An Orthodox Response to Spencer Boersma’s “The Impotence of Calvinism?” (2 of 2) (1 of 2)

This week’s posting is a continuation of my response to Spencer Boersma’s “The Impotence of Calvinism.” In this posting I will be looking at how an Orthodox priest might approach Young Man’s problem differently.

The plight of Boersma’s Reformed pastor is that his tool box is a limited one. An Orthodox priest has a much fuller array of tools available to him.

The Divine Liturgy

Consistent attendance at weekly Sunday Service is foundational for Orthodox spirituality. The Liturgy provides focus and power to our individual spirituality. It shapes our hearts and minds as we participate in the prayers and hymns. It is not just a nice Sunday service. For the Orthodox it begins with the Vespers service at Saturday sundown followed by Matins and the Liturgy on Sunday morning. Standing throughout the Liturgy, singing the hymns, paying attention to the prayers, and keeping the pre-Communion fast (no food or drink after midnight) comprise a regime of spiritual disciplines far more demanding than many Protestant services today. Liturgical worship is radically different from the feel good spiritual high of mega churches or the lengthy sermon centered services of traditional Protestantism.

I like to think of the Liturgy as a spiritual nuclear reactor; if one stands in the radiation field one gets irradiated or energized by the Divine Presence. There are two key moments in the Liturgy: the reading of the Gospels in which we hear the words of Christ, and the Eucharist in which we feed on the Body and Blood of Christ. The Eucharist in the early Church was not viewed as symbolic reminders but as “the medicine of immortality.” In the pre-Communion prayer by John Chrysostom we read:

Seeing the divine blood, have fear, O man, for it is coal that burns the unworthy. It is God’s body that deifies and nourishes me; it deifies the spirit and nourishes the mind mystically.

Loving Master, Lord Jesus Christ, my God, do not let these Holy Things be to my condemnation because of my unworthiness, but rather for purification and sanctification of my soul and body, and as a pledge of the life and kingdom to come. For it is good for me to cleave to God, and to place the hope of my salvation in the Lord.

This understanding of the real presence in the Eucharist is radically different from what many Protestants are accustomed to, even for the Reformed Christians who affirm the real presence in the Lord’s Supper.

Confession

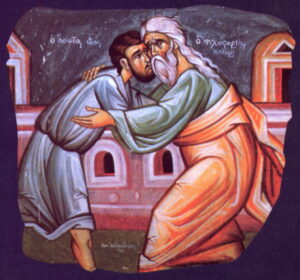

This is probably the most potent tool that the Orthodox priest has that the Reformed pastor does not have. If the Young Man were to ask: “Father, why did I sin?” The priest can reply: “Let us go before God in prayer and we will deal with your sin problem in the sacrament of confession.” In the Orthodox approach to confession one usually stands or kneels before the icon of Christ with the priest standing at one’s side. To use Evangelical language the Orthodox priest and the penitent go in prayer to the foot of the Cross, and there the penitent confesses his sins to Jesus Christ directly. The priest is a bystander acting as a witness. In the sacrament of confession the priest prays:

O God our Saviour, who by thy Prophet Nathan didst grant unto repentant David pardon of his transgressions, and didst accept Manasses’ prayer of penitence: Do thou, with thy wonted love towards mankind, accept also thy servant, N., who repenteth him (her of the sins which he (she) hath done, pardoning his (her) offences, and passing by his (her) iniquities. For thou hast said, O Lord: With desire have I desired not the death of a sinner, but rather that he should turn from the wickedness which he hath committed, and live; and that even unto seventy times seven, sins ought to be forgiven.

By speaking out loud the sin, the penitent is bringing the sin out from the shadows of shame and secrecy into the light of humility and faith. Confession is also an opportunity for healing and coaching. Oftentimes the priest will give the penitent Christian advice about how to strengthen their spiritual life and live a life pleasing to God. Going to confession is often an uncomfortable experience because it involves baring one’s soul to the priest. This is similar to the discomfort one feels when one undergoes a physical examination by the physician. Frederica Mathewes-Green in At the Corner of East and Now (p. 65) wrote:

Preparing to go to confession can be stressful; one feels awkward and embarrassed to say some things aloud. But saying them, and then hearing them forgiven, turns out to be surprisingly liberating. It’s freeing to have no secrets and to know that one’s most shameful moments are seen, known, and forgiven by God. Receiving this forgiveness through the priest, hearing the words aloud, contributes to a sense of permanency and reliability; its’ not just you talking to the bedroom ceiling. As my husband says, on the way in people say, “I hate confession!” On the way out they say, “I love confessions!“

The Orthodox understanding is that when we come to faith in Christ and are born anew in the sacrament of Baptism all our sins have been forgiven. In baptism all our previous sins have been forgiven but not future sins. Because they have not yet happened these sins are hypothetical. But when they become real then they need to be dealt with through repentance and confession.

Fasting

The Weekly Fasts. All Orthodox Christians are expected to keep the Wednesday and Friday fasts. The weekly fasts consists primarily of abstaining from meat, fish, and dairy products. This is an ancient spiritual discipline which dates back to the early church. According to the first century Christian document, Didache 8:1, the Christian fasts are a continuation of the Jewish biweekly fasts. This makes for spiritual discipline as a corporate endeavor, something the Church does together than an individual affair.

Fasting has for the most part been discarded by Protestants. They shy away from fasting out of fear of works righteousness or if they do endorse fasting, they stress that you do it on your time in your own way. But for the Orthodox fasting is a way of denying the desires of the flesh and of submitting to Christ. It is also a way of strengthening our souls. For many Christians our inner life is in disarray like an exhausted mom whose house is taken over by unruly children, or like the owner of a dog who is pulled along by the dog instead being the master. Oftentimes a priest will prescribe a fasting regime for persistent sins. By learning to control the desires of our stomachs we learn to control the other desires (passions) becoming rational beings no longer swayed by our feelings and wants.

Fasting is a powerful tool for dealing with situations where demonic influences are involved (see Mark 9:29 NKJV). Pope Leo the Great, a fifth century church father, wrote:

Therefore abstaining from food and drink, they [the Jews] applied the discipline of strict correction to themselves, and in order to conquer their foes, first conquered the allurements of the palate in themselves. And thus it came about that their fierce enemies and cruel taskmasters yielded to them when fasting, whom they had held in subjection when full. And so we [the Christians] too, dearly beloved, who are set in the midst of many oppositions and conflicts, may be cured by a little carefulness, if only we will use the same means [fasting]. For our case is almost the same as theirs, seeing that, as they were attacked by foes in the flesh so are we chiefly by spiritual enemies. (“Sermon XXXIX.I On Lent” Sermons of Leo the Great. NPNF Second Series Vol. XII p. 152)

Relying, therefore, dearly-beloved, on these arms, let us enter actively and fearlessly on the contest set before us; so that in this fasting struggle we may not rest satisfied with only this end, that we should think abstinence from food alone desirable. For it is not enough that the substance of our flesh should be reduced, if the strength of the soul be not also developed. (“Sermon XXXIX.V On Lent” Sermons of Leo the Great. NPNF Second Series Vol. XII p. 153)

Abstaining from food makes little sense in a religious tradition like Calvinism that puts the emphasis on the intellect, but fits in well with a religious tradition like Orthodoxy that has a more holistic view of the human person. I would urge my Calvinist friends to give thought to the mind-body separation that seems to pervade their worldview. This theological outlook is at odds with the more integrated and holistic spirituality of the early Christians.

Great Lent. For me the transition from popular Evangelicalism to Orthodoxy was a lot like a couch potato joining a family of athletes. If the twice a week fasts are like a routine morning jog, Orthodoxy’s 40 days of fasting in Orthodoxy is like the Boston Marathon or the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon.

Great Lent is a time of fasting, prayer, and almsgiving. In addition to the fasting are the midweek church services. It can be a tremendous challenge for many but they end up spiritually stronger. Under the spiritual regimen of Calvinism, the Young Man would become more developed intellectually but remain undeveloped in other areas of his life. Under the holistic approach of Orthodox Great Lent the Young Man will be challenged not only in his intellect, but also in his heart and his relationship with the Church and with those in need outside the Church.

Prayer. Personal devotions are valued in both the Protestant and Orthodox traditions. In contrast to Protestantism’s emphasis on extemporaneous prayer, Orthodoxy values liturgical prayers. It also values prayers composed by the saints. The value of using these prayers are much like a beginning pianist imitating the great composers. Orthodoxy also has available for its members prayer books that contain the Morning Prayer and the Evening Prayer, and prayers for other occasions. One of the more popular prayer book is the tiny pocket prayer book sponsored by the Antiochian Archdiocese. In addition there are: A Manual of Eastern Orthodox Prayer and My Orthodox Prayer Book. For those interested in the Slavic tradition, there are the Orthodox Prayer Book (Jordanville) and the Old Orthodox Prayer Book (Russian Old Believer).

Probably the most characteristic example of Orthodox spirituality is the black knotted prayer rope and the Jesus Prayer. Orthodox Christians will say: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me” at each knot. The constant saying of the Jesus Prayer will etch the prayer onto our hearts and mind reshaping our inner man.

Monasticism. If the Orthodox parish priest is like the family doctor, the monastery is like the Mayo Clinic of Orthodox spirituality. Orthodox monastics devote their lives to prayer much like the way pro football players devote their lives to athletic excellence. Thus, if an Orthodox priest finds himself with a difficult pastoral challenge he has the option of recommending the Young Man do a pilgrimage to a monastery. Many Orthodox Christians go to a nearby monastery for a personal retreat and for spiritual direction. Contemporary accounts of pilgrimages to Orthodox monasteries can be found in Touching Heaven: Discovering Orthodox Spirituality on the Island of Valaam (2003), The Mountain of Silence: A Search for Orthodox Spirituality (2002), and The Scent of Holiness: Lessons From a Women’s Monastery (2012).

The Calvinist pastor on the other hand pretty much operates like an independent physician who has no nearby hospital to rely on. Thus many Reformed pastors, if they ever run into especially difficult pastoral cases, are pretty much on their own. They might be able to consult with fellow pastors or with their seminary professors but that is about it.

In our modern and post-modern culture saturated material excess and framed by materialistic worldview, we have largely lost the place and importance of the monastery and monastic life for Christian spirituality. This neglect is evident even in many Orthodox parishes. Yet in many Protestant settings the subject of monasticism and the monastic lifestyle is subject to scorn and ridicule. Instead of visiting monasteries, many Protestants attend conferences or go on cruises where they hear inspiring talks. This situation is tragic. We need to awaken to the widespread spiritual poverty in our midst to recognize the important role monasteries play in supporting the spiritual vigor of the larger Church.

Lives of the Saints. In every Sunday service the Orthodox Church commemorates saints of the day. During the Matins service which precedes the Divine Liturgy excerpts from the lives of the saints are read. These are in part a lesson in church history but are also a celebration of the Holy Spirit’s work in a person’s life. One of the more conspicuous examples of this is the story of Saint Mary of Egypt whose life story is recounted on the fifth Sunday of Lent. Athanasius the Great Life of St. Anthony is an early classic about a great desert father. The Prologue of Ohrid is a multi-volume series of the lives of Orthodox saints.

Protestantism’s neglect of the lives of the saint is partly due to its rugged individualistic mindset. We will live the Christian life our own way: “No one tells me what to do!” Our fear of “ancestor worship” has resulted in a huge gap in church history among Protestants. Instead of being rooted in history, many Protestants today are enamored with their favorite modern theologians or radio preachers but are woefully ignorant of their rich Christian heritage. When I need examples for combating the passions of the flesh I reflect on John the Baptist and Saint Mary of Egypt. I can also find spiritual wisdom in the great spiritual classic The Ladder of Divine Ascent by Saint John of the Ladder. Many people also find great value in the Philokalia, a compilation of texts by spiritual masters from 300 to 1400. The wisdom of these books become even more useful if used in conjunction with the guidance of a wise father confessor (spiritual director).

Summary

The predicament of Boersma’s Young Man is common across Christian traditions. However, theological paradigms greatly influence the responses the pastor or priest will make. Boersma’s hypothetical dialogue illustrates some of the limitations and constraints of Reformed theology. Orthodoxy on the other hand does not agonize whether one is part of the elect. Instead it takes a more direct and practical approach to the problem of living a holy life. Orthodoxy is full of ancient wisdom expressed in song and teachings, historical examples of courage and humility, a framework for worship. Orthodoxy draws on Holy Tradition and a host of spiritual tools and disciplines handed down to us from the early Church. What I have tried to do is show how Orthodoxy provides a more holistic and effective course of treatment for problem of sin. For those spiritually wounded and struggling to live holy lives the Orthodox Church says: Come and see! Come to the spiritual hospital for the healing of your souls.

Recent Comments