A reader wrote the following:

Dear Sir,

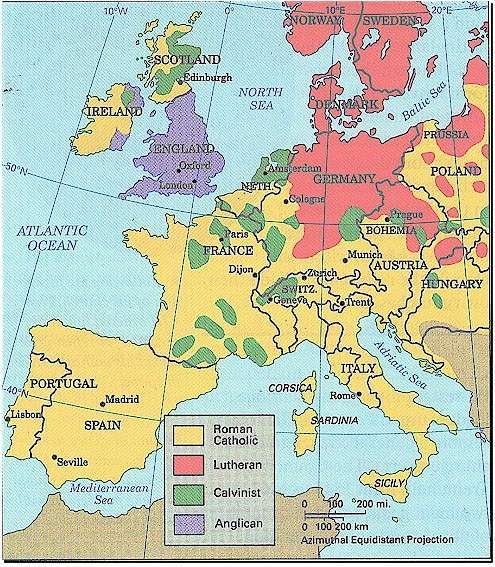

I really appreciate this article. I come from a Reformed background. I am one who laments that Protestantism has made so many sects. Yet, I want to ask a very simple question and its not out of spite, I am really curious to know more about how Eastern Orthodoxy holds things together theologically, what happens when the Church Fathers conflict with the Scriptures? The Fathers themselves had different ideas and were not all of the same mind on every issue. The Roman Catholic Church has its Magisterium. The trouble with their position is that they claim their teaching does not err. As much as I have sympathy for your position related to the severe weaknesses of Protestantism in regard of creating sects (which didn’t have to happen), as a Protestant Sola Scriptura seems to be a necessary conclusion even if it is messy.

Ethan

My Response

Thank you for your blunt questions and your willingness to engage us here! I have broken down your questions into three points with my response following.

1) How does Orthodoxy holds things together theologically?

What unites Orthodoxy is Apostolic Tradition. Apostolic Tradition consists of written Tradition (Scripture) and unwritten Tradition (the oral teachings and praxis of the Apostles) (2 Thessalonians 2:15; 2 Timothy 1:13-14). Unlike Protestantism which insists on the “Bible alone” (sola scriptura), Orthodoxy teaches that Scripture is to be understood within the context of the Church, primarily in the matrix of its Liturgy, the Church Fathers, and the Ecumenical Councils.

Fractio Panis — 3rd century Roman catacomb painting

One good example of how oral Tradition complements written Tradition can be seen in the Eucharist. All early Christian worship services had the Eucharist and all early Christians believed in the real presence — that Christ’s body and blood are truly present in the Eucharist. This was an implicit understanding shared by the early Christians. According to Ignatius of Antioch (d. 107) it was the Gnostic heretics who denied the real presence in the Eucharist viewing it as symbolic (Letter to the Smyrnaeans 7.1).

Zwingli vs. Luther at the Marburg Colloquy – 1529

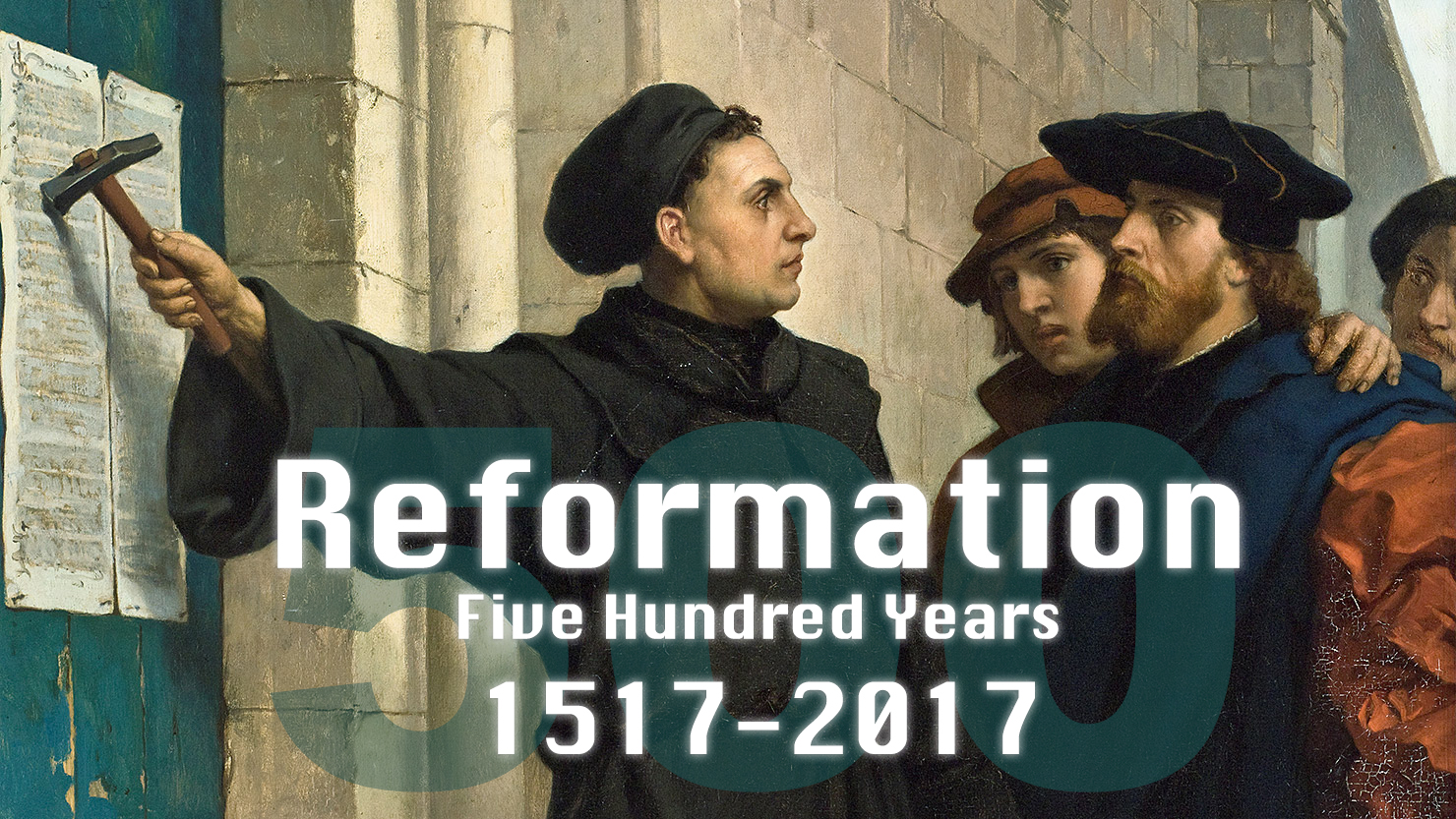

This belief in the real presence was transformed into a precise formula in the West during the Middle Ages resulting in the distinctive Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. In the East, the Orthodox position was that the real presence was a mystery. When the Protestant Reformers sought to reform Christian worship on the basis of sola scriptura, they ran into the problem of how to interpret Jesus’ words: “This is my body.” Were the words to be understood literally or symbolically? Not having oral Tradition to fall back on, Luther and Zwingli reached an impasse and parted ways. One has to wonder whether sola scriptura was the underlying cause of Protestantism’s earliest church split. One also has to wonder whether sola scriptura is the reason why Protestantism never had a shared common worship.

Oral Tradition can also be seen in the understanding that Christian worship was to take place on Sunday, was to have the Eucharist, and follow a liturgical order (see Justin Martyr’s First Apology 65-67). There is no explicit Scripture passage that mandates a liturgy with the Eucharist every Sunday. These are all part of oral Tradition that emerged alongside the Bible. It is important to keep in mind that the biblical canon and the Liturgy emerged simultaneously within the early Church, both are the result of the Church being led by the Holy Spirit. Thus, oral Tradition plays an important part in the unity of the Faith as Scripture.

All Orthodox parishes today follow the same Liturgy. The Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom provides a rich hermeneutical context for understanding the Bible. I strongly recommend you attend the Liturgy for several Sundays—at least 6 to 8—taking note of Scripture being expressed in the prayers and hymns in the Liturgy. The Liturgy is beautifully complex, multi-layered and multi-sensory, involving whole person, body and soul with the goal of drawing the worshiper closer to God.

The Liturgy with the church calendar provides another commonality among Orthodox parishes across the world today as well as providing a historical link to the early Church. This calendar is not a piece of paper hanging on the wall, but rather a schedule of services, prayers, and hymns to be used on designated days. Through the feast day services Orthodox parishes around the world remember the lives of the saints and important historical events. When I was a Protestant I learned church history through reading books but as an Orthodox Christian I learn church history through attending services. In Protestantism, church history tends to be specialized knowledge, not shared knowledge as in Orthodoxy. This shared understanding of church history and the saints is another factor to Orthodox unity. Without knowledge of family history, we become susceptible to becoming isolated individuals intent on developing our own identities.

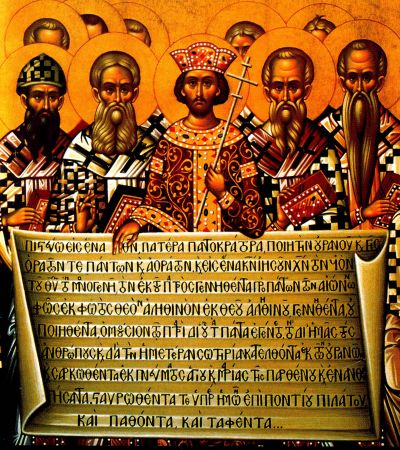

Another source of unity is Orthodoxy’s adherence to the Seven Ecumenical Councils. At these Councils major heresies were refuted by the Church Catholic. There have been other later councils that while not considered Ecumenical have been universally received by Orthodox churches, for example, the 1623 Council of Jerusalem which rejected Calvinism. Another unifying factor is the Nicene Creed which we recite every Sunday. The Nicene Creed, while it does not define every point of theology, nonetheless provides the parameters of what all Christians are obliged to believe. When Orthodox Christians recite the Nicene Creed we are affirming the teaching authority (magisterium) of the Ecumenical Councils, especially the first two. Orthodoxy’s objection to the unilateral insertion of the Filioque is indicative of Orthodoxy’s adherence to the conciliar approach to doing theology. The conciliar approach underlying the Nicene Creed is radically at odds with the Protestant theological method which is based on sola scriptura.

Then there is the episcopacy which consists of a living, historical chain of bishops who trace their spiritual lineage back to the original Apostles. The bishop as the recipient and guardian of Apostolic Tradition also oversees the local liturgical celebrations. No priest can validly celebrate the Eucharist apart from the bishop’s authorization (Ignatius of Antioch’s Letter to the Smyrnaeans 8). Keep in mind that this authority is a covenantal authority. When Christ said: “This is the blood of the New Covenant,” he was implying that Christianity would be a covenant community with a covenant-based leadership. In many ways the authority of the Orthodox Church traces back to the Last Supper, whereas Protestantism’s authority traces to the Reformers in the 1500s taking the Bible as their starting point for their theologizing. However, the problem with the Protestant approach is that the Reformers took into their hands a covenant document (the Bible) without a validly conferred covenant authority to interpret it. Protestants lack this covenant authority because they rejected the historic episcopacy. Lacking the historic episcopacy, the magisterium (teaching authority) in Protestantism shifted to either the university which in the nineteenth century became captive to the European Enlightenment Project or to untethered religious entrepreneurs beholden to nobody except themselves. Theological fragmentation and denominational disarray were the inevitable consequences. This is a sign of Protestantism’s lack of covenantal basis. Because Protestantism rejects apostolic succession, it lacks not only covenantal authority to interpret Scripture but also covenantal unity essential to being part of the one holy catholic and apostolic Church confessed in the Nicene Creed. The local bishop through right teaching and right worship ensures the Orthodox Church’s covenantal unity.

2) What happens when the Church Fathers conflict with the Scriptures?

The first thing to note is that just because a Christian thinker lived long ago does not make him a Church Father. Only a select group of men recognized for their teachings and their holy lives have been honored by the Orthodox Church as “Church Fathers.” This recognition is expressed principally through the church calendar in a feast day honoring their service to Christ. There are some early Christians who had brilliant minds but were not regarded as Church Fathers, for example, Tertullian and Origen.

When you say “conflict with the Scriptures” you would need to be more specific. It might be you are thinking of some early Christians who held eccentric views. Or it might be that you, as a Reformed Protestant, might be siding with the minority viewpoint. For example, if you believe that Scriptures affirm the iconoclast position, then you are favoring the minority position. It might also be that you have not critically considered the problematic aspects of the iconoclast position. When I was a Protestant, I assumed that the icon was the weakest point of Orthodoxy until I took a fresh look at Scripture and read carefully the early Christians’ defense of icons. See my article: “The Biblical Basis for Icons” in which I found that icons do not necessarily conflict with Scripture. In any event, it is a matter of record that the pro-icon position was ratified at the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II 787) and iconoclasm was condemned as heretical. Also, you need to consider that iconoclasm is not universal across Protestantism and that it represents only an extreme end of the Protestant spectrum. Where Orthodoxy is united on the issue of icons, Protestantism is not.

3) The Church Fathers themselves “had different ideas and were not all of the same mind on every issue.”

Your observation is quite accurate that there was quite a bit of diversity among the Church Fathers. Nonetheless, what they had in common was striking when compared to Protestantism. Early Christian theology was essentially liturgical theology. It was not so much written down on paper as it was sung out loud during the Liturgy. The early Church viewed the Eucharist as the central feature of Sunday worship and all affirm the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist. Another common element was the understanding that Christianity was based on oral Tradition received from the Apostles and safeguarded by the bishops. The episcopacy was the norm in early Christianity. Protestant forms of church government like congregationalism and presbyterianism were not the norm. Among the early Christians there was some disagreement as to how to reconcile Jesus being the Son of God with Jewish monotheism. This question became a major crisis with the emergence of the Arian heresy. This heresy was refuted at the Council of Nicea (325). It was for his articulate defense of Jesus’ divinity that Athanasius was recognized as a Church Father. Cyril of Alexandria would be recognized as a Church Father for his defense of Mary as the Theotokos (God-Bearer). It was at the Fifth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople II, 553) that Nestorianism was condemned as heretical and recognition of Mary as Theotokos be made part of the Liturgy. The iconoclast controversy was precipitated by Emperor Leo III’s edict against icons. For his defense of icons John of Damascus would be recognized as a Church Father. It was at the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II, 787) that iconoclasm would be formally condemned as heretical. The early Church encountered numerous heresies and dealt with them through councils–local, regional, and ecumenical—with the assistance of bishops who would later be recognized as Church Fathers. It is not as if conflicts emerged the Church Fathers and were resolved at Ecumenical Councils; but rather heresies surfaced and the bishops came together to deal with these heresies and in the process certain men who played a key role in the upholding of the Apostolic Faith would come to be recognized as a “Church Father” just as an “ordinary” Christian who suffered martyrdom would be recognized as a capital “s” Saint.

Another important aspect of Orthodox unity is the patristic consensus. This “consensus of the Fathers” is usually a reference to the bishops of the Church speaking collectively via an Ecumenical Council. Just as the Holy Spirit guided the Jerusalem Council so likewise he guided later Councils into the truth (cf. Acts 15:28; John 16:13). Please keep in mind that while there have been many church councils, only a few have been recognized as “Ecumenical Councils.” Individually the Church Fathers may err but collectively they bear witness to the Apostolic Faith. Orthodox theology does not seek to neatly and systematically answer every theological question possible in a comprehensive manner similar to the Westminster Confession. of Faith While we remain steadfast on matters of dogma like the Trinity and Christology, there is diversity in other matters like soteriology and eschatology. As an Evangelical in a liberal mainline denomination it distressed me to see pastors and theologians calling into question the dogmas of Christology and the Trinity, and fundamental assumptions of human nature, the Fall, and our salvation in Christ. Since becoming Orthodox, it is a tremendous relief to find myself on the same page on the core dogmas of the Faith as the Orthodox priests I meet. I did not have that certainty when I was Protestant. Whenever I met a UCC minister for the first time, I first needed to feel out their theological orientation: Was he or she a Liberal, an Evangelical, or a liberal Evangelical? The parameter of Orthodox’s Holy Tradition gave me a safe harbor and a sense of integrity that I felt was missing during my time as a Protestant.

What I appreciate about Orthodoxy is how the Church Fathers are very much among us today. The Church Fathers influence how we understand our Faith. When I make reference to Church Fathers like Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great, Basil the Great, or John Chrysostom, Orthodox Christians understand who I’m referring to. The Church Fathers are not remote figures in the past but our companions of faith. Recently my priest concluded his sermon with quotes from two Church Fathers and then closed with ”Holy John Chrysostom pray for us! Holy Basil pray for us!” For my priest Father Alexander, the Church Fathers are part of great cloud of witnesses who surround us right now.

Orthodox Liturgy in Overland Park, Kansas – YouTube video

Closing Thought

I’ll leave you with this thought. In comparison to meticulous neatness of the Reformed confessions, Orthodox theology is messy and at times fuzzy. However, when it comes to the fundamental core dogmas and worship practices of historic Christianity, Orthodoxy is coherent and stable, while Protestantism is becoming increasingly theologically incoherent, liturgically anarchic, and bereft of historical memory. I suspect that you have had little direct experience with real, live Orthodoxy. I would urge you to spend time getting to know living Orthodox Church and come back again for further engagement. In other words, let keep talking to each other!

Robert Arakaki

An Orthodox Assessment

An Orthodox Assessment

Recent Comments