John Calvin source

On 23 May 1555, John Calvin preached on Deuteronomy 4:15-20 applying Moses’ admonition against idols to the depicting of Jesus Christ in icons. This sermon is significant for Reformed-Orthodox dialogue because it presents us not only with Calvin’s hermeneutical method but also the theological reasoning underlying his iconoclasm.

In my article, “The Biblical Basis for Icons,” I pointed to the use of images of cherubim on the curtains of Moses’ Tabernacle and images of cherubim carved on the walls of Solomon’s Temple. Then in another article, “Calvin Versus the Icon,” I wondered about Calvin’s failure in his Institutes or his commentaries to address these pro-icon passages. This made me curious about how Calvin would have responded to these passages in the Bible that support images in the church. It turned out that Calvin in his 1555 sermon did address this issue. We are fortunate to have Arthur Golding’s English translation of Calvin’s sermon series on Deuteronomy posted online by the University of Michigan. The reader should keep in mind that Golding (1536-1606) lived in the sixteenth century which accounts for what seems to us peculiar English spelling.

And whereas the alledge that there were Cherubins painted vppon the vaile of the Temple,* and that two likewise did couer the Arke: it serueth to con∣demne them the more. When the Papistes pre∣tend that men may make any manner of image: What, say they? Hath not God permitted it? No: but the imagerie that was set there, serued to put the Iewes in minde that they ought to abstaine [30] from all counterfeiting of God, insomuch that it was a meane to confirme them the better, that it was not lawfull for them to represent Gods Maiestie, or to make any resemblance thereof. For there was a vaile that serued to couer the great Sanctuarie, and againe there were two Cherubins that couered the Arke of ye couenant. Whereto commeth all this, and what is ment by it, but that when the case concerneth our going vnto God, we must shut our eyes and not preace [40] any neerer him, than he guideth vs by his word? Then let vs hearken to that which he teacheth, and therewithall let vs bee sober, so as our wits bee not ticklish, nor our eyes open to imagine or conceiue any shape. (Emphases added.)

Calvin’s reasoning here is a curious one. He argues the cherubim were depicted in the Temple: (1) to condemn the Israelites and (2) to remind them to abstain from making idols. It is as logical as a teetotaler parent’s taking a drink in order to teach his children to abstain from alcohol, or a college professor copying another professor’s work in order to teach his students the wrongfulness of plagiarism. In my earlier assessment of Calvin I took an irenic stance by titling the sub-section “The Logic of Calvin’s Iconoclasm.” However, Calvin’s peculiar exegesis in this sermon leads me to a quite different conclusion: “The Illogic of Calvin’s Iconoclasm.”

When reading the Old Testament it is important for Christians to interpret the text in light of the coming of Christ. In his sermon, Calvin applies Deuteronomy against the Roman Catholics as if they were living in the Old Testament dispensation. Calvin here seems to have skipped over the Incarnation. This is a huge omission because the early Church Fathers saw the Incarnation as a “game changer.” Prior to the coming of Christ humanity was estranged from God and pagans sought to worship God in the light of their understanding of him. This led to all sorts of pagan rituals and idols, and erroneous beliefs about his character. God’s meeting with Moses on Mt. Sinai marked the beginning of the restoration of the true knowledge of God which would culminate in the coming of Christ. John of Damascus explained how the Incarnation was a game changer.

It is clearly a prohibition against representing the invisible God. But when you see Him who has no body become man for you, then you will make representations of His human aspect. When the Invisible, having clothed Himself in the flesh, become visible, then represent the likeness of Him who has appeared. When He who, having been the consubstantial Image of the Father, emptied Himself by taking the form of a servant, thus becoming bound in quantity and quality, having taken on the carnal image, then paint and make visible to everyone Him who desired to become visible (in Ouspensky 1978:44).

As a result of the Incarnation the life of Christ takes on a revelatory character. We come to know God’s character not just through the teachings and sayings of Christ but also through his actions. The Orthodox Church sees the Trinity being revealed in Christ’s baptism in the Jordan and his transfiguration on Mt. Tabor.

John’s First Epistle likewise makes the case that in the Incarnation God the Son became visible and tangible.

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched…. (1 John 1:1; emphases added)

Calvin’s polemic against images makes sense if God was up in heaven far beyond human knowing and comprehension. In the Old Testament times it was impossible for man to ascend up to the heavens by his own power to behold God. Knowledge of God was only possible if God condescended to come down from heaven and showed himself to the patriarchs: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, or on Mt. Sinai as he did with Moses or through the prophets like Isaiah or Jeremiah. God’s condescension culminated in his taking on human flesh and dying on the Cross (Philippians 2:5-11).

Are Icons Nestorian?

Calvin makes another argument against depicting Christ in images. He argues that to depict Christ in images is a form of the Nestorian heresy.

Beholde, they paint and portray Iesus Christ, who (as wee knowe) is not onely man,* but also God manifested in the flesh: and what a representation is that? Hee is Gods eternall sonne, in whom dwelleth the fulnesse of the Godhead, yea euen substantially. Seeing it is said, substantially, should wee haue portraitures and images whereby the onely flesh may bee re∣presented? Is it not a wyping away of that which is chiefest in our Lorde Iesus Christ, that is to wit, of his diuine Maiestie? (Emphases added.)

In this passage Calvin makes two arguments. First, he affirms the two natures of Christ: human and divine. Second, he argues that because only the human nature can be depicted in a painting the result is a Nestorian heresy in which Christ’s humanity is separated from his divinity.

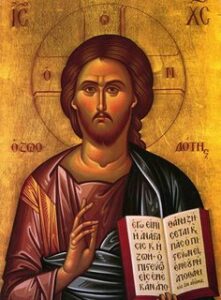

Orthodoxy has two responses to this. One, the icon depicts the Person of Christ. This can be seen in the prominence of the face in icons. Therefore, when Orthodox Christians venerate an icon of Christ their devotion is directed to the Person of Christ, not to his physical nature or the colored paint on the wooden board. The Person of Christ encompasses both his divine and his human natures. Two, Orthodox icons of Christ have symbolic references to Christ’s divinity. Typically, in the Pantocrator icon we see Christ’s red tunic overlaid with the blue mantle. The underlying red symbolizes Christ’s essential divine nature whereas the blue symbolizes his taking on human nature as an act of grace.

The visual depiction of Christ’s humanity is accompanied by symbolic references to his divine nature. We see inscribed on the Pantocrator icon the Greek phrase “Ο ΩΝ” which means “He Who Is.” This is taken from the book of Revelation:

Holy, holy, holy

Is the Lord God Almighty,

Who was, and is, and is to come.

(Revelation 4:8)

For the Orthodox Calvin’s theological critique of icons is fundamentally flawed. His ignorance of the principle that icons depict the person leads him to a Nestorian understanding of icons. In other words it is Calvin who is committing the heresy of Nestorianism, not the pro-icon Orthodox! We don’t know what kind of images Calvin saw in the Roman Catholic churches of his time but in Orthodox iconography there are safeguards in place to guard against Nestorian heresy that viewed his humanity as separate from his divinity.

Conclusion

For an Orthodox Christian, Calvin’s sermon against images is seriously flawed. One, Calvin’s neglecting to interpret Deuteronomy in the light of the Gospels, i.e., the Incarnation of the Word, results in anachronistic hermeneutics. He criticizes the use of images in Roman Catholic churches as if they were living in Old Testament times. Two, Calvin’s reading of Old Testament passages where God instructed Moses to have images of the cherubim woven into the Tabernacle curtains as being iconoclastic in intent make no sense whatsoever. Three, Calvin’s accusation of the implicit Nestorian nature of icons shows a fundamental misunderstanding of icons in Orthodoxy. Calvin’s accusation of Nestorianism holds up if evidence can be shown that the Church Fathers or Ecumenical Councils understood icons as depicting only Christ’s human nature. Four, Calvin’s failure to see icons depicting the Person of Christ leads him to an inadvertent Nestorian heresy.

If a Reformed Christian visiting an Orthodox Liturgy were to observe an Orthodox Christian venerating an icon of Christ they should refrain from jumping to the conclusion that the Orthodox parishioner is worshiping the painting of Christ or his physical nature. When an Orthodox Christian venerates an icon he or she is showing love and respect to the Person who came down from heaven and died on the Cross for their sins.

It may be that Calvin’s iconoclasm was the result of his being embroiled in the heated Protestant versus Roman Catholic polemic of the time. Reformed Christians today are fortunate to have the opportunity to engage in dialogue with Orthodox Christians who are familiar with both the Reformed and the Orthodox theological traditions. [I am grateful for the grounding in Reformed theology that I received at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary prior to my becoming Orthodox.] Icons have been a longstanding stumbling block between the two traditions. If it can be shown that Calvin’s iconoclasm is based on a flawed understanding of icons and that the Orthodox pro-icon position is grounded in Scripture then the possibility emerges for a rapprochement between the two traditions.

Robert Arakaki

See also:

“Are Images of Jesus Idolatrous?” by Jason Goroncy in Per Crucem ad Lucem.

“What is Calvin’s Take on Images of Jesus?” by Eric Parker in The Calvinist International.

“Are icons Nestorian?” in Wicket’s Take.

Theology of the Icon by Leonid Ouspensky, Volume I (1978).

!["And was-given to-him [the] book of-Isaiah [the] prophet" Source](https://orthodoxbridge.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/12285835_10207045744095581_1925439008_n.jpg)

Recent Comments