Response to Michael Horton — Are Eastern Orthodoxy and Evangelicalism Compatible? NO

Rev. Michael Horton

In this blog posting I will be responding to Pastor Michael Horton’s chapter in Three Views on Eastern Orthodoxy and Evangelicalism “Are Eastern Orthodoxy and Evangelicalism Compatible? NO.”

Pastor Michael Horton is a prominent leader among Reformed Christians. His position is that Eastern Orthodoxy and the Reformed faith are incompatible.

Horton divides his essay into two parts: Range of Agreements and Range of Disagreements. I will be structuring this review differently discussing first the material principle (core beliefs) of Pastor Horton’s theology then the formal principle of his theology (source of beliefs).

I. Material Principle — Justification By Faith Alone

Pastor Horton identifies the core difference to be Protestantism’s material principle: justification by grace alone through faith alone because of Christ alone (p. 128). For Horton the principle of sola fide is so important that any moderation of this principle is tantamount to apostasy. He writes:

Any view of union and recapitulation that denies that the sole basis for divine acceptance of sinners is the righteousness of Christ and that the sole means of receiving that righteousness is imputation through faith alone apart from works is a denial of the gospel (p. 137; emphasis added).

The Orthodox response to Horton’s position is four fold: (1) we affirm justification by faith, (2) we deny justification by faith alone (sola fide), (3) from the standpoint of historical theology sola fide is a doctrinal novelty, something never taught by the church fathers, and (4) by making sola fide the litmus test of orthodoxy Protestantism has introduced a divisive element into Christianity.

I.A. Orthodox Affirmation of Justification by Faith

The Confession of Dositheus (1672) represents the Orthodox Church’s official response to Reformed theology. In it we find ample proofs of the Orthodox Church’s belief in justification through faith in Christ. Decree VIII contains a description of Christ’s salvific death on the Cross that any Evangelical would assent to:

We believe our Lord Jesus Christ to be the only mediator, and that in giving Himself a ransom for all He hath through His own Blood made a reconciliation between God and man, and that Himself having a care for His own is advocate and propitiation for our sins (Leith pp. 490-491).

That the Orthodox Church teaches justification by faith is clear in Decree IX:

We believe no one to be saved without faith. And by faith we mean the right notion that is in us concerning God and divine things, which, working by love, that is to say by (observing) the Divine commandments, justifieth us with Christ; and without this (faith) it is impossible to please God (Leith p. 491).

The Orthodox Church affirms justification by faith in Christ because it is taught in Scripture. The Lectionary lists Romans 5:1-10 as the epistle reading for the third Sunday after Pentecost and Galatians 2:16-20 as the epistle reading for the twenty first Sunday after Pentecost. These readings are obligatory for all Orthodox churches. In them we learn that through faith in Christ we are justified and reconciled to God. Therefore, justification by faith is not a hidden or overlooked teaching in the Orthodox Church.

I.B. Orthodox Rejection of Justification by Faith “Alone”

The Confession of Dositheus also makes it clear that the Orthodox Church rejects sola fide:

We believe a man to be not simply justified through faith alone, but through faith which worked through love, that is to say, through faith and works (Decree XIII, Leith p. 496-497).

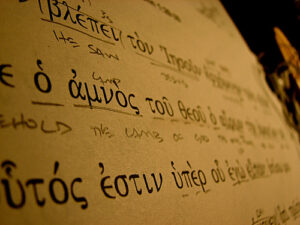

This is consistent with Scripture. Nowhere does Scripture teaches justification by “faith alone.” The only place in Scripture that has the phrase: “faith alone” (πιστεως μονον) is James 2:24, or its equivalent: “faith apart from works” (η πιστις χωρις των εργων) in James 2:20 or 2:26, or “faith by itself” (η πιστις…. καθ εαυτην) in James 2:17. James’ epistle is most pertinent to the sola fide controversy because it speaks directly to the issue of faith versus good works. For James faith without works is “dead” (2:17), “useless” (2:20), or “like a body without the spirit” (2:26) (NIV translation).

When we read Romans and Galatians we need to keep in mind that in most instances “works” refer to the good deeds enjoined by the Jewish Torah. Paul was not referring to good deeds that would earn us merit before God; this medieval understanding of good deeds is alien to first century Christianity. When Paul wrote about righteousness in Romans and Galatians he had in mind covenantal righteousness. The Orthodox Study Bible has the following explanatory note that addresses the polarization of faith and works:.

Justification–being or becoming righteous–by faith in God is part of being brought into a covenant relationship Him. Whereas Israel was under the old covenant, in which salvation came through faith as revealed in the law, the Church is under the new covenant. Salvation comes through faith in Christ, who fulfills the law. (“Justification by Faith” in the Orthodox Study Bible, p. 1259)

The root meaning of “righteousness” is “right relationship.” The major issue facing the early Church was whether one could have a “right relationship” with God apart from the Jewish Torah. In other words, could the Gentiles have a right relationship or covenant standing just on the basis of faith in Jesus as the Christ? The Judaizers answered in the negative; Paul answered in the affirmative.

I.C. Justification by Faith Alone From a Historical Standpoint

Probably what upsets Horton is Orthodoxy’s willingness to allow a plurality of paradigms for explaining our salvation in Christ: economic, therapeutic, covenantal, military, pedagogical, and forensic. The early Church dogmatized on Christology and the Trinity but it did not dogmatize on soteriology. Protestantism assumes that there was a clear and definite teaching of sola fide in the early church, but the historical evidence does not support that assumption. Justification was not a theological issue in the pre-Augustinian tradition (McGrath 1986a:19). Alister McGrath’s magisterial Iustitia Dei: A history of the Christian doctrine of Justification draws attention to the fact that for the first three hundred fifty years the church’s teaching on justification was “inchoate and ill-defined” (see McGrath 1986a:23). J.N.D. Kelly notes that there were a variety of competing theories of salvation in the early church, even within the same theologian! (1960:375) In other words, the early Church did not teach sola fide! If Pastor Horton wishes to dispute these observations all he needs to do is provide evidence from the Church Fathers or councils in support of sola fide.

Much of the early Christians’ understanding of salvation was influenced by the Incarnation. This is the idea of Christ as the Second Adam recapitulating or summing up human existence. J.N.D. Kelly wrote in Early Christian Doctrines:

Running through almost all the patristic attempts to explain the redemption there is one grand theme which, we suggest, provides the clue to the fathers’ understanding of the work of Christ. This is none other than the ancient idea of recapitulation which Irenaeus derived from St. Paul, and which envisages Christ as the representative of the entire race. . . . . The various forms of the sacrificial theory frankly presupposes it, using it to explain how Christ can act for us in the ways of substitution and reconciliation. The theory of the Devil’s rights might seem to move on a rather different plane, but it too assumes that, as the representative man, Christ is a fitting exchange for mankind held in the Devil’s grasp (1960:376-377).

This linking of our salvation with Christ’s Incarnation can also be seen in the Nicene Creed:

For us and for our salvation He came down from heaven and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and became man (Emphasis added).

This line is the only place where the word “salvation” (σωτεριαν) is used in the Nicene Creed. It is telling that the word salvation is linked especially with the Incarnation. It is important that the word “Incarnation” not be read narrowly, but broadly, that is, encompassing Christ’s birth, life and ministry, but also his death on the Cross and his third day Resurrection. Where Protestants tend to base salvation in Christ’s death on the Cross, Orthodoxy base our salvation in the totality of the arc of Christ’s Incarnate existence.

The difference of opinion between the Orthodox and Protestantism can be traced to the different historical trajectory of their respective theologies. The Byzantine East never experienced a controversy similar to the one over Pelagianism in the Latin West. It is important to keep in mind that Anselm of Canterbury’s Cur Deus Homo introduced a strong forensic emphasis to Western Christianity. This influential paradigm was published in 1097, after the Great Schism of 1054. Then there took place a wide ranging and in depth discussion about soteriology in medieval period which would result in Western Christianity moving further away from its patristic roots. (See chapter 3 “The Plan of Salvation” in Pelikan’s The Growth of Medieval Theology, Vol. 3) In these discussions “works” came to be understood in the context of moral law, not the Jewish Torah. Especially pivotal was the debate over meritum de condigno (an act that was worthy of divine acceptance) versus meritum de congruo (an act that was accepted because of the mere generosity of God) (See Oberman’s The Harvest of Medieval Theology 1963: 471-472, 42-44). Out of these wide ranging discussions would emerge the backdrop for Protestantism’s distinctive soteriology.

Horton’s reading of Romans is based upon the assumption that Paul was writing about justification as freedom from good works, not in a more narrow sense of freedom from the Jewish ceremonial law (McGrath 1986a:22). McGrath notes about the earliest known Latin commentary on Romans composed by “Ambrosiaster“:

Most modern commentators on this important work recognise that its exposition of the doctrine of justification by faith is grounded in the contrast between Christianity and Judaism: there is no trace of a more universal interpretation of justification by faith meaning freedom from a law of works — merely freedom from the Jewish ceremonial law (McGrath 1986a:22).

With respect to the novelty of sola fide Jaroslav Pelikan noted that while the Protestant Reformers used terms familiar to earlier Christians: “church,” “gospel,” and “grace,” they understood these terms in ways unrecognizable by their predecessors (1984:128). Alister McGrath makes the following observations about the novel nature of the Protestant understanding of justification:

The most accurate description of the doctrine of justification associated with the Reformed and Lutheran churches from 1530 onwards is that they represent a radically new interpretation of the Pauline concept of ‘imputed righteousness’ set within an Augustinian soteriological framework (McGrath 1986b:2; emphasis added).

The Protestant understanding of the nature of justification represents a theological novum, whereas its understanding of its mode was not. It is therefore of considerable importance to appreciate that the criterion employed in the sixteenth century to determine whether a particular doctrine of justification was Protestant or otherwise was whether justification was understood forensically (1986a:184; italics in original).

Thus, one important reason why such a huge gap in understanding exists between the Reformed tradition and Eastern Orthodoxy is the fact that where Orthodoxy remained close to it patristic roots, the Protestant understanding of the Gospel reflects the considerable theological evolution that took place in western medieval Catholicism.

While the Protestant Reformers believed they recovered the gospel, what they did was to turn a novel doctrine sola fide into a dogma. It is a novelty because none of the early Church Fathers taught sola fide; and it is a dogma in that the Reformers used it as a litmus test determining whether or not one’s theology is authentically Christian. For the Orthodox the notion of a novel dogma is an oxymoron, an absurdity. The dogmas — fundamental beliefs — can never be novel because they must be rooted in the apostolic teaching and accepted by the patristic consensus or affirmed by an Ecumenical Council. What Horton and the Reformers have done is to elevate a novel interpretation of Augustinian soteriology to a fundamental dogma like the Trinity and by making it a litmus test for orthodoxy alienated themselves from the early church.

Crucifixion – Western Depiction

I.D. Is Orthodoxy Opposed to the Forensic Model?

The forensic paradigm is so important to Horton that he writes:

If we do not grasp the representative, legal, covenantal nature of Paul’s argument with reference to the imputation of original sin, we cannot comprehend the imputation of Christ’s perfect obedience as the second Adam. That is to say, original sin and justification are bound up together as corollaries in this passage, and to misunderstand one is to misunderstand the other (p. 160).

Eastern Orthodoxy has never denied the forensic element of our salvation in Christ. Rather it is reluctant to make the forensic paradigm the benchmark for theological orthodoxy as was done by the Reformers. It may be that Horton’s experience with contemporary Orthodox theologians has led him to believe that Eastern Orthodoxy is averse to the forensic paradigm of salvation. If that is the case then it is possible that what he experienced was unfounded anti-Western prejudice which would be regrettable.

Crucifixion – Eastern style

Horton quotes Irenaeus of Lyons’ Adversus Haeresis 5.16 (p. 133) to show that the forensic paradigm is part of the early Church teaching and there is no reason why it should not be part of contemporary Orthodox theology. I agree with Horton that Irenaeus used forensic concepts to explain Christ’s death on the Cross. My disagreement with Horton lies with his assumption of sola fide; nowhere did Irenaeus assert sola fide — justification by grace alone through faith alone. If Pastor Horton believes that I am mistaken, he needs to point to the relevant passages in Irenaeus’ writings.

Irenaeus of Lyons was just one of the many church fathers. Daniel Flood’s “Substitutionary atonement and the church fathers” which was published in the Evangelical Quarterly provides a useful and nuanced overview of what various church fathers did and did not teach regarding substitutionary atonement.

Horton cites Callinicos’ catechism as evidence that Orthodoxy does have a place for a forensic approach to salvation (p. 125). I would note that stronger evidence for the forensic paradigm is to be found in the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. In the Completion Litany the congregation prays for the “Forgiveness of our sins and offenses” and for a “good defense before the dread judgment seat of Christ.” The Words of Institution over the bread — “Take, eat, this is my body which is broken for you for the remission of sins.” — uses forensic language. Orthodox Christians are constantly reminded of their depravity by the Pre-Communion prayer: “I believe, Lord, and confess, that you are truly the Christ, Son of the living God, Who came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the greatest.” It should be noted that while the Orthodox Liturgy uses forensic language, it does not present salvation exclusively in terms of forensic justification. Horton’s failure to draw on Orthodoxy’s liturgical tradition indicates that he is not ready to deal with Orthodox Christians on their own ground. It is important in any Orthodox-Reformed dialogue that differences in theological method be addressed along with differences in doctrine.

Reformed Christians who want to assess the Orthodox teaching on salvation in Christ need to be aware of how much Protestant beliefs color their reading of Scripture. Horton points to Colossians 2:13-15 as evidence of the forensic paradigm (p. 132). He notes that “public spectacle” refers to a courtroom scene. But the Greek here δειγματιζω refers to a victor displaying the spoils of war (See Reinecke’s Linguistic Key to the Greek New Testament, Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament Vol. II p. 31). Horton’s faulty reading of the Greek text undermines his single minded reading of the Pauline text and weakens his argument. He ends up simplifying the complexity and diversity of what the Bible teaches.

I.E. Orthodox Doctrine of Synergism

Horton notes that while he takes care to distinguish Eastern Orthodox soteriology from that of Roman Catholicism, what binds the two is the principle of synergism. (Note: “synergism” comes from the Greek “syn” = “with” and “erg” = “work” or “energy”; similarly “cooperate” comes from the Latin “co” = “with” and “opera” = “to do” or “to act.”) He writes:

We do not deny that we cooperate with God’s grace and, by receiving the means of grace (Word and sacrament), grow into maturity in Christ, but we do deny that we can cooperate in our own regeneration (i.e., awakening to God) and justification (i.e., acceptance by God), our will being enslaved to sin until God graciously frees it to embrace Christ and all his benefits. We are not declared righteous because we have cooperated with God’s grace; we are justified “freely by his grace” (Rom. 3:24) so that we can.” (p. 161; emphasis in original).

The Reformed tradition does not deny any and all forms of cooperation with divine grace, just with respect to our justification and regeneration. He writes, “It is trusting in Christ’s merit alone, not in our cooperation with grace, that we are justified.” (p. 135). Orthodoxy takes the position that we must respond to God’s gracious initiative in order for us to be saved. The assumption here that human nature retains the capacity to respond to God’s grace even if the human soul is wounded and corrupted by the Fall

This insistent denial of synergism is closely linked with the belief in man’s total depravity resulting from the Fall. The doctrine of total depravity has its roots in Augustine’s interpretation of the Fall. It should be kept in mind that Orthodoxy and Western Christianity have quite different understands of the Fall. Where Augustine and the West assumed that Adam fell from perfection into utter depravity, Irenaeus and Eastern Orthodoxy believed that Adam fell from a state of immaturity into corruptibility. The Augustinian interpretation was not widely accepted by the early church fathers and never became part of the patristic consensus. With the collapse of the western half of the Roman Empire, Latin Christianity became especially dependent on one theologian, Augustine, resulting in a narrowing of its doctrinal framework. McGrath notes that the Protestant Reformation’s “radical anti-Pelagianism” is an extreme stance that is at odds with the early Church Fathers (see McGrath 1986a:183).

I.F. Original Sin

Icon of the Fall of Mankind

Horton criticizes Orthodoxy for having an inadequate view of sin (p. 129). To make his case he points out that Orthodoxy’s “relational” understanding of salvation has led to the neglect of the “forensic” dimension of salvation (pp. 130-133).

Orthodoxy has many healthy emphases, but its denial of the full seriousness of sin and its consequently high appreciation for the possibilities of free will keep it from recognizing the heart of the gospel (p. 139).

The Orthodox understanding of Original Sin stands somewhere between the two extremes of (1) Pelagius who saw sin as an outward act transgressing the law and who held that man was free to choose to sin or not to sin and (2) Augustine who believed that because we were born sinners we lacked the capacity to do good. The Orthodox understanding of Original Sin is that the guilt of the original transgression was imputed to Adam alone. It believes that the original transgression severed humanity’s primordial communion with God subjecting Adam’s body and soul to corruption and mortality, and that as his descendants we inherited from Adam a fallen human nature. While profoundly affected by the Fall the human race still retained an awareness of God and an awareness of our calling to do good (Romans 1:18-20, 2:14-15).

Horton takes issue with Fr. Berzonsky over the nature of Original Sin. He engages in an exegesis of Roman 5:12-17 drawing attention to Paul’s phrase: εφ ω παντες ημαρτον “because all sinned.” For Horton this passage is important because if he can prove the forensic nature of the Original Sin — that Adam’s guilt was imputed to his posterity — then he can make the case for salvation in Christ as the imputation of his righteousness to those who believe in him. He writes:

How can I be a victim of death’s reign even if I did not commit exactly the same sin as Adam, the very conclusion that Father Berzonsky is unwilling to reach?

Paul’s answer seems to be that I was there with Adam covenantally–“in his loins,” as it were. Even though I was not personally present, I was representatively present in Adam (p. 160; italics added).

One problem with Horton’s reading of Romans 5:12-17 is that Paul did not use the word “covenant” (διαθηκη) in this passage; he did not do so until Romans 9:4 and 11:27. What Horton is attempting to do here is to impose a certain understanding on Paul’s explanation of how Adam’s sin resulted in humanity’s subjection to death and corruption. Pastor Horton seems to be reading Romans from the standpoint of federal theology, a school of thought developed by Johannes Cocceius (1603-1609). While closely associated with Reformed theology, the notion of humanity’s loss of original righteousness being a consequence of Adam’s first sin as the covenantal head of the human race is alien to patristic theology (see G.N.M. Collins’ “Federal Theology” in Evangelical Dictionary of Theology). McGrath notes that covenant theology represents a post-Calvin development in Reformed theology and had the effect of moving Reformed doctrine away from Calvin’s Christological approach to soteriology (1986b:40-41).

I.G. Church Governance

As a Protestant Horton has a low view of the episcopacy. He attributes the Eastern Orthodox office of the bishop to the exigencies of the gnostic controversy (p. 127). However, he fails to mention another very early witness to the episcopacy, Ignatius of Antioch‘s letters (written between 98 and 117). If anything, Ignatius took an even more extreme position insisting that nothing be done apart from the bishop. Another early witness to the episcopacy is Eusebius’ Church History which is filled references to the bishops as successors to the apostles.

Horton’s insistence that direct Biblical evidence be presented for the episcopacy is tendentious. There is no clear cut biblical evidence either for congregationalism or presbyterianism. The fact is Paul’s letters prior to his death show him urging his protégés, Timothy and Titus, to guard the apostolic teaching and to rule over the congregations under their care. There is no evidence that the early church practiced a congregational or presbyterian form of church governance. But there is ample historical evidence in support of the Eastern Orthodox practice.

As a Protestant Horton is skeptical of Eastern Orthodoxy’s claim to apostolic succession. His argument that the Galatian churches defection to the Judaizing heresy undermines confidence in apostolic succession (p. 142) is really a straw man argument. So far as we know the Apostle Paul never anathematized any of the congregations in Galatia and the controversy was in time resolved at the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15). Apostolic succession in Orthodoxy does not rely solely on formal succession of office. For Eastern Orthodoxy apostolic succession cannot be reduced to mere ritual of laying on of hands. There must also be faithfulness to the Apostolic teaching (II Timothy 2:2, 1:13).

When it comes to apostolic succession there are two choices: (1) the monarchy of the Roman papacy or (2) the conciliarity of Eastern Orthodoxy. Protestants have no historical basis for claiming apostolic succession. Horton’s complaint about the pluralism of the early Church, councils contradicting councils as well as church fathers contradicting each other is immature whining (p. 127). What he seems to want is a clear cut and rational means by which one can systematically list which councils and church fathers were orthodox which ones were not. His criteria seems to reflect medieval Scholasticism’s obsession with the construction of logically consistent theological systems. The Orthodox approach is organic and embodied; it is rooted in a theological consensus that is grounded in the historic Church.

Greek New Testament

II. Formal Principle — Scripture and Tradition

Horton asserts that both traditions are compatible on the grounds of formal principle. He points to the fact that the Reformed tradition and the Orthodox are both confessional, utilizing the ecumenical creeds and their respective confessions (p. 118). He also points to Calvin drawing upon the Church Fathers just like the Eastern Orthodox do (p. 119). Horton writes: “One might say that Scripture is the teaching, and tradition is the teacher.” (p. 119) Despite the proximity of the Reformers’ high regard for the early Church Fathers, the fact is the formal principle of the Protestant Reformation is sola scriptura. We find this Horton articulating sola scriptura in the classic sense:

No conscience may be constrained beyond the Word, but the faithful acknowledge the importance of submitting to the church and agreeing together in a unity of confession. (p. 120)

Horton objects to the Orthodox conception of an infallible Scripture being interpreted in light of an infallible tradition asking:

Having an infallible tradition to interpret an infallible text only leave us with deeper difficulties. Who interprets the infallible tradition? (p. 128)

The Orthodox approach to theology is based upon the belief that the Christ promised the Holy Spirit to guide his Church into all truth. Infallibility is a property of the Holy Spirit, the third Person of the Trinity, who inspires Scripture and indwells the Church, the Body of Christ. The Church is understood to be a divine institution founded by Christ. The Confession of Dositheus lays out the Eastern Orthodox understanding that the Holy Spirit inspires both Scripture and Tradition. It goes on to note that because it is indwelt by the Spirit of truth, the Church is infallible. Decree II of the Confession of Dositheus states:

Wherefore, the witness also of the Catholic Church is, we believe, not of inferior authority to that of the Divine Scriptures. For one and the same Holy Spirit being the author of both, it is quite the same to be taught by the Scriptures and by the Catholic Church. …. …it is impossible for her to in any wise err, or to be at all deceive, or be deceived; but like the Divine Scriptures, is infallible, and hath perpetual authority (Decree II, Leith p. 487)

Pastor Horton identifies the Protestantism’s material principle — sola fide — as the key difference between the Reformed and Eastern Orthodox traditions, but I am of the opinion that he underestimates the role of Protestantism’s formal principle as the dividing issue between the two sides.

Conclusion — Awkward Initial Encounters

The Reformed-Orthodox dialogue in Three Views on Eastern Orthodoxy and Evangelicalism is part of a kairos moment. Orthodox and Reformed Christians are like two distantly related cousins who recently discovered each other and are becoming reacquainted. Their separation was the result of a messy family split that took place long ago (the 1054 Schism). As a result of this separation they acquired different habits, values, and ways of doing things. Initial encounters can be awkward. Differences in dress, eating habits, and verbal expressions were often quickly criticized leading to hurt feelings and misunderstanding and stereotypes. We find a range of reactions from the Orthodox contributors to Pastor Horton’s chapter. Bradley Nassif views the problem in terms of an “imbalanced agreement” (p. 146), Edward Rommen notes a strange dissonance of simultaneous agreement and disagreement as he read Horton’s chapter (p. 155), and Vladimir Berzonsky’s curt dismissal that Horton had “no real comprehension of Orthodox Christianity” (p. 149). As both sides continued to reach out to the other and their relationship will soon move to a different level.

One cultural difference between the Orthodox and Reformed traditions is the way they do theology. One problem I have with Horton’s presentation of Orthodox doctrine is his research method, especially his reliance on obscure Orthodox theologians. He cites from V. Palachovsky, Constantine Callinicos and Constantine Tsirplanis authors I never heard of until I read his chapter! I am also bothered by his unfamiliarity with the conciliar and patristic approach that underlie Orthodox theology. What is especially puzzling about the book is the failure by Horton and his fellow respondents to draw on the Confession of Dositheus as a source document for the Eastern Orthodox perspective (See Leith 1963). His frequent citation of modern Orthodox academic theologians rather than liturgical, patristic, and conciliar statements impedes Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. He needs to give reasons for his research methods if he wants to bypass the Orthodox patristic and conciliar approach to doing theology. One last note about theological research; on page 129 in note 23 Horton cites Augustine’s Confession Bk 21 chap. 27 but Confessions has only 13 books! It would be much appreciated if he were clear up the matter.

The other chapters of Three Views provide valuable insights as well. Bradley Nassif raises an important issue of piety or spiritual life. He supports Horton’s call for Orthodoxy to recognize the “evangelical character of the church’s theology” (p. 148). Nassif is worried that due to a neglect of “the importance of preaching personal salvation through faith in Christ and the need for personal Bible study and personal piety” many cradle Orthodox and even converts will leave Orthodoxy for Evangelicalism (p. 148). Nassif’s belief that Evangelical piety can enrich Orthodox Christians evidence a willingness among Orthodox to learn from Evangelicalism.

In closing, I agree with Pastor Horton that Evangelicalism and Eastern Orthodoxy, despite the common ground between the two traditions, are incompatible. By compatible, I mean Eucharistic union. Differences in material and formal principles mean that ecumenical dialogue should aim at mutual understanding and respect, but not ecclesial union. I view Pastor Horton’s chapter in Three Views on Eastern Orthodoxy and Evangelicalism as another beginning step in the dialogue between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions. Even as we discuss our differences, we need to affirm the common ground that we share in Scripture, the church fathers, Christology, and the Trinity. Civility and mutual respect between the two traditions will be much needed in the future as both sides face an increasingly post-Christian society.

Robert Arakaki

See also: Michael Horton’s podcast: “The Lure of Eastern Orthodoxy” and a response by Fullness of Orthodoxy blog.

Bibliography

Collins, G.N.M. 1984. “Federal Theology.” In Evangelical Dictionary of Theology: 413-414. Walter A. Elwell, editor. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Kelly, J.N.D. 1960. Early Christian Doctrines. Revised edition. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers.

Leith, John H. ed. 1963. Creeds of the Churches: A Reader in Christian Doctrine From the Bible to the Present. John H. Leith, editor. Third edition, 1982. Atlanta, Georgia: John Knox Press.

McGrath, Alister E. 1986a. Iustitia Dei: A history of the Christian doctrine of Justification: The Beginnings to the Reformation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

__________. 1986b. Iustitia Dei: A history of the Christian doctrine of Justification: From 1500 to the present day. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Oberman, Heiko A. 1963. The Harvest of Medieval Theology: Gabriel Biel and Late Medieval Nominalism. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Pelikan, Yaroslav. 1978. The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine. Volume 3. The Growth of Medieval Theology (600-1300). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

__________. 1984. The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine. Volume 4. Reformation of Church and Dogma (1300-1700). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

In recent years icons have become a matter of public debate among Protestants and Evangelicals, and Orthodox Christians. Where in the past Protestants thought of icons as an Orthodox peculiarity or a quaint dispute quickly passed over in church history class, they are coming to grips with the fact that icons present a serious theological challenge to their theology. In addition to the discovery that a rereading of Scripture from a different angle can lead to a solid biblical basis for icons, they must also grapple with the implications that ripple out from the historic role of icons in the early Church. Cardinal John Henry Newman’s quip: “”To be deep in history is to cease to be Protestant” might be more true than most have considered! [See my articles: “How an Icon Brought a Calvinist to Orthodoxy” and “The Biblical Basis for Icons.”]

In recent years icons have become a matter of public debate among Protestants and Evangelicals, and Orthodox Christians. Where in the past Protestants thought of icons as an Orthodox peculiarity or a quaint dispute quickly passed over in church history class, they are coming to grips with the fact that icons present a serious theological challenge to their theology. In addition to the discovery that a rereading of Scripture from a different angle can lead to a solid biblical basis for icons, they must also grapple with the implications that ripple out from the historic role of icons in the early Church. Cardinal John Henry Newman’s quip: “”To be deep in history is to cease to be Protestant” might be more true than most have considered! [See my articles: “How an Icon Brought a Calvinist to Orthodoxy” and “The Biblical Basis for Icons.”]

Recent Comments