Icon – St. Nicholas of Myra

One of the unexpected blessings of becoming Orthodox is discovering a Christian heritage forgotten in the West. One example of this is St. Nicholas of Myra, the original Santa Claus. He is well known in the Orthodox Church. Every December 6 the Orthodox celebrates the life of St. Nicholas of Myra. When I was a Protestant Evangelical I was barely aware of the historical St. Nicholas, but soon after I became Orthodox I became quite familiar with this popular saint.

St. Nicholas lived in the fourth century on the southwestern coast of Asia Minor (present day Turkey). He lost his parents when he was young and was raised by uncle also named Nicholas who was bishop of the town of Patara. In time he was ordained to the priesthood and became a bishop. He was present at the Council of Nicea and was reputed to have been so incensed by Arius’ blasphemy against Christ that he went up and slapped Arius in the face. One well known story tells how St. Nicholas would secretly throw a purse of gold into the home of a poor man with three daughters. The gold provided the dowry that enabled them to marry and prevent them from resorting to prostitution.

In modern American society everyone knows about “Santa Claus” the jolly old man who lives in the North Pole and comes out every Christmas Eve to deliver presents to good children everywhere. Virtually every American child today has paid a visit to Santa at the mall where they are gently questioned whether they have been good this past year. After a gentle scolding and encouragement to do better the child is sent back with an implied promise of something good coming their way.

This raises the question how did St. Nicholas become Santa Claus? And how did Western Christianity come to have such a divergent view of this great Christian saint?

From Dutch “Sinterklaas” to American “Santa Claus”

Sinterklaas in the Netherlands

Sinterklaas was part of the Dutch culture. Every year on December 6 in the Netherlands a town resident would dress as Sinterklaas – elegantly garbed with a bishop’s miter, red cape, shiny ring, and a jeweled staff. During the night Sinterklaas would ride his white horse through the town knocking on doors bringing goodies for the good children. He had a sidekick, Black Peter, the Grumpus – a wild looking half man, half beast – who threatened to take away the naughtiest children in his black bag, and for those not so naughty he had birch switches as lesser punishments. Here we can see the resemblance between the Dutch Sinterklaas and the Eastern Orthodox St. Nicholas. The Dutch remembered him as a bishop just as the Orthodox do. The name Nicholas became altered into “Klaas.”

When the Dutch migrated to the New World they brought many of their traditions and customs with them. They first settled on the island of Manhattan and so it became known as New Amsterdam. When the British took control of the island, it was renamed New York. The British adopted the customs popular among the Dutch residents and often merged it with their own English customs like Winter Solstice and the jolly Father Christmas.

In the New World a kind of cultural assimilation and syncretism took place over several generations. The writer Washington Irving created a jolly Sinterklaas for his Knickerbocker Tales in 1809. Then in 1822, an Episcopalian priest named Clement Moore wrote a lighthearted poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” which soon became known by the opening line: “Twas the night before Christmas.” It is here that we find the origins of the Santa Claus familiar to modern day Americans. Moore’s poem depicts St. Nicholas as a jolly old elf with a long white beard and a pipe in his mouth. He drives a sleigh pulled by eight reindeers, flies through the air from house to house, and magically jumps down the chimneys to deliver presents to the children. What we see here is a dramatic mutation of a familiar Christian figure. This may seem harmless to Protestants who view extra-biblical traditions as non-essential to their faith but it also points to the untethering of American culture from its historic Christian heritage.

Dreaming of a White Christmas

Modern Santa Claus

Following the Great Depression and World War II, the US entered into a period of unprecedented economic affluence. The 1950s marked the emergence of a consumer society where mass consumption would be the engine of economic growth. It was during this period that Christmas underwent a significant secularization. Retailers began to look to the Christmas season as a time when sizable customer purchases would help them close out the year in the black. To ensure high sales volume manufacturers and retailers began to rely heavily on mass advertising in the print media, radio, and television. The message soon centered on Christmas as a season to be jolly and the giving of gifts to loved ones. Sometimes the message of giving to those less fortunate was also mentioned. There also came the message that if one got just the right present one would find happiness. But it soon became evident that Christmas had undergone a shift in meaning away from its historic Christian roots. Part of the reason for the blurring of the Christmas season’s religious content was the fear of alienating any segment of the market which would result in loss of potential sales.

Santa Claus as a Culture Myth

I wondered why Santa Claus was so much an integral part of American culture. More specifically, I wondered why grownups would purposefully lie to children about a fictional character who flies once a year delivering gifts to children everywhere. Why is this deception so embedded in modern American culture? Does it serve any particular function?

I believe the answer lies in viewing the modern Santa Claus as a culture myth. Every culture relies on stories to explain how the world works. The Santa Claus myth operates on two levels. For children he teaches them the need to be good even when there’s nobody around and he teaches them the joy of getting presents. Children also learn the lesson of self-restraint — one had to wait for the right moment before opening the presents.

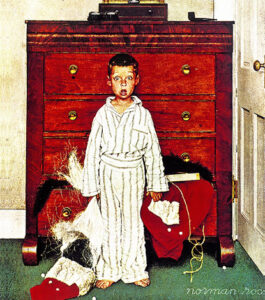

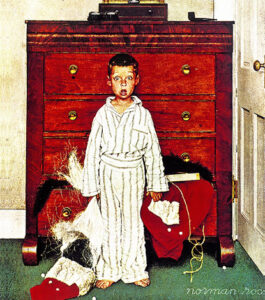

Santa Isn’t Real! by Norman Rockwell

For adults the Santa Claus myth teaches that as children we inhabit the world of faith and make believe but when we grow up we become conscious of the world as it really is. That is why the moment of realization that Santa is really Daddy is so important to the Santa Claus myth. The Santa Claus myth reenacts the emergence of modernity. Pre-moderns live in an enchanted world based upon blind faith; moderns live in a world based upon facts, scientific research, and rational calculation. The day the child realizes that Santa is Daddy marks a step towards adulthood with the subsequent loss of innocence and pure faith. It is fun to be a child but we must all grow up and face the facts. This classic scene captured by Norman Rockwell shows a “saucered-eyed” look on the boy’s face which Johns Hopkins University Professor Richard Halpern described as a “flash of youthful disillusionment. At this moment the question is planted in the boy’s mind, “What else are they lying about?” This question can create an attitude of skepticism which can lead to scientific investigation. It can also lead to an attitude that challenges authoritarian claims to truth. When they have children, many grownups reenact the Santa Claus myth, not only because it is part of popular culture, but also because doing so enables them to recapture the innocence and magic of childhood.

Counter-Cultural Orthodoxy

As Christmas became increasingly depleted of its religious and Christian content, many Christians, especially conservative Evangelicals, became uneasy. They would counter with slogans like: “Putting Christ Back into Christmas” and “Jesus is the Reason for the Season.” This led me to wonder why Evangelicals are so concerned about this.

I suspect that unlike high church traditions that have a strong sense of the visible church, Evangelicalism’s low church ecclesiology has resulted in the public space functioning as the equivalent of the visible church. The church is not just a weekly sermon, songs, and a building; it is a way of life, that is, a culture. For a long time Evangelicals in America relied on popular culture for the visible expression of their faith. This would explain their often shrill insistence: “America was founded as a Christian country!” It would also explain Evangelicals’ obsession with crossover hits in music and movies. The dream for many Evangelicals is a bestselling novel, record, or movie among both the born again Christians and general population. By means of these bestsellers they witness to America about Jesus and help millions make a decision for Christ. The dream of many Evangelicals is a spiritual revival or awakening that sweeps the nation restoring America as a Christian nation.

Lacking a historically grounded theological framework Evangelicalism finds itself drifting and shifting in multiple directions in recent days. Trevin Wax in his blog Kingdom People recently published a four part series “What Is An Evangelical?” The recent discussions shows that Evangelicals have no unified stance towards popular society, some take a defensive stance while others take a more open and embracing stance.

Unlike Evangelicalism which assumed the public space to be its birthright, Orthodoxy’s experience in America has been that of an obscure religion. While Orthodoxy enjoys official standing in the old countries, it also has memories of the time when it was a persecuted and illegal religion under Roman rule. With its well defined structures and sense of Tradition, Orthodoxy is in a much better position to deal with the drift to a post-Christian America than the Evangelicals. The Orthodox Church has the resources to maintain a culture within culture much more effectively than many Evangelical churches.

Remembering St. Nicholas in Grand Rapids, Michigan

St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church – 2009

The Grand Rapids Press published an article written by Andrew Ogg which describes how the members of St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church celebrated the life of their patron saint.

GRAND RAPIDS — Children tagged behind brightly dressed clergymen as they carried an illustration of Saint Nicholas and one of his bone fragments in a box.

Parishioners crossed themselves as the celebratory procession wound around pews, with the smell of incense filling Saint Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church, 2250 E. Paris Ave. SE last Sunday.

No reindeer. No toy-filled sleigh. No jolly old elf with a sweet tooth. This kindly gift giver was — kids, cover your eyes — real.

“The typical department store Santa, he’s quite a long way from the historical saint,” said Father Daniel Daly, pastor at Saint Nicholas.

Still, Daly doesn’t begrudge youngsters their Christmas wish lists.

“It’s a fun time for the kids,” he said. “I don’t see it as particularly bad or dangerous or anything. As long as people get to the real celebration of what is truly the center of Christmas, of course, and that’s the mystery of the incarnation.”

For more about how this particular parish maintains an Orthodox perspective on Christmas click here.

The lesson here is that while counter-cultural, Orthodoxy is not necessarily hostile to American culture as a whole. We take what is good and beneficial in our culture and try to correct what is lacking or misleading. We do this because we see culture as a gift from God.

Celebrating the Life of St. Nicholas

For those concerned about the post-Christian drift Orthodoxy provides resources for resisting this drift. One important means is the Christmas fast (I’ll write about this another time), another is the celebration of the life of St. Nicholas. On December 6 the Orthodox Church commemorates the life of St. Nicholas. For the Orthodox this is not an option but part of our liturgical calendar. We do this because it is part of the Tradition of the Church to remember its saints.

The historical memory of the Church is embedded not so much in books as in its liturgical life. Through these liturgical celebrations the Orthodox learn about the heroes of the faith. An examination of the Akathist (hymn/prayer) to St. Nicholas shows the Orthodox approach to commemorating the life of a saint. Thus singing in the choir is a great way to learn the Orthodox faith.

Kontakion 1

O champion wonderworker and superb servant of Christ

thou who pourest out for all the world

the most precious myrrh of mercy

and an inexhaustible sea of miracles

I praise thee with love, O Saint Nicholas;

and as thou art one having boldness toward the Lord,

from all dangers do thou deliver us,

that we may cry to thee:

Rejoice, O Nicholas, Great Wonderworker!

In the first kontakion (hymn in verse form) St. Nicholas is remembered as a servant of Christ who went about doing good to others. It also shows how Orthodoxy understands the communion of saints. St. Nicholas is understood to be very much alive and in the presence of God. He is part of the invisible company of saints in heaven who are praying for us.

Ekos 2

Teaching incomprehensible knowledge about the Holy Trinity,

thou wast with the holy fathers in Nicea

a champion of the confession of the Orthodox Faith;

for thou didst confess the Son equal to the Father,

co-everlasting and co-enthroned,

and thou didst convict the foolish Arius.

Therefore the faithful have learned to sing to thee:

Rejoice, great pillar of piety!

Rejoice, city of refuge for the faithful!

Rejoice, firm stronghold of Orthodoxy!

Rejoice, venerable vessel and praise of the Holy Trinity!

Rejoice, thou who didst preach the Son of equal honour with the Father!

Rejoice, thou who didst expel the demonized Arius from the council of the saints!

Rejoice, father, glorious beauty of the fathers!

Rejoice, wise goodness of all the divinely wise!

Rejoice, thou who utterest fiery words!

Rejoice, thou who guidest so well thy flock!

Rejoice, for through thee faith is strengthened!

Rejoice, for through thee heresy is overthrown!

Rejoice, O Nicholas, Great Wonderworker!

In Ekos 2 (earnest request) St. Nicholas is remembered for being at the Council of Nicea which resulted in the affirmation of Christ’s divinity. Where Kontakion 1 remembers St. Nicholas for his deeds of charity, Ekos 2 remembers his defense of right doctrine. Here the Orthodox faithful are given both a history lesson and a lesson in Christology.

Conclusion

The liturgical life of the Orthodox Church helps the Orthodox faithful to resist being conformed to the ways of the world. If we are faithful in our participation in the liturgical life of the Church and attentive to what is being sung we will be rooted in the Orthodox Faith. There is a stability and rootedness in Orthodoxy that Evangelicals and Protestants can learn from.

Let us remember the real St. Nicholas and let us seek to be imitators of great saints like St. Nicholas of Myra in this Christmas season.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments