Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick recently wrote “My Presbyterian Field Trip: A Fragmenting Tradition” in which he described a meeting at a church that was considering leaving the mainline Presbyterian Church (USA) for the smaller, more conservative ECO (A Covenant Order of Evangelical Presbyterians). The leader of the ECO was there to make the case for the move and a prominent member of the Missions Department of the PCUSA was there to urge the congregation to remain where they were.

My reaction to Fr. Andrew’s article was: “It’s déjà vu all over again.” As I read the article my mind went back to the early 1990s when my former home church had a meeting over whether to leave or stay in the liberal United Church of Christ (UCC). The UCC has historic roots going back to Puritan New England. The current controversy troubling the PCUSA faithful is nothing new. It is part of a widespread Protestant crisis-dynamic growing over the past several decades. As a matter of fact, this divisive-dynamic has been endemic to the Protestantism since its inception.

Source: Jacob Lupfer “Is the PCUSA *That* Liberal?”

Questions That Cannot Be Overlooked

As an interested outsider Fr. Andrew was able to see aspects of the theological dialogue that the participants were not aware of.

The differences between the two speakers were not always stark. For example, the PCUSA representative identified himself as an Evangelical. He noted that the PCUSA recognizes the authority of Scripture but that question was how one interprets Scripture. Fr. Andrew recognized this as a fundamental question that needed to be addressed but to his disappointment the ECO representative “just left it on the ground and essentially repeated himself.”

Probably one of the most insightful and probing question was the one posed by Fr. Andrew’s friend.

A related question was asked by my acquaintance (who works on the pastoral staff of the church), who inquired of the man from the PCUSA whether a tradition that has embraced as much diversity as they have can actually remain a coherent tradition. That was probably the biggest and most probing question of the evening, but it basically went unanswered.

Fr. Andrew recognized this as a crucial question that needed to be addressed, but because he was a visitor he remained quiet. In his mind came another question:

The question I would have liked to ask (and I did not, because I didn’t think it was my place; I was just an observer with no stake in the proceedings) would have been this: “How do you know that your interpretation of Scripture is the right one?”

Yet Father Damick’s question would likely have been ignored because Protestants have been trained to focus on Scripture and to ignore the critical role of tradition in our reading of Scripture. The issue of hermeneutics is something many Protestants are not prepared to question.

The Orthodox friend (former Presbyterian) who emailed me Fr. Andrew’s article asked: Why don’t they get it? Why aren’t they asking these questions? I wrote back saying that the two Presbyterian speakers were speaking from within their Protestant paradigm, and to ask deeper questions about the process by which one interprets Scripture and the criteria by which we know we have the right interpretation of Scripture would be far too unsettling and destabilizing for many Protestants.

The planetary axis of my Evangelical worldview tilted sideways when I began to question the hermeneutical basis for Protestant theology. The spread of theological liberalism in the United Church of Christ prompted me to join the Biblical Witness Fellowship, an Evangelical renewal group, and to go to Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. I wanted to be part of movement that would reverse the situation. I knew that critical to the reform of the UCC was bringing it back to its biblical and Reformation roots. However, as I considered the plurality of interpretive traditions within Protestantism, the diversity of confessional standards within the Reformed tradition, and their discrepancy with the unity of the early Church I could sense the tectonic plates shifting underneath my theology.

Scripture + Interpretation = Tradition

Many people assume that we just read the Bible but things are not that simple. As we read the Bible we seek to understand what it means and in doing this we engage in the act of interpretation (hermeneutics). Many people enjoy reading the Bible in the privacy of their own home but the fact is we all belong to a faith community (local church). As we seek to follow the teachings of Scripture we join with others who share the same understanding of what the Bible teaches. This shared understanding of what the Bible teaches is tradition. Some people desire to be free of human tradition, but there is no escaping tradition. Every local church has a shared tradition. A shared tradition is what brings coherence to the local church. This is a sociological reality. If this were not the case, the local church would be like a Christian bookstore full of customers with no commitment to their fellow customers.

It is oversimplifying things to say: Our church is based on the Bible. It would be more accurate to say: Our church is based on someone’s interpretation of the Bible. For example, the popular “non-denomination” Calvary Chapel is based on Pastor Chuck Smith’s reading of the Bible. As a gifted bible teacher he soon drew a faithful following that in time became a church – Calvary Chapel, Costa Mesa. As Chuck Smith’s teachings were disseminated over the radio and he trained younger men like Greg Laurie and Mike MacIntosh Calvary became a denomination – Calvary Chapel Association. Interestingly, while Calvary Chapel claims to have no theological tradition, it has a set of “distinctives.”

Every Protestant group believes their own tradition interprets Scripture rightly. The names: Presbyterian, Congregationalist, Lutheran, Baptist, Holiness, Anglican, etc., all refer to a particular interpretive tradition of the Bible. Differences in interpretations have led to new traditions and to church splits and new church groups giving rise to Protestantism’s perennial crisis. This includes even the two Presbyterian splinter groups here. Both PCUSA and ECO believe the Bible to be the word of God, they just interpret it differently which leads to the question: Who has the right interpretation?

This was the problem I faced when I took part in Evangelical-Liberal dialogues in the UCC. Rather than resort to detailed exegesis of the Greek text – the methodology of biblical studies, I argued for the Evangelical position making use of historical theology. I sought to show that it was the Evangelicals, not the Liberals, who were in historical continuity with the Protestant Reformers, and with the early Church Fathers and Ecumenical Councils. This strategy was to have surprising consequences for my Protestant theology.

By What Authority?

Unlike much of popular Evangelicalism which claims to be free of tradition, historic Protestant groups like the Presbyterians still see value in traditions like creeds. Yet despite their holding to historic confessions, a critically aware Reformed Christian cannot avoid certain unsettling questions. Fr. Andrew notes:

What exactly does a Presbyterian denominationalist point to say “This is the true Presbyterianism” or “This is the true Presbyterian church”? There are the various confessions and statements, of course, but no Reformed denomination is wholly faithful to them. After all, the ECO wants to be faithful to Presbyterian tradition by nixing homosexual sex yet wants to depart from that same tradition by ordaining women. If one element of tradition can be revised, why should another be sacrosanct? And on what authority were those original Reformed confessions ratified, anyway?

While Presbyterianism does have confessions but what good is it to have confessional statements if certain elements of the denomination disregard them for newer interpretations of Scripture? If the Reformation began with Luther putting forward a new interpretation of Romans against medieval Roman Catholicism, what is to stop subsequent generations of Protestants from putting forward newer interpretations that challenge the current status quo? Questions like these have caused increasing numbers of long-time Protestants to take a critical look at the hermeneutical basis for Reformed theology.

Protestantism’s Perennial Crisis

The theological crisis Fr. Andrew witnessed at his friend’s PCUSA church has been going on for a long time. It was there in the UCC in the 1990s. It occurred earlier with the formation of the PCA (Presbyterian Church in America) in the 1970s. It came to a head in the Episcopal Church in the early 2000s when Gene Robinson was made bishop.

It is happening now in other denominations. Two years ago in the United Methodist Church the Rev. Adam Hamilton called for the “local option” that would allow churches to “agree to disagree” on the denomination’s stance on homosexuality. Surprisingly, it is happening in the conservative Southern Baptist denomination. This year, a Southern Baptist pastor, Danny Cortez, called for a Third Way in which people could “agree to disagree” on the issue of homosexuality. Subsequent to the church’s vote to retain him as pastor, the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee voted to disfellowship Pastor Cortez’s church. This theological crisis is likely to go on for years to come. On both sides are people who affirm the authority of Scripture but disagree over how to interpret Scripture. What is a confused Protestant to do?

A Way Out of the Hermeneutical Chaos

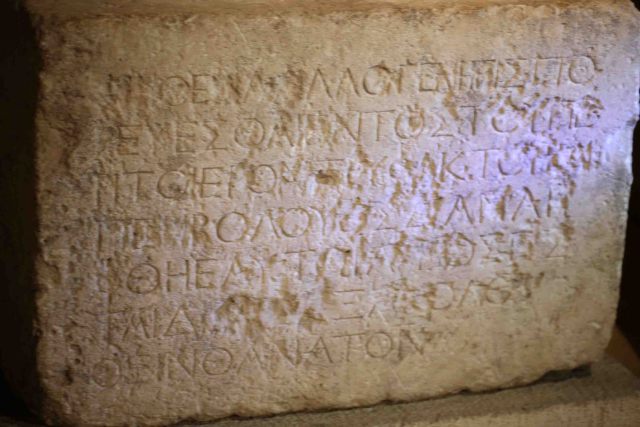

When I was studying the early church I came across a statement by Irenaeus of Lyons that haunted me as a Protestant. Irenaeus wrote Against Heresies at a time when the early Church was faced with the Gnostic heresy.

He wrote:

Having received this preaching and this faith, as I have said, the Church, although scattered in the whole world, carefully preserves it, as if living in one house. She believes these things [everywhere] alike, as if she had but one heart and one soul, and preaches them harmoniously, teaches them, and hands them down, as if she had but one mouth. Source

Though it had many problems and was full of sinners, the early Church was united in faith. This is so different from modern Protestantism which is tragically divided and confused. In contrast to modern Protestantism’s plurality of interpretive traditions, the early Church had resources for preserving a coherent reading of Scripture. It had the office of the bishop grounded in apostolic succession, the “rule of faith” (creed) which was taught to those about to undergo baptism, the Ecumenical Councils which settled matters of theological controversy, and the Liturgy which framed the reading of Scripture. All these together comprise Holy Tradition. Scripture is understood to be embedded within the Apostolic Tradition from which it emerged and safeguarded and passed on by the Church. Holy Tradition is in reality, life of the Holy Spirit who indwells the Church founded by Christ himself (Matthew 16:18).

Like many other Protestants frustrated with Protestantism’s hermeneutical chaos I began to critically reexamine sola scriptura and in the process was drawn to the early Church. As a way of responding to the crisis spawned by Protestantism’s theological incoherence I wrote two research papers that enabled me to make the critical transition from the Reformed tradition to Orthodoxy:

“If Not Sola Scriptura, Then What? The Biblical Basis for Holy Tradition.”

Like thousands of others before and after me I crossed the Bosphorus and became Orthodox. In Orthodoxy’s ancient Faith we have found safe haven in the Church. For those troubled by Protestantism’s theological woes, Orthodoxy offers the stability of an ancient Faith that has withstood the test of time and cultural shifts.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments