A skeptical reader wrote in response to my article “Evidence for Christ’s Descent into Hell”:

How do you get around the statement of Christ to the thief on the cross ?

Was that a lie or do you think Christ did not know where he was going?

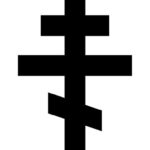

In all four Gospels we are told that Jesus was crucified along with two other men (Matthew 27:38; Mark 15:27-28; Luke 23:32, 39-43; John 19:18). But only in Luke’s Gospel do we learn about the dialogue that took place between Jesus and the two condemned criminals. The conversation is packed with spiritual significance. Even in his final moments Jesus has a profound impact on those around him. One man repents and returns to God. The other continues to reject God and ends his life unrepentant. This conversation is symbolized by the three-bar cross distinctive to the Slavic Orthodox tradition. The Slavic cross has three horizontal lines: a short horizontal bar symbolizing the sign proclaiming Jesus as King of the Jews, the long horizontal bar on which his hands were nailed, and a short diagonal bar symbolizing the board on which his feet were nailed. The diagonal line also symbolizes the contrasting destinies of the two thieves: one slanting upwards toward heaven and the other slanting downwards toward hell.

In all four Gospels we are told that Jesus was crucified along with two other men (Matthew 27:38; Mark 15:27-28; Luke 23:32, 39-43; John 19:18). But only in Luke’s Gospel do we learn about the dialogue that took place between Jesus and the two condemned criminals. The conversation is packed with spiritual significance. Even in his final moments Jesus has a profound impact on those around him. One man repents and returns to God. The other continues to reject God and ends his life unrepentant. This conversation is symbolized by the three-bar cross distinctive to the Slavic Orthodox tradition. The Slavic cross has three horizontal lines: a short horizontal bar symbolizing the sign proclaiming Jesus as King of the Jews, the long horizontal bar on which his hands were nailed, and a short diagonal bar symbolizing the board on which his feet were nailed. The diagonal line also symbolizes the contrasting destinies of the two thieves: one slanting upwards toward heaven and the other slanting downwards toward hell.

Sadly, many Protestant all too casually reject, without having done any study or attempting to understand, the ancient declaration of Christ’s descent into hell found in the Apostles Creed. The skeptical reader disagreed with my article about Jesus spending three days in hades before his Resurrection. He asks how this could be true in light of Jesus’ promise that the penitent thief would be with him in paradise that same day. This question is based on the assumption that paradise is synonymous with heaven, the spirit realm above, and that hades is the underworld where the dead repose. That being the case, if paradise is synonymous with heaven then it would be a logical contradiction for Jesus to be in heaven and hell that same time.

Is Paradise a Place or Life with Christ?

The reader’s skepticism appears to be based on the assumption that paradise is strictly a place. However, one must also consider the possibility that paradise can indicate being in a relationship with Christ. The Orthodox Study Bible (OSB) in the commentary notes for Luke 23:39-43 noted that the two thieves represent two different spiritual conditions. One thief refused to take responsibility for his actions, while the other acknowledged this guilt and asked Jesus to remember him. The commentary note states:

To be reconciled to Christ is to be in paradise immediately. Furthermore, the souls of the departed are in the presence of God and experience a foretaste of His glory before the final resurrection.

The popular Evangelical NIV Study Bible in the commentary for Luke 23:43 notes that “paradise” referred to the place of bliss and rest between death and resurrection. In the commentary for 2 Corinthians 12:4, the NIV Study Bible notes that “paradise” is synonymous with the third heaven, the place where the believers who have died are now “at home with the Lord.” Here we see the different emphases the two traditions have in their understanding of paradise.

Paradise in the Bible

In the Old Testament, the word “paradise” has been used several times in reference to the Garden of Eden, either directly or retrospectively. In the Septuagint version of Genesis 2, the word “παράδεισον” is used five times (verses 8, 9, 10, 15, and 16). The word appears again in Genesis 13 in which Sodom and Gomorrah—before the divine judgment—are likened to “the garden of God.” The Prophet Ezekiel used “paradise” in chapters 28 and 31 in his prophecies against the rulers of Tyre and Egypt. He invoked Eden, the “garden of God,” to depict the ruler being like Adam—in a state of perfection—before succumbing to the sin of pride which led to his downfall thereby incurring divine judgment.

In the Septuagint, paradise was used to evoke memories of Eden, a lush green enclosed garden in contrast to an unruly or devastated desert wasteland. In Joel 2:3, Zion is likened to a “paradise of splendor” (OSB) or a “garden of Eden” (RSV) (“ὡς παράδεισος τρυφῆς” in LXX). In Isaiah 51:3, Yahweh promises the Jews that he would one day restore Zion and make her like the “garden of the LORD” (“ὡς παράδεισον κυρίου” in LXX). Thus, the word “paradise” signifies mankind’s original condition of bliss and union with God before the Fall, not in a spiritualized gnostic sense, but in a uniquely agrarian reference to place. In the rabbinical literature, the bliss of paradise is contrasted with the torment of gehenna.

Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament notes that paradise has been understood by the Jews as referring to the First Age and to the Age to Come. Jewish eschatology anticipated a reopened or restored paradise.

The site of reopened Paradise is almost without exception the earth, or the new Jerusalem. Its most important gifts are the fruits of the tree of life, the water and bread of life, the banquet of the time of salvation, and fellowship with God. The belief in resurrection gave assurance that all the righteous, even those who were dead, would have a share in reopened Paradise. (TDNT Volume V, p. 767)

The notion of paradise as a future state can be found in Revelation 2:7 in which Jesus promises to those who overcome will eat of the Tree of Life that is in “paradise of God” (NA28). The commentary note in the Orthodox Study Bible informs us that the Tree of Life is an allusion to the Cross, the fruit is spiritual food, i.e., the Eucharist, and that the paradise of God is heaven.

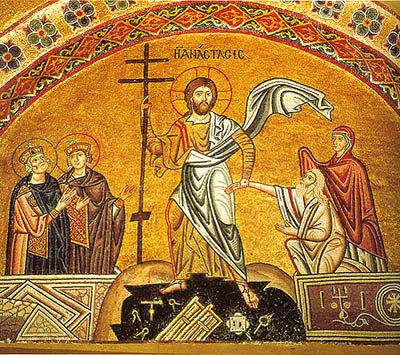

The promise of reopened paradise finds its fulfillment in the Orthodox Liturgy. The altar area of Orthodox churches is marked off by an icon wall (iconostasis) and the royal doors. When the doors are closed, they symbolize man’s expulsion from the original paradise, and when the gates are opened, they symbolize mankind being welcomed back to paradise. The Tree of Life is symbolized by the Cross and his body hanging on the Cross symbolizes the Fruit that conveys eternal life to those who partake of it. The Eucharist in which we feed on Christ’s Body and Blood symbolizes the Messianic banquet in which humanity is reconciled with God in the reopened paradise. For the Orthodox Christian this is a here-and-now reality that takes place every Sunday at the Eucharist, not in some far off future.

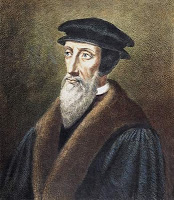

John Calvin’s Interpretation of the Good Thief

Calvin’s interpretation of Luke 23:39-43 can be found in his commentary on the synoptic Gospels (Vol. III pp. 200-205). Calvin has a lot to say about these five verses. He describes the Good Thief’s conversion as a miracle.

In this wicked man a striking mirror of the unexpected and incredible grace of God is held out to us, not only in his being suddenly changed into a new man, when he was near death, and drawn from hell itself to heaven, but likewise in having obtained in a moment the forgiveness of all the sins in which he had been plunged through his whole life, and in having been thus admitted to heaven before the apostles and first-fruits of the new Church.

Calvin underscores the fact that the Thief’s conversion was not a result of natural processes but the result of divine grace.

For it was not by the natural movement of the flesh that he laid aside his fierce cruelty and proud contempt of God, so as to repent immediately, but he was subdued by the hand of God; as the whole of Scripture shows that repentance is His work (Bold added).

Calvin used the Good Thief as evidence against medieval Catholicism’s elaborate soteriology which involved indulgences, the keys of Peter, and confession to lessen the amount of time one would spend in purgatory. For Calvin all that matters for entrance into heaven is faith and repentance.

Thus, when the robber has been brought by fatherly discipline to self-denial Christ receives him, as it were, into his bosom, and does not send him away to the fire of purgatory.

We ought likewise to observe by what keys the gate of heaven was opened to the robber; for neither papal confession nor satisfactions are here taken into account, but Christ is satisfied with repentance and faith, so as to receive him willingly when he comes to him.

Surprisingly, Calvin did not attempt to discuss the location of paradise. He seems to be suggesting that paradise consists of a state of bliss contingent on faith in Christ.

Today shalt thou be with me in paradise. We ought not to enter into curious and subtle arguments about the place of paradise. Let us rest satisfied with knowing that those who are engrafted by faith into the body of Christ are partakers of that life, and thus enjoy after death a blessed and joyful rest, until the perfect glory of the heavenly life is fully manifested by the coming of Christ (Italics in original; bold added).

Given Calvin’s reticence to discuss the location of paradise, our skeptical Protestant reader should not be overly concerned about reconciling the Good Thief’s entrance into paradise with Christ’s descent into hell. Many of the difficulties can be avoided if one focuses on the bliss of paradise stemming from relationship with Christ, not exclusively on the coordination of spatial locations. After all, it is Christ himself that is the bliss of paradise. We need a Christ-centered understanding of paradise and heaven, or else we will end up with a religious caricature of Disney World.

The Good Thief in the Orthodox Liturgy

When I converted to Orthodoxy I was surprised by how often I heard about the Good Thief. As a Protestant I hardly heard about the Good Thief with the exception of theological debates about death bed conversions and how the Good Thief provided an example of salvation without works and the possibility of being saved apart from being baptized. As an Orthodox Christian I am reminded of the Good Thief every Sunday in the closing line of the pre-Communion prayer:

O Son of God, receive me today as a partaker of Your mystical supper. For I will not speak of the mystery to Your enemies, nor will I give You a kiss, as did Judas. But like the thief, I confess to You: Remember me, Lord, in Your Kingdom.

One time I became especially aware of this line in the pre-Communion prayer. This was after my house had been broken into and I felt angry enough to punch the burglar in the face. Saying this prayer before going up for Holy Communion made me keenly aware that I was no better than the thief hanging on the cross.

Learning from the Early Church

Theophilus, the twenty-third Pope of Alexandria (ruled 384-412), gave the homily “On the Crucifixion and the Good Thief.” In the passage below, Theophilus constructs a dialogue between Christ and the Thief:

The gate of Paradise has been closed since the time when Adam transgressed, but I will open it today, and receive you in it. Because you have recognised the nobility of my head on the cross, you who have shared with me in the suffering of the cross will be my companion in the joy of my kingdom. You have glorified me in the presence of carnal men, in the presence of sinners. I will therefore glorify you in the presence of the angels. You were fixed with me on the cross, and you united yourself with me of your own free will. I will therefore love you, and my Father will love you, and the angels will serve you with my holy food. If you used once to be a companion of murderers, behold, I who am the life of all have now made you a companion with me. You used once to walk in the night with the sons of darkness; behold I who am the light of the whole world have now made you walk with me. You used once to take counsel with murderers; behold, I who am the Creator have made you a companion with me. (Bold emphasis added.)

Theophilus seem to understand paradise more in terms of a restored relationship with God than as a place. Where Calvin understood the Thief’s conversion as a result of divine intervention hinting at irresistible grace, Theophilus echoed the early consensus that even after the Fall humanity retained the ability to freely respond to God’s grace, as evidenced by the phrase “of your own free will.”

He continues exegeting the Good Thief’s confession from the standpoint of Matthew 10:32-33:

All these things I will pardon you because you have confessed my divinity in the presence of those who have denied me. For they saw all the signs which I performed, but did not believe in me. You, then, a rapacious robber, a murderer, a brigand, a swindler, a plunderer have confessed that I am God. That is why I have pardoned your many sins, because you have loved much (Lk. 7:47). I will make you a citizen of Paradise. I will wash you [sic] body so that it will not see corruption before I resurrect it with me on the third day and take you up with me.

Pope Theophilus continues his sermon contrasting the Unrepentant Thief against the example of the Good Thief. The bliss of the Good Thief is contrasted with the woes of the Unrepentant Thief. Unlike many Protestants who assume hell to be exclusively a place of fiery torment, Theophilus understands that hell also can be a frigidly cold place.

The other who has denied me will see you enveloped in glory, but he will be enveloped in pain and same. He will see you surrounded by light, but he will be surrounded by darkness. He will see you in a state of joy and happiness, but he will be in a state of weeping and groaning. He will see you enjoying ease and benediction, but he will be suffering oppression and malediction. He will see you refreshed by the angels, but he will be troubled by the powers of darkness. And in the midst of intense cold the worm that never rests will consume him. Not only did he not confess me, but after having denied me he reviled me. (Bold emphasis added)

‘For this reason all will receive according to their works. For as I have already said to them explicitly and in public: Everyone who acknowledges me before men, I will also acknowledge before my Father who is in heaven; but whoever denies me before men, I also will deny before my Father who is in heaven.’ (Mt. 10:32-33)

Reflecting on the Cross

In closing, it is important that we go beyond the Protestant versus Orthodox polemics and look to the wisdom of the early Church. The early Church can be viewed as common ground for both Protestants and Orthodox. The Cross of Christ is rich in symbolic meanings. Pope Theophilus, who lived in the fourth and fifth centuries, skillfully unpacked the meanings of the Cross of Christ.

Whether you are a Western Christian who just celebrated Easter or an Orthodox Christian looking forward to the Resurrection Service this coming Saturday evening, I encourage you learn from this early Christian bishop-preacher.

The cross is the consolation of those who are afflicted by their sins. The cross is the straight highway. Those who walk on it do not go astray. The cross is the lofty tower that that gives shelter to those who seek refuge in it. The cross is the sacred ladder than raises humanity to the heavens. The cross is the holy garment that Christians wear. The cross is the helper of the wretched, assisting all the oppressed. The cross is that which closed the temples of the idols and opens the churches and crowns them. The cross is that which has confounded the demons and made them flee in terror. The cross is the firm constitution of ships admired for their beauty. The cross is the joy of the priests who dwell in the house of God with decorum. The cross is the immutable judge of the apostles. The cross is the golden lampstand whose holy cover gives light. The cross is the father of orphans, watching over them. The cross is the judge of widows, drying the tears of their eyes. The cross is the consolation of pilgrims. The cross is the companion of those who are in solitude. The cross is the ornament of the sacred altar. The cross is the affliction of those who are bitter. The cross is our help in our hour of bodily need. The cross is the administration of the demented. The cross is the steward of those who entrust their cares to the Lord. The cross is the purity of virgins. The cross is the solid preparation. The cross is the physician who heals all maladies.

Wishing all of you a blessed Pascha!

Robert Arakaki

References

John Calvin. Calvin’s New Testament Commentaries: Matthew, Mark and Luke (Vol. III). David W. Torrance and Thomas F. Torrance, editors.

John Chrysostom. Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North America.

Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament: Volume V .

Theophilus. “Homily of Theophilus of Alexandria: The crucifixion and the Good Thief.” In Christian Forums. Posted by ‘Anglian’ 5 April 2010.

Recent Comments