A Response to Pastor Toby Sumpter

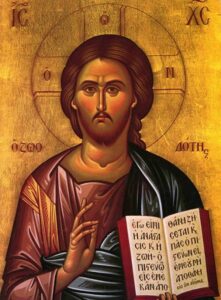

Rev. Toby Sumpter’s “A Plea & A Sketch of an Argument on Icons” is not a simplistic bashing of icons. Rather, he has taken the trouble to engage the Christological issues underlying the iconoclastic debates. Among the earlier objections to icons was the two-fold argument that either icons depict Christ’s divinity, and by doing so circumscribed the divine Being, falling into the heresy of monophysitism, or they depict only Christ’s humanity and by doing so separated his humanity from his divinity, falling into the heresy of Nestorianism. The Orthodox answer, reflecting Chalcedonian Christology, is that icons depict the Person of Christ, who is both divine and human. Toby Sumpter takes Orthodoxy’s Chalcedonian premise that icons depict the Person of Christ as the starting point for his argument. He reasons that if icons are inaccurate or lack sufficient details, then Orthodox Christians, despite their sincerity, are venerating something other than Christ. He writes:

Thus, to be in accordance with Nicaea II and Theodore, the Orthodox position really must insist that the icons of Christ are in fact true representations of the man Jesus Christ and that whenever they have seen His icon, they have truly seen Christ.

. . . .

And here we arrive at long last at the problem. First, let us grant that if there had been photographers on site in Judea during the earthly days of Jesus it would have been fine to take pictures of Jesus, preserve those pictures, and venerate those pictures. For the sake of argument, let’s grant that the Seventh Ecumenical Council’s argument is sound in principle. The question comes down to whether we have strong enough evidence to believe that the icons we now have are in fact accurate portraits of Christ. And very much related to that, did Jesus and the apostles intend for a central part of the ministry of the Church to be through the making and venerating of images? The actual historical evidence seems decidedly against this.

. . . .

In other words, there are hefty biblical and historical arguments against assuming that modern icons of Christ actually resemble the Jewish man they claim to. And if they do not, they are not in fact the hypostasis of Christ, and therefore we are left with millions of Christians praying in front of pictures of someone else. Either that someone else is real and exists (but we don’t know them[sic]) or else the canonized face of Jesus is the result of the composite imagination of artists. (Emphases added)

In short, he attempts to show how the Orthodox position on icons, even with its Chalcedonian premise, is untenable and therefore leads to iconoclastic conclusions.

Misleading Question

Pastor Sumpter’s focus on accurate physical depictions of Christ is, from the Orthodox standpoint, entirely off-base. By framing his question in terms of the need for accurate depictions of Christ’s physical features in icons, Sumpter assumes that the purpose of Orthodox icons is to depict the physical features of the human Christ, not his Person. Here he confuses Christ’s physical nature with his Person in the icon. In doing so, he inadvertently frames his question in a way that departs from the Chalcedonian focus on the Person uniting the two natures; thus, he reverts to the heretical alternatives that assumed icons relate to the natures of Christ. The Orthodox understanding is that icons relate us to the Person of Christ. However, Sumpter’s question by focusing on Christ’s physical features assumes that icons relate us to the human nature of Christ. In other words, Pastor Sumpter’s question is not rooted in Chalcedonian Christology but rather reverts to the heretical alternatives that confused the natures for the Person. Furthermore, implicit in Toby Sumpter’s iconoclasm is a decidedly heretical non-Chalcedonian Christology!

Pastor Sumpter’s argument was anticipated by Leonid Ouspensky, who wrote in Theology of the Icon:

Thus, iconoclastic thought could accept an image only when this image was identical to that which it represented. Without identity, no image was possible. Therefore an image made by a painter could not be an icon of Christ. (p. 124; emphasis added)

But the Orthodox, fully aware of the distinction between nature and person, maintain precisely this third possibility, which abolishes the iconoclastic dilemma. The icon does not represent the nature, but the person: Περιγραπτος αρα ο Χριστος καθ υποστασιν καν τη θεοτητι απεριγραπτος, “Christ is describable according to His hypostasis, remaining indescribable in His Divinity,” explains St Theodore the Studite. When we represent our Lord, we do not represent His divinity or His humanity, but His Person, which inconceivably unites in itself these two natures without confusion and without division, as the Chalcedonian dogma defines it. (p. 125; emphases added)

This articulation of icons’ otherworldly vantage point is shared by Paul Evdokimov in The Art of the Icon. He writes:

Now the iconic likeness is radically opposed to natural likeness, to natural portraiture, and only relates to the hypostasis, that is, the person, and to his heavenly body. (p. 87)

Pastor Sumpter’s argument that the absence of exact correspondence between icon and the prototype invalidates icons is not new. Theodore the Studite anticipated this in his apologia On the Holy Icons:

1. An objection as from the iconoclasts: “If everything which is made in the likeness of something else inevitably falls short of equality with its prototype, then obviously Christ is not the same as His portrait in regard to veneration. And if these differ, the veneration which you introduce differs also. Therefore it produces an idolatrous worship.”

Answer: The prototype is not essentially in the image. If it were, the image would be called prototype, as conversely the prototype would be called image. This is not admissible, because the nature of each has its own definition. Rather, the prototype is in the image by the similarity of hypostasis, which does not have a different principle of definition for the prototype and for the image. (pp. 102-103; bold type added)

Theodore argues that the link between the icon and the prototype (Christ) is not found in essence (ousia) but rather in the person (hypostasis) being depicted. In other words, iconoclasts erred when they located the connection in the essence (ousia) rather than the person (hypostasis). In doing so, early iconoclasts deviated from the Chalcedonian principle of the enhypostatic union as the basis for Orthodox Christology and iconography.

Note: “enhypostatic” means “in-person.” It refers to the union of the two natures of Christ in his Person. The Evangelical Theological Dictionary’s entry for “Hypostatic Union” has this definition: “In the incarnation of the Son of God, a human nature was inseparably united forever with the divine nature in the one person of Jesus Christ, yet with the two natures remaining distinct, whole, and unchanged, without mixture or confusion so that the one person, Jesus Christ, is truly God and truly man.” (1984, Elwell ed.) This understanding comes from the Council of Chalcedon (451).

In the icon, we encounter the Person of Christ. Key to understanding the Orthodox veneration of icons is prayer. There can be no veneration apart from prayer. This is due to the fact that the veneration of icon is an act of prayer. And key to prayer is calling on the divine Name of Christ. This is because to invoke the divine Name is to call on the Person who bears that Name. There is, within the Jewish tradition, a deep reverence for the divine Name. I learned this when I bought a yarmulke for a friend of mine years ago. I asked the lady at the counter what made it a holy object and she explained that God’s name was woven into it. Similarly, because the icon of Christ not only depicts the Word made human flesh, but also bears the name “Jesus” given to him at his birth, it becomes a holy object. Ouspensky writes:

The icon is joined to its prototype because it portrays the person and carries his name. This is what makes communion with the represented person possible, what makes him known. (Ouspensky p. 127; emphasis added)

And,

In an icon, the Hypostasis, Christ’s person, “enhypostasizes” not a substance (the wood and colors) but the likeness. It is the likeness alone and not the board that is the meeting place where we encounter the presence. This likeness is fundamental to an understanding of the real nature of the icon. (p. 195; italics in original)

In other words, Toby Sumpter’s insistence on the need for an exact visual (photographic) representation of Christ diverts him from the Chalcedonian emphasis on the Person of Christ to the heretics’ misguided emphasis on the human nature of Christ. Rather than refute Nicea II, he merely rephrases the earlier iconoclastic arguments in the form of a question.

Given Pastor Sumpter’s earlier exhortation that we do our homework, it comes as a surprise that he apparently has not read Ouspensky’s Theology of the Icon, which anticipates his objection. Nor, it seems, did he read Theodore the Studite carefully. And, even more telling is the fact that he failed to grasp the categories used in Chalcedonian Christology. His confusing nature with person led to his misleading question and his erroneous iconoclastic conclusion! A muddled Christology is a bad starting point for doing theology.

Depicting Christ

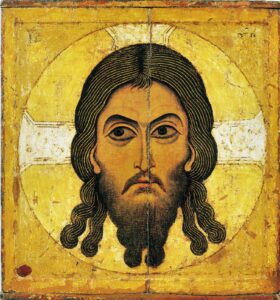

One important question is whether there is evidence of visual depictions of Christ that can be traced back to the time of Christ. The Orthodox understanding that icons form part of Holy Tradition implies that icons have been present in Christianity from the start. Ouspensky wrote: “Thus, the Church maintains that authentic images of Christ have existed form the very beginning.” (p. 58)

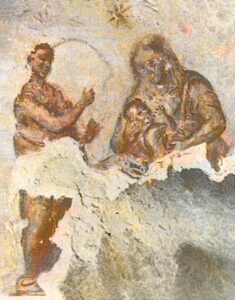

One important early witness to icon making is Eusebius’ Church History. In the fascinating passage about a statue made in memory of Jesus’ healing the woman with the issue of blood is a passing reference to paintings being made of Christ and the Apostles.

Nor is it strange that those of the Gentiles who, of old, were benefited by our Saviour, should have done such things, since we have learned also that the likenesses of his apostles Paul and Peter, and of Christ himself, are preserved in paintings, the ancients being accustomed, as it is likely, according to a habit of the Gentiles, to pay this kind of honor indiscriminately to those regarded by them as deliverers. (Book VII Chapter 18, NPNF Vol. I p. 304; emphases added)

Eusebius’ statement about the “likeness” of Christ and his Apostles being “preserved in paintings” points to icons having been a longstanding practice in the early Church.

There is, in the Orthodox Tradition, the icon known as the Acheiropoietos (Made Without Hands). This particular icon is commemorated on August 16. The sticheron (hymn) for this particular feast day goes: “After making an image of Your most pure image, You sent it to the faithful Abgar, who desired to see You, who in Your divinity are invisible to the cherubim.” In other words, the Acheiropoietos icon is not incidental to Orthodoxy, but integral. The story behind this unusual icon is related in the Festal Menaion for the month of August:

King Abgar, a leper, had sent to Christ his archivist Hannan (Ananias) with a letter in which he asked Christ to come to Edessa to heal him. Hannan was a painter; and in case Christ refused to come, Abgar had advised Hannan to make a portrait of the Lord and bring it to him. Hannan found Christ surrounded by a large crowd; he climbed a rock from which he could see him better. He tried to make His portrait but did not succeed “because of the indescribable glory of His face which was changing through grace.” Seeing that Hannan wanted to make His portrait, Christ asked for some water, washed Himself, and wiped His face with a piece of linen on which His features remained fixed. He gave the linen to Hannan to carry it with a letter to the one who had sent him. In His letter, Christ refused to go to Edessa Himself, but promised Abgar to send him one of His disciples, once His mission had ended. (Note 2 in Ouspensky p. 51)

If taken at face value, this anecdote about the Acheiropoietos icon rebuts Pastor Sumpter’s claim that early icons of Christ are the result of human imagination and therefore without historical basis. But, while the Acheiropoietos icon has been accepted by Orthodoxy, its provenance is problematic to non-Orthodox scholars. The earliest historical references date back to the fifth century, e.g., the Doctrine of Addai and Evagrius Scholasticus in his Ecclesiastical History (Ouspensky p. 52). Christopher Jones in “The Letters of Abgar” ended on a cautious note: “We also have little corroborating evidence that they did happen. So, like many thorny problems in ancient history, we can only look on our meager sources and wonder.”

Another witness to the antiquity of icon-making is the tradition that Luke the Evangelist in addition to writing Luke and Acts also painted the first icon of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child. The Orthodox Church commemorates Luke’s painting the icon of Mary and her giving her approval of the painting on the feast day of Our Lady of Vladimir (Ouspensky pp. 62-3).

The Wikipedia article “Depiction of Jesus” notes the historical development of visual depictions of Christ.

The depiction of him in art took several centuries to reach a conventional standardized form for his physical appearance, which has subsequently remained largely stable since that time. Most images of Jesus have in common a number of traits which are now almost universally associated with Jesus, although variants are seen.

A review of Orthodox icons compared with other ancient icons from the Latin, Coptic, and Ethiopian traditions shows striking similarities despite stylistic differences. This underlying similarity points to a broad catholic visual tradition in the early Church. For an overview of the various icons depicting Christ, see Betsy Porter’s website and Columbia University’s “Faith, Imagined – Early Christianity.” This consensus among the historic churches serves as evidence against Pastor Sumpter’s assertion that icons of Christ to be the product of the imagination of artists. Moreover, the recognizability of the icons of Christ challenges Pastor Sumpter’s insistence on the need for exact visual correspondence with Jesus’ appearance “according to the flesh.”

Do We Need a Photo ID of Christ?

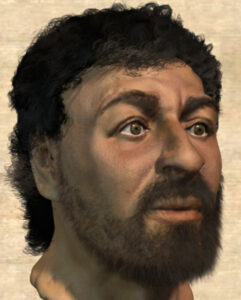

What did Jesus of Nazareth actually look like? The fact that the palace guards sent by the Jewish leaders had to rely on Judas to point out Jesus suggests that Jesus’ physical appearance was not markedly different from other Jewish men of his time (see Mark 14:43-46). Recently, a retired medical artist, Richard Neave, attempted to reconstruct Jesus’ appearance relying on the science of forensic medicine. However, this concern with capturing Jesus’ physical appearance is at odds with Orthodoxy’s priorities.

Orthodox iconography is based on the assumption of there being a new heaven and new earth under Christ’s rule. Ouspensky writes:

We therefore do not know what the first icons of Christ and of the Virgin were like. But the little that remains of primitive art leads us to surmise that the first images were not purely naturalistic portraits, but rather images of a completely new and specific Christian reality. (p. 65)

Christian iconography attempts to convey what is visible to the human eyes and also that which is invisible, i.e., the spiritual content of that which is being presented. This can be seen in ancient catacomb art, which combined direct images with abstract symbols.

Another characteristic trait of Christian art, which can be seen already in the first centuries, is that the image is reduced to a minimum of details and to a maximum of expression. Such laconism, such frugality in methods, corresponds to the laconic and subdued character of Scripture. . . . . Similarly, the sacred image portrays only the essential. Details are tolerated only when they have some significance. (Ouspensky p. 78)

Dangerous Implications

Pastor Sumpter’s argument that the absence of historical accuracy with respect to the historical Jesus invalidates Orthodox icons has dangerous implications. If his argument is valid, then one can likewise argue that if we do not have the exact words of Christ, but rather mediated and redacted versions, then the Gospel accounts are likewise invalid, and that we are reading the words of mere men. This quest for the true and genuine sayings of Jesus of history reflects an aspect of higher critical biblical scholarship. One of the unfortunate consequences of higher critical skepticism is a distrust of the veracity of Scripture and the belief that behind the “Christ of faith” is the supposedly true “Jesus of history.”

If exact visual correspondence is needed between icons and Jesus’ human face, then it could also be argued that valid prayer requires that we use Jesus’ name in the original Aramaic. This would also imply that our Anglicized version of the Greek “Iesous” is likewise incorrect and invalid, and that God does not hear our prayers, no matter how sincere they may be. This kind of logic lies behind Islam’s insistence that proper performance of the salat (five daily prayers) be done in Arabic, no matter the native language of the worshiper.

“Blessed are the Eyes that See What You See”

Pastor Toby Sumpter laid out a string of proof texts to bolster his position that faith in Christ requires no visual content. However, a review of Scripture shows that seeing is not antithetical to believing, and that the two complement each other. When John the Baptist’s faith was wavering, Jesus told John’s followers: “Go back and report to John what you have seen and heard.” (Luke 7:22) Jesus told his disciples that in comparison to the Old Testament saints who lived prior to the coming of Christ and had to go by the prophetic promises of the coming of Christ, they were blessed to be able to see Christ with their own eyes and hear the words of Christ with their own ears. (Luke 10:23-24) Paul, in defense of his apostolic ministry, asked the Christians in Corinth: “Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?” (1 Corinthians 9:1) The Risen Christ commanded the Apostle John: “Write, therefore, what you have seen . . . .” (Revelation 1:19) Jesus told Nathaniel: “You believe because I told you I saw you under the fig tree. You shall see greater things than that. . . . . I tell you the truth, you shall see heaven open, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man.” (John 1:50-52) And then, there is the verse we Orthodox love to quote to our non-Orthodox friends: “Come and see.” (John 1:46)

How Orthodox Relate to Icons

Can Orthodox Christians pray to God without icons? The answer is an unequivocal Yes! Icons are meant only to aid us in prayer. They make visible the invisible reality of heaven. They remind us of the spiritual dimension, and so strengthen our faith in Christ. It is not as if icons were essential for our making contact with God. Implicit in Toby Sumpter’s critique is the assumption that icons are much like telephones and that the wrong area code can result in a disastrously misdirected phone call.

Key to effective prayer is faith in Christ. But key to faith in Christ is right Christology. Having a heretical Christology derails one’s prayer and worship life. In Orthodoxy, especially in the Liturgy, the Christological and Trinitarian dogmas frame our prayers and our prayers express the dogmas of the Church. In order to pray genuinely one must be in a relationship with Christ, which is to have Christ as one’s God and Savior. Orthodox prayer is not like magic where one needs to perform special rites and utter magical formulas for something to happen. Christian prayer is grounded in God’s mercy to us sinners and in our response to him. Without faith, that is, without a personal commitment to Christ, the veneration of icons is an empty ritual; the presence of faith makes the veneration of icons a sacramental encounter with the Risen Christ. Paul Evdokimov writes:

In a nutshell, the icon is a sacrament for the Christian East; more precisely, it is the vehicle of a personal presence. (p. 178; italics in original)

Ouspensky writes:

The icon is not an image of the divine nature. It is an image of a divine person incarnate; it conveys the features of the Son of God who came in the flesh, who became visible and could therefore be represented with human means. (p. 127)

In another passage, Evdokimov described the icon as being “charged with a presence.” (p. 178) He notes that where the Christian West approach icons from the standpoint of anamnesis (memory), Orthodoxy stresses instead the epiphanic (revelatory) presence in icons. (p. 180)

Where the Reformed Christian may view religious pictures as having primarily a pedagogical function, i.e., as a stimulus to mental reflection, the Orthodox Christian sees icons as having a far more sacramental purpose, i.e., as a stimulus to prayer, a uniting of the spiritual with the physical, and beyond that, as a means to deepening one’s communion with Christ and the saints, who are far more present than we imagine.

The Christian painter renounces the naturalistic representation of space, so noticeable in the Roman art of this time. The Christian painter depicts neither depth nor shadow in his work. . . . . They are almost always represented face on, as we have already said. They address the viewer and communicate their inner state to him, a state of prayer. (Ouspensky pp. 78-79)

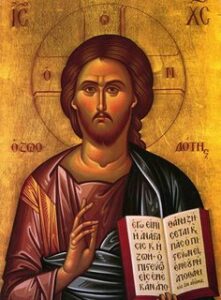

In the context of Orthodoxy, it is impossible for an icon of Christ to mislead one into false worship. The possibility of a misdirected veneration is prevented by the safeguards within Orthodoxy. First, regular attendance at the Liturgy will result in familiarity with the icons of Christ and the other saints. Icons are liturgical art. One learns about who Jesus is through the Gospel readings and through receiving the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist. Second, icons of Christ depict him with a cruciform halo. This distinguishes Christ from the saints, who also have haloes. Third, icons of Christ typically have the Greek initials: “IS CS”, which stand for: “IesouS ChristoS” and the Greek: “O ΩN” which means: “Who Is,” a reference to the biblical phrase: “He who was, and who is, and who is to come” (Revelation 1:8). Furthermore, Orthodox icons typically have written on them the name of the saint depicted. With these safeguards, and living under the pastoral care of the local Orthodox priest, it is not likely for such an error to occur.

A Conversation About Icons

It is a common practice for Orthodox Christians to venerate the icon of Christ upon entering church on Sunday morning. A Protestant visiting an Orthodox church for the first time might have this conversation with his Orthodox friend:

Protestant Visitor: What did you just do? Why did you kiss that picture?

Orthodox Christian: I wanted to show my love and respect for Christ my Savior.

Protestant Visitor: But that’s just a picture!

Orthodox Christian: It’s more than a picture. An icon is like a window into heaven.

Protestant Visitor: So you’re not kissing a picture but Christ himself?!

Orthodox Christian: Yes. You got that right.

Protestant Visitor: That’s weird! Christ is up in heaven. He can’t be here in that picture.

Orthodox Christian: I guess that’s why you’re Protestant and I’m Orthodox. I believe Christ is up in heaven and in the icon. Christ is everywhere present.

The Disenchanted World of Modernity

Reformed Christians, and much of Protestantism, live in what Max Weber described as a “disenchanted world” of modernity (pp. 148, 155), where rational thinking prevails, and magic and mystery have been driven out. For this reason, Reformed Christians are willing to allow for icons as creative expressions or visual illustrations, but balk at icons as sacramental vessels of divine grace. This difference in worldview underlies the disconnect sketched in the dialogue above. Converts to Orthodoxy have abandoned Weber’s “disenchanted world” for an earlier Christian worldview, where creation is viewed as sacramental, charged with divine grace, and not mere matter. In Orthodoxy, common objects like olive oil, basil leaves, palm branches, are blessed and used to reveal God’s merciful presence, along with the water of baptism, and the bread and the wine of Holy Communion. In Orthodoxy, the redemption of fallen creation, or rather the reenchantment of the world, begins right here and now. In the Divine Liturgy, material creation is taken and blessed, and then offered up, or rather reintegrated with the kingdom of heaven. In the Liturgy, the kingdom of God is not something we hear about but rather a reality we encounter through the worship of the Holy Trinity.

Robert Arakaki

References

Eusebius of Caesarea. Church History. Book VII, Chapter 18.

Leonid Ouspensky. 1978. Theology of the Icon. Volume I. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Paul Evdokimov. 1990. The Art of the Icon: a theology of beauty. Translated by Fr. Steven Bigham. Oakwood Publications.

Theodore the Studite. 1981. On the Holy Icons. Translated by Catharine P. Roth. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Max Weber. 1946. “Science as a Vocation.” In From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, translators and editors. Oxford University Press.

Betsy Porter. Betsy Porter – Art and Iconography: Icons of Jesus and Scenes From His Life. Viewed 12 April 2016.

Columbia University. “Faith, Imagined – Early Christianity.”

Howard Jacobson. “Behold! The Jewish Jesus.” The Guardian.

“Faces of Jesus: Forensic Image.” [Depiction of Jesus by Richard Neave.]

Christopher Jones. “The Letters of Abgar V.” The Gates of Nineveh.wordpress.com

Wikipedia. “Depictions of Jesus.” Viewed 12 April 2016.

Recent Comments