“Five Reasons Why I am not Orthodox”

A reader asked for my thoughts about Pastor Jordan Cooper’s YouTube video “Five Reasons I am not Eastern Orthodox.” In this quite brief (15 minutes) video, Jordan Cooper concisely and eloquently gives his reasons for not converting to Orthodoxy. I very much enjoyed the thoughtful, irenic spirit of his presentation. While Pastor Cooper is an ordained Lutheran minister, his reasons for not converting echo the objections of many Reformed Christians. It is my hope that this article will stimulate a friendly and frank conversation between Protestants and Orthodox.

Objection 1 – Apophatic Theology

Pastor Jordan Cooper brings up apophatic theology (theology without words) as a great dividing factor between Orthodoxy and Western Christianity. He explains that apophatic theology uses the method of negation—stressing what God is not. In apophatic theology we strip away all thoughts and concepts of God. This way of doing theology is intertwined with Orthodox spirituality which stresses wordless, thoughtless prayer.

I was surprised and yet not surprised to hear Pastor Cooper bring up Orthodoxy’s apophaticism as an issue. I first learned about apophatic theology in my initial readings about Orthodoxy. However, in my journey to Orthodoxy as I met Orthodox Christians, attended the Sunday liturgies, and read the Church Fathers, the apophatic method was more in the background. As a matter of fact, when it comes to the typical week-by-week life of an Orthodox Christian, there is very little mention of apophatic theology.

There is a strong cataphatic (theology with words) element in Orthodoxy. When one hears the elaborate prayers said by the Orthodox priest in the Anaphora (Eucharistic prayer) one cannot but be struck by the way theological terms are laid upon theological terms in the description of who God is:

“You are without beginning, invisible, incomprehensible, beyond words, unchangeable. You are the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who is the great God and Savior of our hope, the image of Your goodness, the true seal of revealing in Himself You, the Father. He is the living Word, the true God, eternal wisdom, life, sanctification, power, and the true light.”

This tells us that Orthodoxy has no problem with cataphatic theology. Cataphatic theology is integral to Orthodoxy. I can understand why Pastor Cooper described Orthodoxy in this way, but it is simplistic and misleading. I suspect that his understanding of Orthodoxy comes primarily from reading books about Orthodoxy, rather than witnessing real-life Orthodoxy.

The real difference in theological method between Orthodoxy and Protestantism is threefold. The first major difference is that for Orthodoxy doctrine is something received, that is, passed down from generation to generation through the Church going back to the Apostles. In contrast, in Protestantism doctrine is based upon individual inductive reasoning with the biblical texts. Granted, individual Protestant theologians will often consult the Church Fathers. Yet the Holy Tradition of the Fathers have no prior claim but are merely advisory, and thus subordinate to his conclusions, either individually or in committee. The root source of this theological method is sola scriptura—a doctrine with no precedent in the early Church. None of the early Church Fathers opposed Scripture against Tradition, giving priority to Scripture over Tradition. The major Protestant confessions of the 1500s and 1600s were the result of the sharpest minds of a denomination coming together and hashing out their group’s statement of faith. This gives Protestant theology a humanly constructed or self-made nature. While the Reformers did not totally reject the idea of tradition and respected the early Church Fathers, they nevertheless subordinated these to the principle of sola scriptura. In many instances they set aside the Church Fathers for what they considered a “more” biblical teaching.

This new way of doing theology led to a parting of ways from the ancient patristic theology and been at the root of Protestantism’s fragmentation for over 500 years. Rather than promoting unity, there has been a progressive splintering of Protestantism into several thousand separate individual denominations. One of the earliest failures of Protestant theology was the Marburg Colloquy in 1529 between Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli. Here were two Reformers deeply committed to sola scriptura but differed on the meaning of Scripture. Luther believed in the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist while Zwingli believed that the Lord’s Supper was symbolic. They were unable to reach an agreement and went their separate ways resulting in one of the earliest denominational splits in Protestantism. Luther felt so strongly about his difference with Zwingli over the significance of the Lord’s Supper that he wrote:

Before I would have mere wine with the fanatics, I would rather receive sheer blood with the pope.

Father Josiah Trenham, author of Rock and Sand, gave a trenchant analysis of Protestant theology’s basic flaws:

By cutting the cords of Holy Tradition, and placing in its stead the doctrine of sola scriptura, the Protestants ensured theological divisiveness and fracture between themselves and their descendants and have only multiplied divisions, theories, and interpretations ad infinitum, with no end in view to this day. We may judge a tree by its fruit. The sola scriptura tree has borne the fruit of division and every conceivable heresy. (p. 275)

It is puzzling that Pastor Jordan Cooper did not bring up sola scriptura. One could say that sola scriptura is the crown jewel of Protestant theology and ought to be highlighted in any Protestant-Orthodox dialogue. Sola scriptura must not be overlooked, because it is foundational to Protestantism’s theology. Moreover, it has severed Protestantism from the patristic consensus and from the Ecumenical Councils, both of which are foundational to Orthodoxy. While Protestants have cited the Ecumenical Councils, they cannot claim to be in fellowship with the historic Church that gave us the Seven Ecumenical Councils.

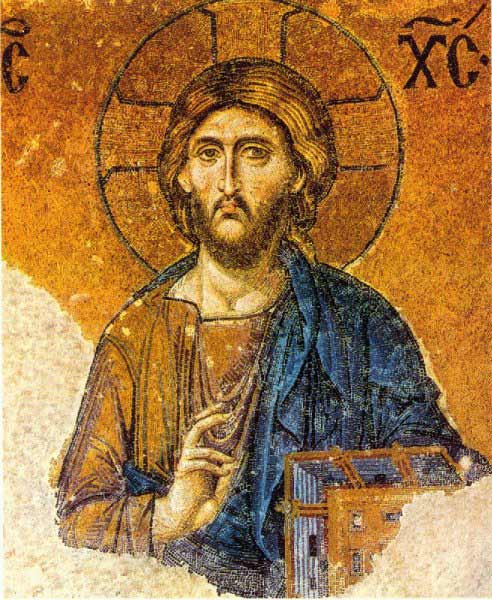

The second major difference is that the Orthodox theology is liturgical theology. Theology books and statements of faith play a secondary in Orthodoxy. My journey to Orthodoxy did not really begin until I began attending on a regular basis an all-English Liturgy. It was after several months that I began to understand the Orthodox theological paradigm and more importantly dimly perceive the spiritual reality referred to in the Liturgy. In the Liturgy I began to sense the reality of God as Trinity in a way I had not in all the years I was a Protestant. As a Protestant I did indeed learn about God as Trinity, however, the Protestant teaching on the Trinity struck me as a convoluted abstraction. Orthodoxy does not attempt to explain the Trinity, but rather it invites the whole human person to be at the Liturgy, to participate in and experience the heavenly worship of the Trinity in all its fullness. This way of expressing and understanding doctrine reflects the ancient theological principle lex orandi, lex credendi (the rule of prayer is the rule of faith).

The third major difference is that Orthodoxy has a twofold approach to knowing God. One way is through the intellectual study of Scripture and the Church Fathers. The other way is through prayer. One of the early Desert Fathers, Evagrius of Pontus, taught: “He who prays is a theologian and he who is a theologian truly prays.” This maxim points to the belief that one can go beyond understanding concepts about God to a personal knowledge of God. In other words, cataphatic theology should lead to apophatic theology. Both go together; just as the human person, the created Imago Dei, cannot be reduced to mere intellect — but is a unity of body, soul and spirit. This latter way of doing theology—spiritual ascent via prayer—ultimately depends upon divine grace and mercy.

Pastor Cooper has set up a false dichotomy when he contrasts the Eastern theology without words against the Western theology by analogy. He notes that in the Western God is known through analogy (2:27). In this method God’s love is likened to human love but far greater. He cites Martin Luther who said if you want to know what God is like look at the babe in the manger. The weakness of theology by analogy is its implicit denial of direct knowledge of God. Ultimately, will we only know about God’s love or will we truly know God who loves us? The goal of Orthodox spirituality is union with Christ and life in the Trinity (John 17:21-23). Protestantism’s rejection of apophatic theology has led to a rejection of contemplative prayer. In Protestantism prayer is understood primarily as petition (asking God for things) than as union with God. This has had a limiting effect on Protestant spirituality. Theology by negation is an important part of Orthodoxy, but it does not represent the totality of Orthodoxy. Orthodoxy prays with words and without words. In Orthodoxy theology without words refers to experiencing God through prayer. Prayer without words can be viewed as the more advanced form of prayer.

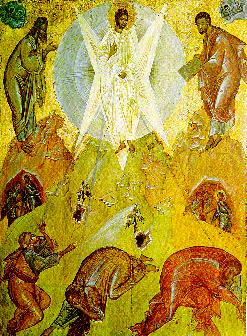

Objection 2 — Theosis

The second reason Jordan Cooper gives is the Neo-Platonism underlying Orthodoxy’s doctrine of theosis (4:03, 4:44). He points to Pseudo-Dionysius, the Palamite tradition, and the twentieth century theologian Vladimir Lossky as evidence. I have heard this criticism before, but this criticism to me seems based more on assertions than on evidence-based arguments. I invite Pastor Jordan Cooper or other Protestants to show me the evidence. Then I would ask them to explain how Neo-Platonism is so inimical to the Christian Faith.

Furthermore, Pastor Cooper needs to wrestle with the fact that Augustine of Hippo taught the doctrine of theosis. In my article “Theosis and Our Salvation in Christ,” I cite an excerpt from Augustine’s exposition on Psalm 50. In it he notes that we are deified by grace, not by nature, which is what Orthodoxy teaches.

See in the same Psalm those to whom he says, “I have said, You are gods, and children of the Highest all; but you shall die like men, and fall like one of the princes.” It is evident then, that He has called men gods, that are deified of His Grace, not born of His Substance. For He does justify, who is just through His own self, and not of another; and He does deify who is God through Himself, not by the partaking of another. But He that justifies does Himself deify, in that by justifying He does make sons of God. “For He has given them power to become the sons of God.” (John 1:12) If we have been made sons of God, we have also been made gods: but this is the effect of Grace adopting, not of nature generating. (Augustine Exposition on Psalm 50; emphasis added)

This is not a one-time exception. Augustine also affirmed theosis at least two times in his City of God. In this passage he explains how God intended Adam to achieve theosis through reliance on divine grace, not on proud self-reliance.

For created gods are gods not by virtue of what is in themselves, but by a participation of the true God. (Book 14.13; emphases added; see also NPNF Vol. 2 p. 274)

In the conclusion of City of God, Augustine affirms that theosis takes place through union with Christ.

There shall we be still, and know that He is God; that He is that which we ourselves aspired to be when we fell away from Him, and listened to the voice of the seducer,

You shall be as gods,(Genesis 3:5) and so abandoned God, who would have made us as gods, not by deserting Him, but by participating in Him. (Book 22.30; emphasis added; see also NPNF Vol. 2 p. 511)

This leaves me wondering whether Pastor Cooper is going to criticize his favorite theologian of Neo-Platonism and of having a defective soteriology? I would suggest that Augustine’s affirmation of theosis points to theosis as common ground between Western Christianity and Orthodoxy.

Pastor Cooper points out that the New Testament places the emphasis on the finished work of Christ, whereas the Orthodox Church does not (3:23). I am not sure on what he makes this claim. If one listens attentively to the Divine Liturgy one learns much about how God works in history to bring about our salvation in Christ. Every Sunday the Liturgy recounts the Incarnation, Christ’s saving death on the Cross, and his victorious third day Resurrection. What the Liturgy does is sum up the biblical narrative of salvation history. I suspect that when he speaks of the “finished work of Christ” he is using a Protestant theological code, that it is because of Jesus’ atoning death on the Cross we who believe in him have been forgiven and our legal status has changed from that of condemned criminals to children legally entitled to the benefits of God’s kingdom. This approach to soteriology narrows the focus to Christ’s death on the Cross, leading to an under appreciation of Christ’s Incarnation and his Resurrection. We are saved by the Person of Christ, not by just one thing He did. It was not until I encountered Orthodoxy that the pieces of the puzzle came together, enabling me to get a glimpse of a more complete picture. It troubles me that Pastor Cooper is implying this sixteenth century theological paradigm is superior to the soteriology presented in the ancient liturgies.

Objection 3 – The Doctrine of Justification

Pastor Jordan Cooper identifies the doctrine of justification as the major reason why he is not Orthodox. He points out that in the New Testament there is much legal language surrounding justification: acquittal, condemnation, judgment, all of which are courtroom language (7:41). He notes that this emphasis is lacking in Orthodoxy. Cooper asserts that Orthodoxy’s anti-Western prejudice leads away from the forensic language of the New Testament (9:24). My response: There is indeed forensic language in Scripture. However, it is important to keep in mind that Scripture contains a multitude of different ways of describing and explaining salvation in Christ: redemptive, imitative, transformative, covenantal, etc. Moreover, the Protestant reading of Scripture gives greater attention to the Apostle Paul, whereas in the Orthodox reading of Scripture greater priority is given to the Gospels. This is especially evident in the Scripture reading in the Liturgy. What troubles me is that the Protestant doctrine of sola fide, a theological novelty invented by Martin Luther in the 1500s, was never a part of the ancient patristic consensus. By turning sola fide into a dogma and a theological plumb line by which to assess the orthodoxy of other theological traditions Protestantism has become doctrinally schismatic. See my article “Response to Theodore – Semi-Pelagianism, Sola Fide, and Theosis.”

Pastor Cooper notes that there is a need for greater balance between Orthodoxy’s participatory language and the biblical forensic language (8:04). I would point out that Orthodoxy’s theology is fundamentally liturgical, not scholastic. What we believe can be found primarily in the fifth century Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom and the fourth century Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great. The Orthodox priest is using forensic language when he says “for the remission of sins” over the bread and over the wine. I would ask Pastor Cooper: “Are you saying that the theology in these early liturgies is imbalanced and theologically deficient? Would it not be the case that you are using your Euro-centric, post-1500s theology as the theological norm by which to assess all other theological systems and find them wanting?”

Objection 4 – The Augustinian Theological Tradition

Pastor Cooper expressed his dismay at the anti-Western prejudice by certain Orthodox theologians. This anti-Western bigotry is to be deplored as small-minded and not characteristic of the true spirit of Orthodoxy. Orthodoxy is not Eastern; it is catholic in the sense of embracing and constituting the whole. Orthodox theology is catholic in scope embracing both East and West. It is the universal Faith for all nations. There is a need for Orthodoxy to better integrate the Latin Fathers with the Greek Fathers. The way has been opened by the Western Rite Liturgy and Orthodox Western Rite vicariates. It would be good if Orthodox seminaries offered classes on the Latin Fathers.

At the 12:15 mark, Jordan Cooper states that the Fall is clearly taught in the New Testament. I have no disagreement with that, but what I would question is whether the New Testament depicts the Fall as a catastrophic event as understood by Augustine. Unless there is indisputable textual evidence for a catastrophic Fall, what we have here is an interpretation, not a fact. In light of the fact that there are other interpretations of the Fall, it would help if Protestants were less dogmatic in their soteriology. Could Pastor Cooper please give us the chapter and verse that explicitly teaches that the Fall was such a catastrophic event that resulted in humanity becoming a massa damnata (condemned mass) and as a result of inherited guilt an infant was eternally damned at birth? These are conclusions resulting from rigorously applying logic to certain theological premises. There is a certain attractiveness to Protestant theology’s quest to be logical and internally consistent; however, the results can be invalid and even harmful if the initial premises are faulty.

Pastor Cooper notes Orthodoxy’s less severe understanding of the Fall leads to greater emphasis on synergy. In contrast, the Western Augustinian tradition catastrophic understanding of the Fall leads it to give greater emphasis on divine grace in our salvation. However, it should be noted that what Cooper is doing here is doing theology on the basis of one Church Father while ignoring the patristic consensus. Pastor Cooper needs to beware of building his theology around one particular Church Father. To focus on just one Church Father is to risk theological sectarianism. The way to avoid this error is to embrace the patristic consensus, to faithfully read one Church Father against the broader context of the other Fathers. We should bear in mind the Apostle Paul’s rebuke to the Christians in Corinth for their factionalism when they claimed: “I am of Paul,” or “I am of Apollos,” or “I am of Cephas,” or “I am of Christ.” (1 Corinthians 1:12; NKJV) In light of the fact that there is no patristic consensus regarding the consequence of the Fall, we ought to be refraining from turning our particular interpretation into a universal dogma. My view is that there is room for disagreement between the Augustinian and other understandings within Orthodoxy.

Augustine was not the only Latin Church Father. There was Ambrose of Milan, who brought Augustine to faith in Christ and who made use of Eastern melodies in the hymns he composed. The Western tradition includes Vincent of Lerins, Leo of Rome, Pope Gregory (aka Gregory the Great), Jerome, and Cyprian of Carthage. Going back to the time of the Apostolic Fathers, there was Clement of Rome and Irenaeus of Lyons, who, although they wrote in Greek, can be considered part of the Western tradition. To be fair, Pastor Cooper did mention Prosper of Aquitaine and Ambrose of Milan (11:58). In terms of spirituality, the Western Christian tradition can lay claim to Benedict of Nursia. These are saints recognized and venerated by the Orthodox Church. Thus, the Western tradition is far more diverse and richer than Pastor Jordan Cooper has led us to believe.

Augustine’s preeminence in Western theology is largely due to historical circumstances. With the Fall of Rome in the fifth century, Western Europe became isolated from the spiritual heritage of the Byzantine Empire which would continue the Roman Empire for another thousand years. During the Middle Ages, Scholasticism used Augustine’s writings as the basis for their theological project. It is from this theological framework that Protestantism would emerge. As a result of this historical circumstance, Protestant theologians by and large regard the early Church Fathers as exotic theological resources, not as foundational sources of theology.

The main problem here is not so much Augustine, but rather those who have turned their interpretations of Augustine’s teachings into fundamental dogmas of the Christian Faith. Would Augustine have agreed with them and become Protestant? Western Christians err when they elevate to the level of dogma Augustine’s catastrophic understanding of the Fall, his forensic understanding of Original Sin, his forensic understanding of justification, and his teaching of the double-procession of the Holy Spirit. All these should be regarded as theological options within the scope of Holy Tradition. It is dangerous to the unity of the Faith if one were to utilize Augustine as the theological plumb line for Christian theology. That function belongs more properly with the Ecumenical Councils and with the patristic consensus.

There is considerable value in the Western tradition. For example, in the OrthodoxBridge blog site I frequently refer to the theological principle lex orandi, lex credendi (the rule of prayer is the rule of faith). This saying, which has been attributed to Prosper of Aquitaine, has helped me to view the ancient liturgies as having something akin to dogmatic authority in doing theology. It also helped me to understand that when a theological tradition modifies its way of worship, its beliefs will likewise undergo a shift. Another Western principle I have found so helpful is the Vincentian Canon:

Quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est. (That Faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all) The Commonitory (ch. 2) Vincent of Lérins

In my journey to Orthodoxy I found the Vincentian Canon useful for assessing the validity of Protestant teachings like the rapture, pre-millennialism, the born again experience, the Lord’s Supper as purely symbolic, and even the more foundational doctrines like sola fide (faith alone) and sola scriptura (Scripture alone). The Vincentian Canon helped me to make sense of the overwhelmingly massive corpus of early Church writings. The Orthodox Church is not as anti-Western as Pastor Jordan Cooper makes it out to be. It should be noted that during Great Lent the Orthodox Church uses the Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts, a liturgy that has been attributed to Pope Gregory the Great. I would challenge Pastor Cooper and other Protestant pastors to tell us what ancient Western liturgies they use today.

Pastor Jordan Cooper notes that he is indebted to Augustine for his understanding of the Trinity, especially as presented in De Trinitate (10:05). One of Augustine’s controversial contributions to theology is his teaching on the double procession of the Holy Spirit. Many Orthodox Christians vehemently reject this teaching. My stance is more tempered. I regard Augustine’s double procession of the Holy Spirit something that falls into the category of adiaphora—not an essential doctrine. In my opinion it is a tolerable theological option so long as it is not imposed upon the Nicene Creed promulgated at the Second Ecumenical Council in 381. Kallistos Ware noted in The Orthodox Church (1997):

For all these reasons there is today a school of Orthodox theologians who believe that the divergence between east and west over the Filioque, while by no means unimportant, is not as fundamental as Lossky and his disciples maintain (p. 218).

Prior to my becoming Orthodox, I was Western in my theology. I did hold Augustine of Hippo in high regard having read his Confessions, City of God (De Civitate Dei), and The Trinity (De Trinitate). However, I was more committed to John Calvin. A critical part of my journey to Orthodoxy consisted in the critiquing of John Calvin and other Reformed theologians. I did not so much reject Augustine as I moved away from Protestant Augustinianism. What Pastor Cooper referred to as Augustinian theology is really Protestant Augustinianism—the result of the Reformers cherry picking Saint Augustine. As I became acquainted with the ancient liturgies and the broad patristic consensus I became aware of other theological positions besides Augustine.

One of the knotty problems in Protestant theology is Hell and the Final Judgment. The strong need to be logical in their theologizing has led Western Christians to some rather unpleasant conclusions, e.g., unbaptized infants being condemned to Hell, the millions of people who have had no exposure to the Christian message likewise being condemned to Hell, and those who grew up in a loving Christian family going to Hell because they are not part of the predestined elect. In reaction there arose some questionable theological alternatives, e.g., the teaching that everyone will go heaven (universalism) or the suffering in Hell will not be eternal as the condemned ones will eventually be annihilated (annihlationism). What I found appealing about Orthodox soteriology is its bold confidence in Christ’s Resurrection, its humble uncertainty about the eternal destiny of individuals, and its emphasis on our calling to participation in the life of the Trinity over attaining legal/moral perfection. I found myself drawn to the teaching that the suffering of Hell is the suffering of rejecting God’s love. God does not send people to Hell as they choose to live apart from God. People end up in Hell as a result of their free choice. This paradigm avoids the two extremes of Western eschatology: (1) Hell as a torture chamber for the non-elect and (2) Heaven as a place where everyone ends up regardless of their free choice. See Alexandre Kalomiros’ “River of Fire.”

I would say that one can convert to Orthodoxy and still hold on to Augustine of Hippo. However, this love of Augustine must be balanced by the recognition that the patristic consensus and the Ecumenical Councils take priority over any single theologian. Furthermore, any convert to Orthodoxy must guard against being contentious in commending Augustine to others. Likewise, I would urge Orthodox Christians to treat Western converts with charity and humility. Let me reiterate: Anti-Western bigotry is contrary to Orthodoxy’s catholicity. There is value in the Western patristic tradition. The goal on both sides must be to deepen and enrich Orthodoxy’s catholicity. Orthodoxy needs to be receptive to enriching our understanding of the patristic consensus if we are to effectively reach out to Western Christians.

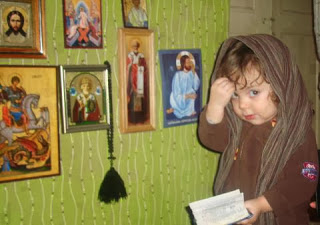

Objection 5 – Orthodox Icons

Jordan Cooper’s fifth reason for not becoming Orthodox is the central role played by images (icons) in Orthodox worship and spirituality (12:23, 13:35). First, no Orthodox Christian would say that icons are the focus of the Liturgy. The central focus of the Liturgy is the Eucharist in which the faithful receive Christ’s body and blood. Second, icons do not play a central role in Orthodox spirituality. If anything, it is the Jesus Prayer—“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, the sinner”—that is given prominence in Orthodox spirituality.

I suspect that Pastor Cooper was overwhelmed and distracted by the visual prominence of icons in Orthodox churches which led him to make this sincere but off-based criticism. Initial reactions to a new and unfamiliar presence of icons in Orthodox churches and homes do not mean a Protestant visitor rightly grasped the role and significance Icons play in the life of Orthodoxy. Indeed, misunderstanding is quite common. This is why it is so important for those who are curious about Orthodoxy or who wish to critique Orthodoxy to attend numerous Orthodox liturgies. It is also important that they talk with the local priest. Without engaging the priest in dialogue there is the danger of prejudging or misinterpreting Orthodoxy. Protestants visiting Orthodox church services are often like monocultural American tourists who travel abroad to strange exotic cultures, take a few pictures, buy a few souvenirs, then come home thinking themselves experts on the culture they just visited. It is one thing to have icons on one’s bookshelf, it is another thing to have a prayer corner with icons. Icons are meant to be aids to prayer.

Pastor Cooper notes that the early Church did not seem to have the strong view of images as necessary (14:01). This strikes me as taking a primitivist approach to the early Church like the nineteenth century frontier Restorationist movement. Orthodoxy is not about theological primitivism, but rather the faithful transmission of Apostolic Tradition. Where Pastor Cooper seems to have a static understanding of Apostolic Tradition, Orthodoxy has a dynamic understanding. This dynamic understanding of Tradition is based on Jesus’ promise that the Holy Spirit would guide His Church into all truth (John 16:13). It is thanks to the Ecumenical Councils that we have the term “Trinity” and the mature Christology that explicitly affirmed Christ’s divinity and his two natures in one Person. From a primitivist standpoint these are extra-biblical novelties, but for Orthodoxy these represent the flowering of Apostolic Tradition. So likewise the Seventh Ecumenical Council’s affirmation of the veneration of icons represents the further development of the Christian Faith. These are not theological options but rather the consensus of the early Church. To reject the authority of the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II, 787) would be to weaken one’s respect for the authority of the earlier Ecumenical Councils. One cannot pick and choose among the Ecumenical Councils. Doing so would entail denigrating the authority of the early Church, rejecting the ancient Christian Faith and embracing instead a novel, modern theological framework, which is what Protestantism is.

Conclusion

In many instances Pastor Cooper’s reasons for not becoming Orthodox can be traced to a superficial understanding of Orthodoxy. It is evident that he has done quite a bit of reading on Orthodoxy; however, this puts him at the beginning stage of understanding Orthodoxy. Even if he has read Lossky and other prominent theologians, one cannot read one’s way into Orthodoxy. The better way is through attending Orthodoxy’s Divine Liturgy and talking one-on-one with a priest. With respect to Pastor Cooper’s commitment to Augustine, I would say that there is room for Saint Augustine in Orthodoxy, but not for dogmatic Augustinianism. Central to Orthodox theology is the consensus of the Church Fathers, the Ecumenical Councils, and the liturgies of the Church. If Pastor Jordan Cooper wishes to object to Orthodoxy, he will eventually have to explain why he is rejecting the patristic consensus for one Church Father. Pastor Cooper needs to wrestle with the fact that his Augustinianism is regional (Western Europe) in terms of geography, Medieval in terms of historical roots, and reflects the cultural values of one particular region (Western Europe). Therefore, Protestant theology cannot lay claim to catholicity. In Orthodoxy’s patristic consensus is a theological tradition that is far richer, older, and wiser than Protestant Augustinianism. In Orthodoxy’s spiritual tradition is the promise of genuine transformation (theosis) and direct knowledge of God through union with Christ. This promise of transformation can be seen in the lives of the saints. Pastor Jordan Cooper may point to various Protestant theologians and their books, but I will point to the Orthodox saints like Saint Mary of Egypt, a repentant sex addict who devoted the rest of her life to prayer and fasting in the desert; Saint Xenia of Petersburg, who lived a carefree life until her husband’s unexpected passing then lived the rest of her life as a holy fool; and Wonder Working Saint John of Shanghai and San Francisco, who in addition to his miracles, is known for his welcoming of the Western saints into Orthodoxy.

Robert Arakaki

Resources

Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese. “Western Rite.”

Robert Arakaki. “Orthodox Christians on Penal Substitutionary Atonement.”

Robert Arakaki. “Contra Sola Scriptura (4 of 4): Protestantism’s Fatal Genetic Flaw: Sola Scriptura and Protestantism’s Hermeneutical Chaos.”

Robert Arakaki. “Contra Sola Scriptura (3 of 4): Where Does Sola Scriptura Come From? The Humanist Origins of the Protestant Reformation.”

Robert Arakaki. “Response to Theodore — Semi-Pelagianism, Sola Fide, and Theosis.”

Robert Arakaki. “Theosis and Our Salvation in Christ.”

Augustine of Hippo. Confessions. Loeb Classical Library.

Augustine of Hippo. City of God.

Augustine of Hippo. The Trinity.

Peter Brown. Augustine of Hippo: A Biography.

Pastor Jordan Cooper. “Five Reasons I Am Not Eastern Orthodox.”

Alexandre Kalomiros. “River of Fire.”

Vladimir Lossky. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church.

Josiah Trenham. Rock and Sand.

Kallistos (Timothy) Ware. The Orthodox Church. (1997 edition)

Vincent of Lerins. Commonitory 2.

Recent Comments