Holy Spirit. The number seven represents fullness and perfection. It can also represent complementarity and diversity; Paul wrote in I Corinthians 12:6: “And there are diversities of activities, but it is the same God who works all in all.”

The Apostles Sitting

In the middle of the Pentecost icon we see the twelve Apostles sitting in a half circle in perfect harmony. This reflects the historic Day of Pentecost.

When the Day of Pentecost had fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. (Acts 2:1)

One important means of understanding an icon is to look at the posture taken by the main characters. The Apostles sitting indicate their occupying a position of authority (Revelation 4:4).

The twelve Apostles sitting in a half circle bears a resemblance to Rublev’s Holy Trinity icon where the three angelic visitors sit in a half circle around the dinner table in perfect fellowship. This points to eternal life and to Pentecost’s connection to our deification in Christ.

The icon presents Pentecost, not so much as a historical event, but a spiritual reality that transcends history. Pentecost was not a onetime event but is an ongoing reality flowing into human history. As we reflect on the icon prayerfully we participate in the reality depicted by the Pentecost icon.

Divine grace was manifested in the God-Man Jesus Christ, but at Pentecost divine grace is manifested in the Church, the Body of Christ. The Church is not a mere human organization, but a sacrament for the world.

The World Waiting

At the bottom of the Pentecost icon we see a lonely figure named “Cosmos.” This depicts the natural universe in its fallen state, in darkness, in isolation. “Cosmos” is clothed in royal attire and has a crown on his head. This teaches the dignity which God bestowed on creation at the beginning. “Cosmos” holds a cloth with twelve scrolls representing the teachings of the Apostles. This teaches the Great Commission, that is, Christ sending his Apostles to disciple the nations (Matthew 28:19-20).

At the bottom of the Pentecost icon we see a lonely figure named “Cosmos.” This depicts the natural universe in its fallen state, in darkness, in isolation. “Cosmos” is clothed in royal attire and has a crown on his head. This teaches the dignity which God bestowed on creation at the beginning. “Cosmos” holds a cloth with twelve scrolls representing the teachings of the Apostles. This teaches the Great Commission, that is, Christ sending his Apostles to disciple the nations (Matthew 28:19-20).

The evangelization of the nations will lead in time to redemption of the entirety of the cosmos. The Fall was a cosmic catastrophe. The natural environment suffer the consequences of Adam and Eve’s rebellion against their Creator. By the Incarnation, the Creator God entered into the cosmos acquiring materiality. By his dying on the Cross Christ engaged the realities of sin and death, and by his Resurrection Christ defeated sin and death opening the way for the restoration of all things (Acts 3:21). This is the basis for the Christian hope. Paul wrote:

For the earnest expectation of the creation eagerly waits for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of Him who subjected it in hope; because the creation itself will be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God. (Romans 8:19-21)

For we know that the whole creation groans and labors with birth pangs together until now. Not only that, but we also who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, eagerly waiting for the adoption, the redemption of our body. For we were saved in this hope, but hope that is seen is not hope; for why does one still hope for what he sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, we eagerly wait for it with perseverance. (Romans 8:22-25)

I would suggest that what unites both the Apostles and “Cosmos” is the theme of waiting. Both the redeemed and those in darkness are yearning for redemption from death, sin, and futility. Having heard the Good News, Christians have hope in the future resurrection, while those who have not yet heard the Good News of Christ are longing for something they know nothing of. This inchoate yearning becomes an eager hope through faith in Christ. It is for the Church to send out missionaries to proclaim the Good News into the spiritual darkness and confusion of our times.

Read from top to bottom, the Pentecost icon can be understood as Christ bestowing his Spirit on his Church. It also teaches us about the Church’s mission to the world. Returning to the middle it teaches us that our calling is eternal life in the Trinity and fellowship with one another.

Incarnation and Pentecost and the Trinity

In closing, Pentecost flows logically from the Incarnation. Both are necessary for our salvation. In the Incarnation the Son of God took from us human nature, and in Pentecost the Son of God gave to us his Spirit, the Third Person of the Trinity. Jesus Christ went away on Ascension Thursday in order to prepare the way for Pentecost Sunday. As Christians we become drinkers of the Spirit of God (John 4:10) and through faith in Christ we become part of the river of God. Jesus promised:

If anyone thirsts, let him come to Me and drink. He who believes in Me, as the Scripture has said, out of his heart will flow rivers of living water. (John 7:37-38)

The icon of Pentecost is ultimately about our life in Christ and about our being joined to the Trinity. Jesus prayed: “I in them, and You in Me; that they may be made perfect in one, and that the world may know that You have sent Me, and loved them as You have loved Me.” (John 17:23) Let us be inspired by the Pentecost icon to live a life of unity and harmony with one another and with the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Recent Comments