Christ’s Descent Into Hades (Source)

Christ is Risen! Truly He is Risen!

Dear Folks,

The year 2025 has gotten off to a tumultuous start here in the United States as well as in other parts of the world. We do not know where history is taking us, but we do know that the God of history has entered into history in Christ’s Incarnation and has altered the course of history decisively in Christ’s third-day Resurrection. For Orthodox Christians, Christ’s resurrection is our anchor in these times of uncertainty.

The one constant in human history, even with the repeated rise and fall of kingdoms, societies, and civilizations, has been the reign of death over all humanity. The inexorable approach of death has long haunted humanity causing many to seek refuge in God. The Christian religion has presented Jesus Christ as God’s answer to the problem of death. Protestants and Orthodox have rather different understandings of death and Christ’s Resurrection. Where many Protestants and Evangelicals view death as punishment for our sins, Orthodoxy view death as our great enemy. Protestants may be surprised at the Orthodox understanding, but this is consistent with the biblical teaching that death is the great enemy that needs to be vanquished. The Apostle Paul wrote:

The last enemy that will be destroyed is death.

(1 Corinthians 15:26; NKJV)

The understanding of death as our enemy is consistent with the Christus Victor paradigm of salvation. In this theological paradigm, Christ is the Hero who undertakes a rescue mission into the depths of Hades liberating fallen humanity from the tyranny of Death.

The theme of Christus Victor runs through the Bible. It can be found in the Old Testament. In Isaiah 25 is a prophecy that describes how God would in the future destroy death.

6 On this mountain the Lord Almighty will prepare

a feast of rich food for all peoples,

a banquet of aged wine—

the best of meats and the finest of wines.

7 On this mountain he will destroy

the shroud that enfolds all peoples,

the sheet that covers all nations;

8 he will swallow up death forever.(Isaiah 25:6-8; NIV, emphasis added)

The Christus Victor motif is likewise present in the New Testament. We find in the book of Hebrews Christ’s triumph over Death and the Devil:

14 Inasmuch then as the children have partaken of flesh and blood, He Himself likewise shared in the same, that through death He might destroy him who had the power of death, that is, the devil, 15 and release those who through fear of death were all their lifetime subject to bondage.

(Hebrews 2:14-15; NKJV, emphasis added)

Hebrews 2:14 teaches us that through the Incarnation, that is, by taking on human flesh, God the Son was able to share in human existence and experience death on our behalf. One could say that God the Son entered into the boxing ring to fight Death on behalf of humanity. This is substitutionary atonement–Christ taking our place in the boxing ring. By taking our place–suffering death on our behalf, Christ’s victory became our victory. In the Holy Saturday Liturgy, I came across a hymn concerning Death’s encounter with just-crucified Jesus.

Today Hades cried out groaning: “My authority is dissolved; I received a mortal, as one of the mortals; but this One, I am powerless to contain; with Him I lose all those, over which, I had ruled. for ages I had held the Dead, but behold, He raised up all.” (Greek Orthodox Holy Week and Easter Services, p. 415)

Knowing this results in the explosion of joy on late Saturday night/early Sunday morning in the climactic Easter Liturgy, when after a few minutes ot total darkness inside the sanctuary the priest comes out holding the Paschal candle shouting: “Christ is Risen!” And the congregation shouts back: “Truly He is Risen!” Over the next several weeks, the Orthodox Faithful will greet each other with: “Christ is Risen!” and respond with: “Truly He is Risen!”

A New Perspective

Christ’s third-day Resurrection imparts to the Orthodox Christian a new perspective on world events. Christians are in the world but not of the world (see John 17:11, 14-16). The Apostle Paul reminded the Christians in Colossae that their citizenship is in heaven (Colossians 3:20). The early Christians were keenly aware of their dual citizenship. We read in one of the earliest post-apostolic writings, The Letter to Diognetus:

But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. (Letter to Diognetus 5.4-5; emphasis added)

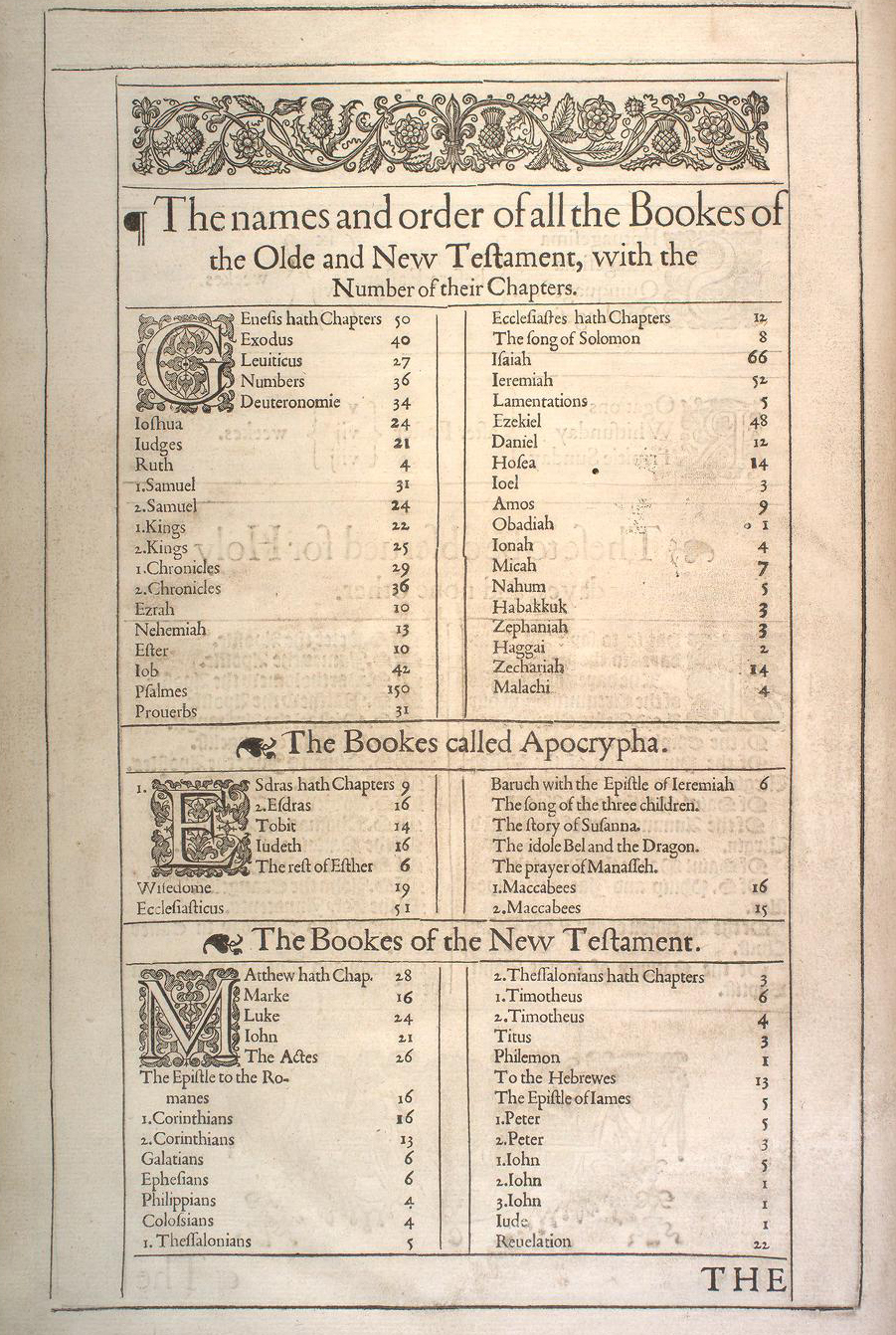

From these sources we learn that Christians possess a stereo vision of the world–our American identity is overlaid with our citizenship in the kingdom of God. I became aware of this fact a few years back when I venerated the Kursk Root Icon which dates back to 1295. Upon seeing the icon, I was struck by the fact that this particular icon, which is relatively recent by Orthodox standards, is five centuries older than the United States, which was founded in the late 1700s. To be Orthodox is to belong to an ancient Church that has seen the rise and fall of many kingdoms and nations, and will outlive them all–even the United Stats of America is a mortal entity that will eventually fade away into the backdrop of human history. A stark reminder of this fact is Great Britain of which it was believed that the sun would never set, yet today is fading into the sunset. I grew up during the Cold War in which the U.S. faced off against the mighty U.S.S.R. until the unexpected collapse of Communism in 1991. And, it was just a hundred years ago that the great Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Russian Empire all vanished from the face of the earth. The mortality of these political entities all confirm Isaiah’s prophecy about the shroud of mortality that covers all nations. The Book of Isaiah is full of prophecies about the imminent demise of nations and peopes, and about the coming of the Messiah (the Christ). The only eternal entity is the Church, which Christ promised the gates of Hell would never overcome. One sign of the Church’s permanence can be seen in our worship–we still use the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom which dates back to the fifth century.

Recently in my research, I came across a passage that sketches a very early political theory by a Church Father. Irenaeus of Lyons in Against Heresies explains that as a result of the Fall the human race fell into a state of disorder such that man came to “look upon his brother as his enemy.” This echoes Thomas Hobbes’ political science classic work Leviathan in which the natural state of man is described as “a war of all against all.” Irenaeus then proceeds to teach that God instituted government to restore order to humanity. He points out that since people were not prepared to acknowledge the fear of God, they would need to be induced to conduct themselves decently and orderly out of fear of the government’s sword–the power to punish and kill.

2. For since man, by departing from God, reached such a pitch of fury as even to look upon his brother as his enemy, and engaged without fear in every kind of restless conduct, and murder, and avarice; God imposed upon mankind the fear of man, as they did not acknowledge the fear of God, in order that, being subjected to the authority of men, and kept under restraint by their laws, they might attain to some degree of justice, and exercise mutual forbearance through dread of the sword suspended full in their view, as the apostle says: “For he beareth not the sword in vain; for he is the minister of God, the avenger for wrath upon him who does evil.” (Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies ANF Vol. 1 5.24.2;, p. 552) (Emphasis added.)

Irenaeus’ understanding of government echoes the ancient Chinese concept: the Mandate of Heaven–although given great power by God (Heaven) the emperor was morally obligated to use it for the good of the people. And like the Chinese theory of the Mandate of Heaven, Irenaeus believed that should the ruler abuse his power through corruption, impiety, and tyrannical rule, “they also perish.” The American concept of “popular sovereignty”–that is, the authority of government comes from the people–is very this-worldly. Irenaeus give us a different political theory–that political authority ultimately comes from God (see also Jesus’ dialogue with Pilate in John 19:11). And that from a Christian point of view, governmental authority cannot be divorced from justice and morality. Just as bad people ought to fear governmental authority, so too governmental authorities ought to carry out their duties out of fear of God. According to Irenaeus, tyranny–cruel and oppressive government–will come under divine judgment.

And for this reason too, magistrates themselves, having laws as a clothing of righteousness whenever they act in a just and legitimate manner, shall not be called in question for their conduct, nor be liable to punishment. But whatsoever they do to the subversion of justice, iniquitously, and impiously, and illegally, and tyrannically, in these things shall they also perish; for the just judgment of God comes equally upon all, and in no case is defective. (Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies ANF Vol. 1, Book 5.24.2;, p. 552)

It is concerning that there are some who regard governent as a problem, a burden on the people. One gets the sense from some of the more extreme points of view that government is an evil to be eradicated. As Orthodox Christians we ought to take heed of Irenaeus’ teaching on governmental authority. We learn that government (earthly rule) has been established “for the benefit of nations.” The phrase “benefit of nations” is not spelled out in detail but we can guess that it means for the benefit of the general public, not for the enrichment of the few. Governments are called to establish laws that “keep down the excess of wickedness” and encourage people to live quiet, peacable lives. Irenaeus uses the vivid imagery of government preventing people from “eating each other like fishes”! This can be read as government preventing or constraining ruthless Darwinian competition. In the divine order, society consist of people living and working together, not eating each other.

Earthly rule, therefore, has been appointed by God for the benefit of nations, and not by the devil who is never at rest at all, nay, who does not love to see even nations conducting themselves after a quiet manner, so that under the fear of human rule, men may not eat each other up like fishes; but that, by means of the establishment of laws, they may keep down an excess of wickedness among the nations. And considered from this point of view, those who exact tribute from us are “God’s ministers, serving for this very purpose.” (Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies; ANF Vol. 1 Book 5.24;2; p. 552) (Emphasis added.)

Irenaeus’ teaching on governmental authority does not stand alone but should be understood in light of the prayers the Church offers in the Liturgy in the opening Litany of Peace:

For our country, the president, all those in public service, and for our armed forces everywhere, let us pray to the Lord. (Source; emphasis added)

In the Liturgy, the Orthodox faithful pray, not just for the top echelons of government, but also for the rank and file military personnel and civil servants. Orthodox ethics is also based on solidarity with our fellow humans, which is why we pray for “the sick, the suffering, and those in captivity.” We find this in the opening Litany of Peace as well:

For those who travel by land, sea, and air, for the sick, the suffering, the captives and for their salvation, let us pray to the Lord. (Source; emphasis added)

Ultimately, we pray for God’s will to be done here on earth as it is in heaven. Everytime Orthodox Christians attend the Liturgy, they are renewing and reaffirming their citizenship in heaven and renewing their allegiance to Jesus Christ the Ruler of All.

This addendum–A New Perspective–was not part of my original plan for the 2025 Paschal blog posting; however, recent events in the United States and around the world have led me to change my mind. I wrote it for my American readers and also for my international readers as well. Regardless of our nationalities, Orthodoxy transcends national identities–we belong to each other and our ultimate allegiance is to Jesus Christ the Pantocrator. Recently, several people have expressed to me their fear and deep concern about recent events in the United States. As I listened, I was reminded of 2 Thessalonians. In this letter, the Apostle Paul was writing to a group of Christians that recently become “unsettled or alarmed” (2 Thessalonians 2:2). Paul reminded them to “stand firm” on Apostolic Tradition (2 Thessalonians 2:15).

The Orthodox Church, through the Liturgy and through the Church Fathers, offers the Orthodox Faithful the spiritual resources to stand firm in these troubled times. The challenge of chaos and social upheavals may tempt one to compromise and resort to expediency. Even as circumstances change, Orthodox Christians are called to not abandon the teachings of Christ and to remember that our ultimate allegiance is to Jesus Christ the Pantocrator (the Ruler of All). My prayer is that Orthodoxy not be seen as aligned with a particular political party or with a particular ideology. But that no matter which group an Orthodox Christian may be part of, they will be seen as citizens of the Kingdom of God. Likewise, my prayer is that when discussing politics, Orthodox Christians will reflect the teachings of Irenaeus of Lyons and the prayers found in the Litany of Peace.

Lastly, as Orthodox Christians celebrate Christ’s triumph over Death, let us remember Palm Sunday when Christ entered Jerusalem on a donkey instead of a war horse and his telling his followers that he came as the Suffering Servant who came to serve others. And, let us learn from the tragic failings of Judas Iscariot (who once was part of the Christian community), the Jewish leaders and the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate, who succumbed to the temptations of power seeking, moral compromise, self-justification, and expediency.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments