A Response to Pastor Toby Sumpter

On 3 March 2016, Pastor Toby Sumpter posted on Reformation21 “An Apostolic Case for Sola Scriptura.” In this article he argues that canon formation of the New Testament proves the Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura. He writes:

In fact, there is a strong case to be made that the apostles and first Christians knew what books would form the New Testament canon very early on. The reason they knew was because the task of writing the New Testament Scriptures was one of the central purposes of the office of apostles. (Emphases added)

And,

The center of the evidence for a largely completed canon by the death of the apostles is grounded in understanding the office of apostle itself. (Emphasis added)

Toby Sumpter’s attempt to prove a very early New Testament canon (before AD 100 or even during the lifetime of the Apostles) makes sense in light of recent Reformed and Orthodox apologetics debate over sola scriptura. One major criticism of sola scriptura is the argument that if it took several centuries for the New Testament canon to emerge then that means the early Church functioned quite well without sola scriptura. This in turn raises the question whether sola scriptura is necessary.

All too often Protestant attempts to defend sola scriptura confuse the writing of the New Testament texts (corpus formation) with that writing being recognized as uniquely inspired (canon formation). While closely related, the two are not the same. Among conservative Christians there is little debate about the New Testament texts having been written in the latter half of the first century. The difference lies more with the Church’s recognizing the texts as divinely inspired, that is, as Scripture.

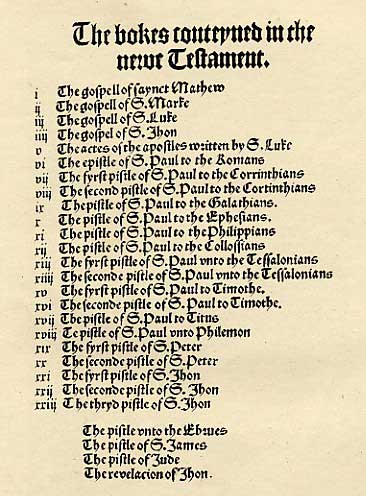

Where did this list come from? Who made it? Source

There are two competing theories of how canon formation took place. A prolonged canonization process would suggest the Church functioned under oral Apostolic tradition for the first few centuries and without sola scriptura. (Remember, John Mark did not write his synoptic gospel first for at least twenty years.) A compressed canonization process would leave little room for oral Apostolic Tradition. A very early completion to the canonization process would give rise to a listing of authoritative New Testament (canon) to guide the early Church in matters of faith and practice. If one takes the extreme position – as does Toby Sumpter – that the New Testament canon was completed while the Apostles were still living then there was zero room for oral Apostolic tradition to guide the early Church. This is because the early Church had a complete list of Scripture from the get go (as argued by Toby Sumpter).

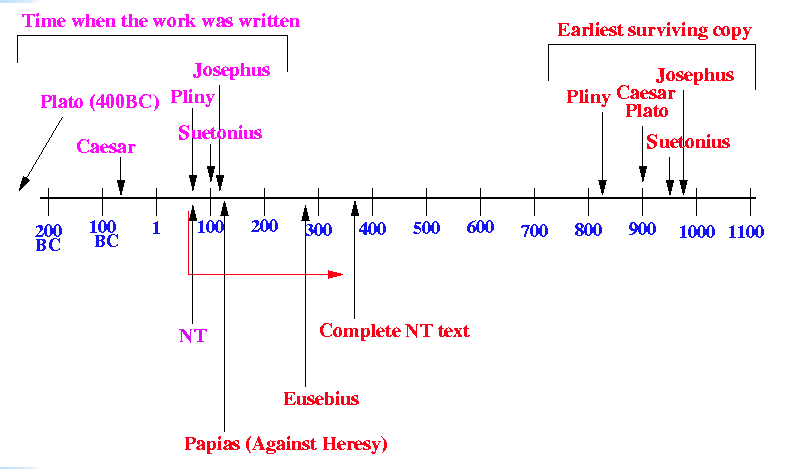

Chart showing the mainstream understanding of canon formation – Source

The New Testament Project?

Pastor Sumpter puts forward the interesting theory that in light of the Great Commission the Apostles devoted themselves to the production of canonical Scriptures for the Church.

Here, I argue that the apostles were quite conscious of this goal. Jesus had entrusted to them the “testimony” not merely for a small band of Jews in Jerusalem, but they were to be witnesses throughout Judea and Samaria and to the ends of the earth. How would that testimony reach the ends of the earth intact without devolving into an elaborate telephone game? The apostles and their assistants almost immediately began writing. This is because the apostles knew that their office was responsible for preserving and passing down the authoritative testimony of the gospel of Jesus. This is why every New Testament book was written or sponsored by an apostle. (Emphases added)

From the above excerpt we find Pastor Sumpter making at least three claims: (1) that the Apostles were conscious of their responsibility to write canonical Scripture, (2) that Jesus made writing part of the Great Commission, and (3) that the Apostles in obedience to this mandate began writing canonical Scripture right away. But does Scripture support any of these claims?

First, if the Apostles were “quite conscious of this goal,” then we would expect to find them discussing their responsibility to produce an authoritative collection of writings that testify to Jesus Christ. Where’s the evidence? A careful search of the Gospels, the book of Acts, and the letters by Paul and other Apostles leaves us empty handed. We find is that the Apostles did write but wrote when the occasion called for it (Romans 15:15; 1 Corinthians 4:14, 5:9-11; 2 Corinthians 2:3-4, 13:10; Galatians 1:20; Philippians 3:1; 2 Thessalonians 4:9, 5:1; 1 Timothy 3:14; Philemon 19-21; 1 Peter 5:12; 2 Peter 3:1; 1 John 1:4, 2:1; Jude 3).

Second, there is no evidence that Jesus made writing part of their apostolic calling. When we look at the Great Commission passage in Matthew 28, and other similar passages: Mark 16:15-20, Luke 24:45-49, John 20:21, and Acts 1:1-8, we find not a single shred of evidence indicating that Jesus ever did so. As a matter of fact, in the longer ending to Mark’s Gospel Jesus commands the Apostles: “Go into all the world and preach (κηρυξατε) the good news to all creation.” Likewise, in Luke 24:47 we read: “repentance and forgiveness of sins will be preached (κηρυχθηναι) in his name to all nations.” The Greek κηρυσσω has the sense of public proclamation by voice; it would be a stretch to say that it means writing. According to Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament one of key qualifications of a herald (κηρυξ) was a good voice (vol. III p. 686). The sole exception is the book of Revelation where Christ tells John: “Write (γραψον), therefore, what you have seen, what is now, and what will take place later.” (Revelation 1:7, cf. 21:5) However, this command applies only to the book of Revelation. If Toby Sumpter’s argument did hold up, we would have seen other earlier commands for the other New Testament texts but no such evidence for this can be found.

Third, there is the fact that none of the New Testament texts have been dated back to the 30s or 40s. The earliest New Testament texts are either Paul’s letter to the Galatians or 1 Thessalonians. Scholars estimate that Galatians was likely written after AD 52 and that 1 Thessalonians has likewise been estimated to have been written in the early 50s. Mark’s Gospel is believed to have been written around the time of the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70. Matthew’s Gospel and Luke’s Gospel have been estimated to have been written circa AD 80. Furthermore, much of Paul’s letters were written in response to pastoral emergencies. The evidence here point to a gradual and sporadic production of New Testament texts. This would fit in with a theory that writing was a secondary aspect of apostolic ministry. If Pastor Sumpter’s theory is valid then one has to ask: Why did the Apostles wait twenty to forty years to begin writing canonical texts?

Another problem with Sumpter’s theory is that so few of the Twelve wrote canonical materials. Where are the writings of Apostle Thomas? I would love to read his account of Jesus’ death and resurrection. Where is the writing of Apostle Peter’s younger brother Andrew? And where are the writings of Thaddeus, Nathaniel, Philip, and the others? Why is it that we don’t have their written testimony to the Good News of Christ?

We need to take into consideration the small number of New Testament authors. From the Apostle Peter we have Mark’s Gospel and Peter’s two letters. We have from the Apostle John the Gospel that bears his name, three letters, and Revelation. We have Matthew’s Gospel and nothing else from him. Then we have the Gospel authored by Paul’s companion, Luke, who also authored the book of Acts. From the Apostle Paul we have a collection of a dozen letters. Hebrews has been traditionally attributed to Apostle Paul. This comes to a total of four apostolic composers of the New Testament corpus. Why so few? Where are the others? That is a question that raises doubts about Toby Sumpter’s theory.

For an Orthodox Christian the small number of composers of the New Testament corpus is not a problem. The Apostles were busy proclaiming the Good News of Christ, leading the early liturgies, and ordaining elders (Acts 6:2, 13:1-3, 14:23). From time to time they would write a letter if the occasion called for a written response but writing was not a core function of an Apostle, preaching was.

An Exaggerated Problem

Pastor Sumpter sketches what he purports to be a “popular theory” that he will refute.

A popular caricature of the process of canonization (a somewhat problematic phrase in its own right) is that tons of early Christians wrote tons of stuff and that it was only after the deaths of the first generation of Christians or so) when the subsequent generation of Christians suddenly woke up and began scrambling to collect as many meaningful looking scraps as they could find, like grabbing flecks of confetti blowing around in the wind. And the Holy Spirit led the Church to find all the right pieces and paste them all together just right (Emphasis added).

And,

. . . which I summarize as: The complete canon of Scripture was not determined until centuries after the apostles, and the Church (led by the Holy Spirit) determined what the canon of Scripture was. Therefore, the Scriptures derive their authority from the Church.

While a fascinating theory, it’s one I never heard of. It would help if Pastor Sumpter had referenced his sources for this theory. Perhaps Pastor Sumpter’s “caricature” is really only “popular” in certain select small Protestant splinter groups? Should we not favor the more widely accepted understanding that there was widespread reception of Paul’s letters and the four Gospels early on followed by a more gradual and contested reception of James, 2 Peter, Hebrews, and Revelation, combined with the eventual exclusion of disputed but popular texts like the Shepherd of Hermas and 1 Clement. This understanding of canon formation is similar to F.F. Bruce’s explanation which reflects the overwhelming mainstream of New Testament scholarship. (See link.)

Just as important is the mechanism by which canon formation took place. F.F. Bruce points out that it was not by means of a formal list that canon formation happened. He writes:

One thing must be emphatically stated. The New Testament books did not become authoritative for the Church because they were formally included in a canonical list; on the contrary, the Church included them in her canon because she already regarded them as divinely inspired, recognising their innate worth and general apostolic authority, direct or indirect.

He notes that the canon list created in the North African synods, Hippo Regius (393) and Carthage (397), did not impose something new on the churches but rather codified what had already been a general longstanding practice.

A Very Interesting Theory

Pastor Sumpter draws on E. Randolph Richards’ theory of how the New Testament canon came about. Richards notes that it was a widespread practice for ancient writers to keep on hand copies of their correspondence. Then he speculates that the New Testament canon was completed when Peter and Paul ended up in Rome before their martyrdom. Sumpter summarized Richards’ theory as follows:

Given the fact that Peter ended up in Rome at around the same time as Paul, and Luke is there already with Paul, and Mark is on his way (2 Tim. 4:11), we have all the indications that one of the first apostolic New Testament canon committees was holding session there in Rome in the mid 60s A.D. And if all that weren’t enough, don’t forget the fact that Peter refers to Paul’s letters as Scripture right around the same time (2 Pet. 3:15-16). In other words, the apostles knew what they were doing.

Add in John’s gospel, letters, and apocalypse, and we’re there. (Emphasis added.)

I don’t know what Toby Sumpter means by “we’re there” but I can tell you that it does not mean that he has proven his case! All he has done is sketch out an internally consistent hypothesis that awaits supporting evidence. What evidence is there that Peter and Paul were in Rome at the exact time in the mid 60s? And that Peter and Paul actually collaborated on finalizing the New Testament canon? And if he wants to really make his case, show how Hebrews and James came to be included in the New Testament canon in Rome in the mid 60s. What we have here is an interesting – if not a self-serving speculation? – theory that awaits solid evidence. This is far removed from the accepted mainstream of biblical scholarship.

Is the Muratorian Canon a List?

When we look closely at the Muratorian Canon (dated back to AD 170), what we find is not so much an authoritative listing of apostolic writings (which is what we would expect according to Pastor Sumpter’s theory) but an attempt to describe the books accepted by the early Church. What is striking about the Muratorian Canon is evidence that point to a traditioning process. In line 71 reference is made to the apocalypses of John and Peter being received:

We receive only the apocalypses of John and Peter, though some of us are not willing that the latter be read in the church. (tantum recipimus quam quidam ex nostris legi in eclesia; lines 71-72) (Emphasis added.)

The rather puzzling phrase that “some of us” were reluctant to have Peter’s apocalypse being read in church point to the autonomy of the local bishop and their liturgical authority. And in line 81 we read that nothing from heretical writers like Arsinous, Valentinus, or Miltiades ought to be received by the churches.

… which cannot be received into the catholic Church – for it is not fitting that gall be mixed with honey. (arsinoi autem seu valentini vel mitiadis nihil in totum recipemus; line 81). (Emphasis added.)

If Pastor Sumpter’s theory of canon formation held up, we would not be reading a lengthy description of books read out loud in the early Church. Rather, we would be reading a short succinct listing of titles and the assertion that this is a copy of an authoritative codex listing the Apostles Peter and Paul’s writings as proposed by Randolph Richards.

Did Irenaeus Use a Canonical List?

One of the earliest witnesses to the New Testament canon is Irenaeus of Lyons (d. circa AD 195). To combat the heretics Irenaeus defends the four-fold Gospel in Against Heresies 3.11.8-9 (ANF Vol. 1 pp. 428-429). He writes:

It is not possible that the Gospels can be either more or fewer in number than they are. For, since there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds, while the Church is scattered throughout all the world, and the “pillar and ground” of the Church is the Gospel and the spirit of life; it is fitting that she should have four pillars. . . .

The first thing to note is that Irenaeus takes the four-fold Gospel as an undisputed given. This points to an early development in canon formation with respect to the Gospel. Upon closer examination we find that Irenaeus gives us a lengthy description of the four Gospels. This is significant because he does not appeal to an official list of canonical Scripture which is what we would expect if Toby Sumpter’s theory held up. The formal listing represents a later stage of canon formation. In the early days of the Church the transmission of Scripture was part of a traditioning process. Irenaeus writes:

For if what they [the heretics] have published is the Gospel of truth, and yet is totally unlike those which have been handed down to us from the apostles, any who please may learn, as is shown from the Scriptures themselves, that that which has been handed down from the apostles can no longer be reckoned he Gospel of truth (AH 3.11.9, ANF p. 429; emphases added).

[Note: the Latin original has “ab Apostolis nobis tradita sunt” and “ab Apostolis traditum est veritatis Evangelium.” (Bold added) Source]

One important element in Pastor Sumpter’s argument is the notion that the production of written apostolic texts lay at the core of the Great Commission project. This implies that missionizing without written Scripture would be gravely deficient but this is not what we find in Irenaeus.

To which course many nations of those barbarians who believe in Christ do assent, having salvation written in their hearts by the Spirit, without paper or ink, and, carefully preserving the ancient tradition . . . .

Those who, in the absence of written documents, have believed this faith, are barbarians, so as regards our language; but as regards doctrine, manner, and tenor of life, they are, because of faith, very wise indeed . . . . (AH 3.4.2; ANF p. 417; emphases added)

It is important for Protestant readers to recognize that Irenaeus was not denigrating the importance of written Scripture but that his emphasis was on Apostolic Tradition in both written and oral forms. Irenaeus did not assume a tension between written and oral Apostolic tradition; nor did he assume a hierarchical ordering in which written tradition was superior to oral traditions. Rather he assumed written and oral Apostolic traditions to be complementary to each other.

Athanasius’ Festal Letter

In AD 367, almost two centuries after the Muratorian Canon and Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great issued his annual Paschal (Easter) letter to the Diocese of Alexandria. It is here that we see the formal listing of canonical Scripture (NPNF Vol. IV, pp. 551-552). That Athanasius needed to distinguish between canonical and apocryphal books shows how much the early Church relied on the process of reception. This would not be the case if there had been a precise list from the start as would be the case in Pastor Sumpter’s theory. Evidence for the traditioning process can be seen in the way Athanasius described the reception of Scripture texts:

. . . . as they who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers o the Word, delivered to the fathers; it seemed good to me also, having been urged thereto by true brethren, and having learned from the beginning, to set before you the books included in the Canon, and handed down, and accredited as Divine. (Letter 39, NPNF Vol. IV pp. 551-552; emphases added).

When we compare Athanasius’ approach to the biblical canon with early approaches we find a gradual transition from informal reception of Apostolic writings by local bishops to formal definition by the Church Catholic. Contrary to what Pastor Sumpter assumed, the early Church did not confer apostolic authority onto the New Testament texts; rather the early Church through its bishops recognized the New Testament texts as apostolic and rejected all others as spurious.

This raises serious concerns about Pastor Sumpter’s own theory and the purported problem that he seeks to address. Sumpter’s theory assumes a static listing of canonical scripture right from the time the Apostles Peter and Paul were alive. One, there is no evidence of such a hard and fast listing early on. What we do see is an early general consensus over the core of the New Testament with a few writings over which a general consensus would emerge centuries later. Two, there is no evidence for the “rival theory” that there was a blizzard of competing texts that forced church authorities to arbitrarily define as Scripture. Pastor Sumpter is welcome to defend his theory of canon formation by showing us the historical evidence that support his theory. What I have done is give an alternative theory of canon formation which is more in keeping with the general scholarship and is supported by evidence from the Muratorian Canon, Irenaeus of Lyons’ Against Heresies, and Athanasius the Great’s Festal Letter of AD 367.

Where’s the Bishop?

One missing element from Prof. Richards and Pastor Sumpter’s model of canon formation is the role played by early bishops. There’s no mention of the bishops at all in Sumpter’s article. This is a serious flaw given the importance of the bishop in early Christianity. Early bishops were ordained by the Apostles to lead the church and to preserve and pass on the Apostles’ teachings. They were tasked with preserving the Apostolic teaching whether in written or oral form. In the early days, the bishop had the authority to determine what would be read as Scriptures in the Sunday liturgy.

The apostolic basis of the early episcopacy explains the quick acceptance of the Petrine and Pauline corpus of the New Testament. As disciples of the Apostles the bishops were able to distinguish genuine apostolic teachings from heretical counterfeits. The need for synods where bishops gathered to decide on Hebrews, James and 3 John point to the importance of the early Church being guided by the Holy Spirit in the reception of these texts. What we do not find in the early sources is a top-down imposition of a canonical list. What we find are bishops gathered in synods seeking to reach a consensus as to what was apostolic.

Conclusion

This lengthy response is warranted by Toby Sumpter’s theological agenda – to prove that sola scriptura was part of early Christianity and not a late sixteenth century Protestant invention. Pastor Sumpter’s article is regrettably rife with guesswork, inference, and surmise. What we have found in our review of his article is an elaborate theory lacking in evidence. Given the lack of supporting evidence, the best thing for Pastor Sumpter is to admit that sola scriptura is a sixteenth century Protestant innovation. It represents a new approach to doing Christian theology that breaks from historic Christianity.

In contrast to Toby Sumpter’s speculative approach, I have taken an evidence based approach showing that the formation of the New Testament canon cannot be understood apart from the traditioning process. Evidence have been presented from Scripture, the church fathers, and church history for the Orthodox understanding of the New Testament canon formation, that is, through the traditioning process. The Orthodox Church through its bishops can trace its lineage back to the original Apostles. Through the past two millennia the Orthodox Church has faithfully preserved the physical text of Scripture as well as the right interpretation of the Scripture.

The debate over canon formation is far from a trivial matter. Canon formation requires an apostolic Church, a Church where its leaders have been ordained by the Apostles and their successors, and have in their possession Scripture through the traditioning process. Protestants lacking this historical traditioning process end up bootlegging sacred Scriptures.

Robert Arakaki

References

Athanasius the Great. “Festal Letter XXXIX.” NPNF Vol. IV, pp. 551-552.

F.F. Bruce. “The Canon of the New Testament” in Bible-Researcher.com

Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies. ANF Vol. I.

“The Muratorian Fragment.” Bible-Researcher.com

E. Randolph Richards. 1998. “The Codex and the Early Collection of Paul’s Letters.” Bulletin for Biblical Research 8 (1998) 151-166.

Even if Mr. Sumpter was correct, I would still have to question why other doctrines espoused by the Reformed Church do not line up with the teachings of the Saints who lived shortly after the Apostles.

Again, If Sumpter is correct, the Apostles would have written the New Testament, but would not have explained the reformed doctrines to their disciples.

Good points!

It is sad indeed to see our protestant friends continue to strain ever-new theories dreamed up, against the historic consensus of early Church scholarship. Patristic Church scholars do not debate such things.

But then we forget the protestant spirit is one of the primary genesis of the modern revolutionary spirit. This spirit has been nurtured Enlightenment philosophers, French Jacobins, Russian Bolsheviks, and modern Jihadists revolutionaries. To different degrees & style, they all love to destroy & re-write history to conform to their agendas.

How would you respond to someone like HE Met. Kallistos Ware, who has publicly said that he sees no basic difference between Sola Scriptura and the Orthodox doctrine/use of Scripture as the heart and primary source of Holy Tradition? For Ware, because Holy Tradition is merely the ongoing life of the Holy Spirit in the Church from age to age expounding the meaning of the Scriptures through Councils, Creeds, Fathers, Liturgy, Saints, and Icons, there is no fundamental difference in his mind between the Orthodox perspective and Sola Scriptura, since everything that the Spirit is revealing is merely the interior meaning of the Scriptures.

In Ware’s support, it’s worth noting that to the earliest Christians “Scriptures” referred exclusively to the Old Testament, while the New Testament was designated by “apostolic writings,” which themselves functioned within a larger matrix of apostolic tradition and authority; hence, Papias writes that there are written and oral traditions of NT material and he prefers the oral. In other words, Sola Scriptura is true if by Scripture we mean to denote Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms (the demarcations for the Tanakh given us towards the end of Luke’s Gospel), since the whole of the Tradition would thus be a commentary on how the Scriptures illuminate the Gospel of Israel’s Messiah, Jesus, the primary and authoritative articulation of which are the apostolic writings. (For more on this, see Fr. John Behr, The Mystery of Christ: Life in Death.)

David,

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware’s presentation of Orthodoxy is on the whole very balanced and nuanced. Also, he strives to be irenic in his approach to other faith traditions. I suspect that some Protestants may have misunderstood what he had to say about sola scriptura. I suspect your question is based on a garbled paraphrase. What is needed is an exact quote as well as information about the occasion of that statement. My guess is that Metropolitan Ware was trying on that particular occasion to emphasize the commonality between the Orthodox and Protestant traditions, and not play up the differences.

But getting back to your original point, as a former Protestant I can quite understand how one can misunderstand an Orthodox statement and have the impression that it is identical to the Protestant position. The two traditions have much in common but there are important differences.

Sorry, I have not yet read Fr. John Behr’s book. However, to apply sola scriptura to Papias who lived in the second century would be taking sola scriptura out its proper historical context, the 1500s. Such an approach would make hash of historical theology and end up generating more confusion than better understanding between the Protestant and Orthodox traditions.

Robert

Robert

I am a Minister within a “Restoration” splinter whose emphasis has always been sola scriptura. However, I cannot deny what History teaches concerning the canon and it does not support Pastor Sumpter’s theory on canon formation. In fact, history does not support sola scriptura. The theories we create to support our beliefs would be comical if not so disturbingly sad. We overlook or ignore historical facts to our own detriment….I should become Orthodox already….

Adam,

I appreciate your honesty about your situation. If you feel led to become Orthodox, a good first step would be to get in touch with a local Orthodox priest. May God’s merciful presence be with you as you begin your journey!

Robert

Hi Robert,

I wonder if you could comment on the issue of 2 Peter 3:16 in relation to Pastor Sumpter’s thesis that the apostles were not attempting to write Holy Scripture – it’s very clear that St. Peter writes as if the writings of St. Peter were scripture at the time.

Ryan,

It is clear that the Apostle Peter understood Paul to be writing with apostolic authority. The question here is whether Peter, Paul, or the other apostles were engaged in a writing project, that is, to generate a comprehensive set of Scriptures, and that this project involved the making of a comprehensive listing of Scriptures. Pastor Sumpter seems to be under the impression that there was an attempt to create a definitive set of sacred writings binding on all Christians. My assumption is that Peter and Paul wrote spontaneously, as the occasion arose; it was only later that the Church via the bishops attempted to create a listing of apostolic writings. I don’t see 2 Peter 3:16 pointing to the making of a definitive set. In other words, I see 2 Peter 3:16 as referring to corpus formation, not canon formation.

Robert

Hi Robert and Ryan,

There is no word in Greek for Scripture. Graphe can either mean ‘writings’ or ‘Scriptues’, depending of the lens you are looking through. Normal pagan writings were referred to in a similar way. With 2 Peter 3:16 in is unclear what is being twisted, it is the Old Testament or other writings of the Apostles. Graphe could be either.

Stefano,

You have a good point here. The word “Scripture” has accumulated layers of meaning that wasn’t there in the early Church. When Christians today read “Scripture” with a capital “S” they at least think of: (1) a well defined set of writings, (2) writings that are divinely inspired, and (3) authoritative for all Christians. So when we read 2 Peter 3:16 we need to guard against imposing our contemporary mental paradigms uncritically. For me as an Orthodox Christian I read Scripture through the eyes of the Church. I also attempt to understand Scripture using the exegetical tools I learned at Gordon-Conwell. It’s an interesting tension that can yield interesting insights.

Robert

Robert

Robert,

It has been a long time since I’ve commented. I hope you are well.

I wrote something awhile ago that you might find interesting in this debate:

http://russwarren.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-scriptures-and-traditions-of-men.html

God’s blessings on you, sir.

RVW

Hi Russ,

Nice to hear from you! And nice article. You made some good points in it.

Robert

thanks russ…good article.

Hi Robert,

I think your article hits the nail on the head. You are exactly right that Sola Srciptura supporters often confuse corpus formation and canon formation. I realised this after about my 20th debate on the topic. I haven’t come across the term ‘corpus formation’ before but it is a handy term to use. Thanks.

Also, I feel that the evidence from Irenaeus is often overstated. He had an apologetic purpose to stress the use of the 4 Gospels. Certainly the use of four Gospels was widespread in the early Orthodox/ Catholic Church but there is evidence to suggest not all followed this.

1) the incident at Rhossus where Serapion of Antioch allowed the provisional reading of the Gospel of Peter pending his investigation. Notice that Serapion did not give an automatic ‘no’.

2) the Syriac Church had the Diatessarion rather than 4 Gospels

3) Bodmer Papyrus XIV is a codex of Luke/John from the early third century – this shows that not everyone felt the need to include all four Gospels in a single codex

4) An anti-Montanist group in Asia Minor (dubbed the ‘Alogi’ by Epiphanius of Salamis) rejected the Johanine Corpus, including the Gospel of John, but seemed to have been Orthodox in everything else.

5) Aramaic speaking Jewish-Christians called Nazareans seemed to use an Aramaic version of Matthew and no other Gospel. (There were heretical Jewish/Christians who had a low christology but the Nazareans were Orthodox in christology but followed Jewish customs).

Any thoughts Robert?

Stefano

Stefano,

As I was reading through Pastor Sumpter’s article and thinking about the argument he was making the phrase “corpus formation” popped into my head. I’m glad you found the “corpus formation” versus “canon formation” distinction helpful. It certainly helped me figure out the issues in Sumpter’s article.

With respect to your additional sources all I can say is that I’m in awe of your knowledge of early Christianity! But let me add that a critical distinction needs to be made between mainstream or Catholic Christians, and deviant or heterodox sects. I would place in the latter category the Alogi (4) and the Nazareans (5). If they are deviant sects not in communion with Jerusalem, Antioch, and Rome, then the question of canon formation is irrelevant. I wasn’t able to find enough evidence relating to Bodmer Papyrus XIV to determine if it had bearing on the question of the four Gospels. So I’ll pass on your point #3. Moving backwards to point #2 I’m under the impression that the Diatessaron was an attempt to harmonize the four Gospels. If anything, they affirm the four Gospels but I don’t think it sheds light on what the second century Church regarded as worthy of reading in the Sunday Liturgy.

And with respect to point #1 I think Bishop Serapion’s letter to the community of Rhossus against the so-called Gospel of Peter is relevant to our discussion of canon formation. There’s so little go by but I find it interesting that Bishop Serapion had to write an argument against it. But what were his reasons for objecting? Did he invoke a definitive listing of gospels? Did he argue that Apostle Peter only wrote a certain number of books? Did he say this is not part of our tradition? But what I find so striking is that the issue of the canonical listing of Gospels — the core of the New Testament — was in question in the minor town of Rhossus at the end of the second century. This would contradict Pastor Sumpter’s argument for an early closure to the New Testament canon. Furthermore, it would bolster my point about the important role played by the bishops in determining what was capital “S” Scripture in the early Church.

Again, thank you. I learned much from your question!

Robert

Hi Robert,

1) There is much about early Christianity that we don’t know. The only evidence about Serapion of Antioch and the Church at Rhossus is from Eusebius’ Church History. He seems to have derived it from the work of Serapion against the Gospel of Peter. I’m afraid that means your questions can’t be answered. It appears that Serapion objected to the Gospel of Peter on the grounds that it included docetism. Funnily, a large section of the Gospel of Peter, dating to the 6th/7th century, was discovered in a monks tomb a century ago and it’s not particularly docetist unlike the texts of the Nag Hammadi Library.

2) Even though it is called the ‘Diatessarion’ Tatian appears to have used a fifth source other than the four Gospels. It is unclear if it was a written source or an oral source. If you look at the Diatessarion you can see that a bit of cutting and pasting took place. It starts with John’s prologue then goes to Luke’s account of John the Baptists birth followed by Matthew account of the birth of Jesus, etc. Needless to say this strategy means that Tatian dealt with the Gospels rather freely. He had to decide where events fitted in (like the cleansing of the Temple – beginning or end of Jesus ministry), last supper, crucifixion and what to harmonise. If he thought that the Gospels were Scripture he wouldn’t have taken this approach.

In the 5th century Theodoret of Cyrrhus found 200 parishes in his diocese still using the Diatessarion. He had them replaced with the 4 Gospels.

4)I mention the Alogi because they were basically orthodox. No one even mentions them before Epiphanius and they had no name. This suggests that no one in 3rd century Asia Minor was really outraged at their rejection of John. It was as if it was still a ‘valid’ opinion. Epiphanius admits to coining the name ‘Alogi’ after coming across some of their writings. It appears that they attributed the Gospel of John to the gnostic Cerinthus.

5) There were a number of heretical Judeo-Christian groups but there was one that was fairly Orthodox and praised by Jerome. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church describes them as ‘Nazarenes occurs also as a name given by 4th-century writers to groups of Christians of Jewish race in Syria, who continued to obey much of the Jewish Law though they were otherwise orthodox Christians.’

Church Fathers disliked their adherence to the Law but they don’t criticise them for using only one Gospel.

I realise these two groups were on the fringes of Orthodoxy but critiques of them by contemporary authors don’t make the issue of canon a point of contention.

The Marcionites (a definately heretical group) only used an edited version of Luke’s Gospel. It has been argued that this was because Marcion’s home church in Sinope, where he grew up, only used Luke.

Finally, the Church in Persia (Assyrian, Nestorian or East Syrian – whatever you want to call it) had a 22 book NT up to the 19th century when Protestant missionaries convinced them to adopt the standard 27 book NT. Yes, they are heretical but also an ancient church. If the 27 books were an obvious collection it is strange that they didn’t use it.

Thanks Robert – I have found this a stimulating discussion.

Stefano,

As I said earlier, I’m impressed with your knowledge of the early Church. For now, I’ll let others interact with your observations.

I would like to add to your last point about the Church in Persia the fact that where the Persian churches had less than the 27 book NT canon, the Ethiopian Orthodox church has more than the 27 book NT canon. Please check out their website. I think this would be a bigger problem for Protestants due to the critical importance of sola scriptura for their theological system.

Again, thank you for this interesting discussion.

Robert

This doesn’t prove or disprove one point or another, it does show God’s care for his written and verbal word.

If Christ or his disciples were to craft a Canon it would seem that they would make a comment similar to Samuel when he spoke of Saul.

25Then Samuel explained to the people the custom of the king, and he wrote it in a book and placed it before the Lord. And Samuel sent all the people away, and every man went to his place.

Hi Travis,

I would disagree. It shows that while the Apostles wrote a set of texts (corpus formation) it does not mean they established an authoritive collection (canon).

You are correct that the God ( or more precisely the Holy Spirit) preserves the Word of God but I would add that it happens in the Church. I would also say that the Holy Spirit would also preserve accurate interpreters of Scripture.

I’m not sure what your quote from Samuel is trying to prove. It’s like insert random Old Testament quote here. Samuel writing one book is very different from the 27 books of the New Testament with 9 or 10 authors.