Dear Folks, Burckhardtfan wrote some important questions about Ignatius of Antioch’s understanding of the early Church. As my answer grew longer I decided to turn it into a blog posting.Burkhardtfan wrote:

Mr. Arakaki,

Thank you for another brilliant post. I just have two questions:

1. When Ignatius says that nothing should be done without the bishop, what does he mean by the word ‘bishop’? Does it mean a local pastor or someone with authority over local congregations in a certain area? Congregationalists believe that local churches should be completely autonomous, believing that any external authority which in any way dictates the affairs of a local church is illegitimate. This is especially prominent among Baptist churches; they jealously guard their independence. Does Ignatius or any other father clarify what they mean by a bishop or describe the functions of this particular office?

2. In the same passage, what is the phrase ‘catholic church’ in the original Greek/Latin (I don’t know which language Ignatius wrote in)? Does it really mean ‘universal’ in the original Greek/Latin, or is the English translation an interpolation? I know the Greek word ‘katholikos’ means universal; if this word is present, then I know the concept of a ‘catholic’ church existed from the very beginning (some Baptists completely reject the notion of a ‘universal Church’ – and some go so far as to reject the idea that the Church is the Body or Bride of Christ!)

God bless!

MY RESPONSE

1. The Office of the Bishop

In Titus 1:5 Paul reminds Titus that he gave Titus the assignment of appointing elders in every town and to “set in order the things that are lacking.” Here Titus is acting in the capacity of a bishop, and the elders playing the role of priests assigned to a local parish. It appears that there were already Christian fellowships in these towns but that they needed to be recognized and brought into proper relationship with the Church catholic. Also interesting is Titus 2:15: “These, then, are the things you should teach. Encourage and rebuke with all authority. Do not let anyone despise you.” This makes sense if Titus is acting as a bishop attempting to bring order to a troubled diocese. Given the egalitarianism of Baptist polity I cannot imagine a Baptist pastor exercising “all authority.” More significant is the Greek word επιταγης (epitage) which Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament vol. viii p. 37 has this to say: “…it denotes especially the direction of those in high office who have something to say.” (emphasis added) That the meaning of the original Greek “epitage” is based on authority coming from a higher office is consistent with the office of the bishop as a hierarchical position.

Acts 14:23 indicates that only qualified men were appointed (ordained) to office of elders. The verse also notes that this was the standard practice for local leaders to be appointed by those with apostolic authority. This was not an independent action by an autonomous congregation but a church under the authority of the Apostles. Baptist churches are self-organized, not by an external authority; this is contrary to Acts 14:23.

The following chapter (Acts 15) shows how the early Church responded to a theological crisis. In response to the controversy over whether Gentiles needed to become Jews in order to become Christians a council was convened in Jerusalem. This set a precedent for future Ecumenical Councils. (For those unfamiliar with church history, the Seven Ecumenical Councils defined the parameters of orthodox Christology and Trinity.) From the Jerusalem Council came a letter showing how the issue was resolved. This decision had binding authority on the churches. This is quite different from the Baptist polity.

Another indication of the bishop as the leader of the city can be found in Revelation 2 and 3 in which a letter was sent to the respective “angel” (bishop) of the cities of Asia. In Revelation 2:5 Jesus warns the bishop of Ephesus that he would be removed from office (remove your lampstand from its place) if he did not amend his ways. So when we look at Ignatius’ letters we see them addressed to the church of a particular city. This points to the local church as the unified gathering of congregations in one particular city or area. Ignatius could have addressed it to a particular home fellowship but he did not.

The word “bishop” is derived from the Greek επισκοπος (episcopos). It comes from “epi” (over) and “skopeo” (to pay attention to, be concerned about). The modern English word “supervise” is similar in meaning coming from “super” (over) and “vise” (to see) thus to “oversee.” Some denominations have superintendents instead of bishops but the overall function is similar. One critical difference is that Protestant superintendents cannot claim apostolic authorization for their office. See my posting on the office of the bishop and apostolic succession.

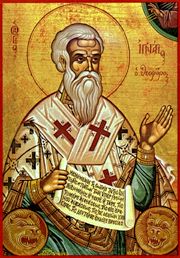

Ignatius of Antioch (d. 98/117) was very familiar with the polity of the early Church. He came from Antioch the home church of the Apostle Paul. According to the book of Acts Antioch was where Paul received his missionary calling and it served as his home base for his missionary journeys (Acts 13 and 14). Ignatius was the third bishop of Antioch after the Apostle Peter and Euodius, whom he succeeded in AD 68. Thus, Ignatius’ letters cannot be ignored as a later development but must be treated as a direct witness to the early church.

2. The Church Catholic

Regarding the Greek word καθολου (katholou) that Ignatius used in his letters, the Liddell-Scott Lexicon gives the following meanings: (1) on the whole, (2) in general, and (3) in the negative – not at all. Etymologically, “katholou” comes from “kata” (according) and “holou” (whole, all) and thus can mean: according to the whole. An excellent discussion of the emergence of the idea of the church catholic can be found in JND Kelly’s Early Christian Doctrines (p. 190):

If the Church is one, it is so in virtue of the divine life pulsing through it. Called into existence by God, it is no more a mere man-made agglomerate than was God’s ancient people Israel. It is in fact the body of Christ, forming a spiritual unity with Him as close as is His unity with the Father, so that Christians can be called his members.

So to answer your question is: No. The word “catholic” is not the same as “universal.” The word “universal” has more of the sense of geographic dispersion, being everywhere. The better word for that is the Greek word οικουμενη (oikoumene).

Let me give you an analogy to illustrate the notion of “according to the whole.”

Imagine a US embassy located in a far off country in Africa or Asia. That embassy is not the United States but it is definitely a part of the USA. An action taken there is applicable elsewhere in the US and American embassies around the world. This is because that embassy and its staff work under the authority of the US government.

In a similar manner, the Orthodox Church through apostolic succession exercises authority from Christ and his Apostles. What unites the local parish to the entire Church is the Eucharist in which we feed on the body and blood of Christ. The Orthodox parishes around the world shares in the same worship and doctrine. What one sees at one parish will be the same as other parishes around the globe. This liturgical and doctrinal unity is proof that Orthodoxy is the Church Catholic.

Imagine also a group of natives in the area who love the United States and want to be US citizens. They form an American club, read the US Constitution every week, eat hamburgers often, and celebrate the Fourth of July once a year. Would that make them US citizens? Of course not. They could pass for Americans but the key thing is whether they have the right to vote. This is the quandary of Protestants; they think that just holding a copy of the Bible in their hands make them a church. Early Christians like Ignatius of Antioch would strongly disagree. The key here is the Eucharist under the bishop. Ignatius wrote:

Let no one do any of the things appertaining to the Church without the bishop. Let that be considered a valid Eucharist which is celebrated by the bishop, or by one whom he appoints (To the Smyrneans VIII)

A Protestant might object: “What’s the big deal about the Eucharist? It’s just a symbol.” The answer to that is that historically Christians have always since the beginning affirmed the real presence in the Eucharist. The symbolic understanding is something that surfaced on the radical fringes of the Protestant Reformation. Because the Eucharist links the local church to the Christ’s death on the Cross, the Eucharist is the source of the Church’s covenantal authority. Thus, the way Baptists and Congregationalists celebrate the Lord’s Supper makes visible their disconnect from the early Church.

A Reminiscence

I used to belong to a congregational church. Once I was on the church by-laws committee. The moderator wanted to do some minor updating to the by-laws. I persuaded the rest of the committee to put everything up for review including the church’s statement of faith! I recommended some changes to the statement of faith that were approved. And ironically, the by-laws revisions led to my old church moving away from pure congregational polity to an elder model. As a congregational church we were free to do as we pleased. As an Orthodox Christian I look back on all this with amazement, amusement, and horror.

Kalihi Union Church – Photo by Joel Abroad

I understand and appreciate congregationalism’s emphasis on local church autonomy. It’s a very useful defense against a denomination attempting to impose strange doctrines on the local church. My former home church (Kalihi Union Church) was staunchly evangelical in the liberal mainline United Church of Christ. Over time I became concerned by the fact that that local church autonomy, while it provided some protection against liberal theology also made for a highly dysfunctional ecclesiology. Unity becomes more a mirage than a reality.

When I became Orthodox I found a sense of relief when I learned that the Orthodox bishops are constrained by Holy Tradition and that the entire Orthodox Church, including the laity, have a responsibility for guarding Holy Tradition. Just as reassuring was the fact that the Orthodox Church has kept the Faith without change for the past two thousand years.

Closing Question for Baptists and Congregationalists

The question I have for any Baptist or Congregationalist reading Ignatius of Antioch’s letters is: If the polity and worship practice described by Ignatius is at odds with your congregational polity and practice, whose church more closely resembles the early Church founded by the Apostles? Ignatius of Antioch’s which lives under the bishop and celebrates the Eucharist every Sunday or the Baptist/Congregational church which has no bishop and celebrates the Eucharist infrequently?

Robert Arakaki

This is again a brilliant piece of theological teaching concerning Church organization, very well supported by mostly direct biblical arguments, their Spirit being proven to be the same One who gave life to the whole of the Holy Tradition of the Orthodox Church, and written for everyone to understand. Thank you Robert!

yes very excellent! thank you again!

If you read Acts 15 closely, you will notice that the coincil implicitly condemns the notions of sola scriptura and “soul liberty” (i.e. no one has the right to impose their interpretations of the Bible on others). The council says it gave the Judaisers no authorisation to teach their doctrine (v. 25: “to whom we gave no such commandment). But if early Christians believed in sola scriptura, why didn’t the council appeal to their correct interpretation of the Bible (the OT) to shut up the Judaisers? Or at least appeal to a direct inspiration from the Holy Spirit? What does ecclesial authority have to do with shaping doctrine if your only authority is the Bible?

Verse 25 should then read: “Who do not understand the Scriptures as we do” or “Who did not receive the same Spirit of revelation as we did.” But it does not. And this was not the authority of a local pastor safeguarding doctrine at his church; the Judaisers were in every city. Here we see that the Apostles assumed the right to control doctrine in EVERY city in the world; the autonomy of local parished obviously meant nothing to them. And neither did the notion of soul liberty. In the early church, you could either believe the doctrine of the Apostles as sanctioned by their authority, or you could ‘choose’ to believe something else – literally, a ‘chooser’ or ‘heretic.’ The early church knew nothing of the idea of ‘just your conscience and the Bible.’ Paul called the Judaisers ‘vile dogs’ because they cicumvented the legitimate authority of the Apostles.

Congregational Protestants are in big trouble!

Burckhardtfan,

The ancient faith is getting it’s teeth into you 🙂

In your journey and zeal, be careful to love. When the light comes on for us it should reveal more darkness in us than in those around us. As you press wine out of the grapes of the scriptures, the Councils, the father’s, and the services of the church, let Christ make your heart merry but always soberly restrained with “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.” I too think evangelicalism will not survive the middle of the century, but let’s hope and pray that those who are thirsty will come to eat and drink from our table which has been prepared by the Lord.

Hi Robert,

This is off-topic, but I couldn’t find an email contact for you on your site, so I’m just offering you a couple more articles to critique (in your spare time! :-)). Links to two papers by Dr. Lawrence W. Carrino can be found here (or perhaps you know of an Orthodox critique of this Evangelical Free scholar’s work):

http://christiantruth.com/articles_easternorthodoxy.php

Hi Karen,

I did make a brief comment about Carrino’s posting in Reviews & Responses. I guess rather than burying it in the Comment section I should have turned it into a blog posting. And I guess I should write something in response to his article about apophatic theology. Thanks for the suggestion!

Robert

http://danielbwallace.com/2012/03/18/the-problem-with-protestant-ecclesiology/

Even my old Greek prof at Dallas Seminary sees the holes in evangelical ecclesiology.

Chris,

Thanks! I used Prof. Wallace’s blog posting for my latest posting: “Holy Tradition’s Importance to Canon Formation.”

Robert

Robert,

Forgive me for posting this here but I do not know how else to contact you in order to ask a question.

Is there a search option on your page that I am missing? I am looking for something I know is burried in a combox on one of your posts, but searching through them all is far too much work, considering the in-depth discussions and number of comments.

Thanks,

John

Good stuff Robert! It’s amazing how many international visitors you get.

Regarding this question, I really like reading St. Peter’s epistles which were the catholic epistles- directed at all the early churches instead of only one. St. Peter the bishop of Rome warned against those that make ‘private’ interpretations of scripture. (2 Peter 1) I also love that, being a fisherman, his letters are filled with references to water.

Tom,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! Yes, I’m amazed by all the international visitors too. It’s nice to see how Christ’s teaching has gone out into all the world.

And let us be mindful of the fact that the celebration of Christ’s birth is fast approaching. I hope to have a new blog posting up soon.

Robert

…is “fast” approaching…”

I see what you did there. 😉

Very funny! I didn’t even see the pun until you pointed it out. 🙂

Robert

I stumbled across this article doing some research on the subject of how the words “pastor” and “bishop” found their way into our English Bibles. I realize this article is now some 3+ years old, but thought it wouldn’t hurt to bring a different, yet Bible centered approach to the matter.

Biblically speaking, there is zero distinction between a bishop and an elder. The Greek word for bishop is episcopos, literally, an “overseer.” It’s only appearance as “overseer” is found in Acts 20:28, where Paul says the elders at Ephesus (v 17) were overseers, thus identifying and equating the elders as also being overseers.

In Titus 1:5, Paul commands Titus to “appoint elders in every city,” then goes on to use the term “bishop” (episcopos) interchangeably with an elder, “for a bishop must be blameless.” The idea that Titus was serving as a bishop cannot be reconciled with the text. But, as the King James Version was written in the early 17th century, and the translators were heavily influenced by both the Catholic and Anglican churches, the doctrine and identification of the office of a bishop was preserved in the English translation.

Note the use of “bishop” in its other New Testament appearances:

“Paul and Timothy, the servants of Jesus Christ, to all the saints in Christ Jesus which are at Philippi, with the bishops and deacons” (Phil 1:1).

“A bishop must then be blameless, the husband of one wife… one who rules his own house well, having his children in submission with all reverence” (1 Tim 3:1, 4) [Do modern-day bishops have wives and children?]

(Speaking of Jesus ) “For you were like sheep going astray, but have now returned to the Shepherd and Bishop of your souls” (1 Peter 2:25). This text utilizes two words, both of which are interchangeable with the office and function of an elder.

Of course, from reading this post and the comments, I know that most, if not all, who are in this thread reject the Bible as the sole authority in matters pertaining to religious teaching and practice. I just wanted to note that this article attempted to make a distinction between elders and bishops where the Bible does not. Therefore, one would need to cite some other source of authority rather than appealing to the Bible when teaching this error.

Todd,

Thank you for visiting the OrthodoxBridge. You’re right that Ignatius of Antioch’s understanding of the office of the bishop goes beyond the principle of sola scriptura but that does not make an error. I’m working on an article on the episcopacy that hopefully will be published soon.

Robert

“Biblically speaking, there is zero distinction between a bishop and an elder.”

I would ask you to reevaluate this statement in light of I Tim. 5:17 – “Let the elders who rule well be considered worthy of double honor, especially those who labor in preaching and teaching.” Calvin even comments on this verse with the following statement – “We may learn from this, that there were at that time two kinds of elders; for all were not ordained to teach. The words plainly mean, that there were some who “ruled well” and honorably, but who did not hold the office of teachers.” So if you go back to I Tim. 3:2 it notes that a bishop/overseer must be able to teach, yet we see in 5:17 that not all elders are teachers. Thus it could be said that all overseers are elders, but not all elders are overseers. This is why some, though not all, who maintain an episcopal order would simply describe a bishop as a first amongst equals, his equals being all those in the Presbyterate. You can see a similar instance in I Pet. 5:1 wherein he refers to himself as a “fellow elder”, obviously not all elders were Apostles but it is explicitly stated that all Apostles were elders.

The title may not match perfectly, yet, I ask, what office would Timothy correspond to? He was a person who appointed elders, yet he was not an apostle himself. He had an office in the apostolic place however. He was part of that “third office.” So the churches call that office “bishop” today, and why should they not, as even Peter referred to himself as an elder. Yet Peter was an “elder” who certainly had more authority than other elders! Timothy was in a position to appoint both elders (pastors, bishops if you will) and deacons. The structure is still three way, namely, Timothy’s Position, Elder/Pastor/Bishop, Deacon. Its still a three pronged office system. Therefore, in that day, their was a hierarchy among bishops/elders and eventually the title of “presbyter” became attached to the lesser office, while “bishop” became attached to the greater. Yet the distinction is clear.

David,

You made a good point. It reminds me a family picture where mom and the kids are in the photo but dad seems to be missing. Where’s dad? He’s the one taking the picture!

Robert