Icon – St. Patrick

This coming Sunday will mark the feast day of Saint Patrick – Bishop of Armagh and Enlightener of Ireland. This may come as a surprise to many that St. Patrick was and is an Orthodox Saint centuries before Rome split from the Holy Apostolic Church.

The rule of thumb for Orthodox Christians is that a Latin Christian who lived after the Great Schism of 1054, while they may have lived exemplary lives, are not saints in the full sense of the Church’s understanding. But because he lived from c. 385 to 17 March 460/461 Patrick is considered part of the undivided Church and therefore is an Orthodox saint.

St. Patrick’s Life

The name “Patrick” is derived from the Latin “Patricius” which means “highborn.” He was born in the village of Bannavem Taburniae. Its location is uncertain; some scholars place it on the west coast of England, while others place it in Scotland. His father was Calpurnius, a Roman Decurion (an official responsible for collecting taxes) and a deacon in the church. His grandfather, Potitus, was a priest.

This means that Patrick had a solid Christian upbringing and was well acquainted with the refinements of Roman civilization. But he lived on the edge of civilization at a time when the Roman Empire was under siege by barbarians. When Patrick was sixteen he was kidnapped by pirates, taken to Ireland, and there sold as a slave. He was put to work as a herder of swine on a mountain in County Antrim.

Looking back on his youth, he recounts:

I was at that time about sixteen years of age. I did not, indeed, know the true God; and I was taken into captivity in Ireland with many thousands of people, according to our deserts, for quite drawn away from God, we did not keep his precepts, nor were we obedient to our priests who used to remind us of our salvation. (Confessio §1)

Although Patrick had a Christian upbringing, he took his faith for granted. This complacency would be shaken by the calamity of being taken into exile. For the next six years he spent much of his time in solitude and prayer which would prepare him for life as a monastic. During this time Patrick also learned the local language which would prepare him for his future work as a missionary bishop.

But after I reached Ireland I used to pasture the flock each day and I used to pray many times a day. More and more did the love of God, and my fear of him and faith increase, and my spirit was moved so that in a day [I said] from one up to a hundred prayers, and in the night a like number. . . . (Confessio §16)

His escape from slavery resulted from two visions. In the first vision it was revealed that he would return home. The second vision told him his ship was ready. He then walked two hundred miles to the coast, succeeded in boarding a ship, and reunited with his parents.

Sometime later Patrick studied for the priesthood under St. Germanus in Gaul (France). Eventually, he was consecrated as a bishop and entrusted with the mission to Ireland. Patrick had a dream in which he heard the Irish people begging him to come back to them. There were other missionaries in Ireland but it was St. Patrick who had the greatest success. For this reason, he is known as “The Enlightener of Ireland.”

Evangelizing the Irish people was not an easy task. The Irish populace regarded him with hostility and disdain. He was a foreigner and, worst yet, a former slave. Despite the opposition, Patrick persevered in his missionary calling and baptized many into Christ. This resulted in churches and monasteries all across Ireland.

In his autobiography Patrick described his motivation for doing missionary work:

I am greatly God’s debtor, because he granted me so much grace, that through me many people would be reborn in God, and soon after confirmed, and that clergy would be ordained everywhere for them, the masses lately come to belief, whom the Lord drew from the ends of the earth, just as he once promised through his prophets: ‘To you shall the nations come from the ends of the earth. . . . (Confessio §38)

St. Patrick’s missionary labors would result in a blessing, not just to the Irish, but to humankind as well. How the Irish Saved Civilization by Thomas Cahill tells how Ireland became an isle of saints and scholars, preserving Western civilization while the Continent was being overrun by barbarians.

American culture has been richly blessed by the presence of the Irish. In the US, March 17th has become something close to a national holiday. While in many instances St. Patrick’s day has become more of an excuse for partying, it can also be made into an occasion for renewing our faith in Christ.

St. Patrick’s Faith

We learn of his faith through the well known Breastplate of St. Patrick. It is also known as the Lorica (Latin for ‘breastplate.’). In the monastic tradition a lorica is a prayer/incantation for spiritual protection.

Below are some excerpts of the rather lengthy but powerful and inspiring prayer. There is a strong masculine and militant tone in Patrick’s prayer that contrasts with the softer, more feminine quality of later Christian spirituality.

I arise today

through a mighty strength,

the invocation of the Trinity,

through belief in the Threeness,

through confession of the Oneness of the Creator of creation.

I arise today

through the strength of Christ with His Baptism,

through the strength of His Crucifixion with His Burial,

through the strength of His Resurrection with His Ascension,

through the strength of His descent for the Judgment of Doom.

Patrick’s commitment to Orthodoxy can be seen in the third stanza which refers to the fellowship of the saints and angelic hosts. His was not the faith of rugged individualism but one marked by a profound awareness of the interconnectedness with the spirit and biblical worlds as expressed in the Liturgy.

I arise today

through the strength of the love of Cherubim,

in obedience of Angels, in the service of the Archangels,

in hope of resurrection to meet with reward,

in prayers of Patriarchs, in predictions of Prophets,

in preachings of Apostles, in faiths of Confessors,

in innocence of Holy Virgins, in deeds of righteous men.

In the fourth stanza we learn of Patrick’s zeal for holy Orthodoxy and spiritual warfare against the forces of darkness.

I summon today all these powers between me (and these evils):

against every cruel and merciless power that may oppose my body and my soul,

against incantations of false prophets,

against black laws of heathenry,

against false laws of heretics,

against craft of idolatry,

against spells of witches and smiths and wizards,

against every knowledge that endangers man’s body and soul.

Christ to protect me today

against poison, against burning,

against drowning, against wounding,

so that there may come abundance of reward.

Living in dangerous times Patrick was keenly aware of the dangers all around him and constantly invoked divine protection as he went about his missionary and pastoral labors.

As amazing as it may be to Orthodox Christians, I was informed that a Reformed church of the CREC denomination, who in their new-found interest in Liturgy and broad catholicity, have made it their practice to sing St. Patrick’s Lorica in its entirety at every Baptism before worship!

Honoring St. Patrick Today

One key means by which the Orthodox Church honors its saints is by remembering them on their feast day. Usually during the Vespers and Matins service preceding the Liturgy, we hear a short summary of the saint’s life and sing a hymn celebrating God’s work in that saint’s life. The Orthodox Church in America’s website posted the two hymns for St. Patrick’s feast day:

Troparion — Tone 3

Holy Bishop Patrick, / Faithful shepherd of Christ’s royal flock, / You filled Ireland with the radiance of the Gospel: / The mighty strength of the Trinity! / Now that you stand before the Savior, / Pray that He may preserve us in faith and love!

Kontakion — Tone 4

From slavery you escaped to freedom in Christ’s service: / He sent you to deliver Ireland from the devil’s bondage. / You planted the Word of the Gospel in pagan hearts. / In your journeys and hardships you rivaled the Apostle Paul! / Having received the reward for your labors in heaven, / Never cease to pray for the flock you have gathered on earth, / Holy bishop Patrick!

Our Lady of Walsingham Orthodox Christian Church (Antiochian) in Mesquite, Texas, near Dallas, will be celebrating St. Patrick’s feast day not just liturgically but by serving corned beef and cabbage afterwards.

Another way the Orthodox Church honors its saints is by naming a church after them. There is for example St. Patrick Orthodox Mission (ROCOR) in Wayville SA, near Adelaide, Australia. By taking on the name of a particular saint it seeks to imitate that saint and seeks the prayers of that saint. The mission’s goal is to provide a spiritual home for Orthodox Christians who do not currently attend a church, as well those who desire an English service. This parish also seeks to help non-Orthodox discover the richness of the Orthodox Faith.

Where is St. Patrick in the Orthodox Church Today?

A friend of mine in a recent email asked why his local Greek parish did not celebrate St. Patrick’s feast day. He wrote:

HOWEVER . . . . there IS a difference between Americans attending an Orthodox church and infecting that parish with their cultural personality, versus an American Orthodox Church as an institution headed by American bishops. We have somewhat “Americanized” the Orthodox Church here, but not to the extent that we have supplanted the ethnic identity of the parish’s Motherland. I still hear plenty of Greek spoken in the social hall after service, let alone being exposed to Greek dance practice, Greek posters on the walls, and Greek cuisine.

Let’s put it this way: this Sunday will be St. Patrick’s Day. He IS an Orthodox Saint! However, will there be ANY mention of him at church by the priest? Will the choir or chanter sing his hymns? Will his icon be placed in the narthex? Yes, St. Paddy was Irish, but he has become incorporated into the American ethos such that every calendar printed in this country notes the holiday, and every city in this nation has a celebration of him. Yet, will our church acknowledge one of their own? No, because he is a Western saint, and GOA only recognizes the Eastern Roman Empire’s contribution to Orthodoxy. And as long as it does so. . . wait for it. . .there will never by an American Orthodox Church!

My friend made some good points. St. Patrick is honored by some Orthodox jurisdictions, like the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR), but neglected by others like the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese in America (GOA). This observation applies not just to St. Patrick but to other Orthodox saints as well. For example, St. Herman of Alaska, St. Peter the Aleut, St. Innocent, St. Juvenaly are all American Orthodox saints. These Orthodox Christians played a key role in bringing Orthodox Christianity to America but I have yet to hear them honored in the services of the Greek Orthodox church I attend. I often wonder about this oversight and am almost persuaded it is shameful.

I think my friend’s uncomfortable observations about Orthodoxy in America shines a spotlight on some areas where we can mature as a faith community. It seems that some jurisdictions see themselves more as belonging to the old world than to America where they now live. While some are recent immigrants, the vast majority of Orthodox Christians in the US were born and raised in America.

Neglecting to honor western saints like St. Patrick is a far from a minor issue. It impacts our ecclesiology. The Orthodox Church is the one holy catholic and apostolic Church confessed in the Nicene Creed. I use the phrase “Eastern Orthodoxy” sparingly because I do not want to give the impression that Orthodoxy is for the East and Roman Catholicism is for the West. With the tragedy of the Great Schism it has become the responsibility of the Orthodox Church to embrace, preserve, and carry on the rich spiritual legacy of Western Christianity. The Orthodox Christian Church is not another denomination, but the Church catholic encompassing all the Earth – East and West, North and South. Orthodoxy in America needs to be rooted in American society and culture rather than be a colonizing presence for the old world. If all Orthodox jurisdictions in the US were to celebrate St. Patrick’s feast day we will have taken a major step towards an American Orthodox Church.

Lessons From the Life of St. Patrick

One, Patrick was blessed with being born into a family of committed believers but had drifted away from God. He saw his captivity as punishment for his earlier sins but also as an opportunity to return back to God. Similarly, we need to remember to be vigilant in our spiritual life but also to be mindful that God can use hardships as a means of spiritual growth.

Two, life is often more fragile than we know. Patrick lived on the edge of Roman civilization where life was often far from stable or secure. He was among the thousands who were taken captive by the barbarians. For those of us who feel like the world as we know it is on the verge of collapse, we need to remember God rules over human history even while this sovereignty seems hidden from our eyes.

Patrick lived in a time when the Roman world was under siege by barbarian forces and at a time when a new Christian society was emerging. In 410 Rome was sacked by Alaric and soon after that the western half of the Roman Empire slid into the dark ages. But thanks to Emperor Constantine’s foresight the Roman Empire continued in the New Rome of Constantinople which was founded in 330. Roman civilization would endure another thousand years in the East until the Ottoman conquest in 1453.

Three, God worked through the tragedies in Patrick’s life. Patrick’s abduction took him away from his Christian surroundings into an unreached people group. His time as a slave gave him a knowledge of Irish culture and language that would later enable him to preach Christ. The practical skills acquired now can be used for God’s kingdom in the future.

Four, trials and hardship can become a means of spiritual growth. The lonely work as a goatherd prepared Patrick for the monastic life of solitude and prayer. In our life are hidden opportunities for prayer and meditation waiting to be discovered.

Five, the earlier hardships gave Patrick an inner toughness and steadfastness that would enable him to preach Christ in the face of fierce opposition. Rather than complain about our current hardships we can allow them to teach us the inner strength to persevere and prepare us for some future task ordained by God.

Six, Patrick’s life and mission teach us the importance of the Great Commission to Orthodox Christianity. The Christian faith is broad and catholic, it is meant for all peoples, not just for particular ethnic groups.

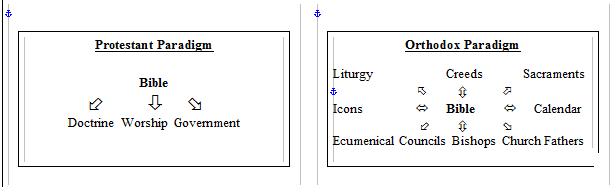

Finally, I would be remiss not to notice the challenge Saint Patrick presents to our Protestant friends who are so interested in the early church fathers and the lives of the pre-schism saints. This interest is also based on the fact that these saints did not embrace Rome’s later innovations like forbidding priests to marry, Mary’s immaculate conception or her being co-redemptrix for our salvation, papal supremacy over all bishops, and papal infallibility. St. Patrick (385-460/461) lived around the time of other great saints like Ambrose of Milan (c. 339-397), Augustine (354-4300, Basil the Great (c. 329-3790, Athanasius (329-373), Jerome (c. 345-c. 419), Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 310- c. 386). Saint Patrick embraced the Orthodoxy of his day, e.g., the Liturgy, the office of the bishop, the first and second Ecumenical Councils, the Nicene Creed without the Filioque, the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and monasticism. It is commendable that Protestants are using St. Patrick to rediscover their historic roots, but one should stop to ponder whether it is wise to pick and choose their heroes of the faith. Are they doing it because it is the cool thing to do today or because it is part of Holy Tradition? Wouldn’t it be better to embrace the Holy Tradition taught and proclaimed by St. Patrick? And wouldn’t it be wiser to embrace the entire communion of saints recognized by historic Orthodoxy? Wishing you all a blessed St. Patrick’s Day!

Robert Arakaki

On 31 March 2013 Western Christians (Protestants and Roman Catholics) will be celebrating Jesus Christ’s rising from the dead.

On 31 March 2013 Western Christians (Protestants and Roman Catholics) will be celebrating Jesus Christ’s rising from the dead.

Recent Comments