On 29 March 2011, Robin Phillips posted an intriguing and disturbing article, “Are Calvinists Also Among the Gnostics?” in which he discussed the tendency to Gnosticism in Reformed theology. More recently in December 2011, he posted, “A Critical Absence of the Divine: How a ‘Zero-Sum’ Theology Destroys Sacred Space” in which he discussed how this Gnostic tendency has impacted Reformed worship and church architecture.

This is not just Phillips’ own interpretation of Calvin and Reformed theology but a synopsis of an emerging discussion among scholars. He is careful to note that Calvin himself sought to maintain a dialectical balance between his spiritualizing tendency by putting a premium on secondary means. It was Calvin’s spiritual descendants (Jonathan Edwards, B.B. Warfield) who took this spiritualizing tendency further than he intended.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

The gnosticizing tendency is manifested in the minimizing or denial of secondary causation and the emphasis on divine immediacy. This is the notion that material means, e.g., sacraments, are irrelevant or interfere with the divine economy. Divine immediacy takes place by means of the Word of God. This has been extremely consequential for Reformed Christianity. It has resulted in the denial of sacred space, stained glass, gothic arches, crosses, altars, the church calendar. It explains the widely known iconoclasm of Reformed theology. It also accounts for Calvin’s aversion to annointing a sick person with oil for healing even though the practice is taught in Scripture. Reading this has helped me to understand why so many Reformed churches have a stark austere beauty. The purpose of Reformed architecture is to support the primacy of Scripture proclaimed in the sermon. This world view has ramifications for the rest of life, some of them quite surprising. It has led to Reformed pastors telling parents that all their good works as parents to raise believing children are of no lasting benefit.Robin Phillips’ argument is fairly complex. It is recommended that visitors go to Phillips’ site directly and read the posting directly. Below are excerpts from the two postings to assist the reader.

Excerpts from:

A Critical Absence of the Divine: How a ‘Zero-Sum’ Theology Destroys Sacred Space

The ancient Gnostics didn’t know about game theory, but they tended to treat God’s glory as if it was a zero-sum contest between God and creation. The glory of God, they seemed to think, could only be maintained by denigrating the created order, or at least denying that anything of spiritual value could be derived from the creation. In fact, the Gnostics adopted such a low view of the material world that they ended up denying that Christ even had a physical body. It would be beneath the dignity of the Divine Being, they thought, to have his glory mediated through material flesh.

In this article I will suggest that one of the temptations of the reformed theological tradition has been a tendency to operate with similar ‘zero-sum’ assumptions. What I am calling a ‘zero-sum’ approach (though the economic metaphor is only a metaphor and should not be pressed too closely) manifests itself in a number of ways, not least in the tendency to view the glory of God and the glory of creation as if they exist in an inverse relationship to each other, so that whatever is granted to the latter is that much less that is left over for the former.

In their polemics against the proliferation of images within Roman Catholic worship, both the English Puritans and the Continental Calvinists had a tendency to veer towards the type of disembodied Gnosticism that they would have discountenanced in any other context. The result has been to denigrate the created order and to create a false dichotomy between the spiritual and the physical.

I have sometimes heard extraordinary language is used to denounce the efficacy of good parental works from teachers who think that if our works can lead to godly offspring then we are depending on ourselves rather than God. Since godly parenting is ‘impossible’ and ‘beyond us’ and ‘outside our ability’ (all concepts that I have heard invoked) the solution is not to parent by works but by ‘faith.’

Are Calvinists Also Among the Gnostics?

Earlier in the year as I was reading history for my doctoral research with King’s College, London, I was struck again and again by just how Gnostic so much of the Calvinist tradition is, especially Calvinism of the Puritan variety.

The churches that followed in Calvin’s wake would be marked by this de-physicalising influence and the corollary tendency for the cerebral to swallow up the sacramental, for the invisible to absorb the incarnational.

The result of this disenchantment with liturgical approaches, together with the notion that worship was first and foremost a matter of instruction in the Word of God, dovetailed with the assumption among reformed communities (though not among those of the Lutheran and Anglican traditions) that for worship to be ‘spiritual’ it must be what they called ‘simple’ in the sense of being disencumbered with the trappings of materiality.

My Response

Overall, I agree with what Robin Phillips had to say. He raised issues that I had never thought of when I was a Reformed Christian. I think the concerns he raised are important and deserve to be addressed by other Protestants. In my comments below I do two things: (1) I point out areas where Phillips may have been too hard on Calvin, and (2) I raise implications of Phillips’ argument that he may have overlooked.

Where Phillips May Have Been Too Hard on Calvin

One missing element in Phillips’ analysis is Calvin’s emphasis on our mystical union with Christ and the importance of the Real Presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper for our life in Christ. These important themes have been suppressed or glossed over by certain of Calvin’s spiritual descendants. This is an element that the Mercersburg movement has sought to recover and reintroduce to the church with limited success.

Overlooked Implications of Phillips’ Argument

One missing element in Phillips’ postings is a discussion of the role of the pastor and the sermon in Christian worship. If one wishes to take the denial of secondary causation to its logical conclusion one would need to deny the need for sermon in which Scripture is explained and interpreted by the pastor. This mediation consists not just in the sermon on Sunday morning but also the pastor’s standing with the church at large. In the Reformed tradition the pastor occupies an office of the church; as part of the learned clergy he seeks to apply the best scholarship to his exposition of the text; and he seeks to speak the word to the situation of the flock under his care. Thus, the ordained minister serves several critical mediatorial functions in the life of the church. Without this understanding one becomes vulnerable to the direct ‘word of God’ given in certain Pentecostal circles.

Another missing element is the neglect of history as a consequence of gnosticism. Much of Reformed theology understands theology as consisting of timeless truths found in Scripture. The notion of a mediated faith tradition is either derided or subordinated to the divine revelation in Scripture. This tendency to ahistoricism gives rise to an uncritical acceptance of innovations of recent and a minimizing a solidarity with the historic church.

A possible implication that can be drawn from Phillips’ argument is that the Gnostic tendency in Protestant theology may account for the exuberant worship in Pentecostalism and the mega churches. Early Gnosticism had two opposite, seemingly contradictory manifestations: (1) the ascetic form that denigrated the body by eschewing food and sex, and (2) the libertine form that indulged the desires of the flesh in order to liberate the soul.

Possible Remedies

If Phillips is right in his diagnosis of a Gnostic tendency running through Reformed theology, what are the remedies available? There has emerged in recent years a reaction to the disembodied approach to the Christian faith.

The focus of this posting is to present a remedy for the ills described by Phillips. Below are some options available to those troubled by the Reformed tradition’s dualistic tendencies with my observations about the feasibility of the option presented. I will start of with the options that are closer to home for Reformed Christians before looking at more radical alternatives.

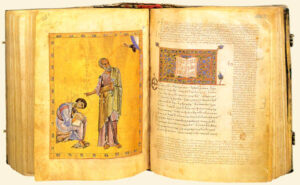

Mercersburg Theology. In recent years there has emerged in Reformed circles a renewed interest in Mercersburg Theology with its emphasis on the Eucharist, the church fathers, and church history. Among the proponents are Keith Mathison, Jonathan Bonomo, and W. Bradford Littlejohn. Keith Mathison’s Given For You attempts to make the Eucharist the focus of Sunday worship. The appeal of Mercersburg Theology lies in the fact that it is a form of high church Calvinism rooted in the theology of John Calvin and Continental Reformed theology. One can be “Catholic” and “Reformed” at the same time just by working with Reformed sources. The weakness of Mercersburg Theology is that it has had little impact on church life. I expect that the current interest in Mercersburg Theology will in time be forgotten. The ephemerality of Mercersburg Theology can be seen in its absence in the United Church of Christ, the one denomination with direct ties to Mercersburg Theology.

Ancient-Future Worship and the Convergence Movement. Examples of the ancient-future worship can be found in Thomas Oden and Robert Webber. They have advocated a return to a more historically grounded and liturgically approach to worship and theology. While Oden remained a Methodist, Webber left his Baptist roots to become an Episcopalian. The ancient-future movement is diverse in composition and eclectic in its method. This eclecticism can be seen in the fact that rather than affiliate with one of the historic traditions, many ancient-future evangelicals on their own initiative appropriate elements from outside traditions. The best example of the convergence movement is the Charismatic Episcopal Church which seeks the blending or convergence of three steams: Evangelicalism, historic Anglicanism, and the charismatic renewal. For a conservative Reformed Christian the challenge here is the postmodern eclecticism and a free wheeling independence unchecked by historic tradition.

Ancient-Future Worship and the Convergence Movement. Examples of the ancient-future worship can be found in Thomas Oden and Robert Webber. They have advocated a return to a more historically grounded and liturgically approach to worship and theology. While Oden remained a Methodist, Webber left his Baptist roots to become an Episcopalian. The ancient-future movement is diverse in composition and eclectic in its method. This eclecticism can be seen in the fact that rather than affiliate with one of the historic traditions, many ancient-future evangelicals on their own initiative appropriate elements from outside traditions. The best example of the convergence movement is the Charismatic Episcopal Church which seeks the blending or convergence of three steams: Evangelicalism, historic Anglicanism, and the charismatic renewal. For a conservative Reformed Christian the challenge here is the postmodern eclecticism and a free wheeling independence unchecked by historic tradition.

Anglicanism. A number of Protestants and Evangelicals see in Anglicanism an appealing mixture of liturgical worship, historic tradition, and ordered church life. Unlike the previous option, the Anglican option is more solidly rooted in a defined historic tradition and has a canon of theological writings: Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Richard Hooker and William Laud. The Anglican tradition possesses a certain stability with its tradition of using a normative prayer book for its worship life. While the Anglican tradition allows for a more embodied approach to worship and church life, it is currently in a state of disarray as a result of the current apostasy in the Episcopal Church.

Roman Catholicism. A number of Protestants, even Reformed Christians, have abandoned Protestantism and “crossed the Tiber River.” While the Roman Catholic Church is an embodied form of Christianity, becoming Roman Catholic would be a drastic cure for those seeking a remedy for Calvinism’s gnostic tendencies. One major issue for a Reformed Christian is the jettisoning of sola scriptura for the infallibility of the Papacy. While Roman Catholicism does take an embodied approach to faith, its organizational life seem to be heavily influenced by a bureaucratic and legalistic ethos. A Reformed Christian thinking of becoming Roman Catholic would do well to take a good hard look at the Great Schism of 1054 and ask if Rome did the right thing in breaking away from the other historic patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

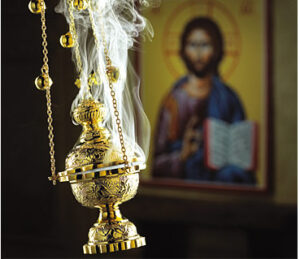

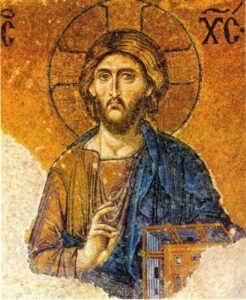

Eastern Orthodoxy. Long ignored and overlooked by Protestants, one of the biggest surprise in recent years is Orthodoxy’s rapid growth as growing numbers convert to Orthodoxy. Long regarded as an ethnic denomination, Orthodoxy is in the process of becoming an American church. The appeal of Orthodoxy lies in its historical rootedness and its mystical/organic approach to worship and church life. Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the Incarnation of Christ and its implication for all of life present a deep cure for any gnostic tendency one may have. Becoming Orthodox will not be easy for a Reformed Christian, it will require giving up the Scripture over Tradition paradigm that underlies sola scriptura for Scripture in Tradition paradigm.

Finding the Right Remedy

These are confusing times. There are many spiritual pitfalls for unwary Christians. Robin Phillips relates that he and his family were at one time members of a crypto-Gnostic group. They found spiritual growth and healing in the liturgical life of an Anglican parish. Soon after, they affiliated themselves with a Reformed church where they heard fierce denunciations of icons and liturgical symbolism by James Jordan. In another posting, “Aids or Idols? The Place of Images in Worship” (posted 3 October 2010) Phillips presents a reasoned and Scriptural defense of the use of icons in Christian worship. I suspect that the Anglican via media which enabled him to take an inclusive and reasonable approach to the use of icons was broad enough to allow him to become a Calvinist. Phillips closes this posting with a question for his readers to ponder.

Further, if our practice implies that colors, symbols, gestures, smells and three-dimensional objects are inappropriate for the house of the Lord and must be reserved for “secular” occasions like birthdays, parades, weddings and Christmas banquets, then are we not driving a wedge between the deepest human yearnings and the God who made them? Are we not reinforcing the myth that Christian truth should be kept unbodied – a myth that has had enormous implications for how modern evangelicals understand the meaning of “kingdom of God” and has virtually eliminated any concept of Christendom from contemporary Protestant consciousness?

If Gnosticism’s toxic influence can be discerned in Reformed theology, what is the appropriate remedy? What remedy does Robin Phillips propose? I appreciate his reasonable and open minded approach to the issues, but how do we stop the dread disease of Gnosticism? He seems to be advocating via media, but is the Anglican via media sufficient to defeat this pernicious spiritual disease? Or do we need stronger medicine along the lines of Orthodoxy?

Gnosticism is dangerous spiritually because it makes the individual believer independent of the Church and divorces faith from action. The best cure for a religious tradition weakened by implicit gnosticism is not a system of doctrine that denounces the gnostic heresy but rather an orthodox faith embodied in a Christian community. An embodied faith community will be marked by a common Eucharistic worship, a shared universal confession of faith, and a leadership that follow the teachings of the apostles. Irenaeus of Lyons in his classic apologia against Gnosticism: Adversus Haereses (Against Heresies) put forward two identifying for the true Christian Church: catholicity and apostolicity.

The Orthodox Church offers strong protection against Gnosticism through its holistic understanding of Christianity as the Tradition of Christ lived out by the Church, the body of Christ. Orthodoxy’s strongest defense against Gnosticism lies not in the Liturgy, icons, holy days, priests wearing vestments, creeds, and prayer books but in Holy Tradition. A church can have all the listed items and not be a capital “O” Orthodox Church. Orthodoxy is relational; one is linked to the Church Catholic through the Eucharist and one is linked to the Apostles through apostolic succession via the bishop. The theological method of Orthodoxy is the reception of Apostolic Tradition, not the negotiation of competing extremes, e.g., low church Evangelicalism versus high church Anglo-Catholicism. The classic form of sola scriptura combined with the regulative principle is quite compatible with the rich liturgical and aesthetic traditions of Anglicanism and Lutheranism. But even then there is fundamental divide between them and Orthodoxy — Holy Tradition. So long as one holds to sola scriptura one cannot be an Orthodox Christian, one remains a Protestant. Sola Scriptura because it denies the binding authority of Tradition is vulnerable to being reinterpreted and renegotiated opening the way for doctrinal innovation or doctrinal drift. Becoming Orthodox is indeed strong medicine but let us keep in mind Ignatius of Antioch’s teaching that the Eucharist is the “medicine of immortality” received from the bishop, the true successor to the apostles:

…so that you obey the bishop and the presbytery with an undisturbed mind, breaking one bread, which is the medicine of immortality, the antidote that we should not die, but live for ever in Jesus Christ (Ignatius of Antioch, Letters to the Ephesians 20:2).

Robert Arakaki

See also:

Robin Phillips – “8 Gnostic Myths You May Have Imbibed”

Robert Arakaki – Irenaeus of Lyons: Contending for the Faith Once Delivered

Recent Comments