With its many denominations Protestantism is no stranger to people changing churches, but there is something deeply unsettling about a Protestant family deciding to move over to a nearby Orthodox parish. The phrase “swimming the Tiber” or “crossing the Bosphorus” alludes to the deep chasm separating Protestantism from the two ancient traditions of Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Constantinople, the site of Orthodoxy’s leading patriarchal see, is located next to the Bosphorus, a narrow strait that separates Europe from Asia. Thus, there is a certain aptness to the Bosphorus as a symbol of the divide between Orthodoxy and Protestantism.

In this blog posting I will discuss the significance of switching over from Protestantism to Orthodoxy. I will be using three issues to explore the Protestant versus Orthodox divide: the authority to interpret Scripture, the visible church as the true church, and the meaning of Communion. I will also discuss the reactions Protestants looking into Orthodoxy may encounter from their fellow Protestants and give advice to Protestants thinking about becoming Orthodox.

Relinquishing Sola Scriptura

Protestantism is based on the doctrine of sola scriptura (the Bible alone). A corollary to sola scriptura is “soul competency,” the notion that the individual Christian is competent to interpret Scripture for themselves because they have the Holy Spirit in them as a result of the born again experience. While historic Protestant churches have tempered this view by insisting on a learned clergy and confessional statements like the Westminster Confession, all these were jettisoned on the American frontier in the early 1800s. This gave rise to an extreme version that eschews learned clergy and creeds. This view is popular among Evangelicals and other conservative Protestants today. All across Protestantism, regardless of denomination, the authority to interpret Scripture is assumed to rest with the individual. You join a church because they have the same understanding of the Bible as you do, and because doing so is consistent with your conscience. For Protestants there is no universally binding doctrinal authority apart from Scripture.

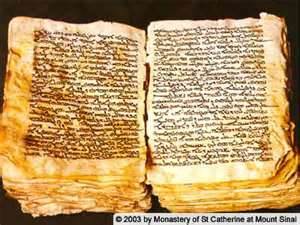

One reason why converting to Orthodoxy is so unsettling lies in the fact one must reject the notion of soul competency which accompanies sola scriptura and submit to the Church’s teaching authority. Orthodoxy claims that because it has received and preserved the Apostolic Tradition it has the right interpretation of Scripture (II Thessalonians 2:15). This claim is supported by the lists of episcopal succession for the various patriarchates such as Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. Furthermore, the Orthodox Church claims that Christ’s promise that the Holy Spirit would guide the Church into all truth (John 16:13) was fulfilled in the formation of the biblical canon and the Ecumenical Councils. It was at the Seven Ecumenical Councils that the Christian Faith was affirmed and heresy rejected. And it is thanks to the early Church that we have the Bible we have today.

Many Protestants troubled by Protestantism’s doctrinal anarchy have reached the conclusion that sola scriptura as a theological method is unworkable. This has led them to seek doctrinal stability in the older Christian traditions. This quest for doctrinal stability has led many to the Orthodox Church. Questions about sola scriptura were what precipitated the theological crisis that led this author to Orthodoxy.

Accepting the Visible Church

The Orthodox Church’s claim to be the true Church is a second reason why Protestants crossing over to Orthodoxy is unsettling. This is contrary to the widespread belief among Protestants that the true church is the invisible church comprised of all born again Christians. Basically, it means that the true Church is everywhere and nowhere. In contrast, Orthodoxy asserts that the true Church can be found in the visible entity called the Orthodox Church.

Orthodoxy believes that there has always been one Church. The Church has never been divided into two or many branches. Such a notion contradicts Christ’s promise that he would build the Church upon the rock (Peter’s proclamation that Jesus is the Christ) and that the gates of hell would not prevail against the Church (Matthew 16:18). For this reason the belief by some Protestants that the early visible church fell into apostasy and corruption leaving only an invisible faithful remnant is heresy. Similarly, Orthodoxy rejects the branch theory that the true Church can be found among either Orthodox, or Roman Catholic, or Anglican churches.

The troubling implication here is that Protestant churches are not really churches and that to be a Protestant is to be outside the true Church. In Protestantism if one’s belief changes then one change churches through a letter of transfer of church membership. This is a common practice done all the time. But in the case of a Protestant becoming Orthodox, a letter of transfer is null and void. To become Orthodox one must go through the sacraments of conversion: baptism, chrismation, and Communion.

Recently many Evangelicals have reacted to the extremes of the invisible church view and embraced the high view of the church espoused by Calvin and other Reformers and the ecumenical movement’s vision of restoring visible church unity. Among them are some who claim to be more “catholic” than the Catholic Church! They view doctrinal differences between Protestantism and Orthodoxy as arbitrary lines drawn in the sand, unnecessarily divisive and obstructive to “true” church unity. They believe that we can enter into ecumenical dialogue, negotiate our differences, and make compromises and adjustments that will result in church unity. An Orthodox Christian can only be skeptical of such a claim. To take this route is to define the Church according to what we want rather than following Apostolic Tradition. Because Orthodoxy will never compromise Holy Tradition this kind of ecumenical venture is unfeasible.

The Meaning of Holy Communion

There are two things Protestants find disturbing about the Orthodox approach to Holy Communion. One is that Orthodoxy believes that in the Eucharist we feed on Christ’s body and blood. This is something all the early Christians believed, but sadly many Protestants today believe that Holy Communion is just a symbolic reminder of Christ’s death. More traditional or high church Protestants might protest that they too like the Orthodox Church believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. But this claim is highly suspect in light of the fact that they lack bishops and have no apostolic succession. Without apostolic succession there is no covenantal authority to perform the Eucharistic sacrifice.

When I was a high church Calvinist (Mercersburg Theology), I strongly believed in the real presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. But one day I realized: “They’re right. It’s just a symbol. It’s a symbol because it’s not the real thing. It’s not the real thing because there’s no valid priestly authority to consecrate the elements.” I was at an InterVarsity Christian Fellowship student retreat when I had this realization. InterVarsity is a parachurch organization, but as I began to think about the more established Protestant churches I realized with a sinking feeling in my stomach they were in the same boat as InterVarsity – lacking proper covenantal authority that comes from apostolic succession.

Furthermore, the claim to a valid Eucharist is suspect in light of the fact that much of Protestantism is at odds with the Seven Ecumenical Councils. For example, to use the Filioque version of the Nicene Creed is in violation of Canon VII of the Third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus 431) which prohibits alteration to the Creed. To refuse to honor Mary as the Theotokos (Mother of God) is to reject the Third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus 431). To refuse to venerate icons is to reject the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II 787). In light of these numerous deviations from the Ecumenical Councils it is highly doubtful that Protestantism can claim doctrinal agreement with the early Church. There can be no valid Eucharist where heresy is embraced and promulgated. And even if a person or a congregation did agree with all of the above points, they would need to be in communion with the five ancient patriarchates: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem, endorsed by the Ecumenical Councils (see Canon VI and VII of Nicea I (325), Canon III of I Constantinople (381), and Canon XXVIII of Chalcedon (451)). (Note: It is tragic that the Schism of 1054 has resulted in Rome’s departure from the ancient Pentarchy. While Orthodoxy disagrees with the Roman Catholic Church, it recognizes its episcopal lineage as one going back to Saints Peter and Paul.) Thus, unless one is in communion with one of the ancient patriarchates one’s link to the early Church is imagined and not real.

Another unsettling fact is that Orthodoxy practices closed communion, that is, Communion is reserved only for those who belong to the Orthodox Church. Lutherans or Anglicans who hold a high Christology and affirm the real presence in the Eucharist become upset when they learn that they are barred from receiving Communion in an Orthodox Church. They view this as a judgment on their faith in Christ but this is not the case. In Orthodoxy receiving Communion means that one accepts the Tradition of the Church and that one submits to the magisterium (teaching authority) of the Orthodox Church in the person of the local bishop. For me to receive Communion at Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church in Honolulu puts me under the authority of Metropolitan Gerasimos of San Francisco and in communion with Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople. Therefore, communion in Orthodoxy is not just a matter of being in doctrinal agreement with the bishop but submitting to his authority as well.

Becoming Orthodox

The general pattern in the Greek Orthodox Church is for Protestants to be received into the Orthodox Church through the sacrament of chrismation and the receiving of Holy Communion. Prior to that the priest will ask for evidence or documentation that one has been baptized in the name of the Trinity, that is, baptized in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Most Protestant denominations follow this practice, but some baptize in Jesus’ name (e.g., Oneness Pentecostalism); for Orthodoxy this is not a valid baptism. Similarly, a baptism done in a liberal church using inclusive language like: Parent, Child, and Holy Spirit, will be rejected. Some Orthodox jurisdictions, like the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, are especially strict and will insist that all Protestants and even Roman Catholics be baptized for reception into the Orthodox Church.

As much as one might desire to become Orthodox, the decision is made by the priest with the approval of the bishop. Some Orthodox priests will insist that one attend the Liturgy for at least a year to show one’s seriousness about becoming Orthodox and in order to learn what Orthodoxy is all about. Other priests will want you to attend a 24 week class along with regular Sunday attendance. The priest is concerned not just with how much doctrine you understand, but also with your commitment to the worship life of the Church, your willingness to accept the spiritual disciplines like fasting, and your willingness to submit to the authority of the Church.

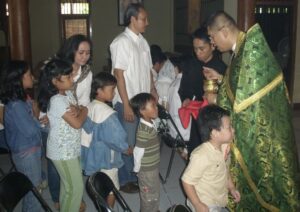

The Orthodox attitude towards people wanting to become Orthodox is that of welcome and caution. We want people to become Orthodox, but we also want them to realize the seriousness of the commitment. We often counsel patience in the case of people who are married and have children. We prefer the whole family become Orthodox in due time rather than the father becoming Orthodox right away with the wife and the children remaining Protestant. Orthodoxy believes that God intended the family to be a spiritual unity. Conversely, a spiritually divided household falls short of the ideal. Oftentimes patient waiting can result in a greater blessing for more people. That is why sitting down with the priest is so critically important. Letting the priest guide you in transitioning to Orthodoxy is a key step in learning to humbly submit to pastoral authority (Hebrews 13:17).

Due Diligence

The famous investment guru, Warren Buffet, before making a major purchase in a company does due diligence. He researches the company’s history, its performance record, as well as its assets and liabilities. To not do this is irresponsible. Similarly, with respect to having the right faith and ensuring the spiritual well being of one’s family, it is important that due diligence be done before converting to Orthodoxy.

I recently had pleasant breakfast conversation with ‘Jim’ who was raised in an ethnic Orthodox parish. Because there was very little emphasis on explaining the Orthodox faith in that parish, he drifted over to Calvary Chapel. Recently, he started looking into Orthodoxy and was pleasantly surprised to find the spiritual and biblical depths of Orthodoxy. While strongly drawn to Orthodoxy and thinking about returning to Orthodoxy, ‘Jim’ is at the present time still a Protestant. Some of his Calvary Chapel friends became quite concerned and warned him that he might lose his salvation. In our conversation over pancakes and coffee we talked about the Bible and the Orthodox faith. He is, as he puts it, doing “due diligence” by studying Orthodoxy and looking carefully at the Scriptural and historical evidence. I admired the wisdom of his approach and recommend this for others.

Folks considering becoming Orthodox should at a minimum do the following:

-

- Read basic works like Timothy Ware’s The Orthodox Church,

- Attend the Divine Liturgy several times,

- Meet one on one with an Orthodox priest, and

- Complete a catechism class if offered.

Joining the Orthodox Church is a lifetime commitment. It is more than agreeing with a theological system; it also entails a commitment to a way of life and submission to the teaching authority of the Church. Unlike cults, clerical authority in the Orthodox Church is circumscribed by Holy Tradition. There is no secret hidden Tradition. Neither will there be a new doctrine or a new marriage ceremony coming down from the denominational headquarters. Everyone in the Orthodox Church, from the newest convert to the bishop, is constrained by Holy Tradition. And just as important everyone, both laity and clergy, is responsible for guarding Holy Tradition.

Protestants who read a lot or have gone to seminary may find it harder to become Orthodox. They have a lot more to unlearn. It took me several years to review my Protestant beliefs and come to the point where I could sincerely and intelligently renounce my Protestant beliefs. (I could not in good conscience do a theological lobotomy.) Having gone to a leading Reformed seminary and majored in church history I knew that the core of Protestant theology rested on the five solas: sola scriptura, sola fide, sola gratia, solus Christus, and soli Deo gloria. It was the questions about sola scriptura that started my theological crisis, but it was sola fide that was the straw that broke the camel’s back. When I reached the conclusion sola fide was based on a misreading of Scripture and was never taught by the early church fathers, I realized that my days as a Protestant were over.

How much does one need to know before one becomes Orthodox? If becoming Orthodox is like getting married, then the catechumenate is like courtship. During the dating phase you check out the other person, you find out what they’re like, their likes and dislikes, you spend time with them, and then you ask yourself: Do I want to spend the rest of my life with so-and-so? Becoming Orthodox is really about making a commitment to Jesus Christ the head of the Church. Everything in Orthodoxy is for the purpose of uniting us with Christ. The Liturgy is not just a beautiful ceremony; we receive the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist. Whenever we behold the Virgin Mary, we see the one who said: “Do whatever He (Jesus) tells you” and whom the Church honors as the Mother of God. So the basic question is: Is this the Church founded by Jesus Christ?

Many inquirers come to Orthodoxy with theological concerns. However, it is important to keep in mind that Orthodoxy is more than a theological system. It leads us into the mystery of God. Orthodoxy teaches that beyond our conceptual understanding of God is the mystical encounter that is beyond words. We come to a true knowledge of God through worship. That is why the Divine Liturgy lies at the heart of Orthodoxy. There is an ancient saying: “If you are a theologian, you will pray truly; if you pray truly, you are a theologian.” This emphasis on mystical knowledge in Orthodoxy stands in contrast to the Western Christian tradition which emphasizes scientific study of the biblical text and reliance on logic for doing theology.

Transitioning to Orthodoxy

My transition from Protestantism to Orthodoxy was gradual and low key. My former home church had several Sunday morning services. I would often attend the 7:30 service then head over to the Greek Orthodox Church for the 9:30 Liturgy. When the priest offered an Orthodoxy 101 class on Thursday night I would go without raising any eyebrows. This is the Nicodemus stage of quiet inquiry (John 3:1-2). The main value of the Thursday night class was that I could find out whether I had a good grasp of what Orthodoxy was about.

For me the biggest obstacle to becoming Orthodox were issues like sola scriptura, icons, and sola fide. I handled the problem like any good graduate student, I wrote research papers. To my great surprise Orthodoxy was indeed biblical in its teachings. I remember the moment when sola scriptura fell apart and I said to myself: “My God! I’m going to have to become Orthodox!” When sola fide fell by the wayside, I met quietly with the leaders of the church and shared with them my decision to become Orthodox. I also gave them the opportunity to talk me out of it. Part of me desperately wanted them to talk me out of it because I knew becoming Orthodox would change our relationship in very fundamental ways. Unfortunately the Evangelical response was not a vigorous one. I remember the dean of a local Evangelical seminary responding to my paper on sola scriptura by asking: “Have you read Packer’s Fundamentalism and the Word of God?” My response was a mildly exasperated: “Yes, I’ve read Packer, so what about my critique of sola scriptura?” I didn’t hear anything more from him. My pastor wasn’t able to rebut my critique of sola fide. I remember thinking in my head in dumbfounded amazement: “That’s it!?!? You mean I’m going to have to become Orthodox?!?!” Even now I find myself baffled and disappointed by the unwillingness of many Protestant pastors and theologians to defend the basic tenets of Protestantism.

Going Through Customs

A common experience when travelling abroad is going through customs. One purpose of customs to prevent contraband items from entering the country. When I was received into the Orthodox Church the priest asked me: “Do you renounce all heresies, ancient and modern?” This was a big question because it meant not just the ancient heresies of Arianism and Nestorianism but also Protestant doctrines like sola scriptura and sola fide, dispensationalism, double predestination, congregationalism etc. I was ready for that question because I had read up on Orthodoxy, attended the Liturgy, attended the catechism class, and spoke with the priest. For me there was no surprise, I knew that there would be big changes but I was prepared. Becoming Orthodox did not mean I rejected my Evangelical past. I took with me many good things from Evangelicalism: a love for studying Scripture, the discipline of daily prayer, and a passion for world evangelism.

Once I met with a former Protestant who had converted to Roman Catholicism. For some strange reason he didn’t know about the Pope’s infallibility when he joined the Catholic Church. Later when he was reading the official catechism he learned that anyone who did not accept the Pope’s infallibility was a heretic. ‘Hank’ told me he sat there stunned with the realization that in the eyes of the Catholic Church he was a heretic, but he stayed on because of his godson. It was a short breakfast meeting, but as I drove to the airport I reflected on his perplexing story. Two thoughts came to me: (1) he was probably catechized by folks who glossed over some of the more difficult aspects of Roman Catholicism, and (2) “‘Hank’ you were snookered!” The lesson to be learned is that leaving Protestantism is going to be a costly decision and one needs to have done the necessary due diligence prior to making that change.

Border Crossings

We live in interesting times. There once was a time when hardly anyone knew about the Orthodox Church. But that is changing as growing numbers of people become interested in Orthodoxy and even go so far as to become Orthodox. But why the change? I suspect that it is due to massive changes in the Protestant landscape following World War II. Up till then, denominational lines remained stable but that began to change dramatically. Now we have Fundamentalists discovering Calvin, and Calvinists rediscovering the church fathers; we have Pentecostals becoming Anglicans, and we have Evangelicals becoming post-Evangelicals or Emergent Christians. In addition to all this confusion is the growing apostasy among the mainline Protestant denominations.

The situation today is much like the early days of the Cold War before the Iron Curtain came down. In the early days the borders were relatively open. Many families quietly packed their belongings and crossed the border in the dark of the night. But as growing numbers of people began to leave, the authorities became alarmed and finally began erecting the infamous Berlin Wall to keep their people in.

Similarly, many Protestant families today quietly say goodbye to their friends and start worshiping at a nearby Orthodox parish. There are reports of a growing uneasiness in certain leadership circles. Interest in Orthodoxy or in icons and the saints is discouraged or viewed as drifting away from the true faith. People expressing an interest in Orthodoxy are warned that they could be in danger of losing their salvation. In such a situation a chill is in the air and a feeling of distrust comes between once close friends. In some churches they come under closer pastoral surveillance, pressured not to stray from the true faith, and even excluded from certain functions in the church for fear that they might infect others with their interest in Orthodoxy.

I am glad in that my former home church provided me with a warm Christ centered fellowship where I could study Scripture, and read up on theology and church history. I found it quite frustrating that many of my Evangelical friends were not able to understand the questions I had about the basis for Protestant theology. So when I became Orthodox, many were surprised and a little confused, but we remain friends. My experience has been more like a friendly border crossing. I picked up my belongings and one Sunday morning I crossed the border into the Orthodox Church.

I feel sad for those whose transition has been marked by suspicion and judgment. It is my hope that open relations between Protestants and Orthodoxy will not be replaced by a Cold War atmosphere marked by barbed wires and aloof guards with grim stares. Barbed wires and restricted exit are signs of defensiveness and tyranny. An open and healthy society is marked by hospitality to strangers and mutual respect among its members. More preferable is a Glasnost in which Protestants can read up on the early church fathers and the Ecumenical Councils, and investigate the issues of icons, the Virgin Mary, and liturgical worship. In this period of openness curious Protestants should feel they have the freedom to visit the Orthodox worship services and come back with questions about what they saw. The best defense is not: “Those people are wrong!” but “Come and see!”

The Pearl of Great Price

Someone reading this blog posting might be thinking to themselves: “Why would someone give up all the benefits of Protestantism to become Orthodox?”

The Glorious Pearl – Domenico Fetti

My answer is Matthew 13:44-45:

The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field. When a man found it, he hid it again, and then in his joy went and sold all he had and bought that field.

Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a merchant looking for fine pearls. When he found one of great value, he went away and sold everything he had and bought it. (NIV; emphasis added)

If the Orthodox Church has kept the teachings of the Apostles intact for two thousand years, if there is only one true Church, and if the Eucharist is truly the body and blood of Christ given for you, wouldn’t that be enough reason to come home to the Church of the Apostles?

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments