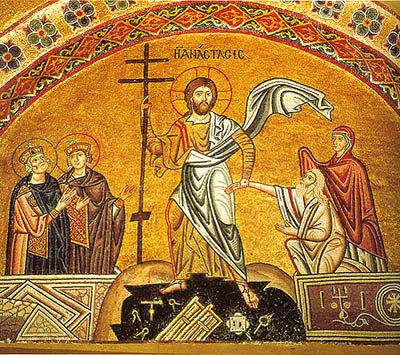

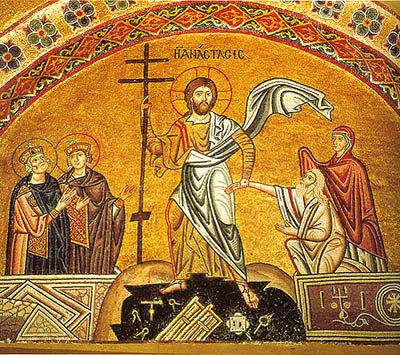

Christ standing over the shattered doors of Hell and rescuing Adam and Eve

On Holy Saturday, the Orthodox Church celebrates Christ’s descent into Hell (Hades). For many Protestants and Evangelicals this is a strange idea. When I was a Protestant, I was often puzzled by the line in the Apostles Creed: “he [Christ] descended to hell.” I thought this line was bizarre and unnecessary. As a Protestant, I was never taught the theology behind the historic creeds of the Church. However, after attending the Orthodox Easter (Pascha) services I began to see how Christ’s descent into Hell is important for our salvation.

Recently, the Rev. Scot McKnight wrote an insightful article “Holy Saturday: What Happened on Saturday to Jesus?” In it he listed bible verses that taught Christ’s descent into Hell. The article helped me to understand familiar passages in a new light. I thought I knew the Bible pretty well, but I was surprised to find that I had overlooked bible passages that support Holy Saturday, a feast day that takes place just before Easter Sunday. Thank you, Pastor McKnight! In this article, I examine the biblical basis for Christ’s descent into Hell, the witness of the Church Fathers to this doctrine, and John Calvin’s rejection of this important doctrine.

Icon – Jonah and the Whale

What the Bible Teaches

Christ’s descent into Hell (Hades, Sheol) can be found in both the Old and New Testaments. It forms a part of the arc of biblical narrative of how God saves us through Jesus Christ. Hell can be understood as the holding place where the souls of the good and the bad went after death (Luke 16:19-31). It is to be distinguished from Gehenna, the place of eternal torment (Mark 9:42-48; Revelation 20:14).

Christ’s descent into Hades was anticipated by Jesus himself in Matthew’s Gospel.

For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.” (Matthew 12:40: OSB; emphasis added)

Here Jesus saw in the Prophet Jonah’s three nights in the whale a foreshadowing of what would happen to him in his impending death.

The Apostle Peter spoke of Jesus’ descent into Hell in his Pentecost sermon:

He [David], foreseeing this, spoke concerning the resurrection of the Christ, that His soul was not left in Hades, nor did His flesh see corruption. (Acts 2:31; OSB; emphasis added)

Here Peter was making reference to Psalm 16 verse 10, one of the messianic psalms. One of the greatest concerns expressed throughout the Book of Psalms is the fate of the souls after death. In this passage we learn that death is not the final word and see hints of the Messiah’s victory over death.

The Apostle Paul in his letter to the Ephesians developed the theme of Christ’s elevation to the highest position in the cosmos for our salvation. In Ephesians 4, Paul discussed Christ’s descent into Hades in light of Christ’s later ascension to heaven.

Now this, ‘He ascended’—what does it mean but that He also first descended into the lower parts of the earth? (Ephesians 4:9; OSB; emphasis added)

In his epistle, the Apostle Peter gave a more detailed explanation of Christ’s descent into Hell in light of the impending Judgment Day.

By whom also He went and preached to the spirits in prison, who formerly were disobedient, when once the Divine longsuffering waited in the days of Noah. (1 Peter 3:19-20; OSB; emphasis added)

For this reason the gospel was preached also to those who are dead, that they might be judged according to men in the flesh, but live according to God in the spirit. (1 Peter 4:6; OSB; emphasis added)

Apparently, in preparation for the Final Judgment everyone, both living and dead, will have some knowledge of the Gospel.

Protestants pride themselves on their biblical exposition, but I had never heard a sermon on these verses or on the theme of Christ’s descent into Hell during my twenty-plus years as a Protestant. The reasons for this oversight is not all that surprising. These verses don’t fit in well with the Protestant dogma sola fide (justification by faith alone) which gives heavy emphasis to the penal atonement model of salvation. Yet what we see here is a strand of biblical teaching that began in the Old Testament, is reiterated by Christ, and expounded by the two preeminent Apostles: Peter and Paul.

Protestant and Evangelical readers might ask: So what are the practical implications of Christ’s descent into hell? Below are some of the practical implications:

- Hell is not an unknown place, for Christ has gone there for us.

- Hell is not a place of complete hopelessness, for Christ has evangelized Hell.

- Hell is not Satan’s domain, for Christ has invaded Hell and taken death captive.

- Hell is not the final destination, for the gates of Hell have been shattered and the captives liberated.

- We need not fear death, for Christ our Captain has gone before us leading the way to heaven.

Resurrection Icon – Death Taken Captive

The Apostles’ Creed

This strand of biblical teaching would later find expression in a line in the Apostles Creed that many Protestants find baffling:

I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord,

who was conceived by the Holy Spirit

and born of the virgin Mary.

He suffered under Pontius Pilate,

was crucified, died, and was buried;

he descended to hell.

The third day he rose again from the dead.

He ascended to heaven

and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty.

From there he will come to judge the living and the dead. (Source)

The Apostles Creed represents an ancient baptismal creed that became part of the liturgical life of western churches. Because the early Christians regularly recited the Apostles Creed, Christ’s descent into Hell was widely known. This stands in contrast to modern day Evangelicalism which is largely ignorant of the Apostles Creed and the theology behind it. My former Protestant home church said the Apostles Creed every few years. That’s how rarely we used it!

The Witness of the Church Fathers

An examination of the Church Fathers shows a widespread acceptance of Christ’s descent into Hell. Irenaeus of Lyons (died c. 200), one of the earliest Church Fathers, in Against Heresies 4.27.2 (ANF Vol. 1 p. 499) paraphrases 1 Peter 3:19-20:

It was for this reason, too, that the Lord descended into the regions beneath the earth, preaching His advent there also, and [declaring] the remission of sins received by those who believe in Him.

Here we see an explicit reference to the Gospel being proclaimed in Hell by none other than the Lord Jesus himself. Hell is no longer a place of hopelessness, but one in which the dead can be saved through faith in Christ.

Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 310-386) in his catechetical lectures taught Christ’s descent into Hell to redeem the righteous.

He was truly laid as Man in a tomb of rock; but rocks were rent asunder by terror because of Him. He went down into the regions beneath the earth, that thence also He might redeem the righteous. (Lecture 4.11; NPNF Vol. 7 p. 22; emphasis added)

He also linked Christ’s descent into Hell to a puzzling verse in Matthew’s Gospel (27:52-53) which spoke of the dead rising and entering into Jerusalem:

I believe that Christ also was raised from the dead; for I have many testimonies of this, both from the Divine Scriptures, and from the operative power even at this day of Him who arose — who descended into hell alone, but ascended thence with a great company; for He went down to death, and many bodies of the saints which slept arose through Him. (Lecture 14.18; NPNF Vol. 7 p. 99; emphasis added)

Hilary of Poitiers (c. 315-368), one of the less well-known Church Fathers, was a staunch defender of Christ’s divinity against the Semi-Arians. In On the Trinity (De Trinitate) Hilary discussed Christ’s descent into Hell in connection with the confession made by the Good Thief:

When He descended to Hades, He was never absent from Paradise (just as He was always in Heaven when He was preaching on earth as the Son of Man), but promised His martyr a home there, and held out to him the transports of perfect happiness.

. . . for the Lord Who was to descend to Hades, was also to dwell in Paradise. Separate, if you can, from His indivisible nature a part which could fear punishment: send the one part of Christ to Hades to suffer pain, the other, you must leave in Paradise to reign . . . . (On the Trinity 10.34; NPNF Vol. 9 p. 190; emphasis added)

The point Hilary is making is that the alleged contradictions that appear to contradict Christ’s divinity can be cleared up by taking into account Christ’s two natures, that is, Christ was at the same time both divine and human in his Incarnation.

Gregory of Nazianzen (330-389) in his Second Oration on Easter (Orations 45.24) declared:

If He descend into Hell, descend with Him. Learn to know the mysteries of Christ there also, what is the providential purpose of the twofold descent, to save all men absolutely by His manifestation, or there too only them that believe. (NPNF Vol. VII p. 432; emphasis added)

Gregory’s phrase “twofold descent” refers to Christ’s descent from heaven to earth, and then from the world of the living to the world of the dead. Christ’s purpose for doing so is for our salvation. The phrase “save all men absolutely” points to a broader understanding of salvation than just the forgiveness of sins.

Ambrose of Milan (c. 339-397) in On the Christian Faith related Christ’s two natures to his descent into Hell:

Distinguish here also the two natures present. The flesh hath need of help, the Godhead hath no need. He is free, then, because the chains of death had no hold upon Him. He was not made prisoner by the powers of darkness, it is He Who exerted power amongst them. (Book 3.4.28; NPNF Vol. 10 p. 246; emphasis added)

Then,

Now, if it please you, let us grant that, in accordance with the mystic prophecy, the substance of Christ was present in the underworld—for truly He did exert His power in the lower world to set free, in the soul which animated His own body, the souls of the dead, to loose the bands of death, to remit sins. (Book 3.14.111; NPNF Vol. 10 p. 258; emphasis added)

Here Ambrose showed how Christology relates to the Christus Victor understanding of salvation. Ambrose is a prominent and influential Latin Father. It was he who brought Augustine to faith in Christ.

Augustine of Hippo (354-430), whose teaching gave rise to the theology of Western Christianity, both Roman Catholic and Protestant, in no uncertain terms affirmed Christ’s descent into Hell. He wrote in Letter 164 Chapter 2:

It is established beyond question that the Lord, after He had been put to death in the flesh, “descended into hell;” for it is impossible to gainsay either that utterance of prophecy, “You will not leave my soul in hell,” — an utterance which Peter himself expounds in the Acts of the Apostles, lest any one should venture to put upon it another interpretation — or the words of the same apostle, in which he affirms that the Lord “loosed the pains of hell, in which it was not possible for Him to be holden.” Who, therefore, except an infidel, will deny that Christ was in hell?

Augustine wrote this letter because even back then there were people who doubted that Christ descended to Hades. His fierce retort against the skeptics of his time, likening them to unbelievers, should give pause to our present-day Protestant skeptics.

John of Damascus (c. 675-c. 749) wrote the closest thing to a systematic theology in the early Church. In his Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (Chapter 29), Saint John devoted one brief chapter to Christ’s descent into Hades.

The soul when it was deified descended into Hades, in order that, just as the Sun of Righteousness rose for those upon the earth, so likewise He might bring light to those who sit under the earth in darkness and shadow of death: in order that just as He brought the message of peace to those upon the earth, and of release to the prisoners, and of sight to the blind , and became to those who believed the Author of everlasting salvation and to those who did not believe a reproach of their unbelief, so He might become the same to those in Hades: That every knee should bow to Him, of things in heaven, and things in earth and things under the earth. And thus after He had freed those who had been bound for ages, straightway He rose again from the dead, showing us the way of resurrection. (NPNF Vol. 9 pp. 72-73; emphasis added)

In this short passage, John of Damascus interweaves several biblical passages around the theme of Christ’s descent into Hades: Malachi 4:2, Isaiah 9:2, 1 Peter 3:19, and Philippians 2:10. Saint John teaches us that Christ took his ministry of miracles and preaching to Hades when he died. We learn that Hell is not exempt from Christ’s ministry of salvation for Jesus Christ is Lord and Savior of all people everywhere, both the living and the dead.

In summary, we find a patristic consensus that ranges from Irenaeus of Lyons in the second century to John of Damascus in the eighth century. Both Greek and Latin Fathers bore witness to this doctrine. Furthermore, we find this doctrine expressed in the worship life of the early Church, e.g., the Apostles Creed, which is still used by Western Christians and in the Holy Saturday services celebrated by the Orthodox. Thus, we can say that the doctrine of Christ’s descent to Hades is a fundamental Christian teaching as it meets the criteria set forth in the Vincentian Canon: “Quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est” (That Faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all). (Commonitory [6])

Calvin’s Break From the Patristic Consensus

John Calvin

It came as a surprise to me to find that John Calvin understood Christ’s descent to Hades metaphorically. In his discussion of the fate of those who died and the place of the dead known as Limbo (Limbus), Calvin regards this to a “fable” and something “childish” taught by “great authors” (the Church Fathers):

Though this fable has the countenance of great authors, and is now also seriously defended by many as truth, it is nothing but a fable. To conclude from it that the souls of the dead are in prison is childish. And what occasion was there that the soul of Christ should go down thither to set them at liberty? (Institutes 2.16.9; Vol. 1 p. 514; emphasis added)

Calvin was of the opinion that the line in the Apostles Creed regarding Christ’s crucifixion, death, and burial referred to Christ’s physical sufferings and the following line about Christ’s descent to Hades referred to Christ’s internal suffering as he experienced divine wrath on behalf of sinful humanity.

But, apart from the Creed, we must seek for a surer exposition of Christ’s descent to hell: and the word of God furnishes us with one not only pious and holy, but replete with excellent consolation. Nothing had been done if Christ had only endured corporeal death. In order to interpose between us and God’s anger, and satisfy his righteous judgment, it was necessary that he should feel the weight of divine vengeance. . . . .

But after explaining what Christ endured in the sight of man, the Creed appropriately adds the invisible and incomprehensible judgment which he endured before God, to teach us that not only was the body of Christ given up as the price of redemption, but that there was a greater and more excellent price—that he bore in his soul the tortures of condemned and ruined man. . . . .

Hence there is nothing strange in its being said that he descended to hell, seeing he endured the death which is inflicted on the wicked by an angry God. (Institutes 2.16.10; Vol. 1 p. 514; emphasis added)

Calvin’s emphasis here is on Christ’s sufferings to appease the wrath of an “angry God.” Here we see in stark terms the penal atonement model of salvation (which assumes a wrathful deity) that many find grossly overplayed, if not deeply repugnant. What I find surprising is how Calvin cavalierly discards the ancient Christus Victor model of salvation and replaces it the penal atonement model. Also upsetting was Calvin’s condescending attitude towards the Church Fathers. To ignore the teaching on Christ’s descent to Hell, Calvin brings a novel, allegorical reading to the Apostles Creed. That Calvin’s reading is a minority position can be seen in the fact that Martin Luther did not jettison the traditional reading of the Apostles Creed. In his 1533 sermon at Torgau, Luther affirmed the traditional understanding that Christ entered Hell as Victor over Satan and his host (Bente). While Luther introduced a new soteriology (doctrine of salvation) with his novel understanding of justification (sola fide), Calvin made even bigger break with a soteriology based on the penal atonement model, which would grow to largely ignore, if not exclude the ancient patristic models of salvation used by the Church Fathers for centuries

Pastor John Piper

Calvin’s dismissive attitude towards the doctrine of Christ’s descent into Hell would have long term consequences. It would lead to the descensus controversies that would roil sixteenth century Protestantism (Bagchi p. 198). Calvin’s innovative understanding was accepted within Reformed circles, but when brought into contact with other Protestant traditions it traditions it came across as bizarre. Nonetheless, Calvin’s view became part of the Reformed tradition. It can be found in Question 44 of the Heidelberg Catechism. Reformers like Theodore Beza would, on their own imitative, omit that line (Bagchi p. 199). Even today, prominent Reformed theologians like John Piper have taken the liberty to omit that line. They “retain” aspects of ancient Christianity and throw out what they don’t like. This is like wanting to have one’s cake and eat it too.

When I studied church history at seminary, I learned that Protestantism’s heavy emphasis on the penal aspects of Christ’s dying on the Cross is a relatively recent doctrine that emerged to prominence in the 1500s. What we see in the Apostles Creed reflects the theology of the early Church which reflected the patristic doctrine of Christus Victor. The fact that many Protestants today are unfamiliar with Christ’s descent in Hades and even the Apostles Creed show how far Protestantism has drifted from its ancient Christian roots. This is not to say that Protestants and Evangelicals should relinquish the penal model of salvation altogether, but that they should incorporate the ancient patristic model of Christus Victor into their theology. A good resource for this is Gustav Aulen’s theological classic Christus Victor. Protestantism has paid a heavy price in forsaking its roots in the early Church. It has adopted a novel soteriology accompanied by a new form of worship resulting in their estrangement from Ancient Christianity.

Two Paradigms of Salvation

When I was a Protestant it was hard to fit the verses about Christ’s descent to Hell into the penal substitutionary theory of salvation. In this model, all that mattered was Christ’s suffering and dying on the Cross. His death was the crucial element; everything else was superfluous. This led to strained attempts to explain how Christ’s resurrection was necessary for our salvation. More prominent in the early Church was the recapitulation theory in which Christ as the Second Adam retraced human existence from birth to death, from conception in his mother’s womb to his descent into the underworld. The underworld was where all the dead souls—good and bad—awaited the Final Judgment. Like the other humans who died, Christ descended into Hades. However unlike other humans, this was the uncorrupted Second Adam who was unjustly sentenced to death, Immanuel who is “God With Us.” John Chrysostom in his famous Easter sermon declared:

It [Hell] took a body [Jesus Christ], and, lo, it discovered God.

It took earth and behold! it encountered Heaven.

It took what it saw, and was overcome by what it could not see.

O death where is your sting? O Hades [Hell], where is your victory?

Christ is risen, and you [Hell] are annihilated.

Christ is risen and the demons have fallen.

Christ is risen and the Angels rejoice.

Christ is risen and life is liberated.

Christ is risen, and the tomb is emptied of the dead. . . .

Where Protestantism puts the emphasis on the forgiveness of sins obtained through Christ’s death on the Cross, Orthodoxy puts the emphasis on the defeat of sin, death, and the devil through Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. What saves us is not an event but rather a Person, Jesus Christ. This is not to say that Protestantism’s doctrine of salvation is all wrong. However, Protestantism’s reductionism unduly emphasizes only one part of a far richer and fuller picture of Salvation in Christ. Orthodoxy’s holistic understanding of salvation is multifaceted. It teaches us about the many ways Christ saves us: freeing us from captivity to Satan and the demons, the healing our souls and body, bringing us back home and restoring us to our standing as God’s beloved children, making us wise, transforming us into his likeness and more. Unlike Protestantism’s novel approach to salvation, Orthodoxy preserves the teachings of the early Church to the present day.

This year [2018], Orthodox Easter will come one week after Western Easter. This will give Protestants and Evangelicals an opportunity to compare their celebration of Easter with Orthodoxy’s ancient liturgy. It may come as a surprise that on Saturday there are two services. On Saturday morning, the Orthodox Church celebrates Christ’s harrowing of Hell. The mood of this service is that of a quiet joy in anticipation of the Easter service. We invite our Protestant friends to come to the Saturday morning service and celebrate with us Christ’s descent into Hades to set the captives free. Then Saturday midnight, the Liturgy is celebrated with exuberance and extravagance. Over and over, we cry out: Christ is Risen! This service is the high point of Orthodox worship. Tip: Check ahead for the specifics of the service. Better yet, ask an Orthodox friend to take you along.

Come and see!

Robert Arakaki

Additional Readings

Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev. 2002. “Christ the Conqueror of Hell” (lecture)

Gustav Aulen. 1931. Christus Victor: A Study of the Three Main Types of the Idea of Atonement

David V.N. Bagchi. 2008. “Luther Versus Luther? The Problem of Christ’s Descent into Hell in the Long Sixteenth Century.” Perichoresis 6.2.

F. Bente. “XIX. Controversy on Christ’s Descent into Hell.” The Book of Concord

Robert B. Kruschwitz. 2014. “He Descended into Hell.” Christian Reflection – A Series in Faith and Ethics

Scot McKnight. 2018. “Holy Saturday – What Happened on Saturday to Jesus?” Jesus Creed

John Piper. 2008. “Did Christ Ever Descend to Hell?” DesiringGod.org

Recent Comments