Sola Scriptura’s Epistemological Problems (4 of 4)

A Response to David Roxas (3 of 4) See also: (2 of 4) and (1 of 4)

Within the Protestant tenet of sola scriptura are significant epistemological problems. I list them below and describe how Orthodoxy addressed these problems.

First, if Scripture is divinely inspired but interpreted by flawed, fallible men, then how do we know that we have the right interpretation and not some heretical misinterpretation? Most Protestants would answer in one of two ways. They might assert: “It makes perfect sense. It’s logical.” A more sophisticated version of this takes the form of: “By using the most advanced tools of scientific exegesis we can objectively ascertain the meaning of the biblical text.” Or, they might say: “The Holy Spirit showed me the true meaning of Scripture.” Both answers point to Protestantism’s individualism and subjectivism, especially when these interpretations are assessed against church history.

In their struggle against heretics the early Church Fathers did things differently. They cited written Tradition (Scripture) which they had received from the Apostles, and they interpreted Scripture according to the oral Tradition which they also had received from the Apostles. Irenaeus raises the question of how to find the truth when there is a doctrinal controversy. He writes:

Suppose there arise a dispute relative to some important question among us, should we not have recourse to the most ancient Churches with which the apostles held constant intercourse, and learn from them what is certain and clear in regard to the present question? For how should it be if the apostles themselves had not left us writings? Would it not be necessary, [in that case,] to follow the course of the tradition which they handed down to those to whom they did commit the Churches? (Against Heresies 3.4.1; ANF pp. 416-417; emphasis added)

In the above passage, we see that Irenaeus would not have commend sola scriptura as a means for resolving theological controversy. He recommends that we look to the “most ancient Churches.” Then he notes that if the Apostles did not leave us a written record on disputed topics, then we ought to follow the tradition handed down to their successors, that is, the bishops. Athanasius the Great made a similar appeal to Tradition. In his letter to Bishop Serapion he writes:

In accordance with the Apostolic faith delivered to us by tradition from the Fathers, I have delivered the tradition, without inventing anything extraneous to it. What I learned, that have I inscribed conformably with the holy Scriptures; for it also conforms with those passages from the holy Scriptures which we have cited above by way of proof. (§33; emphasis added)

While Athanasius speaks highly of Scripture, he would not have advocated Protestantism’s sola scriptura. Rather, what we find is Tradition with Scripture as taught by Orthodoxy. Athanasius commended the passing on of Tradition by the Church Fathers, something that Protestants do not advocate.

Zwingli and Luther at the Marburg Colloquy (1529) – two rival interpretations of the Bible

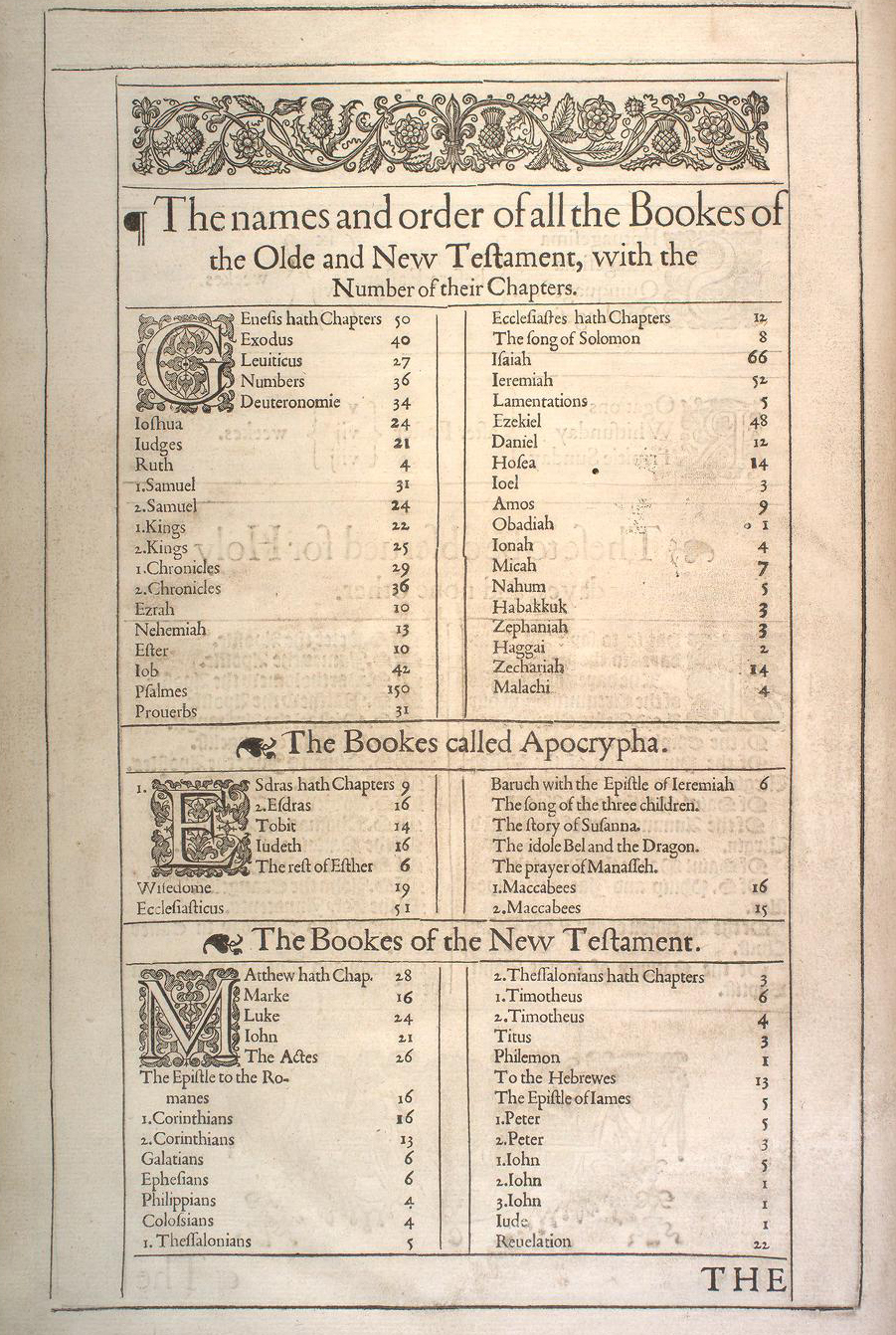

Second, if Scripture is the true revelation from God, how do we deal with competing interpretations of the Bible? Within Protestantism there are those who believe the Bible teaches double predestination while other sincere Protestants affirm free will; some believe in a literal one-thousand-year reign of Christ on earth, while others prefer to understand Revelation 20 as symbolic; and some Protestants believe that miracles have ceased, while others believe that charismatic gifts are with us today. The plethora of conflicting interpretations of the Bible has given rise to thousands of Protestant denominations – all of them claiming fidelity to sola scriptura. This raises the question as to whether truth is multiple or whether there is one reading of Scripture that is true and all others are wrong. If there is only one true interpretation, then how can we find our way among the many readings within Protestantism?

Orthodoxy understands Scripture within the framework of the patristic consensus, the Divine Liturgy, and the Ecumenical Councils. All these interrelate organically. The early Church Fathers, for the most part, were bishops who celebrated the Divine Liturgy every Sunday and who expounded Scripture in the Liturgy. The Church Fathers who attended the Ecumenical Councils likewise, for the most part, were bishops — successors to the Apostles. We need to keep in mind that at their ordination, they were charged with safeguarding what the Apostle Paul called “the good deposit.” (2 Timothy 1:14)

Orthodoxy does not have systematic theology texts like those in Protestantism. The closest thing Orthodoxy has to a systematic theology is the Divine Liturgy. Every Sunday I hear the Church’s teaching on Christ being fully divine and fully human, his saving death on the Cross, his Resurrection, his Second Coming, the kingdom of God, and God as Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Liturgy provides Orthodoxy a doctrinal stability that has served it well for two millennia.

Martin Luther at the Diet of Worms – “Here I Stand!”

Third, sola scriptura is implicitly individualistic and thus anti-Church. There is within Protestantism a strong distrust of the Church having the authority to interpret the Bible. Many Protestants believe that they as individuals have the Holy Spirit and that the Holy Spirit guides them individually to the “true meaning” of the Bible, no matter that this “new insight into the Bible” is at odds with so many others. This individualistic attitude has troubling implications. Can you imagine a first-year medical school student rejecting the teachings of the faculty? Or a local attorney putting his personal interpretation of the Constitution over the precedents set by the Supreme Court?

This third assumption in effect constitutes a rejection of the promise of Pentecost. When Jesus promised the Holy Spirit in the Upper Room Discourse, he used the plural you. As one person noted humorously that Jesus was using the Southern “Y’all” form of “you.” The plural you points to the Holy Spirit being given to the Church as a corporate body, not to individuals. This is the basis for the Church’s authority to define doctrine for its members.

But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you [ὑμᾶς] all things and will remind you [ὑμᾶς] of everything I have said to you [ὑμῖν]. (John 14:26; NA28)

But when he, the Spirit of truth, comes, he will guide you [ὑμᾶς] into all truth. (John 16:13; NA28)

In Acts 2, we read how the Holy Spirit descended on the assembly of believers. In Acts 13, we read how the Holy Spirit guided the Church in Antioch to consecrate Barnabas and Paul to the missionary calling. In Acts 15, we are told that the Holy Spirit guided the early Church through its first theological crisis (Acts 15:28). In all three instances we see the Holy Spirit guiding the early Christians as a corporate body. To assert: “I have the Holy Spirit and others do not,” manifests an individualistic attitude that is so contrary to the spirit of humility and solidarity that runs through the Bible and what it teaches about the Church.

Orthodoxy believes that the Holy Spirit was present in the early Church guiding the early bishops as they celebrated the Eucharist, discerned which writings were to be regarded as inspired Scripture, and expounded on the true meaning of Scripture. The Holy Spirit later guided the Church Fathers as they refuted heresies, and made historic rulings at Ecumenical Councils. Holy Tradition in its varied forms – the Liturgy, the episcopacy, the Nicene Creed, the Ecumenical Councils, the patristic consensus, all inspired by the Holy Spirit – has given Orthodoxy a doctrinal stability and profound spirituality that has served it well for two millennia.

Seminarians Studying (“We Need a Neo-Evangelical Shakedown“)

Fourth, sola scriptura is implicitly secular. Among many Protestants is the belief that the Holy Spirit was active during the lifetime of the Apostles, especially during the writing of the New Testament, but once the New Testament was completed and the last Apostle died, the Holy Spirit then retreated into heaven. Shortly after that, the Church fell into ritualism, false teachings, and spiritual darkness until the Protestant Reformation. (See Ralph Winter’s BOBO theory.) Protestantism’s rejection of the papacy led to a greater reliance on the human intellect. Among many Protestants, notably in the Reformed tradition, is the belief that the right understanding of Scripture is best guaranteed through knowledge of Greek and Hebrew, textual criticism, and a good training in scientific exegetical approach acquired at seminary. They then supplement all this by keeping up with the latest trend in biblical scholarship. In doing so, they place academic scholarship ahead of and in place of the Church, despite Christ’s promise that He would send the Holy Spirit, who would lead them into all Truth. This attitude has led many Protestant Reformers and present day Evangelicals to disregard the teachings of the Church Fathers and Ecumenical Councils when these contradict their own interpretation of Scripture. From the Orthodox perspective this attitude is tragic as we consider the Church Fathers and the Ecumenical Councils the Holy Spirit’s gift to the Church founded by Christ. As noted earlier, to reject the Church Fathers and the Ecumenical Councils is to reject the promise of Pentecost.

Tragically, the conclusion we draw from the findings presented above is that sola scriptura’s individualistic, modern epistemology, by rejecting Orthodoxy’s sacramental, Holy-Spirit-inspired hermeneutics, contradicts historic Christianity and the Scriptures that they claim to revere. Lord have mercy.

Robert Arakaki

Recommended Readings

Robert Arakaki. 2012. “Pentecost and the Promise of God Fulfilled.” OrthodoxBridge (29 June 2012)

Robert Arakaki. 2016. “Early Church Fathers: Babies or Giants?” OrthodoxBridge (10 June 2016)

Robert Arakaki. 2014. “Calvin and the ‘Fall of the Church.'” OrthodoxBridge (29 January 2014)

Ralph D. Winter. 1981. “The Kingdom Strikes Back: Ten Epochs of Redemptive History.”

Recent Comments