Prof. Michael Reeves: “Eastern Orthodoxy: An Evangelical Assessment” Source

Protestant conversions to Orthodoxy are attracting the attention of Evangelicals, prompting their leaders to examine it and critique it. Recently, Michael Reeves, President of the Union School of Theology in London, gave a presentation on Orthodoxy. His Evangelical credentials are impressive. He has served as a minister at All Souls Church, Langham Place, in London and has served as Head of Theology for the Universities and Colleges Christian Fellowship. [Source]

Prof. Reeves is to be commended for having read Church Fathers like Athanasius the Great, Gregory Palamas, Dionysius the Areopagite (aka Pseudo-Dionysius), as well as researching the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea II, 787). Some may find Prof. Reeves’ meticulous analysis pedantic and difficult to listen to. Others may dismiss Reeves on the ground he misrepresents Orthodoxy. Patience and humility are essential for maintaining Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. We are living in an unusual period of church history. Only a few years ago, conversations between Evangelicals and Orthodox were almost unheard of. At present we have an opportunity for the two traditions to learn from each other.

If I have a complaint about Prof. Reeves’ presentation, it would be that he could have been forthright about his theological bias. His critique of Orthodoxy is not objective, but one shaped by a particular theological tradition—the Western, Augustinian tradition. His bias appears throughout his lecture, e.g., his favoring the Augustinian understanding of God’s incomprehensibility (22:06-23:54), his complaint that Orthodoxy has a weak view of the Fall along with the absence of the idea of total depravity (41:24-30), and his rejection of synergism (45:11). Where Western Christianity, Roman Catholicism and Protestantism, rely almost exclusively on Augustine of Hippo, Orthodoxy draws on a much wider range of Church Fathers.

Why Orthodoxy Appeals to Evangelicals

Reeves notes that Evangelicals are drawn to Orthodoxy’s mysticism (1:14), its rootedness (2:12), or its mystical beauty (2:29). He sees Orthodoxy’s obscurity as another reason for its appeal. At the 2:41 mark, Prof. Reeves observes:

And also, somewhat more humdrum perhaps, I think some of the converts you see from Evangelicalism to Eastern Orthodoxy are fleeing particular Western problems to an unknown that can be molded. So Roman Catholicism is more of a known quantity, Eastern Orthodoxy is a slightly more less defined and slightly less known quantity. And therefore you can flee it into a religion that can be more comfortable according to what you want (2:41-3:18; emphasis added).

I was amused when I heard Prof. Reeves’ description of Orthodoxy as a “comfortable religion.” Orthodoxy’s ascetic disciplines such as the weekly Wednesday and Friday fasts, the annual forty-day Lenten fast, and the requirement of going to confession, make Orthodoxy much more demanding than Evangelicalism. Furthermore, his characterization of Orthodoxy as “an unknown that can be molded” is simply ridiculous. Inquirers into Orthodoxy (catechumens) will soon learn about Orthodoxy’s ascetic disciplines, its dogmas, its rejection of heresies, its way of worship, and the authority of bishops.

It should be noted that there is one more reason that Orthodoxy appeals to Evangelicals: doctrine. Orthodoxy’s doctrinal stability offers relief to Evangelicals weary of trendy fads, or to those troubled by the many conflicting denominational doctrines, the abandonment of traditional Christian morality, and theological liberalism.

The Two Strands of Orthodoxy

For his presentation, Prof. Reeves selected two main talking points—or what he calls “core doctrinal points”—to Orthodox theology: icons and apophatic theology.

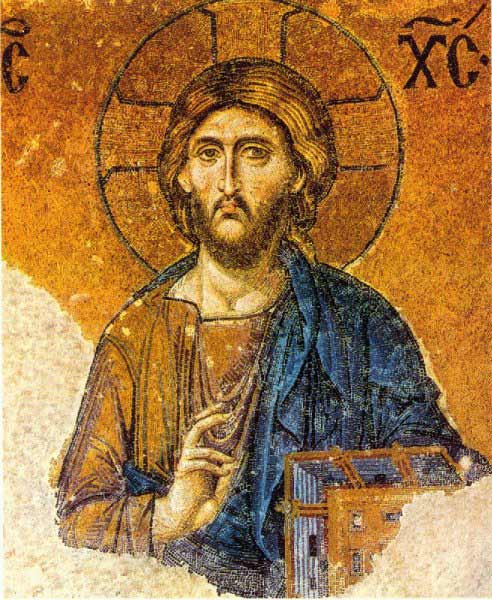

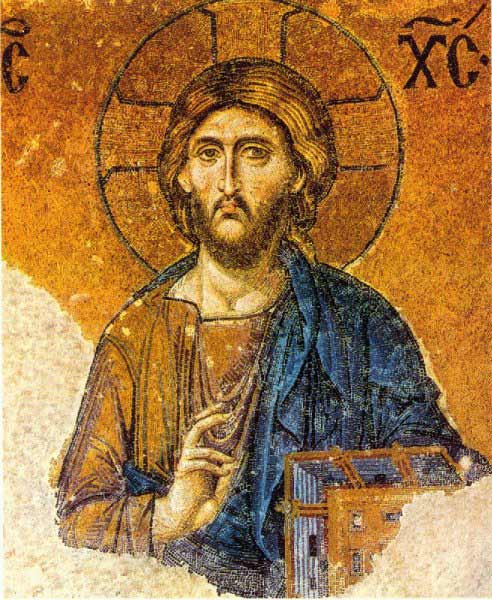

Pantocrator Icon – Hagia Sophia

Icons

It is quite understandable that Reeves selected icons for assessing Orthodoxy. Icons represent the most visible difference between the two traditions. Reeves is under the impression that icons are central to Orthodox identity (6:57). While icons are very much a part of Orthodoxy, even more central to Orthodox identity is the Eucharist. Orthodoxy believes that in the Eucharist we truly receive Christ’s body and blood, and that it is through the Eucharist that we are united to Christ and the Church. Thus, the Eucharist is more suitable for helping Evangelicals understand Orthodoxy and its approach to icons. If one accepts the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist, one can then grasp the sacramental nature of icons—how icons are truly windows to heaven. The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is based on the Incarnation—the Word becoming flesh for our salvation. The Incarnation teaches embodied grace, that God’s grace can be conveyed through material substance such as water, wine, bread, oil, incense, and physical gestures like the sign of the Cross, etc. This is quite different from Evangelicalism, which emphasizes God’s grace conveyed through words—the Bible and the sermon.

In his presentation on icons, Michael Reeves examines John of Damascus, then Gregory Palamas. He describes John of Damascus’ argument that the Incarnation provides the basis for the veneration of icons (9:10-11:20). Reeves then notes that the Orthodox theology of icons reaches its full development with Gregory Palamas’ teaching on Christ’s transfiguration on Mount Tabor (11:30-17:30). The Transfiguration of Christ, in which His visible, picturable human flesh emanated the divine glory, implies that physical matter like wood and paint can also transmit the divine glory (16:49).

I was surprised at the attention Reeves gives to Gregory Palamas. Gregory Palamas is more usually associated with the fourteenth century hesychasm (inner silence) controversy, not the eighth century iconoclasm controversy. While Gregory’s writings on the uncreated energies could certainly be used to defend the veneration of icons, Orthodoxy for the most part has not made much use of Gregory Palamas to defend icons. I found an excerpt of Gregory Palamas’ teaching on icon and was struck by his reserved understanding of icons, which was in keeping with the general Orthodox approach to icons.

You must not, then, deify the icons of Christ and of the saints, but through them you should venerate Him who originally created us in His own image, and who subsequently consented in His ineffable compassion to assume the human image and to be circumscribed by it. [Source]

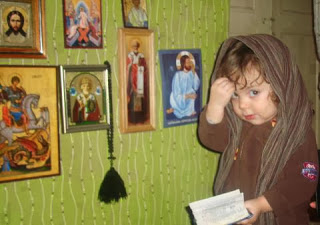

A child venerating icons. Soruce

It would be helpful if Prof. Reeves were to provide us with excerpts from Gregory Palamas that support his position.

Reeves makes the point that the Palamite teaching on the uncreated light leads to Orthodox Christians gazing at icons in order to experience the divine glory.

You can spend time gazing upon an icon, Mary, or Gregory Palamas through that. What you’re wanting to see is to see the uncreated light of God’s glory. That’s what you’re wanting to experience. (17:15-31)

Here Michael Reeves completely misunderstands and thus misrepresents how Orthodox Christians relate to icons. Orthodox Christians are encouraged to have icon corners, where they spend time in prayer before the icon of Christ and the saints, but they are not encouraged to gaze at icons. Basically, we pray to the person depicted in icons. Likewise, icons are not the focal point in the Liturgy. Attention rather is given to the prayers, the hymns, the Scripture readings, and to the Eucharist. We do not fixate on icons; that’s not healthy Orthodox spirituality. Reeves’ misunderstanding of Orthodoxy here apparently stems from his limited exposure to lived Orthodoxy.

Apophatic Theology

Where Western Christianity favors cataphatic theology—theology through words and thoughts, Orthodoxy favors apophatic theology—theology without words. Prof. Reeves contrasts the Western Augustinian approach to knowledge of God against the Eastern apophatic approach (22:06 ff.). Paraphrasing Pseudo-Dionysius, Reeves describes apophatic theology:

God is literally above essence. He is super essential. Now, what’s that going to do to your knowledge of God? If that’s your way you do theology? Having fenced off what God is not, you haven’t yet said what He is. And so what God is has not been defined. God is left in this theology, ultimately in the darkness of unknowing. (27:35-28:07)

Michael Reeves fails to take into account that in Orthodoxy the individualized monastic prayer of hesychasm is complemented by the corporate prayer in the Liturgy. In the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, we find cataphatic theology complementing apophatic theology:

It is proper and right to hymn You, to bless You, to praise You, to give thanks to You, and to worship You in every place of Your dominion. For You, O God, are ineffable, inconceivable, invisible, incomprehensible, existing forever, forever the same, You and Your only-begotten Son and Your Holy Spirit. You brought us out of nothing into being, and when we had fallen away, You raised us up again. You left nothing undone until you had led us up to heaven and granted us Your Kingdom, which is to come. For all these things, we thank You and Your only-begotten Son and Your Holy Spirit: for all things we know and do not know, for blessings manifest and hidden that have been bestowed on us. (Emphasis added)

Here in the Anaphora (prayer of consecration) the Orthodox priest declares God’s unknowableness while also confessing God as Trinity working to save fallen humanity. [Video of the Anaphora at 1:35] Orthodoxy affirms both theology with words and theology without words. Where we part ways with Western Christians is with respect to the adequacy of theology with words. Western Christianity abounds with books on systematic theology and detailed statement of faiths. This is largely absent in Orthodoxy, which places greater emphasis on prayer. That is why the climax of Orthodox worship is not the sermon but the Eucharist.

Michael Reeves is concerned that apophatic theology creates a “super idol” that leaves us in the “darkness of unknowing.” (27:11) He suggests that Orthodoxy’s apophaticism has a problem similar to the Arian heresy: the lack of true knowledge of God. The Arian position that the Son is not God implies then we do not have a genuine revelation of God. In a similar way according to Reeves, the problem with Orthodoxy’s apophaticism is that if God is unknowable then even with the Incarnation we will end up without a genuine knowledge of God. However, Reeve’s position is not without the same problem as well. In his presentation on Gregory Palamas, Reeves failed to mention the historical context, that is, Palamas’ controversy with Barlaam of Seminara. Gregory Palamas developed his understanding of the uncreated light of Tabor in response to Barlaam’s disavowal that direct knowledge of God could be possible. In rejecting Gregory Palamas, Reeves seems to be taking the Barlaamite position that at best we can have knowledge about God, but we cannot have direct knowledge of God.

When Prof. Reeves selected apophatic theology for his presentation, I was both surprised and not surprised. I was not surprised, as early on I had encountered books and essays about Orthodoxy’s apophatic approach to knowing God. Yet, I was surprised because little mention is made of apophatic theology in the everyday life of Orthodox Christians. On a daily basis, Orthodox Christians are more concerned with following a prayer rule than with constructing theological systems. Prof. Reeves misunderstands the role of apophaticism in Orthodox life.

The theology of the Orthodox Church is found primarily in its worship—the Divine Liturgy. In Orthodoxy, theology is not so much written down as it is sung and prayed. Orthodox worship consists of the Sunday Liturgy, Sunday morning Matins, Saturday evening Vespers, the occasional Memorial services, as well as the Holy Week services that culminate in the glorious Pascha (Easter) Service. As an intellectual, I am nourished by the prayers and services of the Church. I have found that the spiritual realities discussed in theological works can be apprehended through the cultivation of prayer and the denying of the flesh. Without these spiritual disciplines, all one has is head knowledge, and head knowledge detached from prayer is dead knowledge. True theological knowledge is life-giving. True theology transforms the soul and leads to deification. Evagrius Ponticus, a fourth century desert father, once wrote:

If you are a theologian, you will pray truly. And if you pray truly, you are a theologian.

Apophatic theology is difficult for the average Christian to grasp. My advice to Evangelical inquirers is not to worry about understanding this doctrine. Rather, using your personal faith in Christ as a starting point, ask whether Orthodoxy can help deepen your spiritual life. Attend the Orthodox Sunday services (liturgy), listen to the prayers and hymns, incorporate Orthodox prayers into your daily devotions, and determine whether Orthodoxy has a deepening effect on your relationship with God who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Deification

One criticism Prof. Reeves makes of the Orthodox doctrine of deification is that it has changed over time, especially under Gregory Palamas (17:52-21:02). To explain the doctrine of deification, many Orthodox Christians make reference to Athanasius’ statement that the Son of God became man so that men might become sons of God (On the Incarnation §54; NPNF Vol. IV p. 65). Orthodoxy understands salvation in Christ as involving a transformation much like a sword when thrust into a fire takes on the properties of the fire, becoming hot and glowing, while still remaining a sword. According to Reeves, the Incarnation involves Christ bringing to humanity his knowledge of the Father (18:49). By sharing his knowledge of the Father, Christ brings us into a relationship with his Father, something that we might today call adoption (19:06; 19:20). This relational knowledge of the Father results in our transformation and glorification. Reeves defines deification as “sharing in the divine communion” (19:30) but he seems to shy away from the more ontological understanding of deification as presented in 2 Peter 1:4: “become partakers of the divine nature.” (RSV) Reeves’ unwillingness to address the ontological aspect of deification in this biblical passage strikes me as rather puzzling.

Reeves argues that with Palamas deification shifts from relational knowledge of God to being filled with the uncreated light. The logical result is that deification is no longer a “relational ideal.” (20:10-15). He goes on to note that here deification is no longer relational but more like “receiving the force of divine glory” (20:29). I take issue with Reeves’ claim that deification under Palamas is receiving an impersonal force. At the heart of the hesychast controversy was the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” This is not a mantra, but a prayer—a person-to-person dialogue. The Orthodox Church encourages her members to say the Jesus Prayer. It is believed that through continuous prayer the Christian will unite himself or herself with Christ and in the process will be transformed into Christ’s likeness (deification).

Reeves makes the argument that Gregory Palamas’ understanding of deification diverged from that of the early Church Fathers such as Irenaeus and Athanasius. For the Orthodox, this is a serious charge in light of Orthodoxy’s insistence that the essential elements of its theology remain unchanged. I would need to hear more from Prof. Reeves on how he reached that conclusion. Reeves warns against reading modern Eastern Orthodox understanding of deification into the early Church Fathers, because they are not exactly the same (21:02). My guess is that it is Prof. Reeves himself who is reading Athanasius with Western Augustinian lenses. This would explain the divergence he sees between Athanasius and Gregory Palamas. It should be kept in mind that Athanasius’ organic understanding of the Incarnation and deification is integral to Orthodox soteriology, but lies on the margins of Western Augustinian/Calvinist forensics-based soteriology.

Theological Faux Pas

Reeves asserts that Gregory Palamas’ energies/essence distinction implies that there are two parts to God. (33:53) This is sheer nonsense and no Orthodox Christian would agree to this. I winced when Prof. Reeves seeks to refute Gregory Palamas by asserting that it was not the energies of God that was Incarnate but the essence of God (34:59). I winced because in good Trinitarian theology it was the second Person of the Trinity, the Son, who is of the same essence as the Father, who became Incarnate. Whenever any competent theologian discusses the Trinity, they need to handle the terms Essence, Persons, and Energies competently or else there will be confusion and misunderstanding.

Lord Have Mercy!

Michael Reeves cites Gordon-Conwell professor Donald Fairbairn’s observation that the Orthodox practice of repeatedly saying “Lord, have mercy!” in their services has a weakening effect on their relationship with God. To Fairbairn this suggests a lack of confidence in God’s mercy in light of God being unknowable (35:47). My first response is to ask: Is this based upon your interviews with Orthodox Christians? How large and representative was your sample population? My next response is that it is because we are confident in God’s love that Orthodoxy delights in saying: “Lord, have mercy!” We are constantly reminded of God’s love for us throughout the Liturgy all the way up to the closing prayer: “for He is good and loves mankind.” In the Reformed tradition, this confidence is shadowed by the doctrine of double predestination—God will have mercy on the elect, but not on the damned. While Calvinists cannot ask for God’s full mercy on all men—since by his supposed eternal decree, God has damned all non-elect to eternal hell and torment—the Orthodox call upon God’s mercy in intimate and cherished confidence knowing that God is a loving God abounding mercy to all. My advice to Evangelical inquirers is that they meet with Orthodox believers and ask them their understanding of the liturgical response—“Lord, have mercy!”—and how it shapes their understanding of God.

Two Acts Versus Three Acts of Salvation?

Prof. Reeves describes the Orthodox view of salvation as having a two-act schema: Creation, then Deification (43:11), versus the Western three-act schema: Creation, Fall, and Redemption (42:40-42:56). According to Reeves, in the Orthodox two-act schema not much is made of the Fall in the middle. It is there but it’s not such a prominent feature (43:19). This is a gross misrepresentation of the Orthodox Church’s understanding of salvation. The three-act schema can be found in the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom. An examination of the Anaphora, the prayers said for the consecration of the bread and wine, shows the three acts numbered in brackets: 1 – Creation, 2 – Fall, and 3 – Redemption:

[1] You brought us out of nothing into being, and [2] when we had fallen away, [3] You raised us up again. You left nothing undone until you had led us up to heaven and granted us Your Kingdom, which is to come.

A more detailed three-act schema can be found in the Anaphora of Saint Basil’s Liturgy, which the Orthodox Church uses ten times a year.

You have ordered all things for us. [1] For having made man by taking dust from the earth, and having honored him with Your own image, O God, You placed him in a garden of delight, promising him eternal life and the enjoyment of everlasting blessings in the observance of Your commandments. [2] But when he disobeyed You, the true God who had created him, and was led astray by the deception of the serpent becoming subject to death through his own transgressions, You, O God, in Your righteous judgment, expelled him from paradise into this world, returning him to the earth from which he was taken, yet providing for him the salvation of regeneration in Your Christ. For You did not forever reject Your creature whom You made, O Good One, nor did You forget the work of Your hands, but because of Your tender compassion, [3] You visited him in various ways: You sent forth prophets; You performed mighty works by Your saints who in every generation have pleased You. You spoke to us by the mouth of Your servants the prophets, announcing to us the salvation which was to come; You gave us the law to help us; You appointed angels as guardians. And when the fullness of time had come, You spoke to us through Your Son Himself, through whom You created the ages.

[2] For, since through man sin came into the world and through sin death, it pleased Your only begotten Son, who is in Your bosom, God and Father, born of a woman, the holy Theotokos and ever virgin Mary; born under the law, to condemn sin in His flesh, [3] so that those who died in Adam may be brought to life in Him, Your Christ.

Here we see one of the basic differences between Evangelicalism and Orthodoxy. Where Protestant theology is principally scholastic theology, Orthodox theology is basically liturgical theology. This goes back to the ancient theological principle: lex orandi, lex credendi (the rule of prayer is the rule of faith). In focusing on written texts to the exclusion of the Liturgy, Prof. Reeves ended up misapprehending and misrepresenting Orthodoxy. This focus on written texts is understandable in light of the influence of Roman Catholic Scholasticism on Protestantism. Without his knowing it, the Western theological tradition has biased Prof. Reeves’ assessment of Orthodoxy. Orthodoxy is not Western. Hence, it would not be appropriate to expect Orthodoxy to conform to the parameters of the Western Augustinian tradition.

My Assessment and Advice

Throughout his presentation, Prof. Michael Reeves maintained a positive tone towards Orthodoxy. In his assessment, Reeves did not pull his punches. He points to what he sees are its logical inconsistencies, its divergence from the patristic position, its susceptibility to certain heresies, and its divergence from “authentic” (Augustinian) Christianity. Overall, I found a certain abstract quality to Prof. Reeves’ assessment of Orthodoxy. My impression is that he read with care a number of Orthodox texts, analyzed them in terms of theological systems, and assessed them for logical consistency and conformity to Augustine/Calvin. I do not have the sense that Prof. Reeves had attended Orthodox services or that he had spent time talking with Orthodox Christians. Orthodoxy is not a theological system as it is a way of life.

My advice to Protestants curious about Orthodoxy is that they take notes from Prof. Reeves’ presentation, visit an Orthodox church, and use the notes to ask questions about Orthodoxy. Attend the Sunday Liturgy (preferably an all-English service) and listen to the prayers and hymns. Seek out former Protestants who have converted to Orthodoxy. These converts can serve as translators explaining the similarities and differences between Orthodox and Protestants terms. Ask how Orthodoxy has shaped their understanding of God, how they pray, and how they approach life. See for yourself if there is merit to Prof. Reeves’ assessment of Orthodoxy. It is also important that curious Evangelicals meet with an Orthodox priest, preferably one who is a convert. While there are many well-read converts, it is the priest who speaks with the authority of the Church. I close with a friendly, brotherly challenge to Prof. Reeves and other curious Evangelicals in the form of a biblical quotation from John 1:46. Philip in response to Nathaniel’s skepticism replies: “Come and see!”

Robert Arakaki

References and Recommended Readings

Michael Reeves. “Eastern Orthodoxy: An Evangelical Assessment—Michael Reeves.” Forum of Christian Leaders Online [45:59] 19 November 2018.

Bishop Alexander – Bulgarian Diocese OCA. “Force Your MInd to Descend into the Heart.” Voices from St. Vladimir’s Seminary – Ancient Faith Radio. 17 September 2014.

All Saints Orthodox Church – Linconshire, Lincoln. “The Anaphora of St. John Chrysostom.” [14:19 @ 1:35]

Athanasius the Great. On the Incarnation. New Advent and NPNF.

Rod Dreher. “Meditation & The Jesus Prayer.” The American Conservative. 15 July 2014.

Donald Fairbairn. Orthodoxy through Western Eyes. [Mentioned by Reeves at 35:47]

Stephen Freeman. “Apophaticism.” Glory to God for All Things. 9 December 2008.

Stephen Freeman. “Belief and Practice.” Glory to God for All Things. 26 June 2009.

Michael Harper. A Faith Fulfilled. [Mentioned by Reeves at 1:14]

“Hieromartyr Irenaeus the Bishop of Lyons.” Orthodox Church in America.

John of Damascus. “#202: John of Damascus for Icons.” Christian History Institute.

Anna Keating. “Why Evangelical megachurches are embracing (some) Catholic traditions.” America. 5 May 2019.

Catherine Mowry LaCugna. God for Us: The Trinity & Christian Life. HarperSanFrancisco.

Robert Letham. Through Western Eyes: Orthodoxy: A Reformed Perspective. [Mentioned by Reeves at 32:55]

Vladimir Lossky. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church.

George Maloney. A Theology of “Uncreated Energies.”

“St Gregory Palamas on Holy Icons.” A Reader’s Guide to Orthodox Icons.

“St. Gregory Palamas the Archbishop of Thessalonica.” Orthodox Church in America.

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware. “Hesychasm in the Orthodox Christian Tradition.” St. Andrew Greek Orthodox Church.

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware. “Jesus Prayer – Breathing Exercises.” OrthodoxPrayer.org

Recent Comments