Pastor Steven Wedgeworth — Trinity Talk No. 1 (2 November 2009)

Trinity Talk, an Internet radio blog, did a three part series with Pastor Steven Wedgeworth on the Eastern Orthodox Church. The interviews took place on November 2, 16, and 30, 2009. Trinity Talk is a creedal podcast by Uri Brito and Jarrod Richey. Wedgeworth is interim pastor of Immanuel Presbyterian Church (CREC) in Clinton, Mississippi.

First time listeners should be prepared to listen a short commercial then to a fairly lengthy introduction about Trinity Talk before actually hearing Wedgeworth at

5:07. Although presented as interviews, what one hears are a series of questions that leads Pastor Wedgeworth into various topics. This is not a criticism, but more of a heads up alerting the listener to expect something more of a monologue than the dynamic give-and-take of a real conversation.

In this blog posting I will be responding to Pastor Wedgeworth’s November 2 presentation. This review will be structured along the lines of topics than chronology. To facilitate the review I will be referencing his statements by minute and second in the pod cast.

What is the Eastern Orthodox Church?

Pastor Wedgeworth defined Eastern Orthodoxy in terms of institutional structure and political authority. However, he failed to draw attention to the role of Holy Tradition. Wedgeworth’s omission of this fact results in a distorted understanding of Orthodoxy. The bishop’s authority rests upon his holding the Apostolic Tradition. If he were to abandon the Apostolic Tradition or tamper with it, he loses his ecclesiastical authority no matter the correctness of his episcopal ordination. This would be like a Protestant pastor upholding the Bible alone, but denying salvation by grace through Christ.

Wedgeworth’s discussion of the five patriarchates gave too much attention to the influence of the Roman Empire. One almost gets the sense that the Roman Empire incorporated the Christian church into its apparatus. Wedgeworth asserted that soon after Constantine converted to Christianity it did not take long for the church to be ordered along “imperial lines.” He went on to say that these five patriarchal cities were “chosen” (8:39) because it was “politically advantageous” (8:49). It would be more accurate to say that Emperor Constantine recognized the inevitable in the Edict of Milan after the Decian persecutions proved to be too costly and disruptive to the stability of the Roman Empire. Furthermore, the recognition of the five patriarchates did not stem from Emperor Constantine, but the Ecumenical Councils (see Canon 3 of the Council of Constantinople [AD 381] and Canon 28 of the Council of Chalcedon [AD 451]).

Another omission is the conciliar nature of the early church. The early church often settled theological controversy through conciliar action, i.e., the bishops would come together and as a council uphold Holy Tradition. The Ecumenical Councils were regarded as having a higher authority than individual bishops and patriarchs.

Pastor Wedgeworth omitted the Orthodox Church as an Eucharistic community. This can be summed up by Roman Catholic theologian Henri de Lubac’s statement: “The Church makes the Eucharist and the Eucharist makes the Church.” This pithy statement is one that an Eastern Orthodox Christian can agree with wholeheartedly. The Eucharist sums up and ties together the Christian Faith. One could say that alongside apostolic succession through the bishops is liturgical succession through the Sunday Liturgy. For two thousand years the Orthodox Church has been celebrating the Liturgy without break Sunday after Sunday. Thus, an Orthodox Christian today is part of a liturgical tradition that takes him back to time of Athanasius the Great, Irenaeus of Lyons, and Ignatius of Antioch, and beyond that to the original Last Supper. Protestants lack this liturgical continuity having instead a ceremony based upon their reading of the Gospels. They lost this liturgical continuity when they broke off from Rome.

What makes one Orthodox?

Wedgeworth does a good job of succinctly defining an Orthodox Christian as one under an Orthodox bishop (17:50). If I ever have doubts about someone claiming to be Orthodox I ask two questions: (1) Who is your bishop? and (2) Is he in communion with the Patriarch of Constantinople?

However, Wedgeworth gives an imbalanced picture by approaching Orthodoxy principally as “authority structure” (17:37). In contrast the church as “authority structure,” Bishop Kallistos Ware defined the Orthodox Church as communion. In The Inner Kingdom Ware cited Lev Gillet:

An Orthodox Christian is one who accepts the Apostolic Tradition and who lives in communion with the bishops who are the appointed teachers of this Tradition. (page 14; italics in original)

Where Western Christianity and Protestantism put a premium on faith as intellectual understanding, Eastern Orthodoxy places more emphasis on relationship and communion. To receive Communion in the Orthodox Church means that one accepts Apostolic Tradition, e.g., the Ecumenical Councils, the Liturgy, the Nicene Creed, the icons, Mary as the Theotokos etc. It also means that one accepts the bishop as the recipient and guardian of Apostolic Tradition. Both the bishop and the laity are bound by Apostolic Tradition. The bishop has authority in the church so long as he upholds Tradition, but if he attempts to modify Tradition he loses that authority. This is a subtle nuance that Pastor Wedgeworth failed to convey in his interview.

Filioque Clause — “And the Son”

The Filioque clause was a major issue that contributed to the Great Schism of 1054 between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism. While the insertion of the phrase “and the Son” into the third section of the Nicene Creed about the Holy Spirit: “Who proceeds from the Father (and the Son)” may seem like a tempest in a teacup for some, for the Eastern Orthodox this is a major concern.

Pastor Wedgeworth seems to be unaware of the role of conciliarity in the early church. Early pre-Schism popes were theologically and ecclesiastically Orthodox. They resisted attempts to amend the Nicene Creed. The autarchic papacy independent of the Ecumenical Councils and other patriarchates represents a break from the theological method of the early church. The Orthodox Church’s refusal to alter the Nicene Creed is a sign of its continuity with the early church. The decision to unilaterally revise the Nicene Creed through the insertion of the Filioque clause implied the Pope’s belief that he held an authority equal to or higher than the Ecumenical Councils. Protestantism’s cavalier attitude to the Filioque controversy reflects its operating on an all together different theological principle — sola scriptura.

Wedgeworth statement that he does not see it as a “church dividing issue” (12:58) makes sense in light of his abstract and ahistorical approach to doing theology. This theological method has roots in medieval Scholasticism which saw theology in terms of propositions and syllogisms logically organized, and the Humanist movement which saw theology in terms of an critical, scientific reading of the biblical text. This blind spot in Wedgeworth is all too common among Protestants and shows much they have been shaped by the Western theological method. So while Wedgeworth displays a degree of awareness exceptional among Protestants, until he grasps the Eastern Orthodox approach to theology, e.g., the role of Holy Tradition and conciliarity, he will not be able to adequately describe and address the differences between the Reformed and the Orthodox theological traditions.

Council of Florence (1438-39)

Wedgeworth’s mention of the Council of Florence shows an exceptional awareness of Orthodox history (18:21). But his attributing the repudiation of the Council of Florence to the Patriarchate of Moscow and his statement that the Patriarch of Moscow excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople makes me wonder: What has he been reading?? Given that the Orthodox delegates repudiated the agreement soon after they returned home raises question as to whether the Patriarch of Moscow did in fact excommunicate the Patriarch of Constantinople as Wedgeworth claims (18:55). I challenge Pastor Wedgeworth to substantiate his claims.

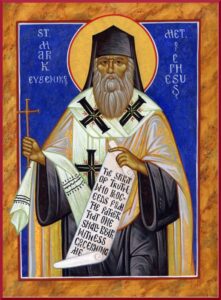

There are two significant omissions in Wedgeworth’s account of the Council of Florence controversy: (1) the role of St. Mark of Ephesus and (2) the role of the monastics and laity in the rejection of the council. The omission is troubling given the fact that Mark of Ephesus was mentioned several times in Kallistos Ware’s The Orthodox Church (see pp. 71, 203, 213) and he is mentioned in other history texts as well. This throws into question Pastor Wedgeworth’s church history research.

The Council of Florence debacle underscored the importance of Tradition in Orthodoxy. It showed that even if Orthodox hierarchs — bishops and patriarchs — were to go astray, the laity will rise up in arms to defend Holy Tradition. This event challenges Wedgeworth’s depiction of Orthodoxy as merely an “authority structure.” If that had been the case, then the Patriarchate of Constantinople would have become a Uniate Church soon after. The Council of Florence controversy underscores the fact that Orthodox polity rests on Apostolic Tradition, not institutional power. The Orthodox will not stand by deferentially if Tradition is compromised but will rise up in defense of the Faith received from the Apostles.

Oriental Churches

Wedgeworth discussed briefly the diverse collections of Oriental churches besides the Eastern Orthodox, e.g., the Copts and Nestorians (19:40). He states that if the Bishop of Constantinople did not recognize you, you are not in the true Church (21:38). Technically Wedgeworth is correct but he is glossing over the complexity of the situation. Those who are not familiar with Orthodoxy may assume that the Patriarch of Constantinople exercises top-down authority over all the Orthodox Churches. This overlooks the principle of autocephalous — self governing — churches. Closer to home, the fact is that the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) actively participates in Orthodox life in America despite Constantinople’s reluctance to recognize it’s autocephaly.

Here in Hawaii when Fr. John, the priest of the Greek Orthodox parish, goes on vacation he often asks Fr. Paul, an OCA priest, to fill in for him. Furthermore, Fr. Paul assists Fr. Anatole at the local Russian Orthodox parish. I also know a Coptic Christian who received Communion at the Greek Orthodox Church. This is based upon the understanding that if there is no local Coptic Church, they can receive Communion at a Greek Orthodox Church with their bishop’s approval.

I find it amusing that Pastor Wedgeworth had to rely on the works of a sixteenth century Protestant theologian, Richard Field (1561-1616), for his understanding of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. I’ve read about the Nestorian and the Monophysite controversies in church history and historical theology. Just as important, I have also interacted with their modern day descendants. I had conversations with the bishop of the local Coptic church and the metropolitan of the local Nestorian church. Let me just say here that the reality is much more complex than what one reads in printed text. Pastor Wedgeworth would do well to spend less time reading books and more time out there meeting with flesh and blood members of these traditions.

Icons & Reformed Iconoclasm

Pastor Wedgeworth does an able job of comparing religious images in the Eastern Orthodox and the Roman Catholic traditions (23:50). He demonstrates a nuanced understanding by discussing icons not just in terms of their being religious images but also with respect to their liturgical use. The chief difference between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions is not the existence of icons but their use in worship. After giving a brief overview of what icons are and how they are intended to be used in the Orthodox tradition, Wedgeworth presents the Reformed objections to the Eastern Orthodox usage of icons.

Wedgeworth notes that Orthodoxy justifies the use of icons on the Incarnation (27:07). This again shows that he done his homework. He rejects the classic Orthodox defense of icons as not making sense to him (27:51). To defend the Reformed iconoclastic stance Pastor Wedgeworth expounds briefly on Moses’ speech to the Israelites in Deuteronomy 4:15 and the Apostle Paul’s speech at the Areopagus in Athens (Acts 17) (28:25). But Wedgeworth oversimplifies the biblical teachings and skews it in a particular direction. There are two strands of biblical teachings with respect to religious images: (1) the polemic against pagan idolatry and (2) instructions for Old Testament worship which included the use of religious images. Wedgeworth neglected to focus his exegetical skills on Exodus 25 and 26, I Kings 6 and Ezekiel 41. These bible passages describe the liturgical use of icons in Old Testament worship. Pastor Wedgeworth is giving his audience a lop sided and biased understanding of what the Bible teaches.

He asserts that Reformed iconoclasm is consistent with contemporary research on Judaism (31:44). It should be noted that Judaism is a complex religious tradition and equating Protestantism’s iconoclasm with that in Judaism is clearly overreaching. Furthermore, Wedgeworth neglected to bring up the recent archaeological findings at Dura Europos that indicate the use of religious images in first-second century synagogue worship.

If there is a serious flaw in Pastor Wedgeworth’s discussion of the Orthodox position on icon, it is his failure to discuss the Seventh Ecumenical Council and the principle of conciliarity. His citing John of Damascus apologia points to a Western way of doing theology: (1) read a theologian, (2) identify a key theological proposition, then (3) critique the proposition on the basis of logic. Wedgeworth’s reliance on abstract theological reasoning based on his reading of biblical and theological texts is at odds with the Eastern Orthodox theological method. Eastern Orthodoxy does not eschew theological reasoning; rather it situates it within Holy Tradition and within the ecclesial context of the Church. There was controversy over the use of icons in Christian worship but that was settled at the Seventh Ecumenical Council. It was at this Council that unity was restored to the Church. Pastor Wedgeworth may claim that allowing for icons (26:40) is “asking for trouble,” but the fact remains that the early church were in agreement in accepting icons and repudiated iconoclasm. What Pastor Wedgeworth has done is declare his independence from the Ecumenical Councils and endorsed an ahistoric doctrine that has no basis in the historic Christian Faith.

“Icon” of Pastor Rick Warren — Saddleback Church

Wedgeworth argues that it is human beings who are the image of God, not flat wooden icons. He cites Calvin’s belief that in light of the fact that people best present the image of God that the Lord’s Supper should be around the table with people looking at other people (33:00). But the fact remains that in most Protestant churches the congregation faces in one direction looking at the minister who is giving the sermon. Ironically, in the case of contemporary worship one finds in mega churches huge jumbotron “icon” of the pastor!

He asserts that Orthodox worship is not focused on the other people in the room but on the icons (32:22). These assertions about Orthodox worship is based upon a superficial understanding of what goes on in the Liturgy. I have found that there is a strong Christ-centered focus in Orthodox worship. The most prominent icons are that of Jesus Christ. Usually Orthodox churches will depict Christ as the unborn Child in Mary’s womb, Christ crucified on the Cross, and Christ the Pantocrator (the All Ruling One). Boredom and distraction is a common problem in churches. When I find myself distracted, I look at the icons and am reminded of their zeal for Christ. But most time my focus is on the icon of Christ up in the front and the prayers of the Liturgy. I found it harder to focus when I was a Protestant in churches with four bare walls.

Conclusion

It is evident that Pastor Wedgeworth has devoted a fair amount of time and energy into understanding Eastern Orthodoxy. One commendable feature of his presentation of Eastern Orthodoxy is the absence of gross caricature and severe distortion one finds elsewhere. If I have a criticism of Pastor Wedgeworth it is that he sometimes gave an unbalanced portrayal of Orthodoxy and doesn’t quite understand the Orthodox perspective on doing theology, but that is understandable given that he is an outsider trying hard to understand a religious tradition that is so different from his. Overall, he did a commendable job.

It is commendable that Trinity Talk devoted a considerable amount of time to the subject of Eastern Orthodoxy. The podcasts reflect the growing awareness of Eastern Orthodoxy among Reformed Christians and concern over growing numbers of Protestants converting to Orthodoxy. Wedgeworth has referred to this as “conversion sickness.” It seems that Pastor Wedgeworth is attempting to inoculate his listeners by exposing them to an attenuated form of Orthodoxy in his pod cast. I admire his efforts to persuade them to remain in the Protestant fold. The Orthodox response is: Come and see! Come to our Sunday Liturgy. Come and experience the ancient historic worship. Instead of reading books about Orthodoxy or listening to a second hand source on an Internet pod cast, come and talk with real flesh-and-blood Orthodox Christians. Let’s get together and talk, and get to know each other.

Robert Arakaki

Good post, Mr. Robert Arakaki. I appreciate your outline of basic Orthodox topics. I wish you had focused a little more on the Filioque doctrine. It’s the major reason people are converting to Orthodoxy; if the Orthodox Church is correct that the Filioque is heresy, then the Orthodox Church is the true Church, for Orthodoxy does a great and grace-filled and excellent work of defending our Lord’s words in John 15:26 and refuting the speculation of Augustine of Hippo, though he remained a Church Father in spite of his error on this matter. We need to understand the Orthodox Church’s nuanced attitude toward Blessed Augustine of Hippo: he is remains a father in the Church, but not all his teaches are accepted as Orthodoxy. He is revered for his piety and his repentance, but repudiated in his mere speculations regarding the Trinity and especially the Filioque matter. God save us. God bless you. In Erie PA Scott R. Harrington

Dear Scott,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! Perhaps I should do a blog posting on the Filioque clause. If I hesitate to call it a heresy, it is because there has yet to be a formal decision made by the Orthodox Church. If there is such a decision, please let me know. I found it intriguing that people are becoming Orthodox because of the Filioque. Perhaps you can let us know about their stories? Thanks.

Robert

Dear friend: Your article is interesting and fair. As for the Eastern Orthodox Church, She is the Body of Christ, in communion with the Body and Blood of Christ (Holy Eucharist) in the Church of baptized/chrismated Orthodox believers (Christians), and in communion with the Holy Spirit Who proceedeth from the Father (John 15:26). Amen. In Erie PA Scott R. Harrington

It is very interesting to see pictures from inside eastern-orthodox church buildings in the US, like the one in Springdale, Arkansas, or in countries where Orthodoxy is welcoming new converts. Although there is an iconostasis and an icon of Lord Jesus Pantokrator, the walls are quite blank. Church buildings in traditional orthodox countries have their own distinct look, most of the times a Byzantine one, and the inside walls are all painted with icons. Also, the believers are usually not sitting down during the Liturgy, as it is full of prayers, and chairs are present in the church only on the margins, for the old people.

Cristian,

It could be that the Orthodox Church in Springdale is a very new one and that the plan is for more icons to be put on the walls. The main thing is for us to look for the major common elements of Orthodox Tradition first then to look for the secondary elements later. As far as people sitting down during the Liturgy, my preference is for the more traditional practice of standing throughout the service. In America some Orthodox jurisdictions are traditional and have a minimum of pews and other jurisdictions have adopted the practice of having pews.

Robert

I have heard it said that Russians first introduced pews in their parishes in order to look more American. This, of course, was when Communism was in control of Russia and many Russians escaped the oppression and went to various places, including the U.S. This, of course, does not mean that Russians in general were welcomed with open arms. In order to not appear too different, they took one route, that of adding pews, as well as others. I recall some even adding American flags in their parishes. I would say that these measures to appear pro-American and no pro-Communism were well intentioned but the actual practice was a bad idea. We should not fear persecution by either Communists or Democracies. My parish is an excellent example of slowly returning to the tradition of standing and having very few pews in the church. My priest removed a row of pews every few weeks until slowly we have pews lining the walls and the back for the sick, infirm, elderly and whatever other reason there may be for sitting (during the homily, for example). Given time, I think we will see more of this in practice. Orthodoxy in America needs time to return to her Roots. Thankfully, this is already happening.

Also, I do notice that even Churches with pews (there’s one about 30 min. from where I go to college) we stand virtually the entire service. The pews get in the way of prostrations during Lent but otherwise, they aren’t really used much. So even churches with pews ought not be judged harshly. I made the that very mistake on my first few visits to St. Elias Orthodox Church. I have since seen a lively community with a priest available to serve Liturgies more often than once a week, especially during feasts occurring on feast days and also Vespers.

John

Grace and peace. We have moved our website to http://trinitytalkradio.com/

and an edited version of the interview is found here without the long, Live intro: http://trinitytalkradio.com/

Many thanks for the interaction.

Rev. Uri Brito

Rather, http://www.wordmp3.com/details.aspx?id=10107

Dear Uri,

Thank you for the correction. Visitors, please note that I have modified the link to the Trinity Talk icon. Also, I have tried to link the icon/pictures in my blog postings to other sites.

Robert

Dear Robert,

I just discovered your website yesterday. I cannot express merely with words how delighted I am in this discovery. Recently, I posted a comment on Father Stephen Freeman’s blog, Glory to God For All Things referring to the Reformed teaching on Imputed Righteousness, i. e. alien righteousness. Father Stephen is not well-versed in the Calvinist tradition, having come from Anglicanism. Then…it seems providentially, I find myself here at your blog. I especially appreciate the irenic nature of discourse that you encourage here. That alone is a rare find on Christian blog sites.

Just to give a brief background, I attended a Reformed church (Baptist) for a decade, and have since become Orthodox two years ago on Lazarus Saturday. I have friends that are still Reformed and hold staunchly to the 5 points and Doctrines of Grace, as they are called. I long to be able to have peaceful and productive dialogue with my dear Reformed friends, who are like family to me. I believe your blog site is a valuable resource in this regard. I will continue to return here often!

P.S.: Have you written a critique on Imputed (alien) Righteousness and its divergence from Orthodox teaching? Our one Reformed friend insists often that this is a non-negotiable doctrine of the Christian faith and must be believed in order for one to be saved.

Dear Darlene,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! Thank you for your positive feedback. I hope you will encourage your Reformed friends to visit this site. My hope is that we will have more conversations between Orthodox and Reformed Christians on this site and out there. I think there is a greater openness to Orthodoxy among Reformed Christians today. But we need to have good answers for their questions.

No, I haven’t written about imputed (alien) righteousness. I agree that it is an important topic that needs to be addressed. The challenge here is the background research needed for the blog posting. Reformed Christianity has some pretty complex doctrines and I often need to do quite a bit of background research before writing up my articles. Your prayers would be very much appreciated. Thanks you!

Robert

Darlene,

Try this for starters. (Not to steal your thunder Robert.)

http://energeticprocession.wordpress.com/2009/05/18/reformed-doctrine-of-imputed-righteousness-refuted/

Robert,

If the Filioque is not a church dividing issue, then why do the Reformed include it in their Confessions? This seems especially strange given that the majority of Reformed exegetes seem to admit that it is not derivable from Scripture alone.

It is interesting to see the boots on the ground adherence to tradition over sola scriptura among the Reformed nonetheless.

I don’t understand the claim that the focus of an Orthodox service is the icons. The focus is very definitely Christ. Icons are used to direct the focus to Christ. If Protestants want to dispute whether icons are allowed, they need to dispute whether icons ought to be used to direct the focus to Christ, rather than deny that Christ is the focus.

I had a similar thought Matthew per ANY physical instrument mediating grace to us, and directing our focus. We Protestants (BB Warfield notwithstanding) would argue that the Bible, Hynms, Prayers, Choir, Pastor/Sermon…are not the REAL focus of our worship — but the Triune God Himself (or particular focus on one person of the Trinity). Like Icons, these are mediating-means to direct us. Per our Robin/Gnostic discussion, any physical/material instrument of mediation, sacramentalizes Creation is some sense…thus sacred space, people and instuments. Now, the Orthodox argue the Fathers formalized this with a special/specific use of Icons in worship — but the use of material, instumental means to mediate grace and directing our attention, seems undisputable, no?

Yes, I think it is undisputable.

But my point was a little different. Icons may be wrong, but they are not the focus, Christ is. If Icons are wrong it is not because they distract the focus from Christ, but because they illicitly focus us on Christ.

The result of this, and the reason it’s important to this discussion, is that Wedgeworth’s argument is rhetorically to strong, and hence is unsound. He wants to argue against icons in worship, and does so by stating that they are not the focus of Orthodox worship, not Christ. Now granted, if icons were the focus, and Christ was not, the Orthodox would be doing something illicit. But icons are not the focus, and if Orthodox are doing something illicit, they are doing something entirely different from what Wedgeworth accuses them of, and hence it is wrong for entirely different reasons. More importantly, the rhetorical punch is taken out. It is far more difficult rhetorically to claim that icons are wrong, though the cause us to focus more fully on Christ; than to argue that something is wrong because it distracts from Christ.

“He wants to argue against icons in worship, and does so by stating that they are not the focus of Orthodox worship, not Christ. ”

That should be “He wants to argue against icons in worship, and does so by stating that they are the focus of Orthodox worship, not Christ.

Well said Matt. My point was simply that if Stephen is right and Icons, of necessity, distract our focus from Christ to the Icon — then our Orthodox brothers might argue we are on the hook with them…in the mediating use of our Bibles, Pastors, hymns, prayers…not to mention water, bread and wine. We might end up arguing whom is more careful to stucture the use of such things to avoid pride, vainglory, and self-service — or all must lost behind the liturgy and “Icon” to keep our focus where it belongs?

Yes. I agree with you.

Robert,

I think one of the questions that arises out of the Reformed – Orthodox discussion is the definition of idolatry. At least in my understanding of Reformed theology, idolatry is the use of any visual representation of God or gods, per Exodus 20 (“you shall not make ANY graven images to bow down or worship them…” paraphrased). So, while the OT Jews may have/did direct themselves towards the Temple to pray, they were not bowing down to the Temple or worshiping the Ark, the Temple/Ark just happened to be there where God was (I am, of course, radically oversimplifying things — forgive me). Post-incarnation, short of a specific command that abrogates or changes the OT prohibition on veneration of images, Reformed see no reason to adopt visual imagery — whether as an idol or a help or in an iconic sense.

As far as I can see within the Orthodox world (and I remain a curious outsider looking in), there seems to be a fairly fine distinction between icons and idols (one that I’m hoping you will spell out for me). Whenever idols are referenced here at the Bridge (at least as far as I can remember), the word “pagan” appears before them. Does this mean that a thing is an idol only when used for foreign gods? Can there be an idol of the one true God? Is it possible for Orthodox usage to fall into idolatry, shifting the focus from Christ to the icon itself?

As always, I am trying to present my own thoughts and so if I have misrepresented or offended, please accept my apologies in advance.

Russ

Russ,

Your question about the difference between icons (eikon) and idols (eidwlon) would require an extensive word study of the Bible plus a thorough etymological analysis. I took a quick look at Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament and it shows that ‘eidwlon’ is used with reference to images of heathen deities (vol. 2 p. 377). Where the word ‘idol’ seems to be restricted to pagan deities, the word ‘image’ is used more broadly. Its usage can be applied to to God, Jesus Christ, and Adam and Eve (see Genesis 1:27, Colossians 1:15) (vol. 2 pp. 381-397).

My response to your question: “Can there be an idol of the one true God?” is to ask another question: “Is it possible to misrepresent God using a visual representation?” My answer to the second question from an Orthodox standpoint is: Just as it is possible depict Jesus Christ correctly, so it is also possible to depict Christ incorrectly. Not any icon of Jesus is an Orthodox icon. Orthodoxy has rules about what constitutes a proper icon of Christ. If you want to an un-Orthodox icon of Christ, I suggest you visit a more liberal Christian or Roman Catholic bookstore. I once saw an ‘icon’ of a New Age Christ in a bookstore.

Your question: “Is it possible for Orthodox usage to fall into idolatry, shifting the focus from Christ to the icon itself?” strikes me as superficial. We can get caught up debating the use of images in Christian worship and overlook the invisible idols in our Christian community. Jesus warns in Matthew 6:24 that one cannot serve both God and Money. In Philippians 3:19 Paul laments over those whose god is their stomach. Idolatry consists not just in our theological beliefs about God but also whom we will serve, i.e., what we give priority to. If a Christian gives priority to his work or his hobby or his political affiliation OVER Christ, then he or she has fallen into the sin of idolatry. It is a constant struggle in the Christian life to truly serve God and to have no other gods in our life. One can be doctrinally orthodox and still fail to enter the kingdom of heaven (see Matthew 7:21-23). The Orthodox Church stresses repeatedly that we need to constantly repent of our sins, follow the teachings of the Church, and work out our salvation. Lent is a good time for us renew our love for Christ and to root out the idols in our life.

With respect to the Reformed tradition’s insistence that there must be a specific command that abrogates or changes the OT prohibition on veneration of images, my response is: You mean the incredible act of the Incarnation of the Son of God is not enough?!? John of Damascus wrote: “How does one paint the bodiless? How can you describe what is a mystery? It is obvious that when you contemplate God becoming man, then you may depict Him clothed in human form. When the invisible One becomes visible to flesh, you may then draw His likeness.” On Divine Images Section 8. This position was affirmed by the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II) in 787. The iconoclastic position did not surface again until the Protestant Reformation repeated the earlier iconoclastic arguments that had been addressed, refuted, and repudiated by the Seventh Ecumenical Council. For the Orthodox the matter has already been settled once and for all. The Reformed Christians have a choice: They can either accept the historic Christian faith or they can go their own independent way. I’ve given the biblical rationale for the use of icons that is congruent with the early church fathers and Nicea II in the “Biblical Basis for Icons.” Calvin and others have chosen a quite different reading of Scripture that diverges from the early Church and flout the Seventh Ecumenical Council. This is much like a lawyer choosing to disregard the ruling handed down by the Supreme Court on the Constitution. They have the appointed authority to rule on the Constitution, the individual lawyer does not. Matthew raised the issue about whether icons are distracting or illicit. The Seventh Ecumenical Council settled that decisively. Please pardon my frank, no punches pulled answer.

Robert

Robert

Robert,

It is fine to be punchy, I can take that. I would caution against calling any honest question “superficial,” though. That muddies the waters against further dialogue.

I thank you for the Kittel reference, although I don’t think it is ultimately what I was looking for. It seems clear from Exodus 20 that an “image” can be used in a negative sense, as what is customarily called an idol. Maybe the Bible’s own polemic against paganism restricts the use of the word “idol” to the interaction between pagans and Israelites, but the concept may come over into Israelite religion through the word “image.” I’m not even sure I’m fully understanding what I want to ask in this context, so maybe I’ll set it aside until I have clarified it further.

Concerning the “superficial” question, I do agree with you that we make all sorts of things idols in our lives and we should, with the help of the Church, root them out. That doesn’t negate that in our world real and visible idols still do exist, even if they do not go by that name. It seems to me that we are worse off today with visible idolatry than they would have been in Scriptural and Patristic ages, since at least then they knew the various icons/images/idols were meant to represent gods or heroes or saints or whatever. Now, we call them “logos” or “symbols” or just “graphic design” and we venerate them (we even go to the “genius bar” at the Apple store — “genius” being what one would burn incense to in Caesar worship). So the images used in Christian worship are particularly important to discuss and debate: they set the tone for our whole lives. If we have the right images, then the other worldly or even demonic icons of our age will start to appear as such. So when you say: “We can get caught up debating the use of images in Christian worship and overlook the invisible idols in our Christian community,” I don’t think the two can be separated.

Let me take a step back for one moment — I think some of my own presuppositions need to be spelled out (I’m going to use the language of R.J. Rushdoony here, which I think he got from C. Van Til, because I find it useful): even for the Reformed, it isn’t the question of images versus no images, but whose (or which) images. Even with four bare white walls (and I can think of only one Reformed church that I’ve ever been in that would fit that stereotype), there are images. The “icon of the pastor” (as you fitly called it), the “icon of the Bible” as it is raised up in the podium/lectern, the “icon of the sacrament” whenever it happens, and the “icon of the people” all around us. Certainly these aren’t absent from an Orthodox service (and I did finally find the chance to attend an Antiochan service over Thanksgiving). By locating the imagery in these things, the Reformed do have at least a chance to see the glory of Christ reflected and refracted in worship. The problem, it seems to me, is that we are usually not made conscious of these symbols and icons: we often do not see the glory of Christ in our fellow worshiper nor in the sacrament (especially if it is understood only “symbolically” instead of as the real Spiritual body of our Lord) because we don’t know to look there. If our eyes are attuned, though, we are fulfilling — at least in part — the spirit of the 7th Council to venerate what are truly holy icons of God’s work in Christ among us. Whether or not we use other icons of past (yet always present) saints or of Christ can then be debated, as long as we (both sides, Reformed and Orthodox) understand that we are both iconodules, just in different ways. We need these “icons” to help us fight the constant barrage of imagery that accompanies our modern idolatries (such as mammon or political affiliation, etc.).

All that said, I think we are in more agreement than disagreement.

Russ

Russ,

I appreciate your kind and civil response. I think I used the word “superficial” because I was reacting against over theologizing about icons and Christian worship. All too often we ignore or are blind to the imageries around us, secular and religious. I think you will enjoy reading Antony Ugolnik’s The Illuminating Icon. It was written by an Orthodox English professor of Russian immigrant parents during the Cold War. It contains a sensitive and reflective analysis of religious images during a time when societies are saturated with secular and political images.

I’m glad to hear that you had a chance to visit an Antiochian service during Thanksgiving. If you have the opportunity, I would encourage you to visit an Orthodox church this coming Sunday (18 March 2012). This Sunday is known as the Sunday of the Veneration of the Cross. It would give Protestant visitors an interesting way of comparing how Orthodox Christians honor Christ’s death on the cross with their own. Both traditions recognize the significance of the cross for our salvation but do so in quite different ways.

Let us seek to honor the icons whether two-dimensional ones hanging on the wall or three dimensional flesh-and-blood icons sitting next to us at church or at home or at work/school.

Robert

Russ,

Not sure this will answer all your questions, but Robert dealt with these linguistic issues in his article here where he interacted with Calvin on Icons. Interesting reading for a Protestant. https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxbridge/?p=119