Continuing the Conversation

Pastor John Carpenter recently published a lengthy article on the Gospel Coalition’s website “Answering Eastern Orthodox Apologetics regarding Icons.” The article is in part a response to my earlier article: “A Response to John B. Carpenter’s ‘Icons and the Eastern Orthodox Claim to Continuity with the Early Church.’” One could say that my article and Pastor Carpenter’s two articles represent an ongoing friendly Reformed-Orthodox dialogue, which we welcome. This article will be an assessment and response to his latest article.

Assessment

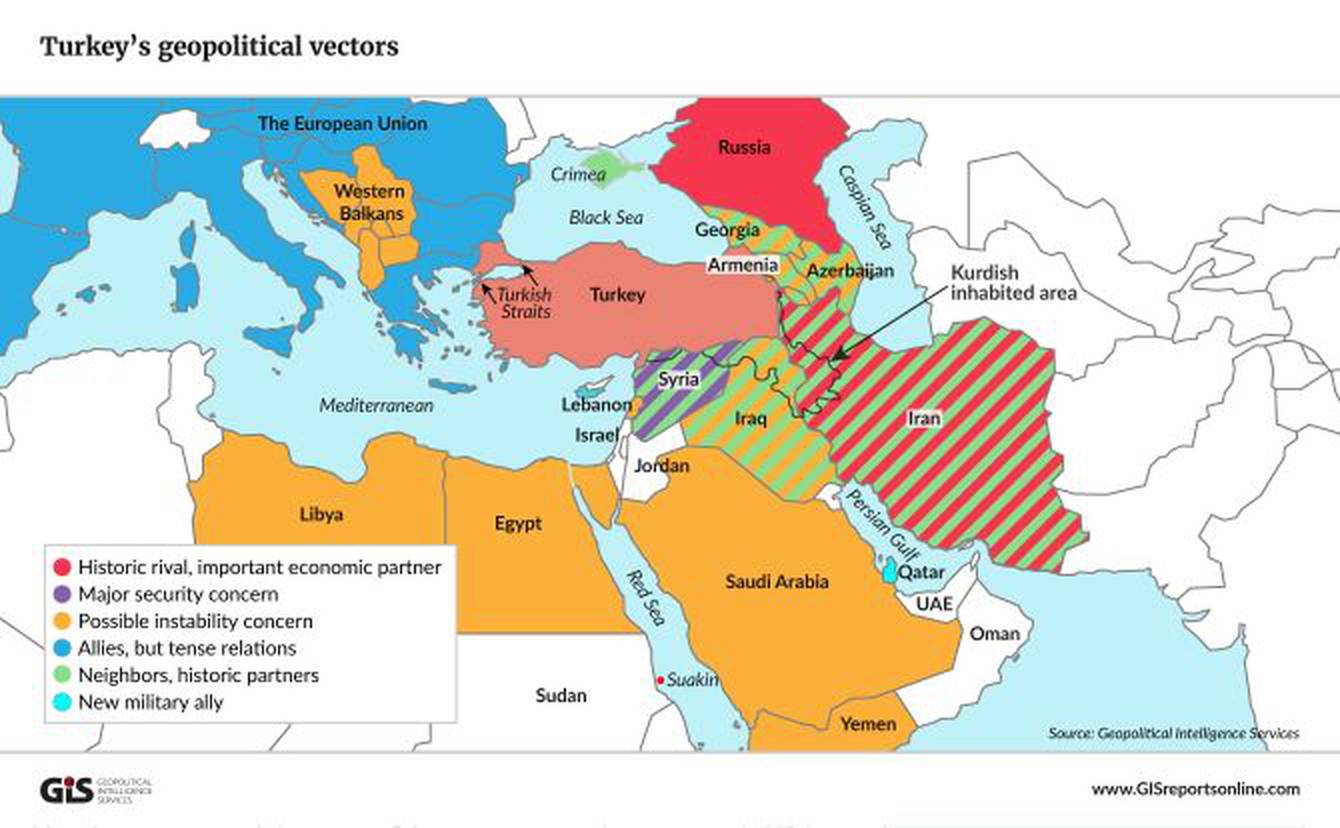

One common weakness in Reformed critiques of Orthodox icons has been either a superficial understanding of icons or reliance on caricatures of the Orthodox understanding of icons. As far as Reformed apologia engaging Orthodoxy goes, this article is one of the better ones. Pastor Carpenter appears to have done some homework as evidenced by the eighty-plus endnotes and his engaging a wide range of well respected Orthodox writers such as Steven Bigham and Gabe Martini. Carpenter’s scholarship is also evidenced by his willingness to cite secular sources such as Milette Gaifman’s 2017 article: “Aniconism: definitions, examples and comparative perspectives.” Despite some very real weaknesses, the quality of Carpenter’s latest article is such that it has helped refine this author’s pro-icon apologia.

In his article Pastor Carpenter approaches icons not just as religious images, but in the way they are used in worship. He concludes the introductory section with a sparse definition of an icon being “a sacred image used in religious devotion.” This focus on the function of icons plays a key role in Carpenter’s latest rebuttal of Orthodox pro-icon apologia. Orthodoxy has historically seen an inextricable connection between what an icon is with what an icon does – it sacramentally mediates the personal presence of Christ and the saints. So John Carpenter’s shift in focus is far from a minor tactical change in Reformed iconoclastic apologia, but one that must be taken seriously.

However, I found his understanding of “iconography” as the use of icons in worship rather eccentric. Conventional definitions of “iconography” focus on the images themselves, not the act of venerating the images in the context of worship as Carpenter would have it. The Cambridge Dictionary defines “iconography” as:

the use of images and symbols to represent ideas, or the particular images and symbols used in this way by a religious or political group, etc.

The Encyclopedia Britannica defined “iconography” as:

. . . the science of identification, description, classification, and interpretation of symbols, themes, and subject matter in the visual arts.

What Rev. Carpenter calls “iconography” would be more appropriately referred to as “icon veneration.”

One more terminological peculiarity of Carpenter’s article is his defining “iconoclasm” as the active destruction of images.

When this prohibition is enforced by the actual destruction of images, aniconism becomes iconoclasm. (§1)

The more widely accepted understanding of “iconoclasm” is either the rejection of religious images or their destruction. The Oxford Dictionary defines “iconoclasm”:

The rejection or destruction of religious images as heretical; the doctrine of iconoclasts.

This is important to keep in mind because it allows John Carpenter to disavow that he is an iconoclast in the general sense of the word by his insisting in his article that “iconoclasm” refers to just the active destruction of religious images and that his position is closer to rigorous aniconism. In this article I will be using the word “iconoclasm” in the more generally accepted sense.

A False Binary?

John Carpenter criticizes Orthodox pro-icon apologia for the “binary” nature of their arguments.

If EOAs [Eastern Orthodox Apologists] can frame the debate as a binary choice between radically rigorous aniconism or full-blown iconography [icon veneration], many people will succumb to the logic of iconography. Hence, they typically argue, “Icons are like family photos. Just like a deployed soldier may kiss a photo of his wife, we kiss icons of Saints who have fallen asleep in Christ.” This is, of course, a false dilemma. (Carpenter 2018; §1)

Carpenter counters Orthodox pro-icon apologia with the concept of aniconism. He argues that the presence of images in the Old Testament Tabernacle as well as in early Jewish and Christian places of worship are consistent with aniconism and do not necessarily indicate that these images were used for worship. To bolster his argument, Carpenter draws on Milette Gaifman’s comparative analysis of the use of images across various religious traditions. Drawing on Gaifman’s article, Carpenter writes:

So the discovery of decorations in catacombs or the synagogue and church of Dura Europos does not necessarily suggest iconography [icon veneration]. One can still be “aniconic” (opposed to icons) and allow decorations. Aniconism is the belief that images should not be used in worship; it is opposition to icons but not necessarily to all images. There is a spectrum of aniconism. Rigorous aniconism insists that the natural or supernatural world should not be represented in any visible way. . . . . When this prohibition is enforced by the actual destruction of images, aniconism becomes iconoclasm. (Carpenter 2018; emphasis added)

Aniconism, then, covers a range from rigorous aniconism in which all images are forbidden, including secular art, in any contexts, whether secular or religious, to mediating views of some images being acceptable in non-religious contexts; to the laxest form of aniconism, that images of all kinds are acceptable, even as decorations in places of worship but not used in worship. It is the prohibition on using an image in acts of devotion that is the sine qua non of aniconism. (Carpenter 2018; §1; emphasis added)

The concept of aniconism has the advantage of allowing us to come to grips with the complexity of the relationship between art and worship in early Christianity. The spectrum of moderate to rigorous aniconism gives us a more flexible framework for assessing so-called early Christian iconoclasm, e.g., Epiphanius, Clement of Alexandria, as well as archaeological evidence of images in early Christian places of worship. While there is some evidence for the presence of images in early Christian churches, it is harder to find evidence that the early Christians actively venerated these images. One could infer from the presence of these images that the early Christians venerated them but this is not evidence of the active veneration of the images. Later in this article, we will see that given Second Temple Judaism’s use of images there is reason to assume a continuity of practice which would provide the basis for the Christian veneration of icons.

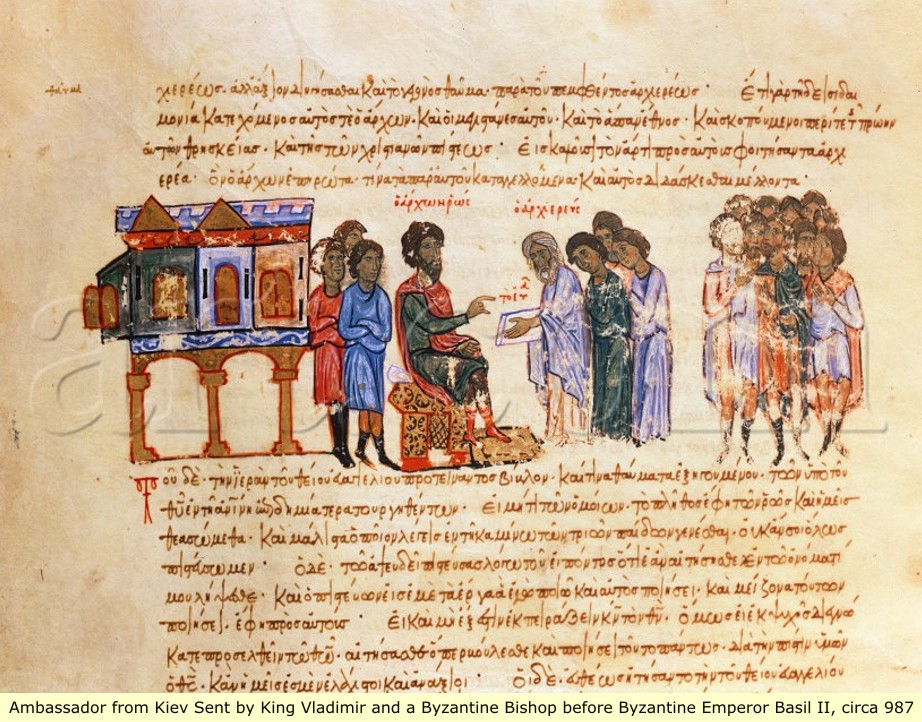

Given the paucity of evidence for the active veneration preceding Emperor Constantine’s recognition of Christianity, the more cautious position to take is that early Christianity was originally aniconic and that the active veneration of icons emerged at a later date. It is hypothesized that the active veneration of images by Christians had two sources: early Christian aniconism and the cult of the martyrs, both of which had roots in Judaism. These two strands of Jewish traditions were retained by the early Christians and transformed through the prism of Christ’s Incarnation and Resurrection. The convergence likely took place in the sixth and seventh centuries when images of the martyrs shifted from being visual reminders into visual sacraments by which one could pray to the saints. Pagoulatos dated the introduction of images in Christian worship between the fifth and seventh centuries (p. 26). The convergence was initially a bottom-up phenomenon, that is, they sprung up among the laity independently of the hierarchy. It was only later that the Church’s hierarchy formally endorsed the veneration of icons at the Council of Nicea II in 787. This continuity with growth points to the dynamic nature of Orthodox Tradition.

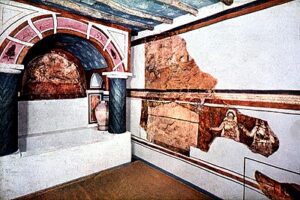

Three Youths in Furnace – Christian Catacombs in Rome

The Cult of Martyrs

The cult of the martyrs has roots in pre-Christian Judaism. 2 Maccabees 7, which dates to 124 BC, recounts the courage of a mother’s seven sons who refused to eat pork because of their religious conviction. This incident was alluded to in Hebrews 11:35, which recounted the many instances of Old Testament saints’ faithfulness to Yahweh. The early Christian cult of the martyrs emerged as early as 155/156 with the early Christians treasuring the bones of Bishop Polycarp and coming together to celebrate the anniversary of his martyrdom (see The Martyrdom of Polycarp chapter 18).

One very early indication of the religious use of images can be found in the Acts of John, a Gnostic text dating to the early second century and regarded as part of the New Testament Apocrypha. In it is an account of a certain Lycomedes who commissioned a portrait of the Apostle John, then hung it in his bedroom with a garland of flowers (§27-28). While outside the pale of orthodox Christianity, this text points to the presence of what Rev. Carpenter would call “iconography” around the time of early Christianity.

Virgin with Child – Catacomb in Rome circa 200s

Another early evidence for the veneration of saints is Rylands Papyrus 470 which has been dated circa 250 – about the same time as the Dura Europos church. On this third century papyrus was a prayer addressed to Mary asking for her aid. See my article “An Early Christian Prayer to Mary.” One possibility is that the early Christians prayed to Mary apart from images and that it was not until the sixth and seventh centuries that there emerged spontaneously among the laity the practice of facing the image of the Virgin Mary when asking for her prayers. The practice of praying to the saint depicted in an icon represents the convergence of the martyr cults with moderate aniconism.

Kissing the Torah. Source

The veneration of icons in the form of kissing icons, a common practice in Orthodoxy, points to Orthodoxy’s historic continuity with Judaism. Kissing holy objects is a widespread practice among Jews. The Virtual Jewish Library notes:

To kiss a holy object displays veneration. This symbolically represents one’s devotion to Judaism and loyalty to God.

In Judaism it is a common practice to kiss the curtain of the Ark (where the Torah scrolls are kept) and to kiss the Torah scroll before reciting the blessing over it. If so, then the kissing of icons would not really be a radical innovation but more an application of a common devotional practice unto the already accepted presence of images in churches. Here we see the process of growth within capital “T” Holy Tradition.

Interior of Solomon’s Temple

The Emergence of Icon Veneration

Christian aniconism had roots in continuity with Judaism. Even with the Second Commandment’s prohibition of graven images, the Old Testament was not iconoclastic as evidenced by God commanding the installation of images in the Tabernacle in Exodus and later in Solomon’s Temple (Exodus 26:31-33; 2 Chronicles 3:7, 14; 1 Kings 6:29-32). From this precedent in the Temple, the Jews would continue to make use of images in the synagogues. Moderate aniconism in early Judaism prepared the way for the active veneration of icons. See my article “Early Jewish Attitudes Toward Images.”

Leslie Brubaker in Inventing Byzantine Iconoclasm (2012) notes that towards the end of the seventh century the Byzantine world saw a shift to a more positive attitude towards images. Among the laity there emerged the widespread practice of asking the martyrs aid as well as the use of candle, curtains, and incense to honor these images (p. 14). The veneration of icons in the 600s followed the passing of Graeco-Roman polytheism along with its depictions of pagan deities. Up until then the veneration of Christian portraits was avoided on the basis that it might be construed as “acting pagan” (Brubaker p. 13). What was new was not the sacred portraits, but their new function in Christian devotional practice (Brubaker p. 110).

One of the earliest evidences of the active veneration of icons can be found in a story in circulation in Constantinople in the mid or late 600s. The story goes that a soldier about to go into battle stood before a portrait of Saint George and spoke to Saint George as if he were there in person. That soldier miraculously survived the battle where thousands perished (Brubaker p. 14). In 626, the city of Constantinople successfully withstood attacks from the Avars and the Persians. The success was attributed to a miraculous icon, an icon not made by human hands (Brubaker p. 15). Brubaker views the rise of the veneration of icons as a response to the general climate of anxiety at the time.

This practice of praying to icons likely stemmed from the convergence of two streams within early Christianity: moderate aniconism and the cult of the martyrs. Both streams had pre-Christian roots in Judaism. Moderate aniconism was already present in Jewish synagogues and reverence for martyrs can be found in 2 Maccabees 7 (which has been dated to circa 124 BCE). The convergence of the two devotional practices took place among the laity independently of the clergy. The convergence of religious devotional practices stirred up resistance among the rigorist aniconists which would explain the presence of rigorous aniconism in early Christianity. In other words, rigorous aniconism was a reaction, not an established position of the early Church.

The Iconoclastic Reaction

This active veneration of icons among the laity sparked resistance among the clergy. The first recorded use of the word “iconoclast” was in a letter dated in the 720s to rebuke a bishop who had removed religious portraits without authorization (Brubaker p. 3). In the early 700s, Constantine, bishop of Nakoleia, was censured by Germanos, Patriarch of Constantinople, for refusing to honor icons by bowing before them. Thomas, bishop of Klaudioupolis, was chided by Germanos for removing icons from his churches (Brubaker pp. 22-24). The novelty here seems to lie with the iconoclasts’ hostility to icons than to the introduction of icons. One significant aspect of the iconoclastic controversy is the absence of objections to the introduction of icons. Rather, the controversy began with people objecting to the removal of already existent icons.

Much of the iconoclastic controversy centered on the sacramental nature of relics and icons. Were the martyrs truly present in their relics and in the icons that depicted them?

The ‘real presence’ of saints offered by miracle-working relics and images not-made-by-human-hands was expanded to include portraits painted by living people . . . . (Brubaker p. 18)

The Byzantine iconoclasts in reaction to popular piety which believed in the real presence of the saints in their portraits sought to emphasize the role of the clergy as intermediaries. Brubaker points out that it is questionable—in light of the available historical evidence—that the Byzantine iconoclasts engaged in the widespread destruction of icons attributed to them (pp. 120-124).

It should also be kept in mind that the 600s were times of anxiety for the Byzantine Empire. By the mid 600s, Arabs had conquered Egypt, the breadbasket of the Roman Empire. There were fears that the end of the world was near. This atmosphere of anxiety led to attempts to purify and regulate secular and religious affairs. The Quinisext Council of 691/2 issued regulation on religious images, e.g., prohibiting the decorating of floors with the cross (Canon 73) and the requirement that Christ be depicted in human form rather than symbolically (Canon 82). Brubaker notes:

While the urge to control and regulate is symptomatic of this unease, the decision to focus on the control of images is a direct response to the power of icons . . . . (p. 17)

The development of Tradition allows for a plurality of opinions until a theological crisis precipitates the refinement of what the Church believes resulting in the formal statement of dogma. The iconoclastic controversy led to the deepening of the early Church’s understanding of the implications of Christ’s Incarnation. One example of early Christian rigorist aniconism was Clement of Alexandria who opposed images on philosophical grounds. Gaifman notes:

Central to Robin Jensen’s argument is a notable distinction between narrative images and images used and venerated in worship. The former, such as scenes from the Bible on sarcophagi, were never a target of anti-iconism, and the argument against the latter was based on classical philosophers (often Plato), for instance the aneikoniston argument of Clement of Alexandria about the impossibility of representing the invisible God in visible form mentioned in the first part of this article. [Gaifman; emphasis added.]

It would not be until the iconoclastic controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries that early Christian theologians realized the implications of the Incarnation. John of Damascus (676-749) wrote:

When the Invisible One becomes visible to flesh, you may then draw a likeness of His form. When He who is a pure spirit, without form or limit, immeasurable in the boundlessness of His own nature, existing as God, takes upon Himself the form of a servant in substance and in stature, and a body of flesh, then you may draw His likeness, and show it to anyone willing to contemplate it. Depict His ineffable condescension, His virginal birth, His baptism in the Jordan, His transfiguration on Thabor, His all-powerful sufferings, His death and miracles, the proofs of His Godhead, the deeds which He worked in the flesh through divine power, His saving Cross, His Sepulchre, and resurrection, and ascent into heaven. Give to it all the endurance of engraving and colour. (John of Damascus)

The transition from the Platonism of Clement of Alexandria in the early third century to that of John of Damascus in the early eighth century illustrates the development of the Church’s understanding of the Incarnation and the ramifications it had for the use of images in churches. Indeed, given the historic Jewish influence on the early Church and the contemporary Muslim’s gnostic hostility to all images, the Church Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council had a far better comparative context—than the Calvinists—by which to assess the nature and function of icons, and also the implications of the Incarnation of Christ for the salvation of humanity and the material universe.

How one views the development of doctrine in the 600s and 700s depends on one’s church affiliation. For many Protestants, Christianity of the seventh century occurred long after Constantine’s conversion in the early 300s which makes it very late and therefore highly suspect. For Orthodox Christians, early Christianity spanned from the Apostolic Fathers of the second century to the period of the Seven Ecumenical Councils which concluded with the Triumph of Orthodoxy in 843. Orthodoxy views church history as one continuing flow unlike Protestantism which views church history in terms of two broken pieces resulting from some vague and unproven “fall” of the Church.

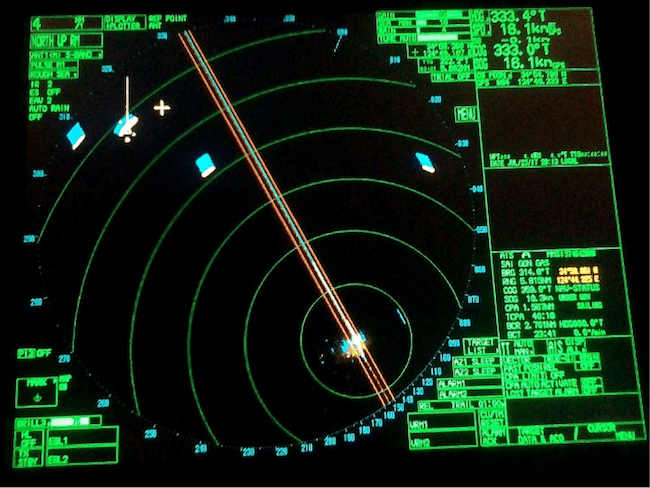

Baptistry – Dura-Europos Church

Reassessing the Dura Europos Images

John Carpenter points out the somewhat curious fact that the religious images at the Dura Europos church were to be found primarily in the baptistery, not in the large hall where assemblies were held. He cites the well-respected Orthodox apologist Steven Bigham’s book Early Christian Attitudes towards Images (p. 68). Carpenter also cites Michael Peppard who wrote The world’s oldest church: Bible, art, and ritual at Dura-Europos (2016). Peppard notes that the large assembly hall which could hold some seventy-five people contained a few graffiti but no “formal paintings” (pp. 17-18). Carpenter takes this as clear cut evidence for rigorous aniconism.

However, the situation is not all that simple. It should be noted, however, that the room’s eastern wall was not preserved leaving open the possibility that that wall had images on it. This strongly warns against making the four-bare-walls argument. The simplest explanation for the apparent iconoclasm was the illegal status of early Christianity. Dura Europos was a military outpost. Peppard underscored the fact that anywhere from a quarter to half of the town’s population were associated with the military garrison (p. 21). Bigham was aware of this possibility. Soon after noting that main hall of the early church was devoid of images, he explains:

The respective situation of the two religions is clearly set out by these two buildings: Judaism was a legal, rich and ancient religion having many adherents; Christianity, on the other hand, was an illegal, poor and new religion having few adherents (p. 69).

Thus, the likely reason for the absence of images was prudence, not iconoclasm. To openly depict Christian images might invite investigation and prosecution in times of persecution. It is somewhat surprising that Rev. Carpenter cites Bigham in support of Reformed iconoclasm (see footnote no. 45), but then failed to take note of the explanation that Bigham gives for the absence of images. Either Rev. Carpenter was hasty in his research or he conveniently passed over the explanation to gain an advantage in the debate. This is not a minor failing in scholarship. This lapse in scholarship is something that John Carpenter needs to address in a future article.

Determining the meaning of the Dura Europos images is not a simple matter given that they are interpreted through the perspectives of theological beliefs. Far from viewing the Dura Europos images as mere decoration (which would support Carpenter’s Reformed iconoclasm), Peppard in his conclusion argues that the images depicted in the baptistery were charged with theological significance.

In my overall interpretation of the artistic and ritual program of the Dura-Europos baptistery, these Christians emphasized salvation as victory, empowerment, healing, refreshment, marriage, illumination, and incarnation more than participation in a ritualized death. In early eastern Christianity, and especially before a cruciform spirituality began to radiate out from Jerusalem’s pilgrimage center, salvation was more likely to be conceived through “birth mysticism” than “death mysticism.” (p. 198)

One of the thrills of scholarship is discovering new authors. John Carpenter cites Michael Peppard’s book to bolster his argument for iconoclasm. Not being acquainted with Peppard, I read his book and came across passages that weakened Carpenter’s argument. Reading Peppard led me to two other scholars, Michael Squire and Steven Shoemaker, who enriched my understanding of the complex relations between religion, art, and text in ways that supported the Orthodox approach to icons. Here, I suspect that John Carpenter in his haste read his sources superficially overlooking the destabilizing implications of their findings.

Peppard offers some startling and even unsettling insights about how the Reformed tradition understands the relations between text and image. He quotes from Michael Squire’s critique of modern western analysis of ancient art:

. . .the critical problem . . . stems from the reductive definition of the image as simply a mode of communication after the manner of words. It is a definition that descends from the theology of Reformed Christianity, with its emphasis on the invisibility of faith and its faith in invisibility. (Squire in Peppard p. 196)

Following that, Peppard makes another provocative observation of the Protestant understanding of the visual arts:

Squire places the blame for our common privileging of text over image — and both of these over ritual — squarely at the feet of the Reformation, which itself was dependent on the printing press and the concomitant logocentric revolution. He aphorizes, “One simply could not be a Protestant in the Graeco-Roman world.” (p. 196)

To sum up, John Carpenter’s aniconic argument far from bolstering Reformed iconoclasm, actually weakens it. This suggests that it is time for Reformed pastors and theologians to reassess Reformed iconoclasm.

What I found surprising in Peppard’s conclusion is his bringing in the Orthodox understanding of salvation. He quotes from the historian Stephen Shoemaker who wrote:

It is through God’s joining Godself to the Creation and to the human race that both are again made whole and restored to God. . . . Human nature is healed by the Immortal One’s condescension to unite with the human race in the Incarnation, allowing the recreation, the recapitulation, as Irenaeus calls it, of humankind. . . . Far more important — and constant — in Eastern Christian soteriology is the notion of ultimate unification with God that is made possible through the act of Incarnation, rather than any compensation due to the devil or, in the case of Anselm [centuries later], the satisfaction of a debt that God must collect through the suffering and sacrifice of the Crucifixion. (Shoemaker in Peppard p. 198)

In footnote 66 (p. 245), Peppard cites Gerasimos P. Pagoulatos who argues that the baptisms carried out in the Dura Europos church represent “the earliest known iconophile service” (in Peppard p. 245). Pagoulatos notes:

The Byzantine service of Christ the Bridegroom as it appears in the third-century sources (that is, the initiation service of the Dura-Europos Christian House Baptistery), constitutes the earliest known Christian service that employed the arts in the communication of knowledge. The third-century service of Dura-Europos Christian Baptistery lies at the origins of a tradition of inclusive epistemology (use of word and image) and anthropology (human mind, body and the senses) in the communication of knowledge that continued later in Byzantium and today’s living tradition of Hellenism. Unlike Western theory and practice (with the exceptions mentioned above), images in Byzantium and in the Orthodox Church of today are thought to reveal divine knowledge. (Pagoulatos p. xxii)

As the later analysis will indicate, Christian apologists of the first three centuries, following Plato, criticised the use of images of gods in pagan Greek religion, implying a spiritual kind of Christian worship far from pagan superstitions. Nevertheless, in pre-Constantinian Christianity one may trace evidence for a type of Christian worship that used images and material means to transmit divine knowledge to the entire human being. (Pagoulatos p. 25)

This finding must surely give apologists like John Carpenter reasons to reconsider their advocacy of Reformed iconoclasm.

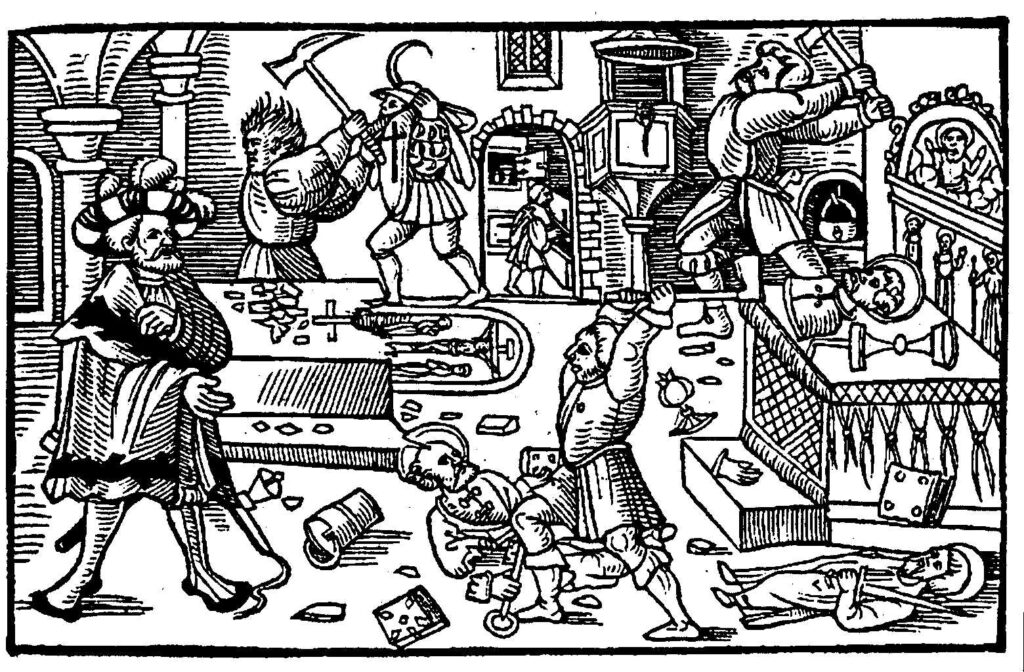

Iconoclasm and the English Reformation

Implications for the Reformed Iconoclasm

Early Christian aniconism presents a serious challenge to Reformed iconoclasm. While rigorous aniconism can result in the exclusion of images, there is no archaeological evidence that early Christian churches were totally devoid of images. Reformed apologists like Rev. Carpenter will need to present archaeological evidence that shows that the norm among early churches were four bare walls like modern-day Reformed churches. As it stands now, the very presence of images in the Dura Europos church baptistery and the catacomb churches of Rome undermine Reformed iconoclasm. This leads to the conclusion that Reformed iconoclasm lacks historical precedent in the early Church.

One striking aspect of Pastor Carpenter’s article is his position that the Old Testament and early Jewish and Christian attitudes towards images were aniconic. This apparent openness to images marks a shift away from the Reformed tradition’s iconoclasm. Furthermore, it suggests that early Christian aniconism is more consistent with the Anglican and Lutheran traditions which allowed for images in places of worship than the Reformed tradition which formally rejects icons (Heidelberg Catechism Questions 97 and 98; Second Helvetic Confession Chapter 4; Westminster Shorter Catechism Question 51; the Westminster Larger Catechism Questions 107 and 108; and the Westminster Confession of Faith Chapter 23).

I suspect that the reason why Rev. Carpenter has devoted so much attention to refuting icons is because iconoclasm is the most visible marker of Reformed worship. Thus, contemporary Orthodox apologia has given considerable attention to the defense of icons because the Reformed tradition has made such a big deal of icons. We have also done so because of the pervasive influence of Reformed iconoclasm on Protestantism in the U.S. Orthodox apologetics has devoted considerable attention to defending icons because Reformed iconoclasm has prevented many inquirers from converting to Orthodoxy. Once a Calvinist is convinced that icons have a biblical basis and are consistent with historic Christianity then the door opens to converting to Orthodoxy.

Roman Catacombs circa 200s

Static Tradition or Development of Doctrine?

While Rev. Carpenter’s recent article shows a more balanced response to Orthodox pro-icon apologia, one weakness still persists – the partisan, oversimplified understanding of Tradition. In reading the recent article one might get the false impression Orthodox tradition is fixed and static. Carpenter concludes his latest article noting:

Perhaps most revealing, Eastern Orthodox claims notwithstanding, is the absolute lack of any description of anything like iconography by anyone in the early church. As yet, I’ve found no evidence of an early Christian using icons. Hence, the supposed strong point of Eastern Orthodoxy, their raison d’être for many evangelical converts to Orthodoxy, their claim to continuity with the early church, is actually their Achilles’ heel. At least as far as icons are concerned, their claim to continuity is baseless. Their practices are, in fact, in direct contradiction to the consistent convictions and practices of the early church. (Carpenter 2018; §9)

This regrettably is a straw man fallacy. Rev. Carpenter constructed the straw man through two tactics: (1) insisting on “early” evidence of images being used in Christian worship and (2) defining “early” Christianity as the period prior to Augustine of Hippo (354-430) (Note 8; Carpenter 2018). Carpenter’s definition of early Christianity has two weaknesses. First, it is quite arbitrary. Generally speaking, church history has been broken down into the following periods: the Apostolic Age (33 to 100), the Ante-Nicene Period (100 to 313), the First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325 to 787) with the Middle Ages commencing in 800. Source. Rev. Carpenter’s approach to early church history using Augustine as a major demarcation point is eccentric to say the least. Second, his arbitrary dating excludes important evidences like the writings of John of Damascus (676-749), Theodore the Studite (769-826), and the Council of Nicea II (787). In short, John Carpenter ignores or excludes much of the evidences right in front of him in order to stack the deck in his favor.

The Straw Man Argument Yet Again

Thus, for all the improvements in John Carpenter’s pro-Reformed apologia, several weaknesses remain: an ahistoric, static understanding of Orthodox Tradition and a refusal to consider evidences that point to historical continuity within Orthodox Tradition. This is much like to criticisms I made in my 2013 article: “Clearing the Way for Reformed-Orthodox Dialogue on Icons.” Here I reiterate what I wrote then:

What Rev. Carpenter wrote reflects a misunderstanding among Protestants as to how Orthodox Christians understand Tradition. This belief that Orthodoxy’s claim “unbroken continuity” leaves absolutely no allowance or room for any development has been a significant impediment to Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. Steven Bigham in Early Christian Attitudes toward Images (2004) counters that false characterization noting:

Few defenders of the idea of Tradition claim that nothing has changed since the beginning of the Church, and everyone recognizes that all the changes that have taken place have not necessarily been for the good. . . . . A healthy doctrine of Holy Tradition makes a place for changes, and even corruption and restoration, throughout history while still affirming an essential continuity and purity. This concept is otherwise known as indefectibility: the gates of hell will not prevail against the Church. This theoretical framework, indefectibility, takes change and evolution into account but denies that there has been or can be a rupture or corruption of Holy Tradition itself (p. 15; emphasis added).

Rev. Carpenter’s static understanding of Tradition raises all sorts of problems. By that definition then the Nicene Creed can be considered an innovative add on. Furthermore, it would imply that the term “Trinity”–which cannot be found in the Bible—can be considered a departure from Apostolic Tradition. Also, for the first several centuries the New Testament canon was an open question with some books included by some churches and other books left out by others. It was not until the Sixth Ecumenical Council formally defined the New Testament canon that the listing was formally closed. All this goes to show that there is an element of elaboration and development of doctrine and practice in early Christianity that does no violence to indefectibility or unbroken-continuity. Carpenter’s portrayal of the Orthodox understanding of Tradition as static is historically incorrect and leads him to set up a straw man argument.

Living Mango Tree

Shifting the Focus of Reformed-Orthodox Dialogue

While icons may represent the most visible difference between the Reformed tradition and Orthodoxy, they do not constitute the most important difference. Of greater importance to Orthodoxy claim to apostolic continuity are: (1) continuity in worship, especially the Eucharist, and (2) continuity in apostolic succession via the episcopacy. I wrote in my 2013 response to John Carpenter:

If Pastor Carpenter wishes to challenge Orthodoxy’s claim to unbroken apostolic continuity, he should marshal his arguments against two claims made by the Orthodox Church: (1) its claim to unbroken episcopal succession from the original Apostles to the present day and (2) its teaching of the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist. For Orthodoxy the episcopacy and the Eucharist form the core of Tradition. Icons, on the other hand, acquired dogmatic significance in the later centuries.

Fossil

Contrary to Carpenter’s depiction of Orthodox Tradition as static continuity, Orthodoxy understands Apostolic Tradition—with the capital “T”, not the lowercase “t”—not static like a fossil, but rather a dynamic continuity much like the continuity one observes in a tiny mango plant growing into a huge, fully grown, fruit-bearing mango tree. Ironically, Carpenter’s introduction of the concept of aniconism has helped me to develop a more nuanced and flexible approach to handling the apparently iconoclastic evidence in early Christianity and to trace the process by which a full-fledged theology of the sacramental nature of icons that is so characteristic of Orthodoxy. It also points to the fact that Reformed-Orthodox dialogue can be fruitful and beneficial to both sides. I look forward to Rev. Carpenter’s future articles and hope that he will give more attention to capital “T” Tradition which constitutes the heart of Orthodoxy. This, not icons, is the core difference between the Reformed tradition and Orthodoxy.

Robert Arakaki

References

Robert Arakaki. 2013. “Clearing the Way for Reformed-Orthodox Dialogue on Icons.” Reformed-OrthodoxBridge.

Robert Arakaki. 2013. “Early Jewish Attitudes Towards Images.” Reformed-OrthodoxBridge.

Robert Arakaki. 2015. “An Early Christian Prayer to Mary.” Reformed-OrthodoxBridge.

Steven Bigham. 2004. Early Christian Attitudes toward Images.

Leslie Brubaker. 2012. Inventing Byzantine Iconoclasm. Bristol Classical Library.

Milette Gaifman’s 2017 article: “Aniconism: definitions, examples and comparative perspectives.”

Acts of John. §27 [Early Gnostic document]

Jewish Virtual Library. “Jewish Practices & Rituals: Kissing Holy Objects.”

John of Damascus. Apologia Against Those Who Decry Holy Images. Fordham University.

Gerasimos P. Pagoulatos. 2009. Tracing the Bridegroom in Dura: The Bridal Initiation Service of the Dura Europos Christian Baptistery as Early Evidence of the Use of Images in Christian and Byzantine Worship.

Michael Peppard. 2016. The world’s oldest church: Bible, art, and ritual at Dura-Europos.

Stephen J. Shoemaker. 2008. Between Scripture And Tradition: The Marian Apocrypha Of Early Christianity in The Reception and Interpretation of the Bible in Late Antiquity.

Michael Squire. 2009. Image and Text in Graeco-Roman Antiquity.

Recent Comments