John Calvin

In an earlier blog posting “Plucking the TULIP,” I marshaled an array of patristic citations showing that a wide range of early church fathers affirmed human free will: Irenaeus of Lyons, Cyril of Jerusalem, John of Damascus, John of the Ladder, Gregory of Nyssa et al. I did this to show that the theological consensus of the early Church refuted the Calvinist doctrine of double predestination.

When I wrote it I wondered how Calvin would have responded to my patristic argument. I recently found the answer when in the course of browsing Calvin’s Institutes I came across the subsection titled “The church fathers generally show less clarity but a tendency to accept freedom of the will. What is free will?” (2.2.4, pp. 258-261)

Calvin opened with the following statement:

All ecclesiastical writers have recognized both that the soundness of reason in man is gravely wounded through sin, and that the will has been very much enslaved by evil desires.

This also reflects the Orthodox understanding of humanity’s fallen condition and our still having free will and the capacity to reason. However, Calvin criticized this understanding of the human condition charging that the early church fathers in affirming human reason came “far too close to the philosophers.” He is of the belief that the early fathers took this position in order to avoid “the jeers of the philosophers.” Then he made the claim the fathers affirmed human free will in order “not to give occasion for slothfulness.” He wrote:

Surely you see by these statements that they credited man with more zeal for virtue than he deserved because they thought that they could not rouse our inborn sluggishness unless they argued that we sinned by it alone.

Dissing the Fathers

Calvin’s low opinion of the Greek fathers comes across loud and clear in the following sentence:

Further, even though the Greeks above the rest—and Chrysostom especially among them—extol the ability of the human will, yet all the ancients, save Augustine, so differ, waver, or speak confusedly on this subject, that almost nothing certain can be derived from their writings. (Emphasis added.)

The above sentence is pure dynamite. One, Calvin was aware of the early fathers (“all the ancients”) affirmation of free will. Two, that he believed the church fathers spoke “confusedly” meaning there was no patristic consensus on free will. Three, nothing worthwhile can be learned from the early church fathers on this matter. Four, the sole exception among the early church fathers is Augustine.

These are all very interesting theses, but like any set of theses they need to be backed up evidence and arguments. It is disappointing, therefore, to find that Calvin disdains to provide supporting evidence.

Therefore, we shall not stop to list more exactly the opinions of individual writers; but we shall only select at random from one or another, as the explanation of the argument would seem to demand.

My Response to Calvin

If Calvin will not “list more exactly the opinions of individual writers,” then I will. The following citations are presented to show the breadth and depth of the early Church’s affirmation of human free will.

Ignatius of Antioch (d. 98/117), one of the Apostolic Fathers, affirmed human free will:

Seeing, then, all things have an end, and there is set before us life upon our observance [of God’s precepts], but death as the result of disobedience, and every one, according to the choice he makes, shall go to his own place, let us flee from death, and make choice of life. For I remark, that two different characters are found among men — the one true coin, the other spurious. The truly devout man is the right kind of coin, stamped by God Himself. The ungodly man, again, is false coin, unlawful, spurious, counterfeit, wrought not by God, but by the devil. I do not mean to say that there are two different human natures, but that there is one humanity, sometimes belonging to God, and sometimes to the devil. If any one is truly religious, he is a man of God; but if he is irreligious, he is a man of the devil, made such, not by nature, but by his own choice. (Letter to the Magnesians – long version, Chapter 5; ANF Vol. I p. 61; emphasis added.)

The Epistle to Diognetus, considered part of the Apostolic Fathers corpus, affirmed human free will:

. . . as a king sending a son, he sent him as King, he sent him as God, he sent him as Man to men, he was saving and persuading when he sent him, not compelling, for compulsion is not an attribute of God (Epistle to Diognetus 7.3; Loeb Classical Library Vol. II, p. 365; emphasis added).

Clement of Rome (fl. c. 90-100) has been cited in support of free will (see Recognitions 9.30). However, serious concerns have been raised about the authenticity of the Recognitions (Quasten’s Patrology Vol. I, p. 61-62).

Justin Martyr (c. 100-165), an early Apologist who was schooled in classical philosophy before his conversion, wrote:

For the coming into being at first was not in our own power; and in order that we may follow those things which please Him, choosing them by means of the rational faculties He has Himself endowed us with, He both persuades us and leads us to faith (First Apology 10; ANF Vol. I, p. 165; emphasis added).

Athenagoras (2nd century), another early Apologist, wrote:

Just as with men, who have freedom of choice as to both virtue and vice (for you would not either honour the good or punish the bad, unless vice and virtue were in their own power . . . . (Athenagoras’ Plea 24, ANF Vol. II p. 142; emphasis added).

Irenaeus of Lyons (fl. c. 175-c. 195), regarded as the greatest theologian of the second century, likewise affirmed man’s capacity for faith was based in his free will:

Now all such expressions demonstrate that man is in his own power with respect to faith (Against Heresies 4.37.2; ANF Vol. I, p. 520).

Cyprian of Carthage (c. 200/210-258), the spiritual son of Tertullian and one of the Latin Fathers, affirmed human free will. Treatise No. 52 is titled “That the liberty of believing or of not believing is placed in free choice.” (ANF Vol. V p. 547; emphasis added) He gave three Scripture passages in support of this teaching: Deuteronomy 13:19, Isaiah 1:19, and Luke 17:21.

Athanasius the Great (c. 296-373) was renowned for his defense of Christi’s divine nature. In the Life of Anthony §20 he wrote that human virtue depends on the existence of human free will:

Wherefore virtue hath need at our hands of willingness alone, since it is in us and is formed from us (NPNF Vol. IV p. 201).

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-c. 254) in De Principiis Preface §5 made this observation about the general opinion of the Church:

This also is clearly defined in the teaching of the Church, that every rational soul is possessed of free-will and volition; (NPNF Vol. IV p. 240).

Just as significant is the fact that the denial of human free will was rejected as an erroneous teaching. The opposite of free will is “necessity-constrained will,” this Vincent of Lerins (d. before 450) in his Commonitory noted is heretical because it makes sin to be irresistible.

. . . a human nature of such a description, that of its own motion, and by the impulse of its necessity-constrained will, it can do nothing else, can will nothing else, but sin . . . . (Commonitory Chapter 24, NPNF Vol. XI p. 150; emphasis added)

A similar condemnation can be found in Methodius (d. c. 311) in The Banquet of the Ten Virgins:

Now those who decide that man is not possessed of free-will and affirm that he is governed by the unavoidable necessities of fate, and her unwritten commands, are guilty of impiety towards God Himself, making Him out to be the cause and author of human evils (Chapter 16, ANF Vol. VI p. 342; emphasis added).

John Chrysostom (c. 349/354-407), famous for his preaching and patriarch of Constantinople, likewise condemned the denial of human free will in his third homily on Timothy:

Having thus enlarged upon the love of God which, not content with showing mercy to a blasphemer and persecutor, conferred upon him other blessings in abundance, he has guarded against that error of the unbelievers which takes away free will, by adding, “with faith and love which is in Christ Jesus.” (NPNF First Series Vol. XIII p. 418)

Another significant witness to free will is Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 310-386), Patriarch of Jerusalem in the fourth century. In his famous catechetical lectures, Cyril repeatedly affirmed human free-will (Lectures 2.1-2 and 4.18, 21; NPNF Second Series Vol. VII, pp. 8-9, 23-24).

Likewise, Gregory of Nyssa (330-c. 395), in his catechetical lectures, taught:

For He who made man for the participation of His own peculiar good, and incorporated in him the instincts for all that was excellent, in order that his desire might be carried forward by a corresponding movement in each case to its like, would never have deprived him of that most excellent and precious of all goods; I mean the gift implied in being his own master, and having a free will. (The Great Catechism Lecture 5, NPNF Vol. V p. 479)

John of Damascus (c. 675-c. 745), an eighth century Church Father, wrote the closest thing to a systematic theology in the early Church, Exposition of the Catholic Faith. In it he explained that God made man a rational being endowed with free-will and as a result of the Fall man’s free-will was corrupted (Book 3 Chapter 14, NPNF Second Series Vol. IX, p. 58-60).

Saint John of the Ladder (579-649), a seventh century Desert Father, in his spiritual classic, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, wrote:

Of the rational beings created by Him and honoured with the dignity of free-will, some are His friends, others are His true servants, some are worthless, some are completely estranged from God, and others, though feeble creatures, are His opponents (Step 1.1; emphasis added).

A more exhaustive listing can be found in Mako Nagasawa’s “Free Will In Patristics” (August 2013). Interestingly, this paper was written in response to the same passage in Calvin’s Institutes 2.2.4.

A survey of the early Christian writings show the following: (1) the doctrine of human free will was taught by the Apostolic Fathers (Ignatius of Antioch and in the Letter to Diognetus), (2) it was affirmed by the Apologists (Justin Martyr and Athenagoras), (3) it was taught by leading church fathers like Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great, and Gregory the Great, (4) it was taught by Latin Fathers (Cyprian of Carthage), (5) it was taught by Syrian Fathers (John of Damascus), (6) it was taught by the Desert Fathers (John of the Ladder), and (7) it was affirmed by the Patriarch of Jerusalem Cyril in his catechetical lectures. It is inexplicable, not to mention inexcusable, for Calvin to have refused to engage this wide ranging patristic consensus. Calvin in contrast relied almost exclusively on one later church father, Augustine of Hippo. Furthermore, Augustine’s teaching on human free will were written in response to the Pelagian heresy and do not present a balanced position.

Using the Vincentian Canon, Calvin’s denial of human free will cannot be considered part of the catholic faith. Unlike the affirmation of human free will which can be found in the Apostolic Fathers and the Apologists who lived in the second century, Calvin made no appeal to the Ante-Nicene Fathers; thus he fails on the grounds of antiquity. In contrast to Augustine who was a North African bishop, patristic witness to free will can be found across the ancient world: Gaul, Italy, Asia Minor, North Africa, Syria, not to mention the major sees of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. Thus Calvin’s argument also fails on the grounds of ubiquity. At best it can be considered a personal opinion, but not the catholic and universal teaching of the Church.

Not a Fluke

Calvin’s denigration of the church fathers was not an off the cuff or in the heat of the moment hyperbole. Calvin meant what he wrote. As a matter of fact, he repeated this point again in the chapter 2.2.9 (pp. 266-267).

Perhaps I may seem to have brought a great prejudice upon myself when I confess that all ecclesiastical writers, except Augustine, have spoken so ambiguously or variously on this matter that nothing certain can be gained from their writings. . . . . But I meant nothing else than that I wanted simply and sincerely to advise godly folk; for if they were to depend upon those men’s opinions in this matter, they would always flounder in uncertainty. At one time these writers teach that man, despoiled of the powers of free will, takes refuge in grace alone. At another time they provide, or seem to provide, him with his own armor. (Institutes 2.2.9; emphasis added.)

Calvin’s refusal to provide supporting evidence is distressing. What we have here is not scholarship, but dogmatism.

Calvin’s almost exclusive reliance on Augustine of Hippo is alien to the theological method of the early Christians as described in the Vincentian Canon: quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus (What has been believed everywhere, always, and by all.). (Commonitory Chapter 2.6) After citing Origen, Calvin skips over the early Greek fathers to the medieval scholastics: Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033-1109), Peter Lombard (c. 1095-1169), and Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274). Here Calvin is operating as a Western theologian who does theology independently of the patristic consensus.

But some hard questions need to be asked about Calvin’s theological method. First, was Calvin wiser than the host of early Church Fathers? Did the Apostles’ disciples and their successors drop the ball? That is, rather than carefully guard the Apostolic deposit, they carelessly let it be modified to follow their own personal insights or to please their congregations? That right doctrine disappeared and was replaced by heresy? The answer to these questions is: No. History shows that in their wrestling with the issues and questions raised by Greek philosophers and various heresies they sought to be faithful to Holy Tradition. Furthermore, history shows the early Christians willing to die for the Faith rather than to resort to compromise. The more one takes the time to read and learn what the church fathers believed and taught, the more confidence one has that the Holy Spirit did indeed make good on the promise of Christ to teach and lead the Orthodox Church into all truth.

Findings and Conclusions

Institutes 2.2.4 and 2.2.9 provide tremendous insights into Calvin’s theological method. We find that despite his familiarity with the early church fathers and his willingness to cite them Calvin was in fact far removed from the patristic method. He had no interest in learning where the patristic consensus stood on particular issues. For an Orthodox Christian this attitude is alarming.

But even more shocking was Calvin’s airy dismissal of the church fathers on the grounds that their teachings were confused and contradictory. He gives no supporting evidence. Given his reputation as a first rate theologian this is a damning indictment. It suggests not intellectual deficiency but arrogant obstinacy.

If it is true that Calvin’s doctrine of double predestination is at odds with the patristic consensus, then it cannot be considered part of the catholic faith. If that is the case then double predestination is at best a personal opinion or at worst a heresy. The Orthodox Church in the Confession of Dositheus condemned it as “profane and impious” (Decree III, in Leith Creeds of the Churches, p. 488)

It is imperative that modern day Reformed Christians take another look at the early church fathers’ teachings on free will and our salvation in Christ. The classic Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura does not exclude patristic sources. See my review of Keith Mathison’s The Shape of Sola Scriptura. What is needed is for a contemporary Reformed scholar to investigate the church fathers and determine whether or not the Reformed position on double predestination is consistent with the church fathers or whether Calvin was right in asserting that the church fathers were inconsistent and contradictory in their teachings on free will.

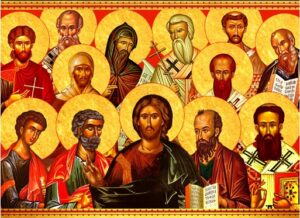

Church Fathers

In closing, I would urge modern day Calvinists to treat the early church fathers with respect and to be open to learning from them. Disrespecting the church fathers is theologically dangerous. It is to risk being alienated from church history, from our spiritual heritage. Not being anchored in the early church fathers put one at risk of either unthinking fundamentalism or syncretistic liberalism.

Robert Arakaki

We see this instability in mainline Protestantism moving further away from its historic roots and the more conservative Protestant groups constantly regrouping and falling back in the face of the constant progressive onslaught. Conservative Protestants find themselves outside the mainline in small continuing Protestant offshoots. This is a logical consequence of the Protestant rejection of Holy Tradition when it embraced sola scriptura. Historic confessions become more like lines drawn in the sand than solid ramparts that withstand the tidal force of change. Stable catholicity requires grounding in Tradition. Doctrinal orthodoxy without catholicity is sectarian.

We see this instability in mainline Protestantism moving further away from its historic roots and the more conservative Protestant groups constantly regrouping and falling back in the face of the constant progressive onslaught. Conservative Protestants find themselves outside the mainline in small continuing Protestant offshoots. This is a logical consequence of the Protestant rejection of Holy Tradition when it embraced sola scriptura. Historic confessions become more like lines drawn in the sand than solid ramparts that withstand the tidal force of change. Stable catholicity requires grounding in Tradition. Doctrinal orthodoxy without catholicity is sectarian. In the face of the Protestant pursuit of progress, conservative Protestantism is nothing more than lines drawn in the sand. The history of Protestantism is littered with confessions, declarations, and statements. As soon as one statement is forgotten and a new situation arises, a new statement is drawn up. This can leave a conservative Protestant weary and disheartened. As a former Protestant who found refuge in the harbor of Orthodoxy, I can say that I found a stable catholicity that has withstood the test of time.

In the face of the Protestant pursuit of progress, conservative Protestantism is nothing more than lines drawn in the sand. The history of Protestantism is littered with confessions, declarations, and statements. As soon as one statement is forgotten and a new situation arises, a new statement is drawn up. This can leave a conservative Protestant weary and disheartened. As a former Protestant who found refuge in the harbor of Orthodoxy, I can say that I found a stable catholicity that has withstood the test of time.

Recent Comments