A Response to David Roxas (2 of 4) (1 of 4)

Can Christianity Exist Apart From Oral Tradition?

David Roxas asked:

1. Absent a body of oral tradition and the corpus of the church Fathers, which both developed over centuries and which the Fathers themselves did not have (Irenaus [sic] was not reading the Cappadocian Fathers nor was he celebrating the liturgy of Chrysostom) what is the source of Christian knowledge of God, the law, and the Gospel of Jesus Christ? From whence did the later developed corpus of the Fathers and the oral tradition receive it’s knowledge of the Gospel? (Emphasis added.)

Answer: To assume the absence of an identifiable Tradition for the first hundreds of years – that the Church Fathers presumably had no access to – betrays a woeful ignorance of Scripture and church history. In light of what the Apostle Paul wrote to Timothy about safeguarding the deposit of oral Tradition (see my prior article), it is impossible for the Church to have existed apart from oral Tradition. As a matter of fact, it is contrary to Scripture! The issue is not whether there was an oral Apostolic Tradition. Rather, the question should be: What evidence is there of oral Apostolic Tradition closer to the time of the Apostles than a fourth century witness like Basil the Great?

One important source is the Didache which dates to A.D. 100. We learn from the Didache: (1) the threefold baptism (7.1), (2) only the baptized may be allowed to partake of the Eucharist (9.5), and (3) Christians were expected to keep the Wednesday/Friday fasts (8.1).

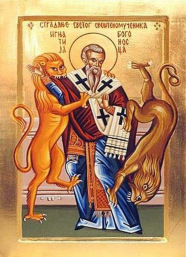

Another important witness to oral Tradition is Ignatius, the third bishop of Antioch, whose death has been dated to either A.D. 98/117. From Ignatius we learn: (1) a baptism or celebration of the Lord’s Supper needed the bishop’s approval to be valid (Smyrnaeans 8.2), (2) the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Lord’s Supper (Smyrnaeans 7.1), and (3) the threefold order of bishop, presbyters, and deacons (To Polycarp 6.1). It is important to keep in mind that Ignatius was bishop over Antioch, Apostle Paul’s home church! (Acts 13:1-3) Ignatius’ connection to the New Testament can be seen in the tradition that he was the child on Jesus’ lap when he said: “Let the children come to me.” (Matthew 19:14-15)

Then there is Justin Martyr (c. 100-165) who in his First Apology (Chapters 65-67) described early second century worship as taking place on Sunday instead of the Jewish Sabbath (Ch. 67), being liturgical (see “the prayers” in Ch. 65), and affirming the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist (Ch. 66).

. . . so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh. (First Apology Ch. 66)

What we have here is oral tradition that describe the application of New Testament teachings. What we do not see here is biblical exegesis like that favored by Protestants. The Didache, Ignatius’ letters, and Justin’s apologia all touch upon practices which are quite unfamiliar to modern day Protestants but familiar to Orthodox Christians. For example, as a Protestant I did not know of the Wednesday/Friday fasts observed by Orthodox Christians. After I learned about the Orthodox fasts, I was pleasantly surprised to find Orthodoxy’s ascetic disciplines supported by the first century Didache. So likewise, I was pleasantly surprised that Irenaeus’ belief in the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Eucharist (Against Heresies 4.18.5; ANF p. 486) agreed with that of Ignatius of Antioch.

Father John Whiteford – a former Protestant, now an Orthodox priest – describes how reading Ignatius made a profound impact on his theology.

I also began reading the Fathers themselves, not just reading about them, with the occasional quotation one might encounter. Coming from Protestant assumptions, the earlier the Father was, the more trustworthy he was likely to be. One of the earliest Fathers to be found outside of the New Testament is St. Ignatius of Antioch. He was a disciple of the Apostle John, was consecrated Bishop of Antioch by St. John himself, and martyred in the arena of Rome in 112 A.D. So I read his seven epistles with great interest, and was again and again struck by the fact that he was not a protestant [sic]. (Source)

Another important early witness to the Scripture-in-Tradition paradigm is the early Latin apologist Tertullian (c. 155-c. 240). In De Corona, chapter 3, Tertullian describes some of the Christian practices not mentioned in Scripture, e.g., triple immersion baptism, receiving Holy Communion from the hands of the priest, memorial services for the dead, and making the sign of the Cross. Apparently back then, there were some who insisted in a very Protestant manner that there be biblical justification for these Christian practices. Tertullian refutes them by posing the question:

For how can anything come into use, if it has not first been handed down? Even in pleading tradition, written authority, you say, must be demanded. Let us inquire, therefore, whether tradition, unless it be written, should be admitted. Certainly we shall say that it ought not to be admitted, if no cases of other practices which, without any written instrument, we maintain on the ground of tradition alone, and the countenance thereafter of custom affords us any precedent. (De Corona Ch. 3, ANF p. 94; emphasis added)

Here Tertullian admits outright that there is no explicit biblical warrant for these practices because these are grounded in unwritten Tradition. For Tertullian the lack of biblical proofs is no obstacle for following these customs.

If, for these and other such rules, you insist upon having positive Scripture injunction, you will find none. Tradition will be held forth to you as the originator of them, custom, as their strengthener, and faith as their observer. That reason will support tradition, and custom, and faith, you will either yourself perceive, or learn from some one who has. (De Corona Ch. IV, ANF p. 95; emphasis added)

Where Irenaeus refutes sola scriptura implicitly, Tertullian refutes it explicitly on the grounds that Christianity follows tradition along with Scripture. It would not be until the idea of oral Apostolic Tradition came under direct attack in the fourth century that Basil the Great (330-379) felt obliged to list them in his classic On the Holy Spirit (see Ch. 27 §66).

To sum up, oral Apostolic Tradition does not comprise a corpus parallel to Scripture. Rather, early Christianity comprised a totality: Scripture, a received way of worship, a received moral code, a received set of spiritual disciplines, and a received church structure. All these informed the early Church’s understanding of Scripture. This ancient Christian way of doing things continues on today in Orthodoxy.

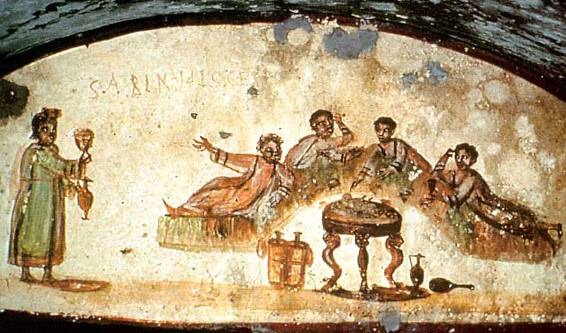

As a religion, Orthodoxy is centered around the Liturgy and the Eucharist. A strong similarity can be seen between Orthodoxy and first-century Judaism which likewise was almost entirely centered around the sacrificial worship of the temple in Jerusalem. The text-centered religion that Protestants favor would be alien to the first century Judaism, Jesus and Paul were acquainted with. Protestantism’s text-centered religion more strongly resembles rabbinical Judaism which emerged in the wake of the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70. Where Orthodoxy represents a continuation of the Judaism of the Bible, Protestantism is rooted in post-biblical rabbinical Judaism. See Gabe Martini’s article: “The Temple Cult and Early Christian Worship.”

Is the Biblical Canon Holy Spirit Inspired?

Many Protestants who assert sola scriptura are unaware of the multiple debts they owe to the early Christians. One debt is the physical Bible. The clergy of the early Church were responsible for the preservation of the physical copies of the Bible. During the early persecutions, the Roman authorities knew that to destroy Christianity they needed to destroy the copies of the Bible. Early Christian clergy hid the sacred Scriptures during the week and brought them to the liturgical gatherings on Sunday. For a cleric in the early Church to hand over Scripture to Roman authorities was a grave sin. The early Christians also faced the challenge of discerning which writings were to be read as Scripture during the Sunday worship and which writings were to be left out. This spurred the making of a list of writings recognized as divinely inspired and authoritative Scriptures which would in the biblical canon we have today.

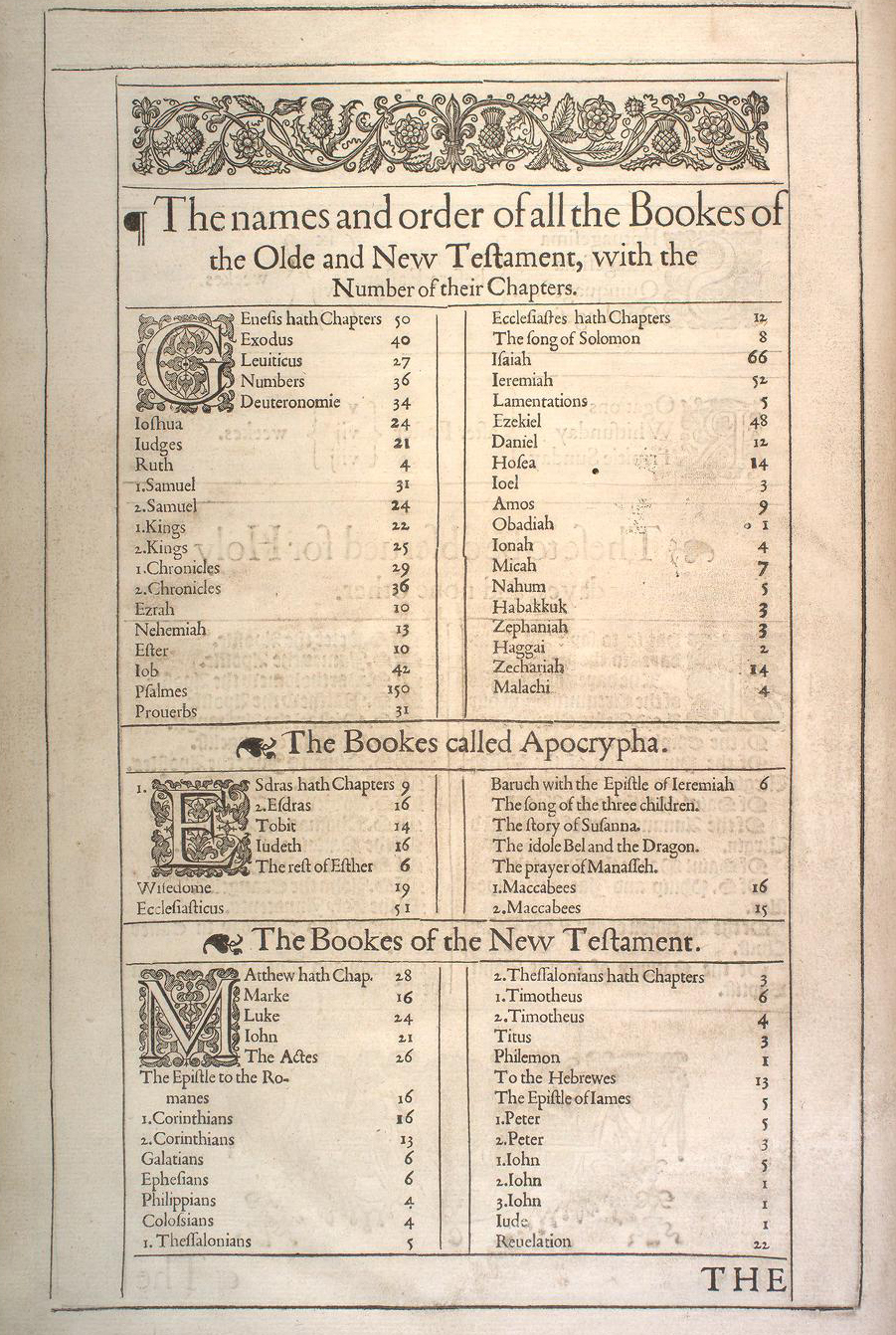

Another debt Protestants owe the early Church is the biblical canon. Many Protestants stress that the writings of the New Testament were all written by the end of the first century, but what they fail to note is that there were many other writings (including some so-called Gospels) that were in circulation at the same time. Thus, one of the challenges facing the early Church was discerning which writings were apostolic and which were not. Irenaeus of Lyons faced this challenge when the Gnostics circulated their heretical version of the Gospel. To combat this Irenaeus fell back on oral Tradition to discern right doctrine. He writes:

For if what they [the Gnostics] have published is the Gospel of truth, and yet is totally unlike those which have been handed down to us from the apostles, any who please may learn, as is shown from the Scriptures themselves, that that which has been handed down from the apostles can no longer be reckoned the Gospel of truth. (Against Heresies 3.11.9; ANF p. 429; emphasis added)

At this early period when there was no definitive listing of apostolic writings (canon) — no Bible book with a table of contents in the front. Irenaeus fell back on what he had received from his predecessor, Polycarp, the disciple of Apostle John. Because the “Gospel” the Gnostics propagated was unlike anything he had received, Irenaeus was obliged to reject them outright. Here we see how the biblical canon emerged out of a traditioning process.

By the end of the second century, a consensus emerged around the four Gospels and Paul’s letters, but it took much longer for a consensus to be formed around Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, the letters by John, and Revelation. A consensus emerged gradually with respect to the exclusion of the Shepherd of Hermas and 1 and 2 Clement from the New Testament. It was not until the late fourth century that the biblical canon was formally closed by the Church. Athanasius’ listing dates to A.D. 367 about the same time as the Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great, and between the First Ecumenical Council (Nicea I in A.D. 325) and the Second Ecumenical Council (Constantinople I in A.D. 381). In the Latin West, similar lists were disseminated by Augustine of Hippo (On Christian Doctrine, Chapter 8 §12-13) and Saint Jerome (Prologue to the Book of Kings).

With respect to the biblical canon, Protestants must ask themselves whether the early Church was guided by the Holy Spirit in the determination of the biblical canon? Or was the biblical canon the result of church politics? A divinely inspired Bible requires a divinely inspired listing (canon) but then this assumes that there was a spiritually vibrant Church led by the Holy Spirit in the first four centuries. The Church of the fourth century that finalized the biblical canon is the same Church that held the First and Second Ecumenical Councils that formulated the Nicene Creed. The fourth century was also a time when Church Fathers like Athanasius had to defend the Gospel against the heresy of Arianism. The fourth century was also the time of great Church Fathers like Athanasius the Great, Ambrose of Milan, John Cassian, Basil the Great, John Chrysostom, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus. Can we not say that the Church Fathers were guided by the Holy Spirit in defending the Faith against heresies? Protestants may want to ignore or even deny that there was a vibrant Holy Spirit inspired Church during the first four centuries, but if we assume a compromised Church riddled with heresies then how can we have confidence in the biblical canon? Such an understanding of the early Church does not reflect the historical evidence, nor does it respect Christ’s promise of a continuing Pentecost in the Church.

Robert Arakaki

In speaking about Tradition, it’s always worth noting how Protestants forget that they have their own tradition, which can only be traced back to the Reformers, making the gross assumption that the beliefs and practices of the Reformers were one and the same thing as those traditioned by the Holy Apostles to the Orthodox Bishops. As a side note, I usually refer to this gross assumption made by today’s Protestants as the “Matzah-Crackers-and-Grape-Juice theology” [depending on which theologization one may want to follow; e.g., Cavinism vs. Lutheranism vs. Zwinglianism vs. Restorationism.

Moreover, I’ve always been amused at how Protestants accuse the Orthodox of following “man-made traditions” when it’s actually Protestantism that is itself almost entirely man-made. It is man-made in the obvious sense that it is undoubtedly the direct bi-product of medieval Catholicism’s scholastic rationalizations, of which the Reformers were heirs and now the supreme pontiffs and infallible heads of their own newly proclaimed Christian cacodoxies reformed after their own image and likeness; nonetheless, in exact mirror opposition to the Papal Church they hated so much. Most woefully, Protestantism’s traditions end up being self-centered in so far as they are no less profoundly non-Apostolic than the “Me-My-Jesus-and-My-Bible” gnostic religiosity into which they unwittingly continue to [d]evolve – but I respectfully digress.

Hi Robert,

The sparcity of evidence in the 2nd century means there is a lack of evidence not a lack of Tradition. While there is some evidence it does leave room for Protestant doubters.

Yes, a continuing Pentecost of the Holy Spirit’s presence in the early Church is a far

bigger Protestant problem than most are willing to grant. IF…the the Church quickly

fell after the Apostles died into a corrupting Apostasy — what Church was it that put

the NT Scriptures together, answered & refuted the the Heretics, laid down our Trinitarian

and Christological doctrines…and wrote the early Creeds of the Church we still use.

The falling away Apostate early Church dies the death of a thousand qualification, which

means it’s a convenient myth — it never happen. Church history is decidedly contra-

Protestant — & overwhelmingly Pro-Orthodox.

Here is the problem with “evidence” on both sides: to mean anything facts have to he selected, prioritized and put into context. Thus “evidence” cited by both sides is routinely thrown out as either inconsequential or meaningless by the other side.

Nor is it a matter of trying to find the most common denominator because even an agreement on Jesus Christ as Savior can become problematic if one looks at the actual Christology. That is why the Fathers of the Church fought so hard over who Christ is.

Jesus’ question to Peter remains crucial. “Who do you say I am?”

Everyone knows the words Peter said but even such a clear statement of belief does not seem to settle it. Let alone Jesus proclamation after Peter’s confession.

The actual lives of the saints before and after their repose would seem to settle the matter of their holiness and their worthiness to be honored, but that is not accepted as evidence by many. One does not have to go back hundreds of years to saints in the far past. There are a number of Orthodox saints who labored in this country in the twentieth century. Most notible:. St. John, Wonderworker of Shanghi and San Francisco whose largly incorrupt remains lie in state in the Joy of All Who Sorrow Cathedral in San Francisco . He reposed in 1966 and was widely recognized as a saint by many before his repose. But the testimony of his life and miracles does little to sway modern people. Why is that I wonder?

When we Orthodox question the completeness of the three “alones” we often come under suspicion as doubting the salvific nature of the Bible, Divine Grace and even Jesus Himself. That is wholly untrue. We just have the rest of the story.

It is a matter of the heart, the whole mind, not just the rational part. It is a matter of actually encountering the living God in the person of Jesus Christ, not just believing in Him in some kind of formulaic way — Protestant or Orthodox.

That encounter is unique for everyone because salvation is deeply personal (not individual). There are many components that can be described and a certain commonality to them but they are never identical

Keep in mind, salvation for we Othordox is simple: union with Jesus Christ by His grace and mercy. That union seems to have a conjugal quality to it because He took on our full nature, taking flesh from Mary, the Theotokos and becoming fully man without change so He remains fully God. He is the Bridegroom.

He Ascended intact as fully God and fully man.

I know when I meet a Protestant who is a lover of God, we don’t argue or contend with each other. We share our love of our Incarnate, Lord, God and Savior and in the process, bear one another’s burdens a bit too.

Nevertheless for our communion to be complete we must approach the Cup of Salvation together and partake of the Holy and Life-giving Body and Blood together as is recorded by the Apostle and Evagelist John in the sixth chapter of his Gospel.

Remember we Orthodox are not now, nor have we ever been Roman Catholics, Papists or any other description you care to apply to the Roman Church led by the Pope. As it stands now we have never been less in sympathay wiith them.

I worship every week with people who’s Christian lineage goes back to the earliest Apostolic missions in what is now southern Syria. Our Patriarchal headquarters in Damascus on a street called straight is dangerous right now but they continue to endure and offer us wisdom at the same time.. Almost 2000 years. My parish is officially 99 years old although the founders began gathering as a community much earlier than that. These people endured all of the Roman persecutions, the Turkish Yoke under which they were subjected to capricious slaughter as the founders had to flee the Turkish jihad in the late 19th century to stay alive. It may no longer be a Turkish Yoke, but the Islamic yoke still threatens. Yet faith and Orthodox worship continues in villages, in clergy, in monasteries, in bishops. Each strengthened by the Cross and the Body and Blood of our Lord.

I am grafted on.

God is good. Blessed be the name of the Lord.