A reader wrote:

I’ve really enjoyed browsing your site. I’m a reformed Christian and have appreciated learning about the Orthodox Church. I do find the church appealing but I believe scripture supports the reformed position. I’ve been reading your plucking the tulip article and was hoping you’d interact with John 6, especially vss 44-59 as I’ve yet to hear a compelling argument in favor of the non reformed view of that passage.

The verse the reader referred to is John 6:44 which reads:

No one can come to Me unless the Father who sent Me draws him: and I will raise him up at the last day. (NKJV, OSB; emphasis added)

οὐδεὶς δύναται ἐλθεῖν πρός με ἐὰν μὴ ὁ πατὴρ ὁ πέμψας με ἑλκύσῃ αὐτόν, κἀγὼ ἀναστήσω αὐτὸν ἐν τῇ ἐσχάτῃ ἡμέρᾳ. (NA28; emphasis added)

Verse 44 has been construed to teach that we are saved against our will. Another way to put it is that our human wills have been irresistibly compelled by God’s eternal decree to receive Christ and so become Christians. Furthermore, any so-called freedom of the will or ability to love God is impossible outside the divine decree. It has been claimed that this verse supports the Reformed doctrine of double predestination, or more precisely the doctrine of effectual calling aka irresistible grace.

In this article I examine how John 6:44 can be approached in ways that allow for non-Reformed readings. Key to this argument will be the multiple meanings for the Greek word for “draw” – ελκω (helko). I will also be looking at non-Reformed readings of John 6:44, the context of John chapter 6, and the context of historical theology to see if the Reformed interpretation of John 6:44 holds up to critical scrutiny.

The Reformed Understanding of John 6:44

The famous nineteenth century preacher, C.H. Spurgeon, tells the story of how he was confronted with an interpretation of John 6:44 based on the literal meaning of ελκω (helko) – “to drag.”

Another person turns around and says with a sneer, “Then do you think that Christ drags men to Himself, seeing that they are unwilling?” I remember meeting once with a man who said to me, “Sir, you preach that Christ takes people by the hair of their heads and drags them to Himself.” I asked him whether he could refer to the date of the sermon wherein I preached that extra-ordinary doctrine, for if he could, I should be very much obliged. However, he could not. But said I, while Christ does not drag people to Himself by the hair of their heads, I believe that He draws them by the heart quite as powerfully as your caricature would suggest.

Mark that in the Father’s drawing there is no compulsion whatever; Christ never compelled any man to come to Him against his will. If a man be unwilling to be saved, Christ does not save him against his will. How, then, does the Holy Spirit draw him? Why, by making him willing. It is true He does not use “moral suasion”; He knows a nearer method of reaching the heart. He goes to the secret fountain of the heart, and He knows how, by some mysterious operation, to turn the will in an opposite direction, so that, as Ralph Erskine (1685-1752) paradoxically puts it, the man is saved “with full consent against his will”; that is, against his old will he is saved. But he is saved with full consent, for he is made willing in the day of God’s power. Do not imagine that any man will go to heaven kicking and struggling all the way against the Hand that draws him. Do not conceive that any man will be plunged in the bath of a Saviour’s blood while he is striving to run away from the Saviour. Oh, no! It is quite true that first of all man is unwilling to be saved. When the Holy Spirit hath put His influence into the heart, the test is fulfilled: “Draw me and I will run after thee” (Song 1:4). We follow on while He draws us, glad to obey the Voice which once we had despised. (source; emphasis added)

Here, Spurgeon’s studiously avoided the literal meaning of ελκω “to drag.” He could have used the more literal meaning of ελκω as when the Apostle Paul was physically dragged in Acts 16:19 and 21:30, but he did not. Insisting that there is no compulsion involved in our salvation, Spurgeon relied on the figurative meaning used in the Song of Songs. He states that there is no “moral suasion” involved (which would have implied Arminianism), and instead insists that it was a “mysterious operation” of the Holy Spirit that brings about conversion.

In contrast to Spurgeon’s figurative understanding, Ligonier Ministries uses the more literal meaning of ελκω found in Acts 16:19:

. . . it is also clear that any position that says the Lord only “woos” us cannot be maintained. The same word translated “draw” in John 6:44 is found in Acts 16:19 and James 2:6 where the apostolic authors speak of someone being “dragged” somewhere. Though the elect may try at first to resist God’s drawing, He drags us, against our fallen wills, to Jesus. God overcomes our natural enmity toward Himself and guarantees that His elect people will choose to follow Christ. (source; emphasis added.)

The tension between two notable Reformed Christians, C.H. Spurgeon and R.C. Sproul’s Ligonier Ministries, on the meaning of ελκω in John 6:44 shows that understanding John 6:44 is not as simple as some may think.

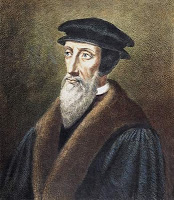

So, where does John Calvin stand with respect to Spurgeon and Ligonier Ministries’ conflicting interpretations? Calvin’s understanding of John 6:44 can be found in his commentary.

Unless the Father draw him. To come to Christ being here used metaphorically for believing, the Evangelist, in order to carry out the metaphor in the apposite clause, says that those persons are drawn whose understandings God enlightens, and whose hearts he bends and forms to the obedience of Christ. The statement amounts to this, that we ought not to wonder if many refuse to embrace the Gospel; because no man will ever of himself be able to come to Christ, but God must first approach him by his Spirit; and hence it follows that all are not drawn, but that God bestows this grace on those whom he has elected. True, indeed, as to the kind of drawing, it is not violent, so as to compel men by external force; but still it is a powerful impulse of the Holy Spirit, which makes men willing who formerly were unwilling and reluctant. It is a false and profane assertion, therefore, that none are drawn but those who are willing to be drawn, as if man made himself obedient to God by his own efforts; for the willingness with which men follow God is what they already have from himself, who has formed their hearts to obey him. (Emphasis added.)

Calvin cites John 6:44 eight times in his Institutes. He understood “draw” in the sense of the mysterious work of the Holy Spirit in the Christian believer.

Hear Him calling, ‘No one comes to me unless my Father draws him’ [John 6:44]. And one may incontrovertibly conclude from John’s words that the hearts of the pious are so effectively governed by God that they follow Him with unwavering intention. (Institutes 2.3.10; p. 304; emphasis added)

Calvin seems to occupy a middle ground between Spurgeon and Ligonier Ministries with respect to God’s efficacious calling. Where Spurgeon sought to soften the repellent connotations of efficacious calling, Ligonier Ministries underscored the coercive nature of divine election insisting that God drags us against our fallen wills. I have been unable to find Calvin using similar stark language which leads me to suspect that Ligonier Ministries may be more Calvinistic than Calvin!

The Reformed understanding of John 6:44 is not the only interpretation. Noted Roman Catholic bible scholar, Raymond Brown, favors understanding our being drawn to Christ in terms of attraction or desire, not compulsion. In his Anchor Bible Commentary on John, Brown notes:

If the Jews will desist from their murmuring, which is indicative of a refusal to believe, and will leave themselves open to God’s movement, He will draw them to Jesus. This is the age spoken of by the prophet Isaiah when they are being taught by God, if only they will listen. This teaching has its external aspect in the sense that it is embodied in Jesus who walks among them, but it is internal in the sense that God acts in their hearts. It is a fulfillment of what Jeremiah xxxi 33 had promised: “I will put my law within them, and on their hearts will write it” (John Bright, The Anchor Bible, vol. 21). This internal moving of the heart by the Father will enable them to believe in the Son and thus possess eternal life. (p. 277; emphasis added)

Brown’s non-Reformed reading can be seen in the causal reasoning: If the Jews will desist from murmuring, then God will draw them to Jesus. This allows for the freedom of choice – to resist God’s grace or to be receptive to God’s grace in Christ by listening to what Jesus has to say.

John Chrysostom, one of the preeminent preachers in the early Church, likewise offers a different approach to John 6:44. He understands ελκω in John 6:44, not in terms of compulsion, but as persuasion or wooing. A Calvinist reading Homily XLVI cannot help but be struck by John Chrysostom’s blunt, explicit affirmation of human free will:

For if a man cometh to Him,” saith some one, “what need is there of drawing?” But the words do not take away our free will, but show that we greatly need assistance. And He implieth not an unwilling comer, but one enjoying much succor (p. 164; emphasis added).

If there are other ways of interpreting John 6:44, the issue then becomes which is the more accurate understanding of the verse?

John 12:32

To better understand the meaning of ελκω in John 6:44, it helps to compare how the word is used in John 12:32. Here we have the same word used in two similar contexts within the same book. Under normal circumstances, we can expect the same meaning to apply for both contexts.

And I, if I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all peoples to Myself. (NKJV, OSB)

κἀγὼ ἐὰν ὑψωθῶ ἐκ τῆς γῆς, πάντας ἑλκύσω πρὸς ἐμαυτόν. (NA28; emphasis added.)

However, the Reformed folks’ attempt to apply the literal meaning of ελκω as compulsion has problematic implications, i.e., universalism, that all will be saved. Calvin in his commentary on John 12:32 sees this problem and so downplayed the monergistic sense of the word and placed stronger emphasis on how Christ’s death on the Cross would result in a salvation that would include the non-Jews. Thus, Calvin does not take “all” literally but in the restricted sense of the elect, i.e., “the children of God, who belong to his flock.”

It might have been thought, that at that time he was carried away from the earth, so as no longer to have any interests in common with men; but he declares, that he will go in a very different manner, so as to draw upwards to himself those who were fixed on the earth. Now, though he alludes to the form of his death, yet he means generally, that his death will not be a division to separate him from men, but that it will be an additional means of drawing earth upwards towards heaven.

I will draw all men to myself. The word all, which he employs, must be understood to refer to the children of God, who belong to his flock. Yet I agree with Chrysostom, who says that Christ used the universal term, all, because the Church was to be gathered equally from among Gentiles and Jews. . . . (source; emphasis added.)

Evangelical scholar, Leon Morris, in his NICNT commentary on John, while understanding “draw” in the sense of a work of God and not a natural human response, recognizes that it would be problematic to read the passage as implying universal salvation (p. 598). To avoid universalism, Morris chooses to understand the verse as teaching the end of the particularism of Judaism and salvation being extended to non-Jews. While this reading softens the universalistic implications of John 12:32, it ignores the troubling implications of a literal compulsory understanding of ελκω in his commentary on John 6:44 (cf. Note 110 p. 371) and whether whether the figurative meaning of ελκω could have been used both John 6:44 and 12:32.

The early Church Father, John Chrysostom, in Homily LXVII, expounds on John 12:32 in which the same word ελκω appears.

“I will draw all men to Myself.” How then said He that the Father draweth? Because when the Son draweth, the Father draweth also. He saith, “I will draw them,” as though they were detained by a tyrant, and unable of themselves alone to approach Him, and to escape the hands of him who keepeth hold of them. In another place He calleth this “spoiling; no man can spoil a strong man’s goods, except he first bind the strong man, and then spoil his goods.” This He said to prove His strength, and what there He calleth “spoiling,” He hath here called “drawing.” (NPNF Vol. 14 p. 250; emphasis added)

In his subsequent sermon, John Chrysostom has no problem juxtaposing John 6:44 right next to John 12:32, neither does he append any qualifying remarks as a Calvinist might feel the need to do.

But by saying before, “No man can come to Me except the Father draw him”; and again, “If I be lifted up from the earth, I shall draw all men unto Me”; and again, “No man cometh to the Father but by Me”; He showeth Himself equal to Him who begat Him. (NPNF Vol. 14 p. 269; emphasis added)

What is worth noting here is how John Chrysostom’s syngergistic understanding of ελκω allows him to apply the same meaning to both John 6:44 and to John 12:32. This contrasts with the Reformed tradition’s attempt to apply the hard literal meaning of ελκω to John 6:44 to uphold the doctrine of predestination then seeking to apply the soft figurative meaning of ελκω to John 12:32 in order to avoid the implication of universalism. This inconsistent approach to ελκω in two similar settings within the same book raises questions about the linguistic validity of Reformed hermeneutics with respect to John 6:44.

The Monergistic Premise

The Reformed tradition’s doctrine of monergism—God as the sole cause of our salvation—predisposes its adherents to favor the more impersonal, coercive understanding of ελκω in John 6:44 and to ignore the figurative meaning of ελκω as persuasion. Ligonier Ministries hews to the uncompromising monergistic understanding of salvation:

The doctrine of the internal call cannot be avoided if we take the Bible seriously, and it leaves no room for man to play a part in his own salvation. Why do some people respond to the Gospel? Because God called them. Why do others not respond? Because God did not call them. (Source)

This stance is consistent with Calvin’s opposition to the notion of human cooperation with divine grace. He writes:

But here we must beware of two errors: for some make man God’s co-worker, to ratify election by his consent. (Institutes 3.24.3; p. 967)

This is not just Calvin’s opinion but reflects the formal position of the Reformed tradition. We read in the Westminster Confession Chapter 9 “Of Free Will”:

3. Man, by his fall into a state of sin, hath wholly lost all ability of will to any spiritual good accompanying salvation: so as, a natural man, being altogether averse from that good, and dead in sin, is not able, by his own strength, to convert himself, or to prepare himself thereunto. (Source; emphasis added.)

The belief in man’s total inability is closely related to the Protestant doctrine of sola gratia that it is only by divine grace that man is saved. This doctrinal framework predisposes Reformed Protestants to favor readings of John 6:44 as irresistible compulsion or as “voluntary” acceptance that originates in divine intervention.

Many Calvinists hold to the doctrine of man’s total inability because of Ephesians 2:1 “you were dead through the trespasses and sins” (RSV; emphasis added). They were taught that “dead” means the absence of any volitional capacity in man to respond to God’s grace unless God bestows upon him the ability to believe. However, if one reads the Parable of the Prodigal Son in Luke 15, one finds that the prodigal son who was “dead” (verse 32) also “came to himself” (verse 17) before returning home. There is no hint in Jesus’ parable of the wayward son being dragged home. The prodigal son returned home willingly and was welcomed by his loving father. Thus, the biblical basis for the Reformed TULIP is not as strong as some assume it to be.

In the Orthodox synergistic understanding of John 6:44, the focus is not on compulsion, but on who takes the initiative. With divine grace, it is God who takes the initiative and fallen humans who respond to the divine imitative either with acceptance or rejection. The Confession of Dositheus, which represents the Orthodox Church’s formal response to Reformed theology, affirmed man’s free will, even after the Fall. We read in Decree 14:

We believe man in falling by the [original] transgression to have become comparable and similar to the beasts; that is, to have been utterly undone, and to have fallen from his perfection and impassibility, yet not to have lost the nature and power which he had received from the supremely good God. For otherwise he would not be rational, and consequently not a human. So [he still has] the same nature in which he was created, and the same power of his nature, that is free-will, living and operating, so that he is by nature able to choose and do what is good, and to avoid and hate what is evil. For it is absurd to say that the nature which was created good by Him who is supremely good lacks the power of doing good. For this would be to make that nature evil — what could be more impious than that? (Emphasis added.)

The common ground shared by Orthodoxy and the Reformed tradition is the belief in prevenient grace, that it is God who takes the initiative in our salvation. Where the two traditions differ is with respect to man’s capacity to respond to divine grace. The Reformed understanding is that the Fall of Adam and Eve was of such catastrophic proportions that humans lost all ability—even volitional—to respond to God’s grace and so God needed to send the Holy Spirit to make us willing to believe in Christ. The Orthodox understanding is that even after the Fall man possessed free will and so had the freedom to accept or reject God’s grace. The synergistic understanding of salvation is not that of an interaction between equals; God has the upper hand, but he gives us the freedom to choose.

John 6:44 in Context

One problem with the Reformed reading of John 6:44 is that it fails to take into account how this verse fits into the overall context of John 6 – Jesus’ discourse on the Bread of Life. The backdrop to the Jews resisting Jesus’ claim to be the Bread of Life is Exodus 16 which describes how in response to the Israelites’ murmuring, Yahweh sent manna from heaven. As the Messiah who fulfills the Old Testament, Jesus is the new Moses who feeds the “elect” people with the true Bread from heaven. The prophetic type of the bread of heaven is fulfilled in the Son of God who came down from heaven in the Incarnation. The eating of manna in the desert finds fulfillment in having faith in Jesus as the Messiah and in entering into Eucharistic fellowship with Him. Thus, the unbelieving Jews of the Old Covenant are superseded by the new Israel represented by the Apostle Peter and the faithful disciples who remained even after so many stopped following Jesus (John 6:66-69). The Reformed interpretation of John 6:44 as teaching predestination holds up only if one isolates this verse to the exclusion of the overall context of John 6.

Leighton Flowers points out that the context for John 6:44 is the tension between the old Israel whose hearts were calloused and hardened and the new Israel—Jesus’ disciples. He notes that there is no suggestion in John 6 of God universally condemning all men to a totally disabled condition from birth due to Adam’s transgression and that salvation consists of God irresistibly drawing a preselected few. The Reformed reading of John 6:44 holds up only if one isolates this verse to the exclusion of the overall context. Flowers makes the intriguing suggestion that in the Bread of Life discourse Jesus was being deliberatively provocative, antagonizing the Jews, “judicially blinding Israel” in order to condemn the old Israel and to call out the faithful remnant of preselected Israelites who would make up the new Israel in the form of the Twelve.

What is the context for John 6:44? Verses 41-43 which immediately precede verse 44 contain the admonition that the Israelites ought to cease their murmuring against Jesus. The danger here is the Jews hardening their hearts against Jesus as the Israelites did against Yahweh in Moses’ time. So likewise it is important to note how John 6:44 is complemented by verse following it. Both verses 44 and 45 have the phrase “come to me.” Verse 44 points to God’s gracious initiative in drawing people to the Son; verse 45 teaches that we are drawn to the Son, not by compulsion, but through teaching. In the Incarnation God comes in the flesh and directly teaches men as was prophesied in Isaiah 54:13:

I will cause all your children to be taught by God, and your children to be in great peace. (NKJV, OSB)

Chapter 6 ends with large numbers of Jesus’ followers stumbling over the hard saying (v. 61) and parting ways with Jesus (v. 66). Here, John the Evangelist, like the Apostle Paul in Romans 9 to 11, is addressing one of the vexing theological problems facing the early Christian community: Why did the Jews—the elect people—reject the Messiah?

Thus, it is important when using passages like John 6:44 to formulate doctrine that we take into account the context of the passage. Furthermore, we should avoid rushing to link passages that use the literal, mechanical meaning to those that teach salvation in Christ. Yet this is what Ligonier Ministries has done. They cited John 18:10 a passage that describe a mechanical action—Peter’s drawing his sword—in order to interpret John 6:44 which is about man’s response to divine grace. The more sound approach is to cite biblical passages that pertain to our salvation in Christ (e.g., John 12:32) and omit passages that pertain to mechanical actions. If they had been willing to allow for ελκω with the sense of persuasion as in Jeremiah 31:3 and Song of Songs 1:4 in the Septuagint, the folks at Ligonier Ministries could have avoided many theological and exegetical difficulties. It is regrettable that Ligonier Ministries has succumbed to clumsy proof texting instead of using a simpler and more direct lexical solution – the figurative sense of ελκωas as persuasion or wooing.

The Range of Meaning of ελκω – “to draw”

There are multiple meanings for the Greek word ελκω “to draw.” This means that interpreting John 6:44 is not a simple matter as many in the Reformed tradition would assume. Louw and Nida’s Greek-English Lexicon’s entry for ‘ελκω‘ lists two meanings: (1) to pull often implying resistance (Vol. 1 15.212; p. 205) and (b) to lead by force (Vol. 1 15.178; p. 208). It is quite surprising that this fine lexicon did not touch on the figurative meaning for ελκω. Also, the lexicon makes no mention of John 6:44 and 12:32, two passages that use ελκω in relation to our salvation in Christ. Arndt and Gingrich’s lexicon lists two categories of meaning for ελκω: a literal physical meaning and a figurative meaning: “of the pull on man’s inner life.” They assigned to ελκω in John 6:44 and 12:32 the figurative meaning: to draw or to attract. Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament likewise assigns the figurative meaning of ελκω to the two verses. It notes that in the Septuagint, ελκω had the sense of “drawing to oneself in love.”

The Greek word ελκω is normally used in the sense of drawing or pulling on an inanimate object, or of pulling a person through physical force: the Apostle Peter drawing out his sword (John 18:10) or the disciples pulling on their nets in the post-resurrection account in John 21:6 and 11. Determining the appropriate meaning becomes more complicated when ελκω is is applied to humans. It can be applied externally to the physical body or internally implying persuasion. In the book Acts, we find ελκω used in the sense of physical force applied to unwilling subjects, e.g., the Apostle Paul and his companion Silas dragged into the marketplace (Acts 16:19), and the Apostle Paul on another occasion being dragged out of the Jerusalem temple (Acts 21:30). James in his epistle makes reference to the common practice of the rich dragging the poor to court (2:6).

In the Septuagint (the Greek Old Testament), we find a range of meanings for ελκω, from physical force to persuasion. In Jeremiah 45:13 is a positive example of physical force being applied to a human being: Jeremiah being pulled out of the pit by means of ropes cushioned with old rags. David’s song in 2 Kingdoms 22:17 (2 Samuel 22:17) refers to Yahweh drawing him out of many waters, evoking the image of a lifeguard pulling a drowning man out the deep waters.

The Septuagint also uses ελκω in the sense of persuasion. In Jeremiah 38:3, we read:

I have loved you with an everlasting love; therefore, I drew you in compassion, O virgin of Israel. (OSB; emphasis added; cf. Jeremiah 31:3 MT)

κύριος πόρρωθεν ὤφθη αὐτῷ ἀγάπησιν αἰωνίαν ἠγάπησά σε διὰ τοῦτο εἵλκυσά σε εἰς οἰκτίρημα (source; emphasis added.)

In the Song of Songs 1:4, we find ελκω used in the sense of persuasion.

They draw you. We will run after you, For the smell of your ointments. The king brought me into his chamber. (OSB; emphasis added.)

εἵλκυσάν σε ὀπίσω σου εἰς ὀσμὴν μύρων σου δραμοῦμεν εἰσήνεγκέν με ὁ βασιλεὺς εἰς τὸ ταμίειον αὐτοῦ (source; emphasis added.)

These verses tell us that the Greek ελκω can be understood in the sense of physical force or as persuasion. Absent in the Septuagint are passages that suggest the Reformed understanding of internal compulsion against one’s free will.

To sum up, there are at least three meanings for ελκω:

• Inanimate Objects – physical force: Peter drawing his sword from its sheath (John 18:10); Peter and his companions pulling the nets (John 21:6).

• People – physical force: Paul dragged bodily from the marketplace (Acts 16:19) or from the Temple (21:30); Jeremiah pulled out of the pit (Jeremiah 45:13; cf. 2 Samuel 22:17); the rich dragging the poor into the courtroom (James 2:6).

• People – persuasion or wooing: Yahweh drawing Israel by His love (Jeremiah 38:3 in LXX; cf. Jeremiah 31:3 MT); the beloved calling out to her love in Song of Songs 1:4)

Given this range of meanings, our task is ascertaining the appropriate category of meaning for ελκω for John 6:44 and 12:32. One important clue is that in John 6:44 and 12:32 ελκω is used in the context of personal relationships: Christ and the individual believer in John 6:44 and Christ saving the world in John 12:32. To treat salvation in Christ as an impersonal compulsion would be a dubious undertaking. One could argue for the mechanical understanding of ελκω by appealing to man’s total inability, however that would be to import wholesale the theological system known as TULIP into John 6 which makes no mention whatsoever of total depravity or predestination. The Reformed interpretation of John 6:44 is more eisegesis (reading doctrine into the text) than exegesis (drawing doctrine from the text). Furthermore, the Reformed exegetes’ inconsistent application of one sense of ελκω for John 6:44 and a different one for John 12:32 sacrifices the linguistic integrity of biblical hermeneutics for the sake of upholding a novel theological system.

Conclusion

The Reformed tradition’s attempt to use a literal, compulsory meaning of ελκω for interpreting John 6:44 is problematic for several reasons. First, in order to read verse 44 as supporting predestination one would need to isolate verse 44 from the broader context of John 6. There is no hint or suggestion of the Fall, man’s total depravity, irresistible grace, or predestination in Jesus’ exposition on the bread of life – the main theme of chapter 6. The Calvinist reading of John 6:44 depend on reading certain assumptions into the text. This projecting of the Reformed theology onto the biblical text is questionable and deserves to be criticized.

Second, using the literal, coercive understanding of ελκω in John 6:44 leads to significant theological difficulties if it is applied likewise to John 12:32. The problem of universalism can be avoided if we understand ελκω in the more figurative sense of wooing. This is a much simpler and direct solution than the Reformed exegetes’ clumsy solution of applying the literal meaning of ελκω to John 6:44 and the allegorical meaning to John 12:32. This semantic inconsistency doesn’t make sense.

Third, using the figurative, relational definition for ελκω is consistent with the early Church Father’s affirmation of human free will. To sum up, the Reformed interpretation of John 6:44 involves: proof texting, eisegesis over exegesis, potential universalism, questionable handling of the Greek language, the ignoring the immediate context of John 6, and the ignoring of historical theology.

While the Reformed reading of John 6:44 founders on linguistic, contextual, and historical grounds, John Chrysostom’s reading of John 6:44 does a much better job in reflecting the meaning of ελκω, the context of John chapter 6, and the historic Christian Faith. To the reader who submitted the original query, I hope this article answers your concerns about John 6:44 and is of help to you in your journey to Orthodoxy.

Looking Ahead

I hope in the future to address other aspects of the Reformed tradition’s soteriology. The Calvinist paradigm, which has so profoundly influenced many people’s understanding of salvation and God’s character, is based on assumptions that need to be critically examined in the light of Scripture and the teachings of the early Church Fathers. Among the assumptions that deserve scrutiny are the human condition after the Fall, man’s freedom to love God or to suppress the Truth of God, and the problem of theodicy — God’s absolute sovereignty becoming the cause of sin. The early Church Fathers in their wisdom recognized that even though fallen and deeply flawed, man still retained the divine image and so possessed the freedom to respond to God’s loving initiative in Christ or to suppress the truth also by his own free choice. I also hope to compare Semi-Pelagianism and Arminianism—two theological systems that the Reformed tradition has so strongly opposed—against the teachings of early Church Fathers. I suspect that many of the problematic aspects of Calvinist soteriology can be traced to the West’s departure from the ancient patristic consensus. The Calvinist paradigm is a complex system of interrelated ideas which means it cannot be refuted with one single argument. Persuading sincere inquirers to relinquish their Calvinism will require a wide-ranging critique. Also needed is persuading the inquirer to embrace the ancient Church’s soteriology which is articulated in the ancient liturgies that recalled and celebrated Christ’s work of salvation through his Incarnation, his life on earth, his saving death on the Cross, and his third-day Resurrection by which he destroyed Death and Hell in order to restore us to life with God.

Robert Arakaki

References

Arndt and Gingrich. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature.

Nathaniel W. Bingham. “Charles Spurgeon on Calvinism – Irresistible Grace.” Ligonier Ministries

Raymond E. Brown. Anchor Bible Commentary on John I-XII.

John Calvin. Commentary on John. BibleHub.com

John Calvin. Institutes Vol 1 and 2. Ford Lewis Battles, editor and translator.

Leighton Flowers. “John 6 – “Down From Heaven”: Why Context Kills Calvinism.”

German Bible Society. Septuagint. Academic-bible.com

Gerhard Kittel. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Vol. II p. 503

Ligonier Ministries. “Effectual Calling.”

Ligonier Ministries. “Man’s Radical Fallenness.”

Johannes P. Louw and Eugene A. Nida. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains. VOL I & II.

Leon Morris. NICNT Commentary on John.

Erwin Nestle and Kurt Aland. Novum Testamentum Graece | 28. German Bible Society.

Alfred Rahlfs. Septuaginta. Vol. II.

C.H. Spurgeon. “How Men Come to Christ.” Monergism.com

Note: In an earlier version of “Man’s Radical Fallenness,” Ligonier Ministries apparently mistyped John 6:44 as John 6:65. In light of their recent correction, I am retracting my earlier criticism of their reading of the Greek text. Thanks to Jon H for bringing this to my attention! [11 October 2018]

Recent Comments