“2016 State of American Theology Study,” a survey sponsored by Ligonier Ministries and carried out by LifeWay Research, gives an intriguing and sometimes disturbing overview of what Americans believe. Care was taken to ensure that the 3,000 people who took part in the survey reflected the U.S.’s diverse population.

The results of the survey have generated considerable discussion among Protestants. In a recent article in First Things, Matthew Block bemoaned the spread of heretical beliefs among American Evangelicals. He notes that among “Evangelicals” – those who hold to core Evangelical beliefs – 71 percent believed Jesus to be a created being and 56 percent believed the Holy Spirit to be an impersonal force.

The results of the survey have generated considerable discussion among Protestants. In a recent article in First Things, Matthew Block bemoaned the spread of heretical beliefs among American Evangelicals. He notes that among “Evangelicals” – those who hold to core Evangelical beliefs – 71 percent believed Jesus to be a created being and 56 percent believed the Holy Spirit to be an impersonal force.

Mr. Block’s article just scratched the surface of the survey. Other significant findings include: (1) the majority of Americans (60 percent) agree with the statement “Heaven is a place where all people will ultimately be reunited with their loved ones;” (2) 49 percent of Americans agree with the statement “Sex outside of traditional marriage is a sin;” and (3) 77 percent of Americans agree “an individual must contribute his or her own effort for personal salvation.” (See the Research Report pages 3-5) To put it another way, 60 percent of Americans are universalists, almost half do not think fornication to be sin, and more than three quarters believe in salvation by works.

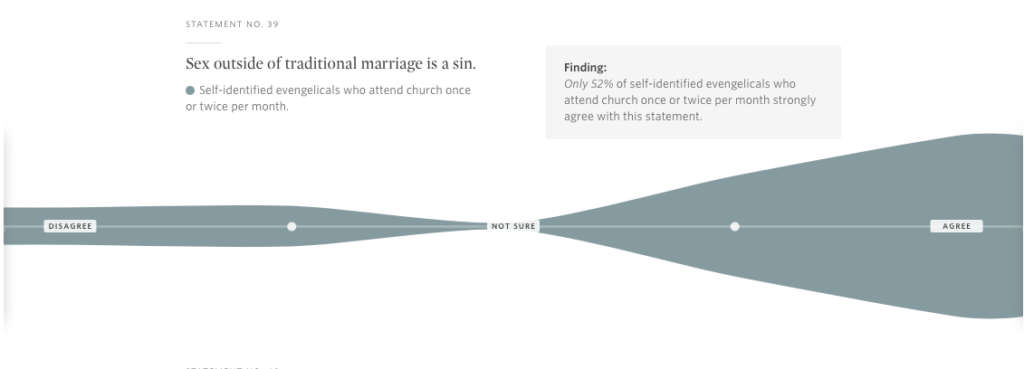

While reading the survey findings it is important to note that two groups were being surveyed: Americans in general and Evangelicals. Thus, it behooves the reader to make sure that the percentages enumerated are applied to the right group. For example, the findings in the previous paragraph pertain to Americans in general, not American Evangelicals in particular. One need not be surprised if a substantial percentage of the American public are said to hold deviant beliefs; however, it should be a matter of concern if a similar percentage of Evangelicals hold deviant beliefs. For example, in the section “Ethics” (Statement No. 39) it was found that only 52 percent of self-identified Evangelicals agreed with the statement that sex outside of traditional marriage is a sin – a startling shift away from historic Christian morality.

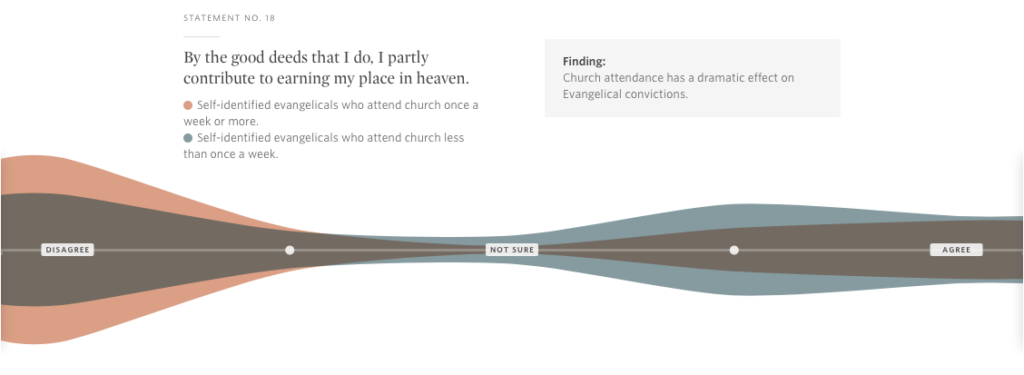

On the other hand, in another section (Statement No. 18) it was found that the more often one attends church the more likely one is to disagree with the statement that one can contribute to one’s salvation through good works – affirming salvation by grace alone, through faith alone which are core Protestant beliefs. It should be noted that the graphics are not accompanied by percentages. For scrupulous researchers this is quite frustrating.

Some Caveats

Readers who wish to examine the survey research and analysis are advised to visit the following sites: (1) the 26 page Research Report (White Paper) which summarizes the findings (2) the 103-slide PowerPoint presentation of survey results, (3) Bob Smietana’s easy-to-read overview, and (4) Ligonier Ministries’ analysis.

I found the survey very informative but noticed one important omission, the religious identity of the respondents. In the latter half of the PowerPoint presentation, the responses were broken by region, ethnicity, economic status, and age, but not by religious affiliation. It would be helpful to know how Evangelicals stand in relation to liberal mainline Protestants, Roman Catholics, Mormons and Jehovah Witnesses, and secularists. This kind of demographics profile would help make sense of the data especially as America becomes increasingly pluralistic with the rise of the so-called “Nones” and the growth of the non-Christian population.

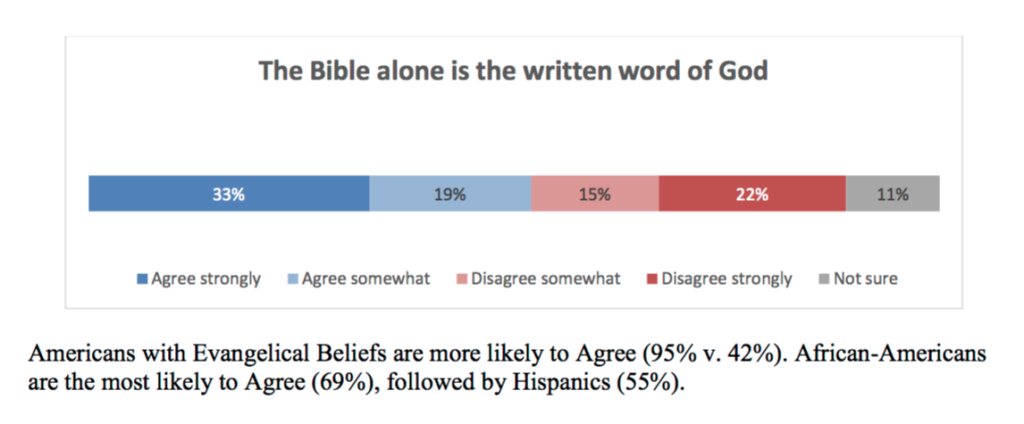

Another matter of concern is the confusing manner in which numbers are presented. The Research Report finds that 95 percent of Evangelicals affirm the statement: “The Bible alone is the written word of God.” In contrast, only 42 percent of the general American population believe that. However, I find this puzzling because when I add 33 percent of “strongly agree” with 19 percent for “agree somewhat” I get 52 percent. The inconsistent numbers presented raise questions about the validity of the survey.

p. 15 Link

Evangelicalism Falling Apart?

As a Protestant convert to the Orthodox Church, I found the responses on how Evangelicals understand the church striking. The responses suggest that American Evangelicalism, at least in its corporate expression, is falling to pieces – becoming increasingly fragmented doctrinally and ecclesially.

p. 19 Link

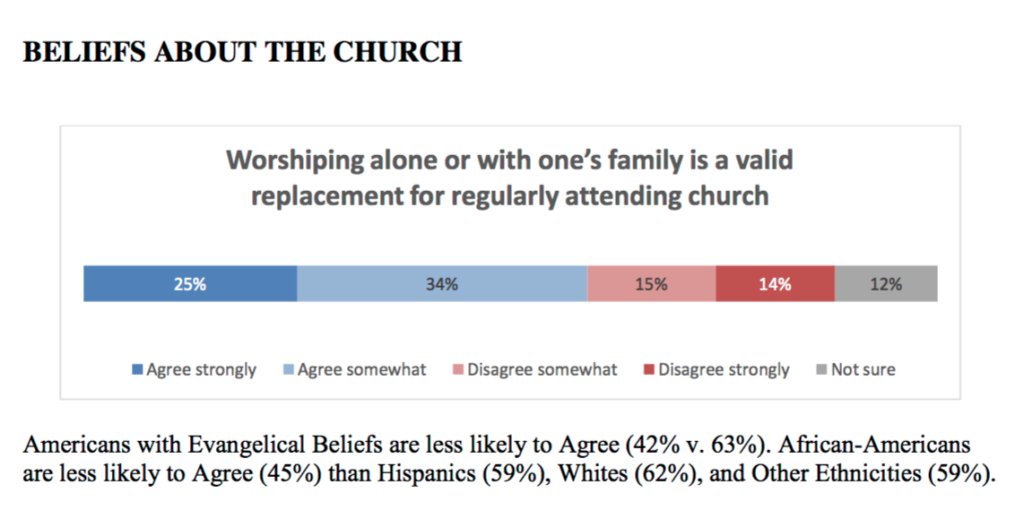

In response to the question: “Worshiping alone or with one’s family is a valid replacement for regularly attending church,” some 59 percent of Americans agreed, while 29 percent disagreed. In the caption underneath the graphic, LifeWay noted that Evangelicals were less likely to agree, giving the percentages of 42 percent versus 63 percent. First, even if 42 percent of Evangelicals agree that’s still quite a high percentage that has abandoned the traditional view of the Church. Second, I have no idea what the number 63 percent refers to. I don’t think it refers to those who agree versus those who disagree because the total should come close to 100 percent, not the 105 that results from adding 42 to 63. This is where the LifeWay survey falls short. Greater precision is needed in the presentation of the findings in order for readers to benefit from the research project.

This devaluing of church membership seems to support the rise of the “Nones” and the “Dones.” See Mark Sandlin’s article “The Rise of ‘The Dones’ as the Church Kills Spiritual Community” in which he attempts to explain how the current dysfunction in Evangelical churches is alienating and driving away committed people. In his explanation of the emergence of the “Dones” – unaffiliated believers, Mr. Sandlin writes:

The Church is killing spiritual community or at least killing it in an ever-growing portion of our population. The Dones’ experience with the Church killed their desire to ever go to that place of spiritual relationship in community again.

He elaborates:

The Dones are right. The communities making up far too many churches are much more soul sapping than they are spiritually nurturing.

This growing disenchantment with church life, while quite different from doctrinal orthodoxy, ought to be of concern to Christians. Christianity’s future in America depends not just on right doctrine but also on life in community.

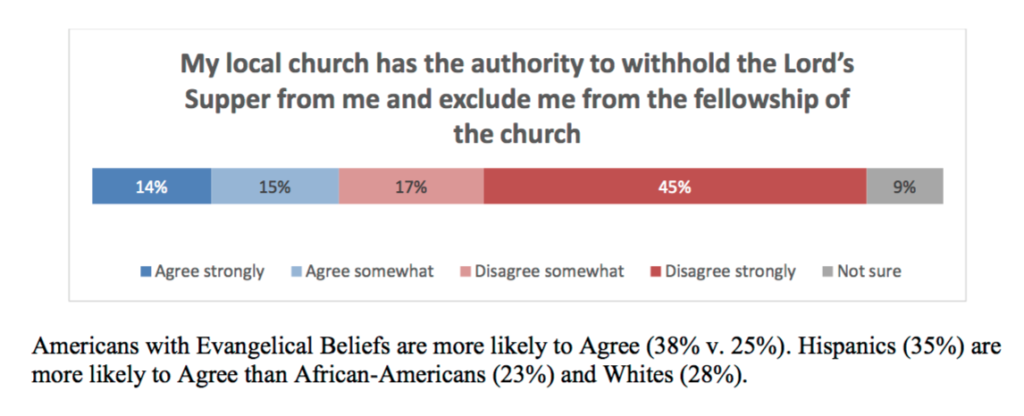

What really caught my attention were the responses to the question: “My local church has the authority to withhold the Lord’s Supper from me and exclude me from the fellowship of the church.” Some 45 percent of Christians who attended church on holidays or more frequently “disagreed strongly,” while another 17 percent “disagreed somewhat.” Those who agreed, strongly or somewhat, comprised only 29 percent. It seems that Evangelicalism’s emphasis on a personal relationship with Christ has taken on more extreme forms, with many unwilling to accept the authority of the Church.

p. 20 Link

This is contrary to the historic Protestant understanding of the three marks of the Church: the pure preaching of the Word, the pure administration of the sacraments, and church discipline (See Belgic Confession, Article 29). What is concerning about this rejection of church discipline is that it constitutes a rejection of the Church as the Mother of the faithful. It may surprise Evangelicals to learn that John Calvin believed this. Calvin wrote:

“For what God has joined together, it is not lawful to put asunder,” so that, for those to whom he is Father the church may also be Mother. (Institutes 4.1.1)

Calvin’s high view of the Protestant (Reformed) Church, reflects his qualified view of the Ancient Church. (Calvin alternately praised and scorned the the early Church Fathers — depending on whether they were in agreement with him.) Cyprian of Carthage, a third century Church Father wrote:

He can no longer have God for his Father, who has not the Church for his mother. (On the Unity of the Church §6)

The implication here is that in dispensing with Christian life in the visible Church — whether Protestant, Roman Catholic, or Orthodox — Evangelicalism has become doubly estranged from its historic Christian roots: both in the Reformation and the early Church. As Evangelicalism, especially its Anabaptist variants, take on more extreme positions, it becomes a religion that neither the early Reformers nor the early Church Fathers would recognize as Christian.

Scripture and Creeds

One surprising finding is the positive regard Americans have towards creeds. There was a largely negative response, 58 percent, to the statement: “There is little value in studying or reciting historical Christian creeds and confessions.” This suggests an openness to using historic creeds or doctrinal statements to offset the emphasis on private interpretations of Scripture.

The next question then becomes which creed ought to be used? Each Protestant denomination has its own creed or confessions. For example, a Lutheran might tout the Augsburg Confession (1530), a Reformed Christian the Westminster Catechism (1646), and the Anglican the Thirty-Nine Articles (1563; see Note 1). For those interested in the early Church there are the Apostles Creed and the Nicene Creed.

Sola Scriptura?

The authority of Scripture cannot be understood apart from the interpretation of Scripture. It was found that half of the American population (51 percent) believes that “the Bible was written for each person to interpret as he or she chooses.” The Research Report (p. 14) noted that only 30 percent of Evangelicals agreed with this. That as many as a third of Evangelicals hold this view, (as opposed to half of the American public) while positive, should still be a matter of concern. Augustine of Hippo wrote:

If you believe what you like in the Gospel, and reject what you don’t like, it is not the Gospel you believe, but yourself.

Augustine here was warning against private interpretation of Scriputre. It is curious then that so many Protestants love this quote as IF Augustine agrees with their own doctrines and view or the gospel! This is simply not true. As a fourth-century Bishop of the Church, Augustine held firmly to an episcopal form of church government – the local church under the rule of the bishop. This is in sharp contrast to the presbyterian and congregational polity favored by modern Protestants. Augustine believed in authoritative Apostolic Tradition, the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist, baptismal regeneration, the sacrament penance, Mary’s perpetual virginity, the possibility of falling from grace, prayer to the saints and praying or the departed — all common practices of the ancient historic Church but which have been rejected and vilified by many of today’s Protestants and Evangelicals. See Joe Wilcoxson’s “Was St. Augustine a Protestant?” This narcissistic private reading of Augustine and the consequent distorted understanding of church history is tragic to say the least.

Much of the independent reading of Scripture can be traced to low-church Evangelicalism. As a remedy to this Matthew Block prescribes high-church Protestantism. Where popular Evangelicalism favors solo scriptura — reading the Bible independently of outside sources, historic Protestantism favors sola scriptura — reading Scripture with the creeds and in the larger Church (See Note 2). Mr. Block writes:

If we are going to address the rise of heresy in our churches, then Christians must rededicate themselves to reading the Bible in community—with the local church, yes, but also with the Church throughout history. If the Bible is truly the authority Evangelicals say it is, then we must also recognize that God has exercised that authority over Christians other than ourselves. The history of the Church, in its creeds and confessions, is a witness to other Christians who have been shaped by and wrestled with the Word of God. (Source)

However, Matthew Block fails to explain why Lutheranism, especially his brand of Lutheranism, offers the best remedy for the ills uncovered by the LifeWay survey. For all its affirming the authority of Scripture, Protestantism has historically suffered from fragmentation, in terms of doctrine, worship, and polity. Ultimately, Protestantism’s denominationalism is rooted in the private reading of Scripture implicit in sola scriptura. For example, one who joins a Lutheran church is following Martin Luther’s reading of Scripture. With the proliferation of mega-churches and many smaller community churches private interpretation of Scripture has become pervasive among Protestant churches today. Wheaton College Professor of Theology, Beth Felker Jones, attributes the doctrinal confusion to the rise of pastor-centered churches:

I fear that we’re spending too much time in cults of personality around charismatic superstar pastors, who often focus more on their personal theological idiosyncrasies and pet ideas than on basic Christian orthodoxy. (Source)

Much of Matthew Block’s prescription for the ills of Evangelicalism is sound but does not go far enough. He prescribes the classical Protestantism of the 1500s but an alternative is Ancient Christianity of the first millennium, e.g., the Seven Ecumenical Councils and the Church Fathers.

What the best of Protestant pastors must confess is this: Luther’s appeal to his own views can easily become the appeal of all sincere Protestants — who can appeal like Luther did to his own conscience and take his own stand even if it differs from Luther’s. Protestantism is full of little Luther’s taking their own stand for biblical truth giving rise to denominational differences that trouble Protestants who desire a visible unity for the Church.

Implications for the Future of Protestantism

The LifeWay survey poses significant challenges for Rev. Peter Leithart recent First Things article, “Is There a Future for Protestantism?” In this article Rev. Leithart approaches Protestantism doctrinally and sociologically. He asserts that as a sociological entity Protestantism does indeed have a future. He optimistically sketches a future where non-liturgical churches will adopt liturgies, non-sacramental churches will start having weekly Eucharist, and become more open to the rich heritage of historic ancient and medieval Christianity. The problem is that Rev. Leithart fails to present empirical evidence to support his claims. If anything, the evidence presented in the LifeWay survey and the analysis by Ligonier Ministries point to the spread of deviant doctrines and a growing disregard for church discipline and common worship on Sunday mornings. What we see here is more wishful thinking than facts-based realism.

Safe Harbor

Unlike Protestantism, which has been marked by denominational fragmentation, and even more disturbing, the inability to provide doctrinal and liturgical stability, Orthodoxy is marked by a stability that has endured for two millennia. Protestants tired of constantly changing doctrines might want to seek shelter in the Orthodox Church. The words of John Chrysostom, the fourth-century church father, still resonate today:

Just as a calm and sheltered harbour provides great security to the ships moored there, so does the temple of God: when people enter it, it snatches them away from worldly affairs as from a storm, and gives them the capacity to stand and listen to God’s words in calm and security.

This place [the Church] is the bedrock of virtue and the school of spiritual life…

You need only set foot on the threshold of a church and at once you are liberated from the cares of daily life. (Source)

More Reforms Needed?

It is regrettable that Rev. Leithart insists on rejecting Orthodoxy and its ancient patrimony of ancient liturgies, Church Fathers, Desert Fathers, Ecumenical Councils, and bishops who can trace their lineage back to the original Apostles. He calls for even more reforms for Protestant churches, but who knows where it will take them? Already much of what passes for “Protestant” churches today would be unrecognizable and abhorrent to the original Protestant Reformers. Those troubled by the predicaments and quandaries of Protestantism should heed the words of the prophet Jeremiah:

This is what the Lord says:

“Stand at the crossroads and look;

Ask for the ancient paths,

Ask where the good way is, and walk in it,

And you will find rest for your souls.”

(Jeremiah 6:16 NIV; emphasis added)

Robert Arakaki

Note 1: Some Anglicans might dispute that the Thirty Nine Articles are a creed, pointing out that Anglican rely on the Apostles Creed, the Nicene Creed, and Athanasian Creed. However, the fact that several sources refer to the Thirty Nine Articles as a “doctrinal statement” indicates that it delineates the distinctiveness of Anglican identity in a way that the three aforementioned creeds do not.

Note 2: Keith Mathison coined the phrase solo scriptura to highlight modern Evangelicalism’s divergence from historic Protestantism’s sola scriptura. See my review of Prof. Mathison’s The Shape of Sola Scriptura.

Articles

“Is There a Future for Protestantism?” by Rev. Peter Leithart. First Things 13 October 2016.

“Survey Finds Most Americans Are Actually Heretics” by G. Shane Morris. The Federalist 10 October 2016.

“Evangelicals, Heresy, and Scripture Alone” by Matthew Block. First Things, 4 October 2016.

“Evangelicals’ Favorite Heresies Revisited by Researchers.” by Caleb Lindgren. Christianity Today 28 September 2016.

“Americans Love God and the Bible, Are Fuzzy on the Details” by Bob Smietana. LifeWay-Research, 27 September 2016.

“An Orthodox Remedy for Evangelicalism’s Heresy Epidemic” by Robert Arakaki. OrthodoxBridge, 11 January 2015.

References

2016 State of American Theology Study – Research Report by LifeWay Research.

PowerPoint Presentation by LifeWay Research.

State of Theology: Key Findings by Ligonier Ministries.

Orthodox Resources

A Pocket History for Orthodox Christians by Father Aidan Keller.

An Online Orthodox Catechism by Bishop Alfeyev Hilarion.

Recent Comments