One common fear is the fear of the unknown.

Many Protestants contemplating becoming Orthodox wonder what Christian discipleship under Holy Tradition will be like. Will I have to believe strange doctrines and do odd rituals? Will I come under a new law and have to earn my salvation?

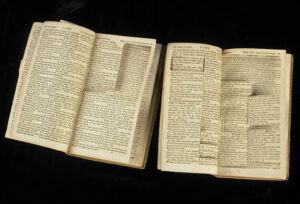

Relinquishing sola scriptura does not mean we stop reading the Bible. We continue to read the Bible but in the context of Holy Tradition. The Orthodox interpretation of Scripture is framed by the Nicene Creed, the Seven Ecumenical Councils, and the consensus of the church fathers. Holy Tradition is not something vague and mysterious. It is a body of beliefs and practices passed on from one generation to the next. Basil the Great, a fourth century church father, described in On the Holy Spirit the Church’s unwritten tradition:

For instance, to take the first and most general example, who is thence who has taught us in writing to sign with the sign of the cross those who have trusted in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ? What writing has taught us to turn to the East at the prayer? Which of the saints has left us in writing the words of the invocation at the displaying of the bread of the Eucharist and the cup of blessing? For we are not, as is well known, content with what the apostle or the Gospel has recorded, but both in preface and conclusion we add other words as being of great importance to the validity of the ministry, and these we derive from unwritten teaching.

Moreover we bless the water of baptism and the oil of the chrism, and besides this the catechumen who is being baptized. On what written authority do we do this? Is not our authority silent and mystical tradition? (Chapter 66)

Orthodoxy claims to have kept the Tradition without change for the past two millennia. This claim can be tested through the study of church history. Entering into an Orthodox Church is like having a “Jurassic Park” experience. We see the ancient Church right before our eyes. It’s nothing at all like what we see in modern Protestant churches! The continuity between the early Church back then and the Orthodox Church today indicates that the Orthodox Church will still be Orthodox one thousand years from now.

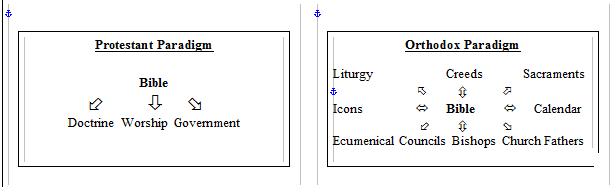

Where Protestantism teaches Scripture over Tradition, Orthodoxy follows the model of Scripture in Tradition. Orthodoxy believes that Apostolic Tradition and Scripture arise from the same source: Jesus Christ. St. Paul admonished the Christians in Thessalonica to “hold fast” to the tradition both in the oral or written form (2 Thessalonians 2:15). St. Paul also referred to his Gospel message, the Eucharist, and Christian propriety as part of the tradition he received and handed down to them (I Corinthians 15:1-4, 11:28, 11:16).

Tradition is not static, but dynamic and organic. It is like a tiny seed that grows into a big tree (Mark 4:30-32). One common misunderstanding is that Tradition means Orthodoxy will do things exactly like the early Church. But when we study church history we find a certain amount of variety and fluidity that in time would evolve into more stable and uniform structures. There are two opposites to living tradition; one is dead formalism and the other is unchecked innovation. The former gives too much priority to the outward form at the expense of the inner life of the Gospel, the latter disregards the importance of the form to preserving and giving expression to the inner life of the Gospel.

The Nicene Creed is a good example of the growth of Tradition. The New Testament writings contained short confessions like: “Jesus is Lord!” This would develop into a confession of faith taught to baptismal candidates who were expected to recite it from memory. While there were local variations, the basic contents of the early creeds were the same. By the time of the First and Second Ecumenical Councils the Creed acquired a fixed form that endures till today known as the Nicene Creed.

When the early Church was confronted with the Arian heresy an ecumenical council was convened in which bishops from all parts of the world came together. They repudiated Arius’ teaching by inserting into the Creed Athanasius’ phrase homoousios, that is, the Son was of the same essence as the Father. Athanasius’ coining “homoousios” might seem innovative, but it was really conservative in intent. Similarly, the coining of “Trinity” was not an innovation, but an attempt to make explicit what had long been understood in the Church’s Tradition.

In matters of controversy the Church gathered in council. The Council of Jerusalem described in Acts 15 set the precedent for the later Ecumenical Councils. Orthodoxy considers the Seven Ecumenical Councils as binding on all its members from the bishops and clergy down to the laity. Orthodoxy relies on Christ’s promise in John 16:13 for its belief that the rulings of the Ecumenical Councils were more than human decisions but the result of the Holy Spirit’s guidance. The fact that the Councils are not optional ensures doctrinal consistency in the Orthodox Church. For a former Protestant who had to live with Protestantism’s doctrinal chaos I find this to be a huge relief.

Tradition informs the leadership structure of the Orthodox Church. The office of the bishop or episcopacy is rooted in the New Testament practice of ordaining qualified men to the priesthood (2 Timothy 2:2) and entrusting them with the “sacred deposit” (2 Timothy 1:13). Irenaeus described how the Christian faith was preserved by means of a chain of apostolic succession. Furthermore, the authority of the bishop was not so much institutional as it was rooted in his faithfulness to Tradition. A bishop unfaithful to Apostolic Tradition would cease to be qualified to hold that office. The office of the bishop was critical to a local church’s claim to be apostolic. ‘No bishop’ = ‘no link’ to the apostles. Without the bishop the local church could not claim to be following the Apostolic teachings or be part of the Church Catholic.

Tradition can be viewed as a matrix made up of several components: the Bible, the Nicene Creed, the Eucharist, the episcopacy, and church councils. These are integrally linked to each other and together uphold each other. In other words, Tradition is a singular Package.

Tradition in the Liturgy

We see Tradition most notably in the Sunday Liturgy.

The first half of the Liturgy is focused on Scripture and thus is called the Liturgy of the Word. The Orthodox Church follows a set of prescribed Scripture readings known as the Lectionary. This ensures that all parishes will share in the same Scripture readings. It also ensures that what the parish hears is not subject to the personal whim of the priest. The Lectionary is like a menu that ensures a balanced diet of spiritual feeding. In many Protestant churches it’s hard to predict what the coming Sunday sermon will be about.

Another important aspect of the Liturgy of the Word is the prayers and hymns. We pray for each other and for the needs of the world. We also remember to pray for our bishop and other clergy. We end the litanies or prayers invoking the name of the Trinity. Several times during the Liturgy the Holy Trinity is mentioned and at that point we make the sign of the Cross. Through regular participation in the Liturgy we become vividly aware of the reality of the Trinity. For much of Protestant worship the Trinity is hardly mentioned at all. For many Protestants the Trinity is something they read about in a book or hear about in a church membership class. This has caused the Trinity to fade from the consciousness of many Protestants.

In the Liturgy the Orthodox Church remembers and honors Mary the Theotokos (God Bearer). The Orthodox Church’s honoring Mary is a way of affirming the Incarnation and also the result of the Third and Fourth Ecumenical Councils’ repudiation of the Nestorian controversy. It is also a way of affirming our fellowship with the great cloud of witnesses in heaven (Hebrews 12:1). To neglect honoring Mary as the Mother of God would be consequential for our theology. It would weaken our appreciation of the Incarnation. Many Protestants view Christ’s Incarnation as a historical event but have very little appreciation of its implication for the Eucharist, the Church as a divine institution, for salvation as recapitulation and deification, and the redemption of the cosmos. Also, not to honor Mary in the Sunday services implies that we honor her in word but not in our actions.

Following the sermon we stand and recite the Nicene Creed. The Nicene Creed unifies us across the world and to other Christians in history. The Creed provides a fence protecting us against heresy. If there is no fence in place a local congregation can become vulnerable to the pastor or a visiting preacher introducing a questionable new teaching.

The second half of the Liturgy, the Eucharist, is rooted in Tradition. St. Paul in I Corinthians 11:23 told the Christians in Corinth that the way he celebrated the Eucharist was based on a tradition that went back to Christ himself. The early Church had a variety of liturgies but by the fifth century the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom became the norm in much of the Greek speaking world. In the early Church the Eucharist was a normal part of the Sunday worship (see The Didache Chapter 14). This stands in contrast to the infrequent observance of the Eucharist in many Protestant churches today.

The second half of the Liturgy, the Eucharist, is rooted in Tradition. St. Paul in I Corinthians 11:23 told the Christians in Corinth that the way he celebrated the Eucharist was based on a tradition that went back to Christ himself. The early Church had a variety of liturgies but by the fifth century the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom became the norm in much of the Greek speaking world. In the early Church the Eucharist was a normal part of the Sunday worship (see The Didache Chapter 14). This stands in contrast to the infrequent observance of the Eucharist in many Protestant churches today.

The Eucharist unites the local church to the Church Catholic. The Eucharist was viewed, not as a mere symbol, but the actual receiving of Christ’s body and blood (Ignatius’ Letter to the Philadelphians Chapter 4). In the early Church the Eucharist could not be celebrated apart from the bishop (Ignatius’ Letter to the Smyrneans Chapter 8). For an Orthodox Christian to go up and receive Holy Communion means that he or she accepts the teachings of the Orthodox Church and that he or she accepts the authority of the bishop.

Holy Tradition — A Way of Life

Holy Tradition is not a set of rules but a way of life. It is the Church living out the teachings of Jesus Christ. It is the culture that has unified Orthodoxy for the past two millennia. Jesus commended fasting (Matthew 6:16-18, Mark 2:20) but did not dictate the specifics of fasting. We learn in the first century church manual called The Didache (Chapter 8) that the early Christians fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays. This spiritual discipline is still followed by the Orthodox Church today. It is not viewed as a quaint practice or for the super spiritual but expected of all Orthodox Christians: laity, clergy, and monastics. We fast as a way of denying ourselves, combating the passions of the flesh, and for our spiritual growth. It is not a way of earning our salvation!

Orthodoxy has a lot of rules, but it is not legalistic. The rule is for Orthodox Christians to fast the night before to prepare for receiving Holy Communion, but there are exceptions to this rule. One is that we don’t keep a spiritual rule if it results in bodily harm. I know of a priest who would withhold Communion to a parishioner if she disobeyed her physician’s instructions to eat on a set schedule! Another exception is that we try to avoid the sin of pharisaism, that is, of putting spirituality over charity. For example, for the Wednesday and Friday fasts we are expected to abstain from meat and dairy product. However, if we are invited to a meal it is better to eat what is set before us than to reject our host’s hospitality. Being Orthodox means not just knowing the rules for spiritual disciplines but more importantly the spirit of charity behind these rules. We fast under the guidance of the parish priest or our spiritual director. It is not advisable that we make up our own rules for fasting.

Holy Tradition consists of little things like making the sign of the Cross, bowing at certain times during the Liturgy, lighting candles, kissing the Bible, venerating icons etc. Orthodox music tend to follow either Byzantine chant or Slavic polyharmonic singing, both done a capella. The general consensus is that musical instruments (whether ‘traditional’ organ or contemporary guitars) and contemporary praise songs are incompatible or inappropriate for Orthodox Liturgy. All this is part of the Orthodox way of life. Those contemplating converting to Orthodoxy must be prepared to make the necessary adjustments. This calls for the relinquishing of the independent spirit and the adoption of an attitude of trust and humility needed for submission to the Church’s authority (Hebrews 13:17).

Two Ways of Joining a Church

When a Protestant decides to join a church body they usually check out the church’s statement of faith, and if they agree with its teachings they join that church. Or they may decide that they like the services the church offers or that the pastor’s sermons help them grow spiritually. In many churches there is a short four to six weeks long membership class that goes over what the church believes.

But in the case of becoming Orthodox people are encouraged to check out the Orthodox Church’s beliefs and its way of life. Catechumens attend the Sunday worship services and take a several months long overview course. An up close look at an Orthodox parish will reveal people who are far from perfect but committed to growing in Christ in the context of His Church. To accept Tradition is not so much agreeing with a theological system as it is entering into a way of life. Converting to Orthodoxy is much like Ruth’s conversion to Yahweh:

Do not ask me to leave you, or turn back from following you; for wherever you go, I will go; and wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God, my God. (Ruth 1:16)

Robert Arakaki

Recent Comments