Book Review: Early Christian Attitudes toward Images by Steven Bigham (3 of 4)

This blog posting is a continuation of my earlier reviews of Father Steven Bigham’s book. Chapter 1 & Chapter 2.

In this posting I will be reviewing and interacting with Chapter 3: “The Early Christians and Images.”

New Testament Evidence

Bigham notes that the New Testament is totally silent with respect to Christian or non-idolatrous images (p. 81). This silence can be understood in a number of ways. One is to view it as indicative of early Christian iconophobia. Another is that there were many things done and said by the Apostles that did not get entered into the written testimony of the New Testament (see John 20:30). All this is to say that we should not be surprised about the limited and partial picture of the life of the first Christians as we have it in the New Testament. The apostolic preaching, even though only partially contained in the New Testament, is nonetheless fully expressed in its essence.

Father Bigham notes that while the New Testament is silent with respect the use of non-idolatrous images, it is risky to argue from silence. He writes:

We are not claiming that the apostolic Christians did in fact make or order images of Christ, Mary or anyone else or that they produced any symbolic designs. We simply want to state that the silence of the New Testament on this question does not exclude the possibility of some kind of artistic activity (p. 82).

This leads him to note:

It is quite probable that the vast majority of 1st century Christians never thought about a Christian art. They did not have the time or money to make or order images, even if they wanted to. It is sufficient for our purposes that they did not show themselves hostile to a non-idolatrous art, and in fact, there is no evidence to indicate that they were hostile to such imagery (p. 83).

I would add another possible reason for the apparent silence on early Christian art. As faithful Jews the first Christians drew on the religious art already present in their Jewish tradition (see my review of Chapter 2).

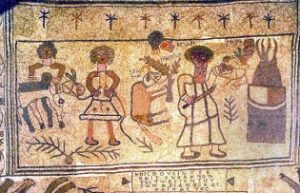

It is quite probable that the first Christians used the images of Abraham “sacrificing” Isaac, Moses at the Burning Bush, and the Three Youths on display in the synagogues as visual prophecy pointing to the coming of Christ.

Another factor to consider is that as pious Jews they had a keen appreciation for the visual displays on Herod’s Temple (see Luke 21:5-6) and were thus accepting of images used in connection with worship of Yahweh. The disciples’ acceptance of Jewish religious images of the time would account for the absence of first generation Christians challenging Jewish images because there was nothing to challenge.

In his examination of biblical passages where the word “eikon” (image) is used, Bigham examines Mark 12:13-17 where Jesus debates the lawfulness of paying taxes to Caesar and asks for a coin with Caesar’s image. Jesus’ attitude here contrasts with that of the more rigorist rabbis at the time who refused to even look at or handle such coins because they bore the idolatrous image of the Roman man-god (pp. 83-84). While the image on the coin is quite removed from the context of worship, Jesus’ tolerant attitude is quite instructive. The attitude of iconoclastic Protestants today is closer to the rigorist rabbis of Jesus’ time than the tolerant stance of Jesus and his followers (pp. 54-56).

Images in Early Christian Tradition

One of the most well known Christian images is the portrait of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child. There is an oral tradition that the original painter of the portrait was Luke the Physician. The earliest written record we have of this claim is the History of the Church by Theodore the Reader who lived in the fifth century (Bigham p. 90).

Another ancient tradition relates that the king of Edessa, Abgar, was sick and sent his ambassador, Ananias, to carry a letter petitioning Jesus to come and heal him. Jesus turned down the request but promised to send one of his disciples at a later date.

One version of the story relates that Ananias painted a picture of Jesus for the king and another that Jesus imprinted his features onto a wet cloth (Bigham p. 91). Eusebius in his Church History 1.13 gives a detailed account of this encounter and informs the reader that he himself examined Abgar’s letter at the royal archives of Edessa.

Eusebius in Church History 7.18 describes how there could be found in Caesarea Philippi a statue depicting Jesus healing the woman with the issue of blood, a reference to the healing miracle recorded in the Gospels (Mark 5:25-34, Matthew 9:20-22, Luke 8:43-48). In addition to the three dimensional statue, this same passage also contains a description of the custom among Christians of making images of Christ and the Apostles.

Eusebius wrote:

Nor is it strange that those of the Gentiles who of old, were benefited by our Saviour, should have done such things, since we have learned also that the likenesses of his apostles Paul and Peter, and of Christ himself, are preserved in paintings, the ancients being accustomed, as it is likely, according to a habit of the Gentiles, to pay this kind of honor indiscriminately to those regarded by them as deliverers (Church History 7.18; emphasis added)

These accounts by Eusebius point to images as part of early Christianity. It is not clear from these accounts that images could be found in places of Christian worship. The chief significance of these accounts is that they refute the notion that early Christianity was aniconic or universally hostile to icons.

Protestants learning of these early accounts may be dubious about the relatively late date of the written records and skeptical of the reliability of Christian oral tradition. First, the historical gap between the events and the written records is not all that huge from the standpoint of mainstream historiography. Second, the hostile attitude towards Christian oral tradition reflects a bias inherent in the Protestant theological principle sola Scriptura.

Sola Scriptura is intrinsically biased. It forces Protestants to ignore Scripture passages about the faithful passing on of the Apostles’ teaching whether in oral or written forms from generation to generation (2 Thessalonians 2:15; 2 Timothy 1:13-14, 2:2). Oral Tradition, of necessity, prevailed during the early decades before any New Testament Scripture were written down (much less widely copied and distributed). Phillip did not hop into the Ethiopian eunuch’s chariot with a bound New Testament in hand. Instead he explained Isaiah drawing on the oral Tradition he received from the Apostles in Jerusalem. The Apostles preached the Gospel, baptized converts, planted Churches, devised liturgies and ordained priests to serve the Church without a handbook to instruct them (Acts 13-14). It would be centuries before a recognized New Testament comprised of 27 books came into existence. The 27 book New Testament we know today reflects the dynamic development of Christian Tradition over several centuries. The Protestant bias against oral Tradition is largely an emotional reaction to medieval Roman Catholicism. There is good reason to suspect that Protestant iconoclasm was rooted in a similar reaction. We exhort our Protestant readers: Read your Bibles with a mind open to Oral Tradition!

A more rational approach would be to have an open mind and heart to early church history. Fr. Bigham notes:

Let us be clear here: in studying these traditions, we are not necessarily claiming that they are historical, but we are not claiming, either, that they are void of historical content. It is, in fact, impossible to establish or disprove their historicity (p. 89).

More recently, however, ethnographic, anthropological, biblical and historical studies have given researchers a more open mind about the possibility of gathering historical information from oral traditions that were written down at a considerable period of time after the events or people described (p. 89).

As part of his survey of early Christian sources, Steven Bigham examines two major figures who held to a rigorist interpretation of the Second Commandment. He notes that Tertullian handled the self-contradictory implications of his rigorist position by creating a listing of items exempt from the Second Commandment, e.g., the golden cherubim over the Ark and the bronze serpent (pp. 125-126). Another early Christian writer is Clement of Alexandria who resorted to allegorizing in order to account for the construction of cherubim and other images in the Old Testament Tabernacle (pp. 132-140).

The scope of Steven Bigham’s research in Chapter 3 is wide ranging. In addition to Christian sources, he surveys sources of dubious theological provenance that point to early use of images among quasi-Christian groups (see pp. 94-111). This makes Bigham’s book a valuable resource for anyone interested in researching early Christian attitudes towards image.

The Council of Elvira

In recent debates between Protestants and Orthodox Christians over the legitimacy of icons the Council of Elvira has been cited not a few times by those who oppose icons. This particular council took place in Spain during a period of relative peace during Diocletian’s rule, either 295-302 or 306-314. Canon 36 reads:

Placuit picturas in ecclesia esse non debere, ne quod colitur et adoratur in parietibus depingatur.

It has seemed good that images should not be in churches so that what is venerated and worshiped not be painted on the walls.

This text is significant because the word “picturas” is a clear reference to non-idolatrous, figurative representations (p. 162). Bigham notes that the meaning of Canon 36 is not as clear as iconoclasts presume. First, it is not clear what was being depicted on church walls. Were these abstract symbols or portraits of God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit? Second, we know nothing of the circumstances giving rise to this canon. Were the bishops afraid that these images could become subject to profanation by pagans, or were the bishops concerned about superstitious attitudes by members of their flock? (see p. 163).

The Council of Elvira was not a major council. The canons of this council were adopted by other councils but interestingly not Canon 36 (p. 165). Canon 36’s limited influence can be seen in the fact that Frankish Church in its opposition to the Seventh Ecumenical Council did not invoke the Council of Elvira. This is further supported by the fact that paintings on church walls were encouraged among the Franks. This leads Bigham to suspect that Canon 36 was a corrective action intended for a particular time and place; it was not intended as a universal prescription. In any event, two conclusions can be deduced from Canon 36: (1) it provides strong evidence that some form of paintings was put on church walls, and (2) it provides ambiguous support for the iconoclastic position. The biggest problem for the iconoclast is that Canon 36 does not support the argument that early Christianity was universally hostile to icons. At best it can be claimed that some early Christians were opposed to images.

As a minor council the Council of Elvira faded from view until the iconoclast controversy erupted during the Protestant Reformation some one thousand years later. There is a certain irony in the fact that an obscure regional council would be so widely “accepted” and cited by Protestants given that many Protestants treat the early councils with disdain or disregard.

The Mind of the Church

Opponents of icons claim that their opposition to icons are not just their opinion but reflect the mind of the early Church. Of their research of ancient Christian sources Bigham notes: “They also give equal authority to all the witnesses called to testify without any regard for the value of each witnesses’ testimony. The result is, therefore, a potpourri of witnesses….” (p. 171; emphasis added) Bigham’s review of early sources shows that if anything the early attitudes towards Christian images was mixed and that iconoclasm was not a majority position.

In assessing early Christian sources Bigham notes that these can divided into three groupings: (1) individual opinion, (2) theologoumenon – a respected opinion accepted by some but not by all, or (3) dogma – an opinion held by the Church universal. The last usually emerges during times of conflict and controversy. This points to the dynamic nature of Christian Tradition. Steven Bigham writes:

We have argued that Christian art passed through several stages in the course of its historical development: from indirect symbols, signs and images to direct images of historical persons and events. We have also stated that Christian art was a tradition that the Church adopted and adapted to its own needs (p. 169).

The dynamic nature of Christian Tradition can be seen in Christology. Early Christianity prior to Constantine shared a common Faith transmitted through its bishops. Irenaeus attested to the common faith shared by Christians across the Roman Empire.

Having received this preaching and this faith, as I have said, the Church, although scattered in the whole world, carefully preserves it, as if living in one house. She believes these things [everywhere] alike, as if she had but one heart and one soul, and preaches them harmoniously, teaches them, and hands them down, as if she had but one mouth.

The articulation of official theological dogmas stated in precise language would not emerge until the Ecumenical Councils beginning with Nicea I in 325. Over the next several centuries controversies would lead to rulings by Ecumenical Councils settling these matters decisively. One thing inquirers will find in Orthodoxy that is strikingly absent in Protestantism is the understanding of the Holy Spirit being active in the early Church. Many Protestants believe that the early Church fell into error and spiritual darkness shortly after the passing of the Apostles. In Orthodoxy pneumatology is integrated with ecclesiology, but in Protestantism pneumatology is for the most part independent of ecclesiology. So as one ponders the Ecumenical Councils it is important to see the Holy Spirit guiding Christ’s Church into all truth (John 16:13). This dynamic development of Tradition can be seen in the early simple confessions of Jesus as the Son of God to the Nicene Creed’s Christology articulated using precise and nuanced language.

Interestingly, it was not until the seventh century that the use of images in Christian worship became a major theological issue warranting a conciliar response. Bigham notes about the timing of the Church’s dogmatic stance on icons:

The Church formulated its attitude toward non-idolatrous images, and expressed that attitude, not in the pre-Constantinian period, but some four centuries later. In the fire of a crisis, during which the iconoclasts openly repudiated the tradition of Christian images, calling icons idols and veneration idolatry, the Church, and not just certain Christians, affirmed the legitimacy of this tradition by appealing to history and theology: to history, by claiming that images were made in the apostolic era; to theology, by stating that since the invisible God became visible in Christ, it is right to paint his earthly image. A tradition with a small “t” became part of holy Tradition with a capital “T”; it has become part of orthodoxy itself. (p. 172)

Thus, the Seventh Ecumenical Council’s affirmation of icons is not something added on but an affirmation of an implicitly accepted custom widespread among early Christians. Protestant iconoclasts suffering from historical amnesia have reached the mistaken conclusion that icons are a later addition. It then becomes something of a shock when they encounter historic Orthodoxy which claims to have kept the Apostolic Faith without change for the past two millennia and which defends images (icons) as part of the historic Christian Faith.

Assessment

Father Steven Bigham deserves credit for his unflinching examination of the early evidence relating to images in early Christianity. Reading this chapter will expose the reader to a wide range of sources: orthodox, heterodox, heretical, and even pagan. He is to be commended for working with evidence that is at times sparse, ambiguous, and at times of dubious provenance. While it is difficult to argue for the full fledge veneration of icons early on, the evidence Bigham surveyed pretty much refutes the notion of universal hostility to images among early Christians. The significance of Chapter 3 is that it significantly weakens the historical basis for the iconoclastic position. If true, this leaves Protestant iconoclasts clinging to theological bias as the sole ground for their opposition to Orthodox icons.

Robert Arakaki

One of the best books on icons, both about their history and theology, that everyone should read:

http://www.amazon.com/Theology-Icon-2-Volume-Leonid-Ouspensky/dp/0881411248

FYI: here’s a far broader context for the famous quote (end para 3) by Cardinal John Henry Newman on Church History per Protestantism:

(http://www.newmanreader.org/works/development/introduction.html)

“Accordingly, some writers have gone on to give reasons from history for their refusing to appeal to history. They aver that, when they come to look into the documents and literature of Christianity in times past, they find its doctrines so variously represented, and so inconsistently maintained by its professors, that, however natural it be à priori, it is useless, in fact, to seek in history the matter of that Revelation which has been vouchsafed to mankind; that they cannot be historical Christians if they would. They say, in the words of Chillingworth, “There are popes against popes, councils against councils, some fathers against others, the same fathers against themselves, a consent of fathers of one age against a consent of fathers of another age, the Church of one age against the Church of another age:”—Hence they are forced, whether they will or not, to fall back upon the Bible as the sole source of Revelation, and upon their own personal private judgment as the sole expounder of its doctrine. This is a fair argument, if it can be maintained, and it brings me at once to the subject of this Essay. Not that it enters into my purpose to convict of misstatement, as might be done, each separate clause of this sweeping accusation of a smart but superficial writer; but neither on the other hand do I {7} mean to deny everything that he says to the disadvantage of historical Christianity. On the contrary, I shall admit that there are in fact certain apparent variations in its teaching, which have to be explained; thus I shall begin, but then I shall attempt to explain them to the exculpation of that teaching in point of unity, directness, and consistency.

“Meanwhile, before setting about this work, I will address one remark to Chillingworth and his friends:—Let them consider, that if they can criticize history, the facts of history certainly can retort upon them. It might, I grant, be clearer on this great subject than it is. This is no great concession. History is not a creed or a catechism, it gives lessons rather than rules; still no one can mistake its general teaching in this matter, whether he accept it or stumble at it. Bold outlines and broad masses of colour rise out of the records of the past. They may be dim, they may be incomplete; but they are definite. And this one thing at least is certain; whatever history teaches, whatever it omits, whatever it exaggerates or extenuates, whatever it says and unsays, at least the Christianity of history is not Protestantism. If ever there were a safe truth, it is this.

“And Protestantism has ever felt it so. I do not mean that every writer on the Protestant side has felt it; for it was the fashion at first, at least as a rhetorical argument against Rome, to appeal to past ages, or to some of them; but Protestantism, as a whole, feels it, and has felt it. This is shown in the determination already referred to of dispensing with historical Christianity altogether, and of forming a Christianity from the Bible alone: men never would have put it aside, unless they had despaired of it. It is shown by the long neglect of ecclesiastical history in England, which prevails even in the English Church. {8} Our popular religion scarcely recognizes the fact of the twelve long ages which lie between the Councils of Nicæa and Trent, except as affording one or two passages to illustrate its wild interpretations of certain prophesies of St. Paul and St. John. It is melancholy to say it, but the chief, perhaps the only English writer who has any claim to be considered an ecclesiastical historian, is the unbeliever Gibbon. To be deep in history is to cease to be a Protestant.

“And this utter incongruity between Protestantism and historical Christianity is a plain fact, whether the latter be regarded in its earlier or in its later centuries. Protestants can as little bear its Ante-nicene as its Post-tridentine period. I have elsewhere observed on this circumstance: “So much must the Protestant grant that, if such a system of doctrine as he would now introduce ever existed in early times, it has been clean swept away as if by a deluge, suddenly, silently, and without memorial; by a deluge coming in a night, and utterly soaking, rotting, heaving up, and hurrying off every vestige of what it found in the Church, before cock-crowing: so that ‘when they rose in the morning’ her true seed ‘were all dead corpses’—Nay dead and buried—and without grave-stone. ‘The waters went over them; there was not one of them left; they sunk like lead in the mighty waters.’ Strange antitype, indeed, to the early fortunes of Israel!—then the enemy was drowned, and ‘Israel saw them dead upon the sea-shore.’ But now, it would seem, water proceeded as a flood ‘out of the serpent’s mouth, and covered all the witnesses, so that not even their dead bodies lay in the streets of the great city.’ Let him take which of his doctrines he will, his peculiar view of self-righteousness, of formality, of superstition; his notion of faith, or of spirituality in religious worship; his denial {9} of the virtue of the sacraments, or of the ministerial commission, or of the visible Church; or his doctrine of the divine efficacy of the Scriptures as the one appointed instrument of religious teaching; and let him consider how far Antiquity, as it has come down to us, will countenance him in it. No; he must allow that the alleged deluge has done its work; yes, and has in turn disappeared itself; it has been swallowed up by the earth, mercilessly as itself was merciless.” [Note 1]

“That Protestantism, then, is not the Christianity of history, it is easy to determine, …”

St. Paul seems to make an oblique reference, actually, to making (or processing/displaying) an image of “Christ Crucified” (a Crucifixion Icon) in Galatians. Very clear in the Greek:

“You foolish Galatians, who has bewitched you, before whose eyes Jesus Christ was publicly **portrayed as crucified**?”

The word translated as “publicly portrayed” (προεγραφη) here is not a theatrical word (how we often speak of a “portrayal” in English), but clearly derived from the root word “grapoi/graphei”, which means “picture(s)/written shapes-word(s)”.

As well, for poorly-informed people to protest the use of Christian image because of “silence” from the New Testament, the very word, “Icon/Eikona” is used without explanation, *because those reading the word would already be familiar with Icons already in use*. Religious/Liturgical iconography is clearly used in the Old Testament Temple, and in later Synagogues. That Christian worship existed as a Christ-fulfilled form of Jewish Liturgical worship should be plainly apparent (Hebrews 8:6, in the Greek, makes it clear that Christ received a *Liturgy* (not “ministry”, which is another word, διακονιας, meaning “service” – Liturgy is a distinctly, well, liturgical word)) superior to that of Moses. The Mosaic Liturgy, adapted to First and Second Temple worship, clearly used sacred images, both on the cover of the Ark, in the form of two 3-Dimensional golden Cherubim, and on the curtains – Chrubim guarding Trees), and elsewhere in the (gold-leaf lined) Temple and the courtyard (bronze bulls as base of laver, Brazen Serpent, etc.). The New Testament writings didn’t need to repeat every continuity, whether it was using (fulfilled/Christ-transformed) Liturgical art, or the ban on bestiality (not repeated in the New Testament writings but surely still prohibited, along with many other sins).

Given the nature of continuity with Jewish Second Temple and Synagogical worship for the original Church, being thoroughly Jewish, it would be incumbent on iconoclasts to show verses introducing a *new (to the Jews) ban* on religious images, then – their usage wouldn’t have to be re-explained. Their existence *is* Scripture (“graphoi”, meaning both “writings” and “paintings/drawings”) which has been passed down! They are another Apostolic tradition, along with the other New Testament writings.

http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=galatians%203%3A1&version=NASB;TR1894

Gregory,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! Thank you for your insights.

Robert

The verse from Galatians, above, is Galatians 3:1. Evident if you click the link, but I forgot to include the citation after the verse.