Folks,

I recently received a comment from David Jones, an Orthodox Christian, who has been in conversation with a Reformed pastor about my paper on the Reformed doctrine of predestination. Below are my responses.

Robert

David,

I’m glad to hear of your conversation with your Reformed/Calvinist pastor friend. It is good to see bridges being built across two different theological traditions.

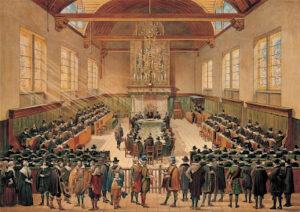

My assumption here is that your friend is responding to my paper: “Plucking the TULIP: An Eastern Orthodox Critique of the Reformed Doctrine of Predestination.” First, I was amused and a little exasperated by your friend’s allegation that I made “broad sweeping arguments about predestination without an apparent understanding of Reformed theology.” I took care to provide quotes from the Synod of Dort, the Westminster Confession and from Calvin’s Institutes in “Plucking the TULIP.” I think your friend is confusing understanding with agreement. One can understand a doctrine without necessarily agreeing with it. If one denies that possibility, then interfaith dialogue becomes an impossibility. He cannot simply claim that I lack understanding of Reformed theology without offering some evidence to show where and how I misunderstood Reformed theology. Not to do so is intellectually irresponsible. Ask your friend: Please show me where the author is wrong or misunderstood his sources.

Second, I became confused at times by your friend’s criticisms and rebuttals. It appears as if he is responding to multiple critiques of Reformed theology at the same time and in the process he has me confused with others. I get the impression that he is writing more in the heat of passion than from a calm and reasoned reflection. While there are many critiques and challenges to Reformed theology, I presented my own critique of the Reformed doctrine of predestination. I would expect him to engage me with respect to my arguments and my sources. Having me confused with others is a waste of time for me and for him.

Theological Methods

Your friend wrote:

1. He spends a great deal of time discussing Augustine’s influence on the Reformed tradition without addressing Christ’s and Paul’s parallels with Augustine.

There is a strategy behind my numerous quotations from the early church fathers. My theological methodology is grounded in historical theology. I am trying to demonstrate the theological consensus in the early church. Furthermore, I am trying to show that my theological positions are rooted in the consensus of the early fathers and that your friend’s theological framework is at odds with the theology of the early church. Much of his approach to theology, especially his concern for the systematic ordering theological propositions, reflects medieval scholasticism.

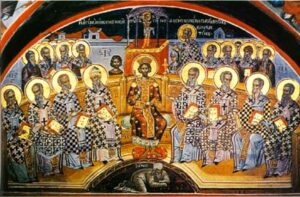

From the standpoint of historical theology, Augustine is just one church father among many. If your friend wants to argue that Augustine of Hippo was the preeminent theologian of the early church he will have to make his case. Furthermore, your friend’s assertion that the teachings of Christ and Paul paralleled that of Augustine seems to privilege Augustine over the other major church fathers. This was not the case with the Byzantine East. I would argue (with the thousands of bishops who attended Church Councils) that there were other early church fathers whose teachings paralleled Christ and Paul.

One thing that struck me as I read your friend’s apologia for Reformed theology was how ahistorical it is, and how dependent it is on Cartesian logic. One of the weaknesses of Cartesian logic is the unquestioned acceptance of fundamental premises of an argument. Another weakness is that it assumes that internal consistency and the absence of contradictions are the marks of superior doctrine. Unlike medieval Scholasticism, which attempted to turn theology into a science utilizing human reason, the early church sought to be faithful to the doctrines received from the Apostles. A study of their argumentation regarding the Trinity, Christology, ecclesiology, the Real Presence in the Eucharist, and the sacraments will show that they were not bound by the strict demands of Cartesian logic.

A friend of mine, a Reformed Christian transitioning to Orthodoxy, wrote this about the role of Cartesian logic in doing theology:

The big difference between the two systems can be seen in how they respond to the charges of being “illogical.” The Calvinist first chooses to abide in the world of Cartesian logic — but then denies the unhappy necessities of that world when it rubs against him.

The Orthodox never concedes to this world of logical necessity. God’s Sovereignty over all things is not threatened by Man’s free will. Nor is man’s free-reception of God’s saving Grace in any way seen as merit or righteousness in Man. The Calvinists thus denies the logic of the world he has created…while the Orthodox never grants the world of Logic its a priori existence.

Ultimately, I like the way the Fathers and Church have dealt with their supposed “problems” far better than the way Calvinist are forced to deny the logical necessity of the world they’ve chosen to live in.

R.C. Sproul on Double Predestination

You wrote:

I know you have heard all this before. But we keep coming back to the same debate. So, I’ve attached a brief but great article by R.C. Sproul delineating what the Reformed doctrine actually teaches. Note his point. (1) God DOES positively elect sinners to salvation; (2) God DOES NOT positively elect the reprobate to condemnation (that is He does not inculcate sin; it’s already in all of us). But, that he elects some and NOT others must mean that by his sovereign will He CHOOSES to leave them in sin. We are saved by God and condemned by our own sin nature.

The doctrine of double predestination has generated much controversy and criticism. Some have criticized it as being morally repugnant, labeling it a “horrible decree.” R.C. Sproul in “Double Predestination” critiqued the symmetrical understanding of double predestination arguing that while God is the author of our salvation, his passivity with respect to the reprobate does not make him the author of our sins. The problem here is that nowhere did I allege that this doctrine is flawed because it makes God the author of our sins. Here your friend is muddying the waters by rebutting something I never said.

R.C. Sproul’s defense of double predestination focuses on reprobation, but in “Plucking the TULIP” I noted that one of the fundamental problems in the Reformed doctrine of double predestination lies in their doctrine of election and the irresistible nature of God’s grace. As Kallistos Ware noted, where there is compulsion there is no love. This means that if love is based on free will then logically speaking, irresistible grace because it involves compulsion denies the possibility of genuine love. I added in my paper that the denial of free will also leads to the denial of genuine faith. This means that the Reformed doctrine of election undercuts the ontological basis for love and faith. As distasteful as the Reformed doctrine of reprobation may be, it is the doctrine of election implemented via irresistible grace that they should be defending. I’m puzzled over your friend’s silence on this. Furthermore, I am also puzzled by your friend’s silence over the troubling implications that irresistible grace has for the doctrine of the Trinity which I sketched out in my essay.

Romans 8:28 and Synergy

Your friend wrote:

Foreknowledge is “preknowledge” nothing is destined, only foreknown. If this is truly biblical than what hope is there in Romans 8:28? How does God work all things for the good for those who love him, if He is not a causal agent?

I’m sure your pastor friend knows how to read the New Testament in Greek. It bothers me that his paraphrase of Romans 8:28 mistranslates “συνεργει” (sunergei) which means to “work with.” Your friend seems to imply that God is the sole causal agent, but Paul is teaching synergy—how all things work together for those who love Him. The word “θεον” (“God” in the accusative case) here is the recipient of the participle “τοις

αγαπωσιν” (the ones who love ____ ). God here is not the causal agent; if he was then the word “θεον” would take the nominative form “θεος.” The word “συνεργει” (work together) is preceded by “παντα” which takes the nominative form; thus the phrase “παντα συνεργει” is best understood to mean “all things work together.” Please ask your Reformed friend if there is anything wrong with my reading of the Greek text for Romans 8:28.

Intrinsic Righteousness Versus Extrinsic Righteousness

Your friend wrote:

2. If it is Free Will: What is your intrinsic righteousness? If you argue the merit of Free Will you must recognize that you have an intrinsic righteousness within you. If one chose correctly one chose righteously.

3. When you enter heaven what portion, as small as it may be, do you give for your RIGHT to be there? If you argue on the basis of Free Will there must logically be an answer. An inherit righteousness within self chose love and God.

My problem here is that the term “intrinsic righteousness” and the concomitant “extrinsic righteousness” are not found in Scripture. They were coined by Reformers to refute Roman Catholic theologians whose doctrines were based on a merit based soteriology. I therefore decline to respond to his questions on the grounds that to answer his questions using his terminology assumes agreement with certain presuppositions, e.g., that salvation equals entrance into heaven or that salvation is based on legal merit. The fundamental problem here is that the way your friend phrased his questions is rooted in the theological framework of medieval Catholicism and is alien to the way theology was done historically. The narrowness and provincialism of late medieval Catholic soteriology and Luther’s sola fide violates the Vincentian Canon: “that which has been believed everywhere, always, and by all.” I would be more than happy to answer your friend’s questions providing that he can show that the questions are compatible with the theological framework of the early church fathers or the Ecumenical Councils.

Your pastor friend insinuated that I believe that God will save us by our merit:

The author of your article often used quotes stating that God does not use compulsion or coercion. He is a gentleman, who patiently waits to reward our small merit which enables us to choose him by free will while we are “children of wrath,” “enslaved to sin,” “ “lovers of darkness,” “dead in our iniquity,” “at enmity with God” etc, etc, etc.

A careful reading of my “Plucking the TULIP” paper will show that I avoided asserting that God will reward our merit. Here your friend is putting words in my mouth which I strongly object to. This is intellectually irresponsible and morally objectionable. If I am mistaken then it is incumbent on your friend to provide a quote from my paper or reference the page number.

It seems to be a widespread Protestantism notion, born of their reaction to Roman Catholicism, that any and all “free-will” actions by man in receiving the gift of salvation (or any grace from God) is by definition “meritorious” – earning of God’s favor, and a “good work” that man adds to the work of Christ. But such notions and regard for human actions are altogether foreign to the theological history of the Church for at least the first 1200 years. Helpless humanity no more merits the grace of salvation by receiving Christ – than a helpless soul dying of thirst in the desert “merits” life by his “good work” of drinking water brought and mercifully offered to him while dying. This extreme understanding of grace arose out of the unique historical circumstances in the 1500s, and thus is an idiosyncratic reaction to medieval Roman Catholicism. These peculiar Protestant notions are at odds with the historic Christian Faith. If your friend disagrees with this all he needs to do is provide evidence showing that the Protestant exclusion of any meritorious act in our salvation was part of the broad theological consensus and was the doctrine of the undivided church of the first millennium.

Historical Context for Romans 9

You Reformed friend wrote:

If Paul, in Romans 9 is not talking about predestination in the Reformed sense, which many criticize as unfair, unloving, crass etc. Then why does Paul anticipate so many objections to his argument? Perhaps it would be better to phrase it this way. If Paul is arguing an Arminian/Molinist view of soteriology than why in the world would there be any objections at all!!! If by our free will we can either choose God or not and suffer the just consequence of either choice – where is the objection?

Just because I disagree with Reformed theology does not automatically mean that I agree with the Arminian soteriology. Here your friend is engaging in the hasty generalization fallacy. If he believes that my soteriology is similar to that of the Arminian/Molinist view then he should carry out a comparison between the two. Here he is being intellectually lazy.

It is clear to anyone reading Romans that Paul was seeking to address a theological controversy when he wrote Romans. The question then becomes: What were the issues underlying this controversy? Your friend like many of the early Reformers assumed that Paul’s opponents, the Judaizers and first century Pharisees, had an understanding of salvation, similar to that of medieval Catholics, that is, one needed to acquire spiritual merit in order to receive divine approval. But there is no historical evidence to support this assumption. Theological and historical scholarship has found that Paul’s controversy with the Judaizers revolved around whether faith in Christ necessitated adherence to Jewish Law and being a Jew. Thus, “works” in Romans referred to the mitzvah (good deeds) expected of Jews. From this perspective, salvation in Christ was no longer for the Jews only, and for those who converted to Judaism, but for all who put their faith in Jesus as the Messiah without the obligation to undergo circumcision or keep the Jewish Torah. Faith in Christ did not absolve the Christian to live a life of obedience to God and charity to others (good works). Good works become a sign of a genuine faith in Christ (James 2:26). A careful reading of James shows the absence of the notion of acquiring spiritual merit. Orthodoxy is concerned about Christian discipleship and the discipline of prayer (good works) because these are signs of spiritual growth. Can one claim to be growing spiritually if there are no good works in one’s life?

Theological Paradigms

The main problem I have with the above paragraph is that it assumes the Reformed vs. Arminian debate is the only way to read Romans 9. Many of the assumptions that your friend has came out of medieval Europe and are alien to first century Judaism. First century Judaism was not concerned with determinism and the role of merit in our salvation. Paul Barnett in Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity wrote:

From the time of the Reformation, Galatians has been seized upon to support the proposition that people are “by grace . . . saved through faith . . . not because of works,” to use the convenient words of contrast found in another letter (Eph 2:8-9). However, to read into Paul the Reformation debates of a millennium and a half later is historically problematic (Barnett 1999:345-346).

I have no problem with the understanding that Luther was battling the works-based or merit-based soteriology of pre-Reformation Catholicism. What I do have problems with is the assumption that Paul’s controversy with the Judaizers paralleled that of Luther’s in the 1500s in medieval Europe. Scholarship has challenged that assumption, especially the school of thought known as, new perspectives on Paul. My question to your friend is this: “Where do you stand with regard to the arguments put forward by the new perspectives school? If you disagree and you hold to the view that strong parallels exist between Paul’s controversy with the Judaizers in first century Asia Minor and Luther’s controversy with medieval Catholicism in sixteenth century Europe then please present the evidence or cite a scholar who has written a rebuttal to the new perspectives school.”

Closing Remarks

As I said earlier, it’s good for friends from different theological traditions discuss important issues like salvation in Christ. Key to a fruitful dialogue is a calm heart, a listening ear, an openness to considering the evidence, critical thinking, and trust that though we now see dimly through a mirror God will lead us into the fullness of truth by his Holy Spirit (John 16:13; ). I wish you and your Reformed pastor friend many more fruitful discussions!

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments