Recently, a new form of worship has become widely popular among Christians. Where before people would sing hymns accompanied by an organ then listen to a sermon, in this new worship there are praise bands that use rock band instruments, short catchy praise songs, sophisticated Powerpoint presentations, and the pastor giving uplifting practical teachings about having a fulfilling life as a Christian. This new kind of worship is so popular that people come to these services by the thousands. They go because the services are fun, exciting, easy to understand, and easy to relate to. This new style of worship is light years away from the more traditional and liturgical Orthodox style of worship. How does an Orthodox Christian respond to this new worship? Is it acceptable or is it contrary to Orthodoxy? How should an Orthodox Christian respond to an invitation to attend these contemporary Christian services?

According to the Pattern

First we need to ask: Is there a guiding principle for right worship? St. Stephen, the first martyr, gave a sermon about the history of the Jewish nation. In this sermon he notes that Old Testament worship was “according to the pattern.”

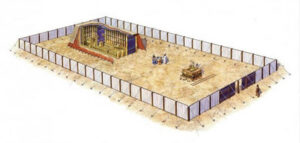

Our forefathers had the tabernacle of the Testimony with them in the desert. It had been made as God directed Moses, according to the pattern he had seen. (Acts 7:44 NIV, italics added).

This phrase comes up again in the book of Hebrews.

They serve at a sanctuary that is a copy and shadow of what is in heaven. This is why Moses was warned when he was about to build the tabernacle: “See to it that you make everything according to the pattern shown you on the mountain.” (Hebrews 8:5 NIV, italics added)

The phrase is a reference to Exodus 24:15-18 when Moses went up on Mt. Sinai and spent forty days and forty nights up there. On Mt. Sinai Moses was in the direct presence of God receiving instructions about how to order the life of the new Jewish nation. Thus, the guiding principle for Old Testament worship was not creative improvisation nor adapting to contemporary culture but imitation of the heavenly prototype.

The next question is: What is the biblical pattern for worship? In Exodus 25 to 31, Moses received instruction concerning the construction of the Ark of the Covenant, the Tabernacle, the lamp stand, the altar for burnt offerings, the altar for incense, the anointing oil, the vestments for the priests, and the consecration of the priests. The principle of “according to the pattern” was repeated several times in the design specifications for the Tabernacle (Exodus 25:8, 25:40, 26:30, 27:8). This was the template for the spiritual identity of the Jewish people. To be a faithful Jew meant that one offered to Yahweh the proper sacrifices in the prescribed manner.

Despite the clearly laid out instructions in Exodus and Leviticus, the Israelites struggled to keep to the biblical pattern of worship. The struggle to maintain the right worship of Yahweh in the face of temptations to follow the idolatrous ways of the non-Jewish nations is a theme running through Old Testament history. The sin of the golden calf in Exodus 32 was not the sin of heresy (wrong doctrine), but the sin of false worship. When the northern tribes broke from Judah, Jeroboam did not create a new theology, instead he had two golden calves made and appointed non-Levites to be priests as a way of consolidating his rule (II Kings 12:25-33). II Chronicles is a history of the struggle to maintain fidelity to Yahweh by holding to the biblical worship. II Chronicles 21 to 24 relates how a bad king — Jehoram — led the Israelites astray through Ba’al worship and a good king — Josiah — brought them back through the restoration of the Passover sacrifice. Apostasy in Old Testament times meant abandoning Yahweh for other gods and the chief means was the sin of idolatry (wrong worship). The lesson here is that right worship was critical for a right relationship with God.

Thus, orthodoxy — right worship — in the Old Testament meant keeping to the pattern of worship that Yahweh revealed to Moses on Mt. Sinai. Right worship was also key to Israel’s covenant identity. This suggests that right worship is key to our Christian identity. By studying how worship was defined in the Old Testament and comparing it with the Orthodox liturgy we can better understand why Orthodox worship is the way it is and how contemporary worship has strayed far from biblical worship.

Where Does Orthodox Worship Come From?

Worship in the Orthodox Church is patterned after the Old Testament Temple. Typically, an Orthodox church has three main areas: the narthex (entry hall), the nave (the central part), and the altar area. This is similar to the Old Testament Tabernacle which consisted of the Outer Court, the Holy Place, and the Most Holy Place (Exodus 26:30-37, 27:9-19; I Kings 6:14-36; II Chronicles 3 and 4). The layout of Orthodox churches may seem strange to those who attend contemporary services, but it is patterned after the Old Testament Temple. As a matter of fact, Orthodox church buildings are often referred to as temples.

When we enter into an Orthodox Church we are entering into sacred space much like the Old Testament Tabernacle. When I go to an Orthodox church on Sunday, I enter into the narthex, a small entry room. I light a candle in front of the sacred image of Jesus Christ and commit my life to Christ in preparation for worship. The short time I spend in the narthex helps me to shift my mind from the world outside to the heavenly worship inside.

Then I enter into the nave, the large central part of the church building where the congregation gathers for worship. All around me I see sacred images of Christ, the saints, and the angels. This is patterned after the Jewish Temple which had images of angels, trees, and flowers carved on the walls (I Kings 6:29; II Chronicles 3:5-7). Up in the front is a wall of sacred images (the iconostasis). In the middle of this wall is a door with a gate across it. This wall of images is patterned after the curtain that separated the Holy Place from the Most Holy Place in the Jewish Temple (Exodus 26:31-33; I Kings 6:31-35). Behind this is the altar area where the Eucharist is celebrated. Just as the Jewish high priests offered sacrifices in the Most Holy Place at the Jerusalem Temple, the Orthodox priests offer up the spiritual sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood at the altar. The altar area also symbolizes Paradise, the Garden of Eden, where Adam and Eve enjoyed deep communion with God before the Fall. We receive Holy Communion in front of the altar reminding us that we have been restored to communion with God through Jesus’ sacrificial death on the cross.

Orthodox worship is also patterned after the worship in heaven. At the start of the second half of the Divine Liturgy the church sings:

Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord of Hosts, heaven and earth are full of your glory. Hosanna in the highest. Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.

This is a participation of the heavenly worship described in Isaiah 6:3 and Revelation 4:8. For the Orthodox Church this point of the Divine Liturgy is not so much an imitation as a participation in the heavenly worship.

Another way Orthodox worship is patterned after the heavenly worship is the use of incense. Incense was very much a part of the heavenly worship. In his vision of God, Isaiah describes how as the angels sang: “Holy, Holy, Holy” the doors shook and the temple in heaven was filled with incense (Isaiah 6:4). The Apostle John in Revelation describes how the angels in heaven held bowls full of incense and how the heavenly Temple was filled with incense smoke (Revelation 5:8, 8:3-4, 15:8).

The vestments worn by Orthodox priests are patterned after the Old Testament and the heavenly prototype. The entire chapter 28 in Exodus contains instruction on the making of priestly vestments. In heaven, Christ and the angels wear the priestly vestments (Revelation 1:13, 15:6). The vestments are more than pretty decorations, rather they are meant to manifest the dignity and the beauty of holiness that adorns God’s house.

Old Testament Prophecies of Orthodox Worship

Orthodox worship is more than an imitation of Old Testament worship. It is also a fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecies. The Old Testament prophets besides describing the coming Messiah also described worship in the Messianic Age. Within the book of Malachi is a very interesting prophecy:

My name will be great among the nations, from the rising to the setting of the sun. In every place incense and pure offerings will be brought to my name, because my name will be great among the nations, says the Lord. (Malachi 1:11)

The phrase “from the rising to the setting of the sun” is a poetic way of saying from east to west — everywhere. Here we have a prophecy that the worship of God which was formerly confined to Jerusalem would in the future become universal. This was confirmed by Jesus in his conversation with the Samaritan woman at the well. In response to her question whether Jerusalem or Mt. Gerizim was the proper place for worship (John 4:19), Jesus answered that in the Messianic Age true worship would not depend on location but on worship of the Trinity. His statement about worshiping the Father in spirit (Holy Spirit) and truth (Jesus Christ) (John 4:23-24) is a teaching that true worship is worship of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

What is striking about Malachi’s prophecy is the reference to incense. Where before incense was offered in the Jerusalem Temple, in the Messianic Age incense would be offered by the non-Jews. One of the most vivid memories many first time visitors have of Orthodox worship is the smell of incense. Incense is burned at every Orthodox service. In the Roman Catholic Church incense is used in the high Mass but not in most services. Most Evangelical and Pentecostal churches do not use incense at all. Thus, whenever an Orthodox priest swings the censer and the sweet fragrance fills the church one experiences a direct fulfillment of Malachi’s prophecy. Protestants may complain about how strange incense is, but they should realize that the use of incense was an integral part of Old Testament worship and is one of the key markers of authentic biblical worship in the Messianic Age.

Malachi’s prophecy about “pure offerings” is a reference to the Eucharist. The Jewish rabbis taught that when the Messiah comes all sacrifices would be abolished with the exception of one, the Todah or Thanksgiving sacrifice. This was fulfilled in the sacrament of the Eucharist, that is, the last supper Christ had with his followers when he gave thanks over the bread and the wine (Luke 22:17-20). The word “eucharist” comes from the Greek word ευχαριστειν,”to give thanks.” Jesus’ statement about the cup of the new covenant meant that he was about to inaugurate the Messianic Age. The Eucharist is a remembrance of Christ’s death on the cross as well as a participation in Christ’s body and blood (I Corinthians 10:16-17). Thus, the Eucharist — the pure offerings — is another key sign of right worship in the Messianic Age.

In the last chapter of Hebrews is a strange verse that many Evangelicals and Protestants skip over:

We have an altar from which those who minister at the tabernacle have no right to eat (Hebrews 13:10; italics added).

What the author is asserting here is that the priests and Levites working at the Jerusalem Temple have no access to the Christian Eucharist. The Eucharist is only for those who confess Jesus as the promised Messiah and his death on the cross as the ultimate Passover sacrifice. The reference to the altar tells us the early Christians celebrated the Eucharist on real altars and that they had priests.

Protestants today have the habit of calling the platform area altars and spiritual songs as sacrifice. This involves a significant spiritualizing of the meaning of Hebrews 13:10. Furthermore, if we take this spiritualizing approach the phrase “have no right to eat” would not make sense. In the early Church if one did not confess Jesus as Christ, one could not receive the Eucharist. Contemporary Protestant worship on the other hand welcomes everybody and makes no distinction between believers and nonbelievers in its worship. In short, the early Church’s worship style was radically different from Protestant churches that have dispensed with the altar and the idea of the Eucharist as a spiritual sacrifice. To those who advocate contemporary worship, the Orthodox Christian can reply: We have an altar, where is yours?

An Evangelical or Charismatic visiting an Orthodox service might object to the Eucharist on the grounds that it is a re-presenting of Christ’s once and for all sacrifice. First of all, this argument comes from the Protestant debate against Roman Catholicism. Orthodoxy is not the same as Roman Catholicism. Second, the idea of the Eucharist as a re-presenting of Christ’s blood is contrary to the teachings of the Orthodox Church. In the Liturgy, the priest prays: “Once again we offer You this spiritual worship without the shedding of blood….” (Kezios p. 25; italics added)

For the Apostle Paul the Eucharist was just as important as the Gospel message. As he went about planting churches across the Roman Empire, Paul taught them the Good News of Jesus Christ and how to celebrate the Eucharist. This can be seen in Paul’s formal phrasing: “For I received from the Lord what I also pass on to you….” in I Corinthians 11:23 for the Eucharist and in I Corinthians 15:3 for the Good News (Gospel). Paul’s phrase: “What I received from the Lord….” parallels that in Exodus 25:9: “exactly like the pattern I will show you.” The infrequent celebration of the Eucharist in Evangelical and Pentecostal worship shows how far they have moved from historic Christian worship.

Another prophetic sign of worship in the Messianic Age is the priesthood. The last chapter of Isaiah contains a prophecy about the time when knowledge of Yahweh would become universal among the Gentiles and God would make priests of non-Jews.

And I will select some of them also to be priests and Levites, says the Lord. (Isaiah 66:21 NIV; italics added)

Part of this great ingathering would be the consecration of Gentiles to the priesthood. This was fulfilled when Jesus gave the Great Commission to the apostles (Matthew 28:19-20). Paul understood his work of evangelism as a “priestly duty” (Romans 15:16). In Isaiah is another prophecy about the important role that the Gentiles would play in the rebuilding of Israel, that of the establishment of the New Israel, the Church.

They will rebuild the ancient ruins

and restore the places long devastated;

they will renew the ruined cities

that have been devastated for generations.

Aliens will shepherd your flocks;

foreigners will work your fields and vineyards.

And you will be called priests of the Lord,

you will be named ministers of our God. (Isaiah 61:4-6 NIV; italics added)

Isaiah’s prophecy could be understood to refer to the Jews’ return from Babylon in 538 BC, but the fact that non-Jews would be part of the rebuilding process is an indication that the prophecy points to the coming of Christ. At the first Church council, St. James, the Lord’s stepbrother, quotes from the prophet Amos in defense of admitting non-Jews into the Church:

After this I will return

and rebuild David’s fallen tent,

Its ruins I will rebuild,

and I will restore it,

that the remnant of men may seek the Lord,

and all the Gentiles who bear my name,

says the Lord, who does these things

that have been known for ages. (Acts 15:16-17 NIV; Amos 9:11-12)

The key to understanding Isaiah’s prophecy about the priesthood is that a priest does not stand alone but in a certain context: temple, altar, and sacrifice. This pattern of priesthood, temple, and sacrifice can be found in I Peter 2:5:

…you also, like living stones, are being built into a spiritual house to be a holy priesthood, offering spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ (NIV).

The Apostle Peter reiterates the teaching that the Church is a “royal priesthood” in I Peter 2:9. This can be seen in the fact that the early Christians celebrated the Eucharist regularly on the first day of the week, Sunday. The early Christians understood the Eucharist to be a spiritual sacrifice and had priests to lead them in worship. Today, two thousand years later, the Orthodox Church still has priests standing at the altar offering the eucharistic sacrifice. Contemporary worship has none of these. Thus, Isaiah 61:6 finds its fulfillment in Orthodox worship, not contemporary worship.

Protestants may object to the Orthodox Church having priests on the grounds that because of Christ we have no need for a man to serve as a mediator with God. This objection is based upon a misunderstanding of the nature of Orthodox worship and the office of the priest. Basically, the priest’s role is to lead the congregation in worship. If one listens carefully to the litanies one finds the priest addressing the congregation, For … let us pray to the Lord, and the congregation responding with, Lord have mercy. In other words, the congregation prays with the priest, not through the priest. As a matter of fact, in Orthodoxy the priest cannot begin the Divine Liturgy unless the laity is present. This is based on the Orthodox Church’s understanding that the priesthood resides in the whole church, not just in the ordained clergy. The participation of the laity is just as critical for right worship as the clergy. This can be seen in the fact that “liturgy” comes from the Greek λειτουργεια, “leitourgeia,” which means worship and also the “work of the people.” Jesus Christ is our Mediator and he exercises that ministry through his office as the great High Priest. This means it is imperative that we be part of the Divine Liturgy and not off doing our own thing.

Protestants cite I Peter 2:5 as a repudiation of the priesthood. This reading of I Peter 2:5 relies on the illogical reasoning that since we are all priests, no one is a priest. The Protestant reading of I Peter 2:5 has resulted in churches without priests and no altars. Historically the Christian Church has recognized the offices of deacons, priests, and bishops. The practice of an ordained clergy has roots in the New Testament Church. We read in Acts 1:20, “Let another take his office” (NKJV, italics added; see also I Timothy 5:17-22, II Timothy 2:2). Where for over a thousand years Christianity had priests celebrating the Eucharist on altars, after 1500 there emerged a new form of Christian worship that disavowed the priesthood and removed the altar from the sanctuary.

Anyone who compares Orthodox worship with contemporary worship will be struck by how biblical Orthodox worship is and how far contemporary worship has moved away from the Old Testament pattern. When we take into consideration the Old Testament prophecies, the significance of liturgical worship in Orthodoxy becomes even more compelling. Orthodox worship follows the pattern of Old Testament worship and is the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. This is the worship God wants in this day and age.

Was Old Testament Worship Abolished?

The Evangelical approach to worship seems to be based on the assumption that Jesus abolished the Old Testament. Because of this Evangelicals ignore the Old Testament teaching on Tabernacle worship and focus on the New Testament for instruction on how to worship God. The paucity of New Testament passages on worship has been taken as grounds for an anything goes approach to worship. But, this assumption is wrong. Jesus made it clear he did not come to abolish the old covenant but rather to fulfill it:

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them (Matthew 5:17).

An examination of the gospels shows Jesus’ adherence to the Old Testament pattern of worship. Jesus was in the habit of attending the synagogue services (Mark 1:21; Mark 3:1; Mark 6:2). Likewise, he observed the great Jewish festivals at the Temple: Passover (Luke 2:41), Feast of Tabernacles (John 7:1-13), and Passover (Matthew 26:18; Mark 14:14; Luke 22:7-11). Like Jews throughout history, Jesus considered the Passover meal the highlight of the year. Jesus told his followers: “I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer.” (Luke 22:15)

In the healing of the leper we find an affirmation of Jewish Temple worship. After healing a leper, Jesus orders him:

But go, show yourself to the priest and offer the sacrifices that Moses commanded for your cleansing, as a testimony to them (Mark 1:44; Matthew 8:4).

Here we find Jesus affirming: (1) the Mosaic Law, (2) the Aaronic priesthood, and (3) the offering of sacrifices at the Temple. Nowhere do we find Jesus or his apostles disregarding the Jerusalem Temple or the Jewish forms of worship; rather we find indications they affirmed the Jewish form of worship.

Likewise, we find Jesus’ apostles continuning the Old Testament pattern of worship. Following the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost, the first Christians met at the Temple courts (Acts 2:36). The Temple court was a focal point for the early Christians (Acts 5:20). The apostles preached the Good News in hope that the Jews would accept Jesus as the Messiah. Just as significant we find them relying on the ritual prayers used by Jews. This can be seen in the fact that a literal translation of Greek in Acts 2:42 would be “the prayers.” We find that Paul, like Jesus, attended the synagogue (Acts 13:5, 14; 14:1; 17:2, 19:8). Even when Paul had become a Christian he continued to make it his habit to attend the synagogue services: As his custom was, Paul went into the synagogue…. (Acts 17:2)

The Apostles of Christ showed a similar respect to the Jerusalem Temple. We read in Acts 3:1 that Peter and John attended the prayer services at the Jerusalem Temple. In his testimony to the Jews Paul recounts how God spoke to him while he was at the Jerusalem Temple praying (Acts 22:17). The positive regard Paul and the other Apostles had to the Jerusalem Temple can be seen in: (1) Paul’s eagerness to attend the Pentecost services in Jerusalem (Acts 20:16), (2) the Jerusalem Apostles advising Paul to take part in the purification rituals to show their loyalty to the Torah (21:22-25), and (3) Paul’s participation in the Temple rituals (Acts 21:26).

Where Evangelicals assume a sharp discontinuity between the Old and New Testaments, the Orthodox Church sees a strong continuity between the two. The Evangelicals’ assumption of a sharp discontinuity between the Old and New Testaments has led them to ignore the Old Testament teachings on worship. This disregard for the Old Testament is much like the early heresy of Marcionism. Orthodox Christian worship is based upon a radical continuity. As the Jewish Messiah Jesus Christ took the Jewish forms of worship and filled them with new content and meanings. Orthodox worship took the Jewish synagogue and Temple worship and made them Christocentric.

Where Does Contemporary Worship Come From?

The classic shape of Christian worship consists of two parts: the liturgy of the word and the liturgy of Holy Communion. This was the way all Christians worshiped until the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s when Martin Luther and his followers rebelled against the Roman Catholic Papacy. It should be kept in mind that over the years the Pope had introduced changes like the Filioque clause and the dogma of transubstantiation with the result that the Roman Catholic worship diverged from that of the early Church. The Protestant Reformers sought to reform the church but the result was not a return to the historic pattern of worship. The Protestant teaching “the Bible alone” resulted in the sermon becoming the center of worship. Priests were replaced by Bible expositors, and the altar was replaced by the podium. This marked a decisive break from the historic form of Christian worship.

But the break from historic worship did not end there. In the early 1800s a more emotional and expressive form of worship became popular on the American frontier. Then, in the early 1900s Pentecostalism emerged with its emphasis on the baptism in the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues, and other charismatic manifestations. Where mainstream Protestantism stressed sober singing and the rational reading of the Bible, Pentecostalism stressed ecstatic worship and experiencing the Holy Spirit. For a long time Pentecostals were relegated to the margins of Protestantism and were derided as “holy rollers.” Then in the 1950s Pentecostalism began make inroads among mainline Protestants, and in the 1960s among Roman Catholics. Less demonstrative and theologically more sophisticated, this movement came to be known as the charismatic renewal.

Pentecostalism was just one of three movements that would radically transform American Protestantism in the second half of the twentieth century. Just as influential on Protestant worship was pop music popularized by music groups like the Beatles. The pop culture of the 1960s shaped in profound ways the values and outlooks of the baby boomer generation. A cultural gap widened between the more traditional church services that relied on organs or pianos and had traditional hymns, and the more contemporary church services that used guitars and sang simpler and catchier praise songs. Many churches were split as a result “worship wars” — hymns and organs versus praise bands and praise songs.

The third influential movement was the church growth movement. Though less visible to the public eye, it influenced the way many pastors understood and ran the church. The church growth movement brought market analysis and business techniques to the way the church was run. With the introduction of the concept of the seeker friendly church, church worship moved away from edification of the faithful to evangelizing outsiders. Numerical growth was seen as proof of God’s blessing. This is exemplified by mega churches packed with thousands of enthusiastic worshipers. However, despite its good intentions the church growth movement introduced several serious distortions. Worship of God often became spiritual entertainment. The sermon shifted from an exposition of Scripture to selecting Bible verses to support teachings on how to live a fulfilling life. In seeking to tailor the Christian message to non-Christians many pastors have dumbed down their message with the result that many of their members know very little of the core doctrines. Just as troubling is the fact that many churches have become spiritual machines that rely more organizational techniques, high tech electronics, and social psychology than the grace of the Holy Spirit.

In short, Protestant Christianity has undergone a major uprooting as a result of the influence of Pentecostalism, contemporary Christian worship, and the church growth movement. As a result of this massive uprooting, Evangelicalism has become rootless. The uprooting of Evangelical worship has created an opening for many new teachings and new styles of worship. There have emerged fringe groups with strange worship practices like being slain in the Spirit, holy laughter, word of faith teachings, prayer walks, etc. Some may believe these new forms of worship may presage a great spiritual revival that will sweep the world but it could also be a sign of a spiritual collapse of Protestant Christianity.

What Would the Apostle Paul Think?

If the Apostle Paul were to walk into an Orthodox liturgy, he would immediately recognize where he was — in a Christian church. The key give away would be the Eucharist. This is because the Eucharist was central to Christian worship. In the days following the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost the early Christians met in homes and celebrated “the breaking of bread” (the Eucharist). Paul received his missionary calling during the celebration of the liturgy (Acts 13:2 NKJV). He made the celebration of the Eucharist a key part of his message to the church in Corinth (I Corinthians 11:23 ff.).

If Paul were to walk into a traditional Protestant service with the hymn singing, the reading of Scripture and the lengthy sermon he might think he was in a religious service much like the Jewish synagogue. He may not have much trouble accepting it as a kind of Christian worship service, although he might question their understanding of the Eucharist. However, if the Apostle Paul were to walk into a mega church with its praise bands and elaborate worship routine, he would likely think he was at some Greek play and seriously doubt he was at a Christian worship service. If the Apostle Paul were to walk into a Pentecostal service he would probably think he had walked into a pagan mystery cult that had no resemblance at all to Christian worship.

Why Orthodox Worship?

A non-Orthodox might ask: What difference does it make to God how we worship? The better question would be: What does the Bible teach about worship? Does the Bible teach it makes a difference how we worship God? The answer is God does care about the worship we offer Him. We read in I Peter 2:5:

…you also, like living stones, are being built into a spiritual house to be a holy priesthood, offering spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ (NIV, italics added).

This concern for proper worship goes all the way back to Leviticus 22:29:

When you sacrifice a thank offering to the Lord, sacrifice it in such a way that it will be accepted on your behalf (see also Leviticus 19:5) (NIV, italics added).

If we are instructed to offer “acceptable” sacrifices, this implies we can offer improper worship that will be rejected by God. We see this in Genesis 4:3-5 where Abel and Cain offered sacrifices to Yahweh, and one was accepted and the other rejected. It can also be seen in Leviticus 10:1-3 where Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, died because they offered unauthorized fire to Yahweh. In I Chronicles 13:8-10, Uzzah, a non-Levite, died because he touched the Ark of the Covenant that only Levites were allowed to handle (I Chronicles 15:11-15, Numbers 4:15). In II Chronicles 26:16-20, King Uzziah sought to offer incense to Yahewh, something only the priests could do, and suffered divine punishment. Thus, there are consequences for not offering right worship. In this day and age the consequence of wrong worship are less dramatic. To offer wrong worship is to be outside the Orthodox Church and unable to receive the Eucharist.

If salvation is about a right relationship with God then worship plays an important part in having a right relationship with God. Before the Fall Adam and Eve enjoyed unbroken communion with God; after the Fall they became alienated from God and mankind has suffered as a result. God has been at work throughout human history working to bring us back into fellowship with him. This work of restoration reached its climax with the coming of Christ (Hebrews 1:1-2). The author of Hebrews stresses that Jesus Christ is the High Priest of the New Covenant (5:7-10; 9:9-14) and as a result of His death on the cross we are able to enter into the Most Holy Place (Hebrews 10:19-25) and take our place in the heavenly worship (Hebrews 12:22-24). In Revelation 7 is a description of the great ingathering of the Jews and the Gentiles in worship at the throne of God.

Our ultimate destiny is not to be Bible experts but to have communion with God. This can be seen in a strange verse in Exodus 24:7: “…they saw God, and they ate and drank.” In ancient times, after a covenant was ratified, the ruler and his subjects would sit down for a common meal. Eating together was a sign of fellowship and their common life together. This verse finds its fulfillment in the Liturgy when we feed upon Christ’s body and blood in the sacrament of the Eucharist (John 6:53-56). The heavenly worship described in Revelation is not in some far off future but can be experienced in the Sunday liturgy in an Orthodox church. In Revelation 22:3 we read:

And there shall be no more curse, but the throne of God and of the Lamb shall be in it, and His servants shall serve Him. They shall see His face and His name shall be on their foreheads (NKJV).

The Greek word “serve” (λατρευειν) can also be translated “worship.” As we stand in worship facing the altar we behold the throne of God; this is because the altar, like theArk of the Covenant, is where God’s presence dwells. The phrase we shall see God “face to face” finds its fulfillment when we face the altar looking at the icon of Christ the Pantocrator (the All Ruling One). The icon is more than a religious picture, it is also a window into heaven. Lastly, “His name shall be on their foreheads” is fulfilled in the Orthodox sacrament of chrismation where the priest anoints the foreheads of converts with sacred oil forming the sign of the cross. Every Orthodox Christian has this spiritual seal on their forehead as a sign of their belonging to Christ.

Thus, it is not Orthodox worship that is so strange and different but contemporary worship. Orthodox worship only seems to be strange because it is not of this world. It is part of the worship of the eternal kingdom. We as Orthodox Christians need to appreciate what a precious gift God has given us in the Divine Liturgy. We should become fervent in our prayers and our commitment to following our God and Savior Jesus Christ. We need to recognize that much of the attraction of contemporary worship comes from the fact it has taken the best the world has to offer but in so doing it has abandoned the orthodox, or right worship, God wants from us. The best response an Orthodox Christian can make to an invitation to visit a contemporary worship service is: “Come and see!” Many people today don’t know about the Orthodox Divine Liturgy and are hungry for a real worship experience. They need someone to invite them and be ready to explain how the Orthodox liturgy is the true worship taught in the Bible.

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments