Pastor Andrew Sandlin recently posted a beautiful and poignant blog posting “Time Passages” about the trials of an aging church leader. He wrote:

It is arresting to observe the constancy of older men and women within the variability of historical flux and the inevitable change it engenders. The world has changed, but they have not. They seem an anachronism to their juniors, for whom the unquestioned assumptions of the present age are normative. The elders carry with them the perspectives, virtues, convictions, prejudices, and vices of the peculiar era of their youth. To their idealistic juniors, the prejudices and vices predominate, and the virtues and convictions evaporate at the scrutiny of youthful eyes naively conditioned by a single era, their own era, whose normativeness they would not think to question. (Emphasis added)

The reflection is by a church elder concerned about the handing over of church leadership to the next generation. He fears that the hard earned wisdom of his generation will be dismissed out of hand by their successors.

The passage of time is hitting baby boomer Evangelicals hard. As they head into the 50s and 60s their perspective on life changes. The sunny optimism of youth is being overtaken by troubling shadows of old age. The forever young baby boomers find themselves being confronted by end of life issues like retirement, physical decline, and inevitable death.

The local church once thought to be a place of solace and security has become a source of uncertainty and anxiety. Michelle Van Loon in “Aged Out of Church” described how the mid life crisis is affecting Evangelical churches.

Church should be a place of meaningful connection with God and others at every stage of our lives, but nearly half of more than 450 people who participated in an informal and completely unscientific survey I hosted on my blog last year told me that their local church had in some painful ways exacerbated the challenges they faced at midlife. As a result, they’d downshifted their involvement in the local church from what it had been a decade ago.

Pastor Sandlin is calling for an intergenerational conversation in the church. He wants the younger generation to be receptive to the “strangeness” of the past.

What in the 1960’s was termed the “generation gap” is, however, precisely the opposite of what should occur. A conversation, not a gap, is what is most needed. A generational conversation is essential not only to transmit the best elements of the past’s “strangeness” to a succeeding generation but also to exhibit the subversive fact of historical conditioning to the previous one, which ordinarily glories in the peculiar features of the age of its youth, and intensely so the older it grows. (Emphasis added)

Pastor Sandlin has a good point here. There is indeed a need for intergenerational conversation. The wisdom of the Fathers is desperately needed, especially by cultures like ours which have been given over to the youth. However, there are powerful forces in Evangelicalism that work against this. Even the best and most mature Evangelical churches place a premium upon youthfulness and the innovation that goes with it. Michelle Van Loon observed:

When we in the church ape (awkwardly!) our culture’s obsession with all things young and cool, when we focus our energies on creating ministries targeted at the same desirable demographic groups targeted by savvy advertisers, we communicate to those who don’t fit those specs that they are less desirable to us than the ones we really want in our church family.

The emphasis on evangelism has led to the drive to boost church membership, draw in young families, and keep up with modern youth culture. As a result of this, many ministry programs in Evangelicalism have been geared to the first half of life issues: how to find God’s will for finding a good job and the perfect mate, how to have a solid spiritual life while living life to the fullest, how to raise a godly family, how to have a Christian witness at work and with friends. Little is said from the pulpit about second half of life issues.

From Generation to Generation

Pastor Sandlin’s lament is in many ways that of a Protestant without an enduring tradition. There is no capital “T” Tradition in Protestantism, only small personal traditions. He wrote:

The solidarity of humanity is marked partly by this gripping trait – the ability not merely to span eras (“tradition”) but to commit a small portion of one’s past, one’s private, unrepeatable tradition, to another individual. (Emphasis added.)

These small traditions are fine in the short run but are incapable of sustaining a congregation for the long haul, i.e., over the centuries. That is why Protestantism is in such dire straits today.

The abandonment of Tradition has made the Evangelical culture vulnerable to the flux of modernity. For Evangelicalism the Gospel is eternal but the forms of church structure and the framework for worship and discipleship are temporary and contingent, changing from one generation to the next – often every few months if not every week! Like their Roman Catholic elder brothers Evangelicals never quite escaped theological innovation. This disregard/dismissal of Tradition has resulted in one generation feeling little obligation much less a sacred duty to learn from their predecessors about the Christian way of life.

This historical flux lamented here by Pastor Sandlin can be traced to the Protestant principle: “Ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda” (the church reformed, but ever reforming). The Protestant Reformers did not want change for change sake; rather they sought change on the basis of Scripture. But without a Tradition that acts as a guardian to how Scripture is to be read and interpreted, the Reformers opened the floodgates for innovation.

Over the past several centuries Protestantism has undergone tremendous changes, but in recent years the pace of change accelerated. Protestantism’s landscape has changed such that familiar landmarks are disappearing or becoming barely recognizable to the older generation. Evangelical theology has recently branched off into neo-Calvinism, neo-Pentecostalism, and postmodern Emergent theology. This loss of historical memory can be seen in the recent shift away from “traditional” hymns to contemporary worship with praise bands using electric guitars and drums. The irony here is that the so called “traditional” hymns for the most part date back to the 1600-1800s!

The Comfort and Security of Holy Tradition

So, what is missing? What is missing from the best of Evangelicalism is a deeply rooted and sacred commitment to Holy Tradition. Tradition consists of one generation passing on and another generation receiving a body of teaching. The Apostle Paul expected the early Christians to be committed to Tradition. He admonished the Christians in Thessalonica:

So then, brethren, stand fast and hold the traditions which you were taught, whether by word or our epistle. (2 Thessalonians 2:15; OSB; emphasis added)

Here Paul instructs the Christians to hold fast to both written Tradition (Scripture) and to oral Tradition. This concern with the traditioning process did not begin with Paul. Tradition did not as it were fall unexpectedly from the sky into the lap of the early Church. No, Holy Tradition has a deep historicity that reaches back into the Tradition of the Old Testament saints and patriarchs.

What we have heard and known,

What our fathers have told us.

We will not hide them from their children;

We will tell the next generation . . . .

. . . which he commanded our forefathers

to teach their children,

so the next generation would know them,

even the children yet to be born,

and they in turn would tell their children.

(Psalm 78:3-6; NIV; emphasis added)

This sense of obligation to the past is deeply engrained in Orthodoxy. Metropolitan Kallistos Ware in The Orthodox Church (ch. 10) captured wonderfully this deep sense of reverence the Orthodox have for the past.

When Orthodox are asked at contemporary inter-Church gatherings to sum up what they see as the distinctive characteristic of their Church, they often point precisely to its changelessness, its determination to remain loyal to the past, its sense of living continuity with the Church of ancient times. (Ware pp. 195-196; emphasis added)

So, what is Holy Tradition? Ware describes it in this way:

A tradition is commonly understood to signify an opinion, belief or custom handed down from ancestors to posterity. Christian Tradition, in this case, is the faith and practice which Jesus Christ imparted to the Apostles, and which since the Apostles’ time has been handed down from generation to generation in the Church. But to an Orthodox Christian, Tradition means something more concrete and specific than this. It means the books of the Bible; it means the Creed; it means the decrees of the Ecumenical Councils and the writing of the Fathers; it means the Canons, the Service Books, the Holy Icons – in fact, the whole system of doctrine, Church government, worship, spirituality and art which Orthodoxy has articulated over the ages. Orthodox Christians of today see themselves as heirs and guardians to a rich inheritance received from the past, and they believe that it is their duty to transmit this inheritance unimpaired to the future. (p. 196, emphasis added)

In contrast to Sandlin’s aging church elder who has only personal insights to pass on to the next generation in Orthodoxy there is a sense that one is part of a Great Tradition that spans the generations and extends to the Second Coming.

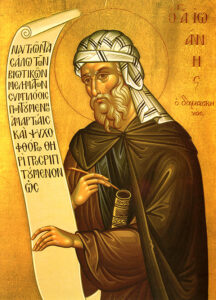

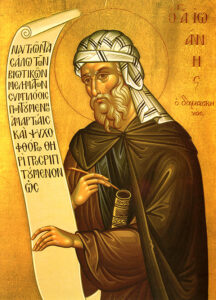

John of Damascus

This reverence for Tradition goes back to early church fathers like John of Damascus who wrote:

We do not change the everlasting boundaries which our fathers have set but we keep the Tradition, just as we received it. (in Ware p. 196; emphasis added)

John of Damascus here is echoing the Prophet Jeremiah:

Stand at the crossroads and look;

ask for the ancient paths,

ask where the good way is,

and walk in it,

And you will find rest for your souls.

(Jeremiah 6:16, NIV; emphasis added)

If the traditioning process is part of both the Old and the New Testaments, one has to wonder — and lament with them — why there is so little of it among Evangelicals.

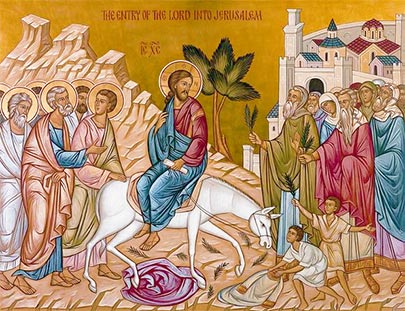

Unto the Ages of Ages

The stability of Holy Tradition makes intergenerational conversation a natural and expected process. The solidarity of Orthodoxy lies in Holy Tradition. The Liturgy will be there for generations to come. The liturgical calendar and the ascetic disciplines will likewise be followed by future generations. A longtime Orthodox can share insights to younger Orthodox about keeping the fast, following a rule of prayer, how to participate in the Liturgy, and the significance of the Pascha (Easter) service. They can talk about the lives of the saints and martyrs, or the writings of the church fathers.

As the years go by one becomes familiar with the prayers and the theme for the services; one’s heart and mind are reshaped through repeated exposure to the prayers and hymns of the Church. Spiritual healing takes place and enlightenment of the soul commences. In Orthodoxy the past is not “strange” but familiar because it is rooted in the Great Tradition. These things are even more true when there are Orthodox parents and godparents who faithfully live out the teachings of the Church. Where Pastor Sandlin’s church elder can only hope to pass on a private unrepeatable tradition, the Orthodox Christian passes on a Tradition held by the entire Church.

In the Liturgy are prayers that can be helpful for dealing with the second half of life issues. These two petitions are found in the Completion Litany just before the Nicene Creed.

That we may live out our lives in peace and repentance, let us ask of the Lord.

A Christian end to our lives, peaceful, free of shame and suffering, and for a good defense before the judgment seat of Christ, let us ask.

Here we ask God for his mercies in order that we may be faithful to the Gospel all our life. We seek to live a life of prayer and repentance in preparation for that great day when we will stand before the judgment seat of Christ (Matthew 7:21-23, Romans 2:6-11). The Good News is not just the forgiveness of our sins, but also our being transformed into the likeness of Christ. This is the doctrine of theosis (deification). As we stand during the Liturgy we see the icons of the saints who have gone before us. We are reminded that one day our earthly life will come to a close and we will then become part of the great cloud of witnesses mentioned in Hebrews 12:1. Eventually, the intergenerational conversation will take us to the communion of saints and to the life of the age to come where we will come face to face with Christ.

Radiant Pascha!

The Ancient Beauty

Too late have I loved you, O Beauty so ancient and so new, too late have I loved you!

(Confessions 10.27)

Here Augustine talks about his encounter with God; this line will also resonate for many converts who have been seeking something more in worship. There is a mystical beauty about Orthodox worship that makes even Protestant “traditional worship” ring a bit hollow and the notion of “contemporary worship” ludicrous. The Liturgy is for the ages. The discovery of the Liturgy leads many converts to wish they had known of the Liturgy sooner.

It is old, very old. So old that almost I feel young again . . . .

The line above is from the Lord of the Ring where Legolas the Elf commented on Fangorn Forest. In the Orthodox Liturgy there is the sense of being part of an ancient tradition that goes on and on and never grows old. Becoming Orthodox involves more than acquiring a new theology, one joins a church rooted in antiquity. Ware wrote:

The thing that first strikes a stranger on encountering Orthodoxy is usually its air of antiquity, its apparent changelessness. Orthodox still baptise by threefold immersion, as in the primitive Church; they still bring babies and small children to receive Holy Communion; in the Liturgy the deacon still cries out: ‘The Doors! The Doors!’ – recalling the early days when the church’s entrance was jealously guarded and none but members of the Christian family could attend the family worship; the Creed is still recited without any additions. (p. 195; emphasis added)

I have experienced the Orthodox Church’s antiquity in surprising ways. One is the recent visit of the Kursk Root Icon to Hawaii. This particular icon dates back to the 1200s. I was amazed to see something that is five centuries older than the United States of America and which predates the Protestant Reformation by three centuries! One cannot help but feel like a child in the presence of this ancient heritage. It is indeed a heritage, a Holy Tradition worthy of reverence and our sacred duty to pass on to our “children’s children” with confidence as we depart this world for the ages to come. May God have mercy on us all.

Robert Arakaki

Sources

P. Andrew Sandlin. “Time Passages” in docsandlin.com (3 April 2014)

Michelle Van Loon. “Aged out of Church” Christianity Today (5 April 2014)

Timothy (Kallistos) Ware. The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books. 1963.

Augustine. Confessions. (Translation by John K. Ryan) Penguin Books.

Recent Comments