For years Orthodoxy was invisible on the American religious landscape. Few people paid attention as they drove past Orthodox churches with exotic ethnic names on their way to the more familiar Protestant or Roman Catholic churches services. Odds are high that Orthodoxy was not on your radar screen. However, that has changed. Over the past several decades, American Christianity has undergone massive changes. The implosion of liberal mainline Protestantism, the introduction of the Novus Ordo Mass in Roman Catholicism, the shift to contemporary worship among Evangelicals, post-Evangelicalism, the YRR (Young, Restless, and Reformed) movement, and the growing numbers of Nones (not religious) and Dones (formerly religious) have rendered America’s religious landscape unrecognizable to those familiar with the America of the 1950s and 1960s.

These developments gave rise to a small but growing trend: Protestants and Evangelicals searching for the early Church, the historic Faith, and hungering for a more reverent liturgical worship. Many eventually converted to Orthodoxy. While small, this trend has been ongoing and steadily growing. The fact that Protestants and Evangelicals—many pastors, elders, lay leaders—have been converting to Orthodoxy caught the attention of church leader leading them to investigate Orthodoxy and formulate ways of responding.

A reader brought to my attention a 2017 committee report presented to the URCNA (United Reformed Churches in North America). The URCNA broke off in the 1990s from the CRCNA (Christian Reformed Churches in North America), which traces its roots back to Belgium and the Netherlands. The committee was chaired by the Rev. Adam Kaloostian of the SWUS classis of the URCNA. What struck me as I read the report was how seriously they were taking Orthodoxy. I did not always agree with the way they presented Orthodoxy, but I appreciated the way they treated the Orthodox Church with respect. Orthodoxy in America is no longer invisible but is now on the Reformed churches radar screen. Reformed churches are beginning to take notice of Orthodoxy in America and wondering what to make of it. [See the Report.]

Using the Radar for Detection and Identification

The radar was used during World War II for the purpose of detecting enemy aircraft or ships at a distance. At the time it was a brand new technology. While its scientific and technological basis can be traced back to the late 1800s, it was not until the 1930s that countries began to work in earnest in refining the technology to gain an advantage militarily. In the case of the Pearl Harbor attack, there was an early warning radar stationed on the North Shore of the island of Oahu. In the early hours of 7 December 1941, the two operators saw a large number of approaching aircraft. They called Fort Shafter with this worrisome information. The officer who received the report dismissed it, and the rest—as they say—is history.

The radar was used during World War II for the purpose of detecting enemy aircraft or ships at a distance. At the time it was a brand new technology. While its scientific and technological basis can be traced back to the late 1800s, it was not until the 1930s that countries began to work in earnest in refining the technology to gain an advantage militarily. In the case of the Pearl Harbor attack, there was an early warning radar stationed on the North Shore of the island of Oahu. In the early hours of 7 December 1941, the two operators saw a large number of approaching aircraft. They called Fort Shafter with this worrisome information. The officer who received the report dismissed it, and the rest—as they say—is history.

The URCNA report can be considered an early warning to Reformed church leaders of a new religious phenomenon heading their way. It appears that ancient Christianity brought over by immigrants may finally be extending beyond its ethnic confines and drawing in people from the mainstream of American Protestantism and Evangelicalism. In addition to using the radar for detecting incoming objects, the military also needed a means for identifying friendly and hostile forces. This led to the creation of IFF (Identification, Friend or Foe). The URCNA report on Orthodoxy is like the military radar seeking to identify incoming objects as friend or foe. Hence, the Report’s seeking to evaluate Orthodoxy.

Using the Radar for Navigation

In addition to detection, the radar can also be used for navigation. In the case of navigation the radar is positioned on a moving vessel and the vessel is moving towards a desired destination. Radar technology has advanced considerably since its early days. Range measurement—in the form of concentric rings—makes it possible to estimate how far away detected objects are. Gain control can be adjusted to enable the operator to detect remote objects and/or sea clutter or rain. Parallel index lines can help the ship’s captain assess the distance at which the ship will pass a fixed object on a particular course. Vector mode, past position, and mark are all useful means for navigating one’s way through a busy and confusing waterway. However advanced the radar technology may be, it won’t be of much help unless one also has in hand a good map.

In the same way, Christians trying to make their way through the confusing and turbulent waters of modern day post-Christian society are in need of good navigation tools and accurate maps if they wish to find safe harbor. Many confused Evangelicals and Protestants feel adrift, caught up in a huge theological storm in which their boat (church) is taking on water. They may not know it but safe harbor can be found in historic Orthodoxy.

Church history can serve as a map for Evangelicals and Protestants troubled by the present situation. I once told a bible college student doing a research project on why local Hawaii Evangelicals were converting to Orthodoxy: “If you don’t know where you’re from, you won’t know where you’re going.” By that I meant by knowing church history, you will be in a better position to discern whether what your church believes and practices is in line with historic Christianity or a deviant heresy.

An Assessment of the URCNA Report

The primary intent of this article is not to refute the URCNA report (Report) but rather to make a few points for inquirers to consider and to stimulate further conversation between Reformed and Orthodox Christians. The Report has four sections: (1) Mystery, (2) History, (3) Beauty, and (4) Experience. There is one more section that discusses how Reformed churches should deal with members curious about Orthodoxy. One strength of the Report is the ample citations from Orthodox sources. One does not find vague generalizations or bizarre caricatures but a quite accurate depiction of the Orthodox point of view. Another strength is the awareness that Orthodoxy is not the same as Roman Catholicism (see page 22).

The “Bibliography / Suggested Resources” listed towards the bottom of the Report is quite good. It’s balanced and quite comprehensive. If there is a glaring omission to the list, it would be the absence of the 1672 “Confession of Dositheus,” which comprises Orthodoxy’s formal position on the Reformed tradition. I have a few additions for the book list: Jaroslav Pelikan’s five-volume The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, JND Kelly’s Early Christian Doctrines, Alister McGrath’s Iustitia Dei: A History of the Christian Doctrine of Justification, and Gustaf Aulen’s Christus Victor. I recommend these works because they will provide the inquirer with the historical context for understanding Orthodoxy and the Reformed tradition.

Section 1 – Mystery

The Report did a good job of describing Orthodoxy’s understanding of God as Mystery. The writers of the Report are to be commended for their humility in admitting that they—the Reformed community—could do a better job of embodying the mystery of God’s love. They noted that people with emotional wounds and scars will desire something more than abstract ideas about God. They recommended that Reformed churches spend more time in practical fellowship—weeping with those who weep, rejoicing with those who rejoice—in order to enable those who are hungering for something more to experience the “mysteries of the Christian life” (p. 6). However, it should be noted that it is not just the emotionally wounded Calvinists who are drawn to Orthodoxy. Among the converts to Orthodoxy are often pastors, elders, and seminarians who have experienced the best the Reformed world has to offer.

What sets Orthodoxy apart from Calvinism is not so much apophatic theology, but how Orthodox theology is deeply grounded in worship and prayer. There is an ancient Christian saying: “If you are a theologian, you will pray truly. And if you pray truly, you are a theologian.” It is through prayer that we come to know God. While Calvinists do take prayer seriously, prayer seems to be detached from Reformed doctrine. The Reformed tradition abounds with theologians who wrote books on theology and the Bible, but where are the Reformed mystics, holy men, or saints? It was perhaps in reaction to the abuses in medieval Roman Catholicism that led to a spiritual egalitarianism that had little or no place for such radical transformation of lives. This neglect of the mystical dimension of worship for rational theology has caused many Reformed Christians to be drawn to the mystical depths of Orthodoxy and her Liturgy.

The Report concluded the first section with a call for “a robust and consistent Reformed piety [that] is saturated by delight in the mysteries of God.” This is very commendable but it should be noted that this particular paragraph says nothing about the mystery of the Eucharist. This oversight contributes to the hunger for mystery that is drawing many Reformed Christians to Orthodoxy. It is a sad fact that in the majority of Reformed churches the Lord’s Supper is celebrated only occasionally. Moreover, the early Christians believed in the real presence of Christ’s Body and Blood in the Eucharist. Yet in many Reformed churches today the mystery of the Eucharist has been replaced with a symbolic understanding. The debate between Princeton’s Charles Hodge and Mercersburg’s John Williamson Nevin and Philip Schaff in the mid-1800s over the Eucharist shows how far Reformed churches in America have drifted, not just from the early Church, but also from John Calvin as well. Many would be shocked to learn that Calvin held that thinking of the Lord’s Supper as “naked and bare signs” an “error not to be tolerated in the Church” (“Confession of Faith concerning the Eucharist” in Reid p. 169).

Section 2 – History

Another reason why Reformed Christians are turning to Orthodoxy is the hunger for the early Church. The Report’s response is twofold: (1) to challenge Orthodoxy’s claim to unbroken historical continuity and (2) to show that Reformed churches have a historical continuity that is just as valid as Orthodoxy.

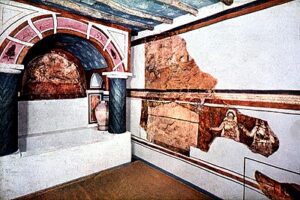

The Report pointed to icons as proof against Orthodoxy’s claim to unbroken historical continuity (p. 13 ff.). This is not surprising as icons represent the most visible point of difference between Orthodoxy and Calvinism. The controversy over icons is far from simple. The differences go beyond aesthetics to doctrine, authority, and practice. For the sake of brevity, I will note two weaknesses in the Report: (1) the Report failed to take into account the images found in the Christian church in Dura Europos dated by archaeologists back to 250 and (2) there is no attempt by the Report to reconcile the apparent contradiction between the Second Commandment in Exodus 20 and the making of images in Exodus 26. The presence of images in the Tabernacle described in Exodus, Solomon’s Temple, and in the early church in Dura Europa and the Roman catacombs all point to the acceptance of images in Jewish and Christian worship. If the Reformed tradition wishes to argue that icons in churches is an innovation, they will need to present evidence showing when this innovation emerged, who introduced this novel practice, and how this resulted in a radical departure from ancient Christian worship.

It must be kept in mind that Orthodox Tradition is dynamic, not static. The continuity in Tradition is much like a little mango seedling growing into a huge fruit-bearing mango tree. What we see here is development and growth, not evolutionary mutation from one species into another. Reformed inquirers need to keep in mind that church history is a complicated and messy affair. It is not straightforward and simple. If Christian theology was static, we would not have theological terms like “Trinity,” “Incarnation,” and Christ having “two nature.” More will be said about this in my discussion about Robert Godfrey’s historical critique of the iconoclasm controversy. My advice for Reformed inquirers is that as they compare the beliefs and practices of the early Church against Reformed and Orthodox churches today and determine which of the two most closely resemble the early Church.

Section 3 – Beauty

The report did a commendable job on the appeal of the beauty in Orthodox worship. They responded by noting that there is beauty as well in the Reformed emphasis on simplicity in worship:

Since a hallmark of Reformed churches since the Reformation has been simplicity of worship and since Reformed church décor is often designed to minimize distraction from the preached word, converts like the one just cited describe their transition as one from worship that is ugly and bland to worship that is beautiful and vibrant (p. 19).

The question that needs to be asked with respect to the Reformed emphasis on simplicity in worship is: “Where does the Bible teach simplicity in worship?” This emphasis on simplicity is not grounded in Scripture but more in the Reformers’ emotional reaction to medieval Catholicism and to the overzealous Puritans who went even further than the original Reformers.

While granting that the aesthetics of Orthodox worship does appeal to many people, the Report makes two criticisms of Orthodox worship. First, they make the claim that that the aesthetics of Orthodox worship is not so much rooted in heavenly worship but rather represents “a particular version of artistic expression . . . of the Byzantine Empire” (p. 23; italics in original). Second, they assert that the sensuous beauty of Orthodox worship fails to provide true beauty in the apparent outward ugliness of the Cross (p. 24). Note here the Report’s apparent assumption—that early Christian worship emerged out of a radical break from Old Testament Jewish worship and drew its inspiration from Greco-Roman paganism. The problem with this position is that it completely ignores what the Old Testament Scriptures had to say about worship. And more significantly, it ignores the divine injunction that the Old Testament place of worship be constructed according to pattern shown Moses on Mount Sinai (Exodus 25:40, 26:30). Old Testament worship is based on divine revelation. Early Christian worship sought to retain the received tradition of worship divinely given by God to Moses, not in emotional reactions to some prior tradition.

The Report notes that the Reformers in Geneva sought a liturgy “according to the custom of the ancient church.” (p. 16) However, it should be kept in mind that they were attempting to recover a lost tradition by relying on the tools of humanist scholarship, studying the ancient texts then applying the results of their study to their churches. The sad fact of the matter is that this methodology is at best unstable and shifting as can be seen in the prevalence of the symbolic understanding of the Lord’s Supper and the widespread acceptance of contemporary praise music by Reformed churches.

Ironically for all their insistence on biblical worship, the Reformed tradition overlooked the role of Tradition in worship. The Apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 11:23 reminded the Corinthian Christians that the Eucharist was traditioned (delivered) to them from Paul who received the Eucharist from Christ himself: “For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread . . . .” For the early Christians, the Eucharist did not come from the exegesis of the New Testament text but rather from a received Tradition that went back to the Apostles who were taught by Christ. There is evidence that the early Christian understood the Eucharist as part of Tradition. An examination of the letters of Ignatius of Antioch (d. 98/117), e.g., Letter to the Smyrnaeans, showed that the early Christians believed in the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist and the importance of the bishop presiding over the Liturgy. The Reformed tradition on the other hand started from scratch in the 1500s and came up with a version of the Lord’s Supper that diverged from the early Church.

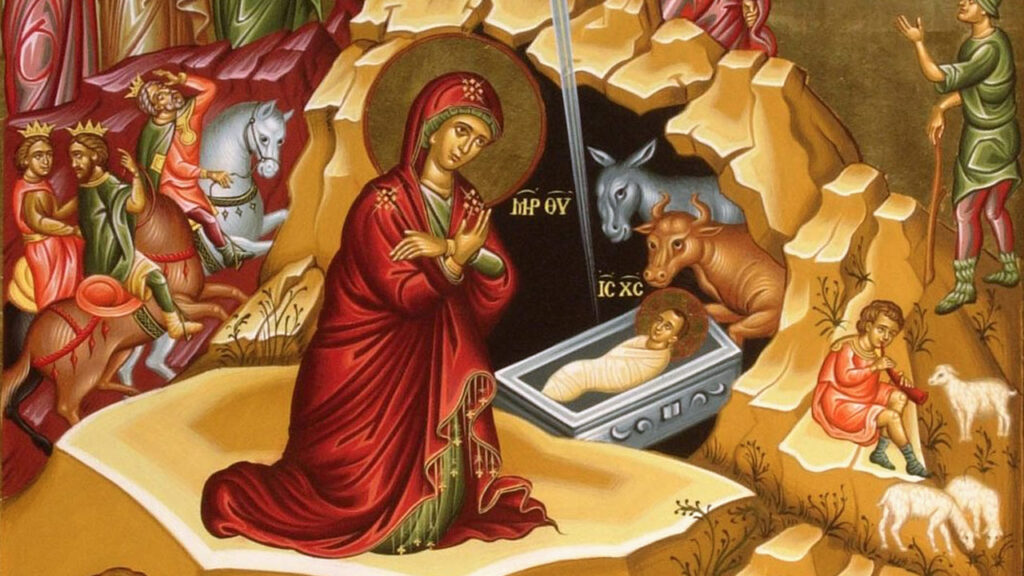

While appreciative of the link between beauty and eschatology in Orthodox worship, the Report criticizes Orthodoxy for what it sees as a tendency to an “over-realized eschatology” (p. 20). This is an interesting criticism. I would be interested in learning on what basis an eschatology can be considered over-realized. I suspect that behind this criticism is an implicit secular worldview in Reformed theology that detaches Sunday worship from the eternal heavenly worship and reduces Sunday worship to verbal proclamation of that which the listeners will not partake of until the Second Coming of Christ. My response is that Reformed theology underestimates the radical implications of the Incarnation. The Incarnation provides the basis for Orthodoxy’s sacramental approach to material creation. The eternal Word has entered the cosmos turning mere creation into sacraments of the kingdom of God. Because of the Incarnation mere humans become vessels of the Holy Spirit, fallen sinners are transformed into creatures of glory, the “ordinary” Sunday Liturgy becomes an extension of the heavenly worship, in the sacrament of confession we come before Christ the Judge of all humanity, the bread and wine offered in the Eucharist become the body and blood of Christ, and wood and paint become icons—windows to heaven. In the Reformed secular framework, the kingdom of God remains at a distance, but for the Orthodox the kingdom of God has arrived. This is realized eschatology.

Section 4 – Experience

This section opens with testimonies by former Calvinists who found in Orthodox worship a beauty and spiritual fulfillment that they did not experience in the Reformed tradition. I am in agreement with the Report’s assessment that happy spiritual experiences are not sufficient in themselves. Beauty in worship must be grounded in truth, in faithful worship of the one true God.

I was pleasantly surprised by the Report’s endorsement of the Christus Victor understanding of salvation until I took a closer look at the way this confession was worded.

We readily admit that the proclamation of these broader elements of redemption may be inappropriately neglected, not only in churches which indeed have a narrow view of gospel blessings, but even in churches that explicitly confess a rich and broad understanding of the gospel. Preaching and liturgy absent of communicating the Lord’s victory through Christ over all of humanity’s enemies is surely deficient, and we do well to be self-critical if we have lapsed into such an imbalance. Rounded preaching and worship includes the gospel themes of restoration from ruin, repair of brokenness, victory over Satan, the glorification, and the like. [Emphasis added.]

The insertion of qualifiers such as “may” and “if” in effect empties the confession of its force. It would much like someone telling me: “Please forgive me if I may have done any wrong to you.” Such an apology is really a non-apology. It would have been much more meaningful if the Report admitted that the Christus Victor motif had in fact been neglected and that the Reformed tradition could learn something from Orthodoxy in this area.

In the section “Experience,” the committee notes:

Practically, we are concerned that when professing Christians flee to EO [Eastern Orthodoxy] for a kinder, gentler gospel, some are taking that path to evade accepting and confronting the horrific nature and extent of their sin, and cultivating a godly sorrow for it that leads to repentance (p. 28; emphasis added).

I found it amusing that the Report would accuse Orthodoxy of purveying a “kinder, gentler gospel” (p. 28). In Orthodoxy I am reminded more frequently of the danger of Hell (Hades) and of the need to repent of my sins. These reminders come not so much from the pulpit as in the liturgical services and in the various prayers found in Orthodox prayer books. Every year, just before Orthodox Lent begins, the Orthodox Church celebrates the Sunday of the Great Judgment in which Matthew 25:31-46 is read out loud to the entire congregation.

Be that as it may, the real issue that Report seems to have glossed over is Protestantism’s core dogma sola fide (justification by faith alone). Page 27 of the Report asserts that the “courtroom model” is the dominant framework taught in Scripture but does not support this position with evidence. There is no doubt that Scripture uses the courtroom model to explain Christ’s death. But, what is at issue here is whether the courtroom model is the central and dominant motif of Scripture, or one of many motifs of salvation found in the rich tapestry of Scripture. As a church history major at Gordon-Conwell I was puzzled by the relatively minor role of the courtroom model in the early Church Fathers’ explanation of Christ’s death on the Cross. Reading the early Church Fathers and the ancient liturgies made me conscious how my Protestantism blinded me to other motifs used in Scripture: ransom, liberation, enlightenment, ascension, healing, restoration, etc.

While the forensic paradigm may not be as prominent in Orthodoxy, it does take sin seriously. Orthodoxy with its view of sin as corruption and spiritual illness gives greater emphasis to the horrific effects of sin on the human soul. Orthodox Christians are confronted with the darkness within and the intractable self-centeredness in their preparation for confession. While forgiveness is an essential part of the sacrament of confession, Orthodoxy understands confession primarily as the healing of the soul.

In the subsection “Longing for Certainty” (p. 30 ff.), the Report raises some important questions about the Orthodox Church’s claim to be the true Church in light of other churches that also claim an ancient pedigree, e.g., the Oriental Orthodox. Christians concerned about historical continuity to the early Church will confront the fact that there are other churches that make a similar claim. Implicit to the Report’s skeptical stance is the assumption that no church body today can truly claim historical continuity with the early Church. But to take the position that there exists no historical link with the early Church has disturbing implications. One implication is that there is no one true Church, that all churches are man-made denominations and that each church preaches only a fragment of the Gospel. The absence of a true Church opens the door to theological chaos, relativism and syncretism, leaving us bereft and adrift from the true knowledge of God.

The Report’s skepticism about Orthodoxy’s claim to historical continuity raises an important theological question about church history: Do we believe in Jesus’ promise that he would send the Holy Spirit to guide the Church into all truth? (John 16:13) Do we believe that the miracle of Pentecost was confined only to the book of Acts and the first century, or that the miracle of Pentecost continued into the following centuries? This question becomes acute in the case of the Ecumenical Councils. Either one believes that the Holy Spirit guided the Ecumenical Councils or we believe that the decisions made at the Ecumenical Councils were that made by mere men. Reformed inquirers must settle the question: How does the Holy Spirit guide the Church? The Report states that Reformed churches have always confessed the great creeds of the ancient Church (pp. 16-17). However, it should be noted that for the Reformed tradition the ancient creeds are fallible human attempts to interpret Scripture (p. 14). On the other hand, Orthodoxy believes that the Ecumenical Councils definitively and authoritatively settled some of the major theological issues. This acceptance of the Ecumenical Councils has given Orthodoxy a theological unity and stability sadly lacking among Protestants and Evangelicals. The Reformed tradition has a multiplicity of Reformed creeds, many of them comprehensive and detailed in scope. Yet the sad fact remains that the Reformed tradition has become theologically incoherent as a result of the inroads of liberal theology and numerous church splits. The URCNA’s origin in a split from the CRCNA is evidence of this.

Icons

The URCNA report’s assessment on icons is found in two places: in the report itself (pp. 22-23) and in the appended report by W. Robert Godfrey “The Roman Catholic Church and History” (“Appendix on Icons” pp. 21-27). The brevity of the first discussion of icons (pp. 22-23) is due to its being part of the larger section: “Part III. Beauty” (pp. 18-25). The Report’s concern here is more with the sensory appeal of Orthodox worship—the gold overlay, candles, the smell of incense, and icons—as opposed to the four bare walls of Reformed worship.

Those drawn to the beauty of EO [Eastern Orthodoxy] have demonstrated an emotional/existential angst on account of which they flee to the refuge of EO worship. When surrounded by the gold and the icons, and when engulfed with the sweet smells of incense, converts have felt better about the struggles of life. The sensory atmosphere enables them to forget the troubles of the pilgrim life, if only for a moment, as they get caught up in the cosmic and eschatological beauty that they feel is breaking into their worship. (p. 23)

Artist depiction of Exodus 26:31

The Report criticizes Orthodoxy for relying excessively on the cultural aesthetics of imperial Byzantium. What the Report failed to address is the fact that so much of the aesthetics of Orthodox worship is traced first to Scripture, to Exodus chapters 25 to 31. While Calvinists have repeatedly pointed to the Second Commandment (Exodus 20:4-5), they failed to take into account the two contexts of the Second Commandment. The immediate context, the First Commandment (Exodus 20:2-3), forbids the Israelites from worshiping other gods. The Second Commandment is an application of the First. It pertains to the worship of other gods, not about how to worship Yahweh–that would come later. The broader context, the rest of Exodus has instructions about how to worship Yahweh. It contains instructions for the construction of the Tabernacle, a luxurious, aesthetically rich structure decorated with tapestries, gold overlay, and images. Close attention must be given to Exodus 26:1 and 31 which specifically instructed the Israelites to make images of the cherubim for the Tabernacle.

Make the tabernacle with ten curtains of finely twisted linen and blue, purple and scarlet yarn, with cherubim worked into them by a skilled craftsman. (Exodus 26:1)

Make a curtain of blue, purple and scarlet yarn and finely twisted linen, with cherubim worked into it by a skilled craftsman. (Exodus 26:31)

Depiction of Interior of Solomon’s Temple

The curtain with the image of the cherubim was to be hung over the entrance to the Holy of Holies (Exodus 26:33). That the image of the cherubim was prominently and centrally situated in the Tabernacle and not relegated to the sidelines speaks to the prominent role of images in Old Testament worship. This tradition of making images continued in Solomon’s Temple (see 1 Kings 6:29-33). It should also be noted that Solomon did not slavishly replicate Moses’ Tabernacle; embroidered tapestries were replaced with wooden panels with images of carved cherubim and overlaid with gold. Given the explicit endorsement of the use of images in the Old Testament place of worship, it comes as no surprise that Orthodox worship continues the biblical pattern. The bigger question that needs to be asked is why the Reformed tradition has strayed so far from Scripture with its characteristic four bare walls. This exegetical blind spot has yet to be addressed by the Report, Reformed apologists, and by the Reformed tradition as a whole. The Reformed critique of Orthodox worship goes far beyond conflicting aesthetics to the fundamental question as to which tradition has maintained fidelity to the biblical pattern of worship as presented in the Old Testament. These are not new issues or arguments but old ones that have been dealt with by the Church, most notably by the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II, 787). Why the Report chose to ignore and refuse to interact with the language of the Seventh Ecumenical Council is both interesting and telling.

I was disturbed by the Report’s claim that for the Orthodox icons possess more beauty than true preaching of the word (pp. 22-23). This is the first I heard of this. If an Orthodox person were to make such a statement, I would take issue with them pointing out that the Liturgy is really comprised of two liturgies: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. One cannot have one or the other; the proclaimed word of the Gospel leads to the incarnated Word in the Eucharist. As a matter of fact, if one comes late to church and misses the reading of the Gospels one ought not partake of the Eucharist, because hearing the Gospel is an important aspect of preparing for Holy Communion. How could one be properly prepared to receive the Body and Blood of Christ if one has not received his word presented in the Gospel reading?

The Apparent Novelty of Depicting Christ in Icons

Probably the most significant critique of icons is to be found, not in the Report itself, but in Robert Godfrey’s report which was appended to the Report. The bulk of Godfrey’s report focuses on the iconoclast controversy and engages in an extensive critique of the second Council of Nicea (787). He takes issue with the direct representation of Christ noting that this did not happen until 400 (p. 22). Godfrey cites two well respected Orthodox authorities: Kallistos (Timothy) Ware and Jaroslav Pelikan to make his case. Godfrey’s argument here must be addressed by the Orthodox.

My response to Godfrey’s allegation that icons depicting Christ represent a break in historic continuity is that icons must be understood in terms of the development of Tradition. The Christian Tradition is not static but dynamic. While the Christian Tradition underwent development in the centuries following the first century, it retained a certain fundamental continuity. The element of continuity can be seen in the acceptance of visual representations in early Christian churches that has roots in early Jewish worship. The element of development can be seen in the gradual acceptance of the direct depiction of Christ’s face. The novelty of the direct depiction of Christ—circa the fifth and sixth centuries—can be seen as a consequence of the early Church gradually coming to terms with the radical implications of the Incarnation. Another likely factor is that Greco-Roman paganism had been superseded by a Christianized Roman Empire.

The Incarnation was a revolutionary event with disconcerting implications. If God truly became human with a tangible body and visible visage—as John of Damascus argued—then direct representation of the Word-made-flesh is permissible. We find other similar scandalous implications stemming from the Incarnation. For example, the Incarnation opened the way for the divine Son to die on the Cross for the sins of humanity. The idea of a suffering Messiah was an early stumbling block for many first century Jews. In time the Incarnation would clash with Jewish monotheism. Early Jewish monotheism could not contain the mystery of the Incarnation. The breakthrough was made with the Unoriginate Father who eternally begets the Son, and later the Holy Spirit who proceeds eternally from the Father. In time the theological formula would emerge of God as one Ousia (Essence) in three eternal Persons (Hypostases). Thus, the Good News of Christ was preserved and defended through what appears to be theological innovations that ultimately carried out a conserving role for the Christian Faith. While Christian monotheism has roots in Jewish monotheism, it marks a break with Jewish monotheism with the development of the dogma of the Trinity. A static view of the development of doctrine would rule out “innovations” like “ousia” (essence), “hypostasis” and “propospon” (person), “consubstantial” (homoousios), and “Trinity.”

Thus, if one were to take a static view of the development of Christian theology, one would be compelled, not only to reject the direct visual representation of Christ in icons, but also to reject the doctrine of the Trinity and the two natures of Christ. Without the precise dogmatic boundaries set forth by the Ecumenical Councils, Christianity becomes susceptible to the return of ancient Trinitarian and Christological heresies. It should not surprise us that this is precisely what has happened in Protestantism. By dispensing with the dogmatic authority of the Ecumenical Councils in their adherence to sola scriptura, many Protestant denominations became receptive to the early heresies, e.g., Arianism in many liberal mainline Protestant denominations and Modalism among Oneness Pentecostalism. See Christianity Today article: “Christian, What Do You Believe? Probably a Heresy Says a Survey.”

The Incarnation has startling implications for church history. The miracle of Pentecost implies that the Incarnation did not terminate with Christ’s Ascension to heaven. Rather, the Incarnation entered into the flow of human history via the Church, the Body of Christ. Orthodoxy believes that the visible Church is truly the Body of Christ and that this visible Church is indwelt by the Holy Spirit who guides her into all truth (John 16:13). Orthodoxy believes that the Ecumenical Councils were not mere human gatherings but divinely guided by the Holy Spirit. We believe that the Holy Spirit, who inspired the Church in her formulation of the biblical canon, likewise inspired the Ecumenical Councils in their refutation of heresies. The premise of an ongoing Pentecost creates a radically different paradigm for understanding church history. If one accepts the idea of the Church as the Body of Christ then one becomes receptive to the idea of the development of Christian Tradition. An ongoing Pentecost provides a safeguard against the early Church straying from the Apostolic Faith into heresy and corruption as so many Protestants assume about church history. The Protestant tenet of sola scriptura is hostile to the development of Christian Tradition. The early Church and its Councils are accepted provisionally—so long as they are in agreement with the Protestant reading of Scripture. When the early Church clashes with a Protestant’s individual reading of Scripture, e.g., the veneration of icons, then the authority of the Bible is invoked and the early Church is dismissed out of hand.

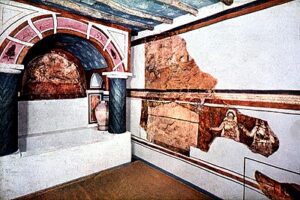

Baptistry – Dura-Europos Church

To summarize, the element of continuity can be seen in the early Church having images in places of worship as did the Jewish synagogues. Archaeologists have found images on the walls of both the church and synagogue in Dura Europos. These have been dated to as early as 250. The element of development can be seen in the gradual acceptance of the direct representation of Christ’s face after 400. It was this that apparently sparked the iconoclast controversy that would be resolved in the Seventh Ecumenical Council in 787 and reaffirmed by the subsequent council of 843. The theological debates over icons should not be viewed as being about church decoration but rather the continuation of earlier Christological and Trinitarian debates. The iconoclasts’ conservatism represents a failure to appreciate the implications of the Incarnation. Tragically, Reformed hostility to icons, which takes the form of four bare walls, does not hearken a return to the early iconoclasts who were tolerant of visual representations in churches, but to the more radical iconoclasm and the anti-Incarnation theology of Islam.

Finding Safe Haven — [Source: Sunrise at Storm Bay, Kiama – Kieran O’Connor]

Using the analogy of the radar, I would like to suggest that the negative findings of the URCNA report are mistaken identification. It would be like a radar technician mistaking the long, lost home port for an unknown threat. Whether or not Orthodoxy is really an enemy to true Christianity or a misidentified friend depends on the following questions: (1) Is Orthodoxy biblical?; (2) Is Orthodoxy consistent with early Christianity?; and (3) Is Orthodoxy Christ-centered?

The intent of the Reformation has been the recovery of the true Church. Thus, Protestants have long been on a quest for the true Gospel and the true Church. The Reformers believed that guided by the principles of sola fide (justification by faith alone) and sola scriptura (Scripture alone), they would be able to recover the apostolic Church lost as a result of the corruptions of Roman Catholicism. Despite centuries of sincere application of Protestantism’s two guiding principles, Protestant Christianity has come nowhere near to recovering the unity of early Church. Indeed, they have contributed more to weak doctrine and fragmentation. This can be seen in the URCNA’s own history, its splitting off from the CRCNA in reaction to theological liberalism in the CRCNA. Many Protestants and Evangelicals are distressed by the current state of affairs in their churches and denominations. This has led many to become open to Orthodoxy.

Many leaders of the Protestant churches upon learning of their parishioners’ interest in Orthodoxy have opened an investigation into Orthodoxy. Oftentimes what they find disturbs them, because it is at odds with Protestantism and with their understanding of early Christianity. They assume that early Christianity was originally Protestant in belief and practice. This is the core assumption of Protestant historiography. Protestant church history and Protestant theology stands or falls on the validity of this premise. The URCNA report represents a sincere attempt to defend the sixteenth century European theology of the Reformation against the ancient Church which exists in its present form in Orthodoxy. In this article I have sought to point out where the Report is mistaken in its critique of Orthodoxy and to point out that Orthodoxy is indeed the home port that Protestants have been yearning for over the centuries.

Quiet inquiry

The final section of the Report suggests ways for Reformed churches to deal with members drawn to Orthodoxy. One positive aspect of the final section is the latitude given to Reformed Christians quietly exploring Orthodoxy. The policy here is to allow with patient tolerance members exploring Orthodoxy.

While the person remains a member of one of our local churches, if they are exploring EO [Eastern Orthodoxy], reading, even attending an occasional service, patience on our part is an excellent virtue to exercise. As long as a person is not given over to promoting beliefs and practices inconsistent with their Reformed profession, let us seek to extend as much latitude as possible.

The advice that one not debate Orthodoxy with fellow Reformed Christians is a sound one, and one that I would give to inquirers. Quiet inquiry can take the form of visiting a Vespers service on Saturday evenings rather than Sunday mornings when one’s absence might be noticed. It could also take the form of visiting Orthodox Sunday services while traveling out of town. Or, one could arrange to meet with an Orthodox priest one-on-one in private. There are private Facebook groups that provide a safe place where Reformed inquirers can give voice to their questions and concerns without fear of reprisals. If one develops the conviction that Orthodoxy may be right in its claim to be the true Church founded by the Apostles, then attending Sunday services at a nearby Orthodox parish would be a logical next step. Inquiry into Orthodoxy should be done quietly, cautiously, and in a spirit of humility. Transitioning from the Reformed tradition to Orthodoxy is a radical step that should be done with care and much prayer. See my article “Crossing the Bosphorus.”

There is much that is commendable in the Reformed tradition. Many of us who converted to Orthodoxy do not regret our time in the Reformed tradition. We learned much that is valuable. Nonetheless, the Faith taught by the Apostles, kept by the Church Fathers, defined by the Ecumenical Councils, and celebrated in the Eucharist is far richer, profound, and healing.

Robert Arakaki

Further Reading

Report of the Committee Appointed by URCNA Classis SWUS to Study Eastern Orthodoxy.

“Confession of Dositheus.” The Voice: Christian Resource Institute.

Robert Arakaki. “Crossing the Bosphorus.” OrthodoxBridge.

Robert Arakaki. “Calvin Versus the Icon: Was John Calvin Wrong?” Liturgica.com

Robert Arakaki. “Christian Images Before Constantine.” OrthodoxBridge.

Fr. Wilbur Elsworth. “The Reformed Road to Orthodoxy.” Journey to Orthodoxy.

Keith Mathison. “Princeton vs. Mercersburg: Some Primary Sources.” Ligonier Ministries.

JKS Reid. “Confession of Faith concerning the Eucharist.” In Calvin: Theological Treatises, pp. 168-169.

David Rockett. “So-Baptist Jock, Then Happy Reformed-Calvinst 34 Yrs Finds The Orthodox Church!” Journey to Orthodoxy.

Jeremy Weber. 2018. “Christian, What Do You Believe? Probably a Heresy About Jesus Says Survey.” Christianity Today (October 16).

Recent Comments