Two Approaches to the Trinity

The Reformed tradition’s monergistic premise is consequential, not just for soteriology, but for its understanding of the Trinity. This is because theology (the nature of God) and economy (how God relates to creation) are integrally related. To separate the two would result in a defective theological system. A comparison between the Eastern and Western theological traditions demonstrates how different approaches to the Trinity led to different understandings of salvation.

In the early Christological debates Christians struggled to reconcile the theological concepts of monotheism and monarchy (LaCugna 1991:389; Kelly 1960:109-110). The Cappadocian Fathers — Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzen — solved the problem by abandoning the principle of monarchy in favor of a trinitarian monotheism. They argued that the unity of the Godhead stems not from the Being (Ousia) of God but from the Person (Hypostasis) of the Father (Kelly 1960:264). Gregory of Nazianzen wrote:

The Three have one nature, viz. God, the ground of unity being the Father, out of Whom and towards Whom the subsequent Persons are reckoned (in Kelly 1960:265).

Zizioulas noted the emphasis on the hypostasis over the ousia has major implications for our understanding of the Trinity.

In a more analytical way this means that God, as Father and not as substance, perpetually confirms through “being” His free will to exist. And it is precisely His trinitarian existence that constitutes this confirmation: the Father out of love–that is, freely–begets the Son and brings forth the Spirit. If God exists, He exists because the Father exists, that is, He who out of love freely begets the Son and brings forth the Spirit (Zizioulas 1985:41; emphasis in original).

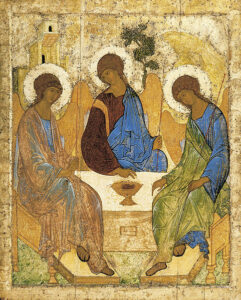

The Cappadocians grounding the doctrine of the Trinity in the Persons, not the Being, provides a solid basis for the statement in I John 4:16: “God is love.” Love is not an attribute of God but what God is: the Trinity of Persons forever united in love. Thus, God is not an isolated Individual, a monad but a communion of Persons.

God exists as the mystery of persons in communion; God exists hypostatically in freedom and ecstasis. Only in communion can God be what God is, and only as communion can God be at all (in LaCugna 1991:260).

Augustine took a different approach from the Fathers in emphasizing the divine Essence (Ousia) in constructing his doctrine of the Trinity (LaCugna 1991:91; Kelly 1960:272). This theological move arose from his locating relationality within the divine Being. Zizioulas observed that this emphasis on the Godhead as a Trinity of coequal Persons tends to push the Essence (Ousia) to the forefront.

The subsequent developments of trinitarian theology, especially in the West with Augustine and the scholastics, have led us to see the term ousia, not hypostasis, as the expression of the ultimate character and the causal principle (αρχη) in God’s being (Zizioulas 1985:88; emphasis in original).

Vladimir Lossky in The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church noted:

The Latins think of personality as a mode of nature; the Greeks think of nature as the content of the person (1976:58).

This monumental theological move by Augustine shaped the theological trajectory of Western Christianity for generations – extending even to the present day.

The result has been that in textbooks on dogmatics, the Trinity gets placed after the chapter on the One God (the unique ousia) with all the difficulties which we still meet when trying to accommodate the Trinity to our doctrine of God. By contrast, the Cappadocians’ position–characteristic of all the Greek Fathers–lay, as Karl Rahner observes, in that the final assertion of ontology in God has to be attached not to the unique ousia of God but to the Father, that is to a hypostasis or person (Zizioulas 1985:88; emphasis in original).

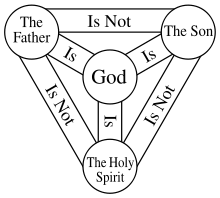

Western Christianity’s foregrounding of the ousia (being) of God has led to logical difficulties. It has resulted in theologians having to make statements that resemble Zen koans used by Buddhist monks. A common explanation often goes like this: the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God; but the Son is not the Father, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit; but there is not three gods but only one God. Formulation like this often frustrate and bewilder many. It is radically different from the Eastern understanding of the Trinity as the communion of three Persons who share in the same Essence.

Western Christianity’s foregrounding of the ousia (being) of God has led to logical difficulties. It has resulted in theologians having to make statements that resemble Zen koans used by Buddhist monks. A common explanation often goes like this: the Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God; but the Son is not the Father, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit; but there is not three gods but only one God. Formulation like this often frustrate and bewilder many. It is radically different from the Eastern understanding of the Trinity as the communion of three Persons who share in the same Essence.

The most prominent manifestation of the Western Augustinian approach is the Filioque clause. As originally phrased the Nicene Creed implied that the Holy Spirit originated from the Person of the Father but the insertion of the Filioque implied the Holy Spirit originated from the Essence shared by the Father and the Son (Filioque). Lossky writes about the Filioque:

The Greeks saw in the formula of the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son a tendency to stress the unity of nature at the expense of the real distinction between the persons. The relationships of origins which do not bring the Son and the Spirit back directly to the unique source, to the Father–the one as begotten, the other as proceeding–become a system of relationships within the one essence: something logically posterior to the essence (Lossky 1976:57).

Thus, the Filioque marks a theological watershed between Western Christianity (Roman Catholic and Protestant) and Eastern Orthodoxy. It can also be considered as the beginning of the West’s innovative approach to doing theology.

A Theological Continental Divide

A Theological Continental Divide

There is a place in the Continental Divide where a stream veers off in two directions. One branch ends up in the Pacific Ocean and the other the Atlantic Ocean. Similarly, with Augustine and the Cappadocian Fathers a theological equivalent of the Continental Divide emerged that would result in two quite different theological systems.

Augustine’s focus on God’s being as the starting point for theologizing has been consequential for the way salvation has been understood in the West (Lacugna 1991:97). One disturbing implication of Augustine’s approach to the Trinity is the sense of God as impersonal inscrutable One.

If divine substance rather than the person of the Father is made the highest ontological principle–the substratum of divinity and the ultimate source of all that exists–then God and everything else is, finally, impersonal (LaCugna 1991:101; emphasis in original).

A theological system based on an impersonal and omnipotent deity leads to a monergistic soteriology and the subsequent denial of free will and love. The doctrines of Unconditional Election and Irresistible Grace assume an all powerful God who in his inscrutable wisdom unconditionally elects a few then inexorably effects their salvation. It is almost as if the Augustinian West might say of our election or reprobation: “It’s not personal, it’s just abstract ontology.”

The Protestant Reformers in their quest to uphold the dogma of sola fide with its implicit monergism had to choose between the God’s abstract/impersonal sovereignty and God’s personal and relational love. Calvin, with unflinching clarity, upheld the sovereignty of God and the principle of monergism with all its terrifying implications in his explication of double predestination. By leaving no room for free will, Calvin’s theology led to a relapse to monarchical monotheism undermining the basis for trinitarian monotheism.

The Western Augustinian approach to the Trinity provides the basis for a forensic soteriology which views salvation in terms of legal righteousness and the transference of merit. The forensic approach contains two significant assumptions: (1) the relationship between God and mankind is understood in terms of an impersonal command-obedience and (2) rather than Man in the “image and likeness of God,” it assumes an ontological divide between humanity and God. The penal substitutionary atonement theory being based on the transfer of merit maintains the ontological gap between God and humanity. Notably, it does not require communion between God and the elect.

Where Western theology tends to maintain the ontological gap between God and humanity, Orthodoxy emphasizes the gap being bridged in the Incarnation. The gap being bridged here by Christ’s incarnation is ethical-relational, humanity being sullied by sin and in need of healing and reconciliation. There is also an ontological gap which is bridged by Christ who unites divinity and humanity in one Person. The Incarnation makes possible a personal encounter with God because the Son assumed human nature from the Virgin Mary. According to the Chalcedonian Formula, the human and divine natures are joined in the Person of Jesus Christ. The technical term for this is hypostatic union. The significance of the hypostatic union is that a person to person encounter such as that implied by faith in Christ is crucial to our salvation. The priority of the hypostasis means that a physical viewing of the Christ “according to the flesh” is not enough (cf. II Corinthians 5:16), a true encounter with Christ entails trust in Christ. The story of the woman with the issue of blood in Mark 5:24-34 shows that the woman’s personal encounter with Christ was more important than physical contact with the hem of his clothes. The interconnection between being and person is crucial for our salvation in Christ which culminates in our deification — humanity “partaking of the divine nature” by grace what Christ is by nature (see II Peter 1:4).

The Cappadocians’ stress on the hypostasis (person) leads to Orthodoxy understanding salvation as relational: with God and with others. Through faith in Christ we come to know the Father and receive the Holy Spirit; we are made members of the Church, the body of Christ. What we do collectively as the Church takes precedence over what I do individually in private. Through the sacraments of baptism and chrismation the convert is reborn into the life of the Trinity. This is because the sacraments are covenantal actions based upon an interaction or exchange between persons. The Orthodox emphasis on the hypostasis means that every sacrament is a personal encounter with God.

Person and being are dynamically linked, what affects the one, affects the other. This interrelationship helps us to understand the Orthodox teaching of theosis — our ongoing transformation into the likeness of Christ and deification (sharing in the divine nature). Theosis assumes that through our union with Christ, the Incarnate Word of God, and our receiving the Holy Spirit we become “partakers of the divine nature” as taught by the Apostle Peter in II Peter 1:4. In theosis we remain human but we are transformed by divine grace. We are transformed much like the way the metal sword in the fiery furnace becomes hot and bright like the fire while still remaining metal. Where Western theology has a tendency to be mechanistic and deterministic in its soteriology, Eastern Orthodoxy has a more relational and dynamic approach.

Calvinism and the Western Tradition

There is no indication that the Reformers broke from the Western Augustinian tradition and followed instead the Eastern approach to the Trinity. Steven Wedgeworth in his essay: “Is There a Calvinist Doctrine of the Trinity?“ sought to rebut theologians who advanced the idea that Calvin broke from the Nicene trinitarian tradition and offered a modified trinitarian doctrine. Pastor Wedgeworth argued that far from offering a new theological paradigm, Calvin remained faithful to the traditional Nicene trinitarian theology. However, Wedgeworth failed to note that what Calvin advocated was the Western Augustinian understanding of the Trinity. Furthermore, he failed to note that there existed an alternative understanding of the Trinity, the Eastern Cappadocian approach. Wedgeworth’s failure to discuss the Cappadocian approach is disappointing especially because in end note 27 is a quote from Calvin which sounds very much like the Eastern Fathers. Calvin wrote of God the Father: “He is rightly deemed the beginning and fountainhead of the whole divinity” (Institutes 1.13.25). While this sentence could be interpreted to mean that Calvin had some sympathy for the Eastern approach, it needs to be reconciled with his acceptance of the Filioque.

This leads me to pose two questions for my Reformed friends:

(1) Has the Reformed tradition critically assessed the Filioque clause in light of the Orthodox criticism?, and

(2) Has any Reformed denomination ever considered repudiating the Filioque and returning to the original language of the Nicene Creed (381)?

Coming soon — Does Reformed monergism have heretical implications?

Robert Arakaki

Robert, I think that it would be better to say that, in the light of a more opened in love towards God’s creation Spirit of the New Testament, brought by the life and teachings of the Divine Person of Jesus Christ, the Cappadocian Fathers christian theology went deeper into the understanding of Godhead than the Mosaic religion did and it revealed the truth of the trinitarian monotheism, than to say that the respective Fathers would have “abandoned” something, whatever it would have been, since the concept of the uniqueness of the Godhead, the same the revealed Itself in the Old Testament, continued to exist and Its unity was related to the Person of God the Father, as you wrote.

Cristian,

According my sources the early Christians struggled with reconciling Christ’s divinity with the monotheism they received from the Old Testament. One attempt was dynamic monarchianism, also known as “adoptionism,” which claimed that Jesus was a “mere man” upon whom God’s Spirit descended. The early Church rejected this as heretical (see JND Kelly’s Early Christian Doctrines p. 115). The early Christians never abandoned the monotheism taught by Moses and the prophets. They continued be monotheists but through the trinitarian monotheism articulated in the Nicene Creed. I hope this addresses your concerns.

Robert

Most scholars today, even Orthodox guys like Hart, reject the de Regnonian paradigm you listed above. I can find quotes by Nazianzen where he simply defines God as “Being,” which sounds Western.

When you mentioned the one nature of the Trinity, do you mean “generic” or “numeric?”

Finding a word used likewise in the West or sounding similar is a far cry from an actual adherence to any particular theology. Do you have some citations of his works to so that we may be privy to the overall context of such statements?

John

Off the top of my head I think it is Oration 29. I agree that the later middle ages did view God the way Robert suggests. Joachim of Fiore specifically nailed Lombard on this point, saying he preached a quaternity.

Still, as Orthodox guys like Hart admit, this hard East-West divide breaks down in the earlier church.

I readily admit the use of “Western” terminology, like juridical language for example, in the east. But it never evolved into what we now see in Western Christianity. Big difference in my eyes.

Thanks for the source!

Well, if the term denotes the content (“juridical language), then it isn’t necessarily wrong in the conclusions we draw from it.

If juridical terms (as found in the NT) denote juridical concepts, then those concepts are found in the NT.

If juridical terms do not denote juridical concepts, then they are emtpy and useless terms.

Jacob said

“Well, if the term denotes the content (“juridical language),”

But isn’t that a “Concept / Word” fallacy? Isn’t it anachronistic to read American Law back into first century juridical language?

Jacob said

“If juridical terms (as found in the NT) denote juridical concepts, then those concepts are found in the NT.”

But what if the 1st century understood those juridical terms(as found in the NT) in a particular way that’s different from how 16th century folk in Western Europe saw it? Or 19th century North American folk saw it?

Jacob said

“”When you mentioned the one nature of the Trinity, do you mean “generic” or “numeric?””

If one doesn’t believe the Essence to cause the Persons then does it really matter?

Generic unity doesn’t really talk about the specifics of how something is one. It just says that various particulars have something in common. In this case the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit having Divinity in common.

Both Mormons and Christians can believe this and so it doesn’t really focus on the unity question of how the Son is one with the Father. But if one looks at the Creed of Nicea in 325A.D. as a whole then the unity question is implicitly stated for the Eternal Generation of the Son doctrine is what’s behind this statement here:

http://www.antiochian.org/674

quote

“And in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Only-begotten, Begotten of the Father before all ages, Light of Light, True God of True God, Begotten, not made, of one essence with the Father, by Whom all things were made:”

And so generic unity can mean both:

Three Ice Cubes on a table separated/disconnected/isolated……etc in distance from each other. Or it could mean two streams flowing from a River.

A polytheistic modern Mormon is able to agree with the three Ice Cubes example of generic unity, but is unable to agree with the One River and two Streams example of generic unity.

Thus anyone who thinks that Nicea of 325 A.D. represented the first example is wrong. It should be obvious to all that the view of the Son being Eternally Generated from the Father and the Holy Spirit Eternally Proceeding from the Father is what Christianity had in mind.

And if one focus on the unity of the Three Persons (from what I just said above) then the implications of that should also be obvious. And so back to my original question. If one doesn’t believe the Essence to cause the Persons then does it really matter?

For to deny the Unity is to deny what Nicea of 325 A.D. was trying to say implicitly anyway. And as we all know, Christians are not tri-theists. We are Monotheists!

So why deny the Nicene-Constantinople 1 Creed of 381 A.D.? Especially if one lacks the view of the Essence causing the Persons? Why deny it?

Wouldn’t this make the Nicene-Constantinople 1 creed of 381 A.D. the logical conclusion of Nicea of 325 A.D.?

I am fully aware that the link of the creed I gave is from 381 A.D.

I quoted it because the first part of the Nicene-Constantinople 1 should be similar. I saw one difference in this area, but I didn’t feel like typing it from the books I have in front of me. I thought it would be easier to just cut and paste from a link.

I am also fully aware that what I said about the Holy Spirit wasn’t fully articulated in 325 A.D. For the creed at that time only said “and in the Holy Spirit.” and then it goes on with a number of anti-Arian statements.

But before Nicea and before the rise of Arianism, a number of Church Fathers and Christian witnesses, and maybe even a couple schismatics made statements of the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father (thus the idea wasn’t really new) , and so instead of going into all this detail and instead of talking about the evolution of what happened decades after Nicea (in focusing more on the Holy Spirit) it was easier to simply talk about all Three Persons, instead of just Two Persons, which is what we mostly see a focus of when looking at a number of their writings. For I was trying to get a particular point across. I wasn’t really trying to get lost in the details.

I just asked a simple question. No need for the dissertation.

We will apply the question a different way: how many minds are in the trinity?

Jacob,

Drake’s view is not just 3 minds. It’s 3 natures, 3 minds, 3 wills…..etc. In the context of 3 individual human beings. Like Father, Mother, child…..etc.

One can only take that metaphor so far before it breaks down. When one denies the Godhead to be Indivisible and Undivided, then you are advocating some form of tri-theism.

The idea of Indivisible and Undivided is not something exclusive to post Nicene Orthodox Triadology. For it can be found being advocated in the Pre-Nicene, as well as Nicene eras as well. Thus, it shouldn’t be fought against. It should be embraced!

An excellent article. One thing that I would suggest is that if one looks at Calvin’s Christology, it very quickly becomes apparent that despite h is claim to accept Chalcedon, his basic approach is Nestorian. This is apparent in his Eucharistic theology where he rejects any real presence of Christ because he believes that the body of Christ is in heaven and any presence of Christ in the Eucharist is spiritual, thereby dividing the human and divine natures as well as rejecting the deification of the human nature of Christ.

Why does Calvinism have such an appeal? It seems that there is a growing neo-Calvinist movement within American Evangelicalism and even within continuing Anglicanism. Even before I became Orthodox, I found the Calvinist view of God frightening.

Jnorm:

***But isn’t that a “Concept / Word” fallacy? Isn’t it anachronistic to read American Law back into first century juridical language?***

I thought about that, and that’s why I avoided arguing any specific content into what I meant about “juridical” (since it wasn’t the main point of the past few comments). I was addressing the argument, as it appeared to me, that even though the NT uses “juridical” language, it can’t mean *that.*

The Orthodox writer Vladimir Moss has made the exact same observation on some orthodox thought that I just made.

***But what if the 1st century understood those juridical terms(as found in the NT) in a particular way that’s different from how 16th century folk in Western Europe saw it? Or 19th century North American folk saw it?***

So, the grammatical-historical method?

As someone who had to memorize/study the Three Forms of Unity in high school catechism. Thank you for helping me understand how orthodox theology relates to the Reformers.

The judicial understanding of salvation of the West came about by Western theologians like Tertullian and especially Augustine reading the concepts of Roman Law into the New Testament text. In Protestantism, it is no accident that both Luther and Calvin studied law before they turned their attention to theology.

I have been severely jolted by the presentation of the differences in how eastern and western Christianity view the Trinity in this blog and TULIP (4). I have never before had the opportunity to see any view of the Trinity other than the western. Does not the western view leave it susceptible to the charge of tritheism? It will take me some time to digest this. Now I begin to see the possibility that the Filioque is more than just a matter of conciliar procedure.

Harold,

Thank you for your comment and question. From what I’ve observed, Protestants are susceptible to modalism — the belief that the three Persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit represent different modes or aspects of God. An elder at my former Protestant church — who was involved in the charismatic movement — criticized his fellow Evangelicals for being “binitarian” — focusing on Jesus and God while ignoring the Holy Spirit. Among the more liberal mainline Protestants there is a tendency to view Jesus as a good man, an exemplary human being, which is a form of unitarianism. i strongly suspect that because many Protestants approach the Trinity as a philosophical construct, it is hard to maintain the proper balance between the ousia (being) and the hypostases (persons) in the Trinity. Orthodox has done a better job of maintaining this balance due to its reliance of liturgical theology. The doctrine of the Trinity is sung, chanted, and prayed every Sunday in the Liturgy.

Robert