John Calvin source

On 23 May 1555, John Calvin preached on Deuteronomy 4:15-20 applying Moses’ admonition against idols to the depicting of Jesus Christ in icons. This sermon is significant for Reformed-Orthodox dialogue because it presents us not only with Calvin’s hermeneutical method but also the theological reasoning underlying his iconoclasm.

In my article, “The Biblical Basis for Icons,” I pointed to the use of images of cherubim on the curtains of Moses’ Tabernacle and images of cherubim carved on the walls of Solomon’s Temple. Then in another article, “Calvin Versus the Icon,” I wondered about Calvin’s failure in his Institutes or his commentaries to address these pro-icon passages. This made me curious about how Calvin would have responded to these passages in the Bible that support images in the church. It turned out that Calvin in his 1555 sermon did address this issue. We are fortunate to have Arthur Golding’s English translation of Calvin’s sermon series on Deuteronomy posted online by the University of Michigan. The reader should keep in mind that Golding (1536-1606) lived in the sixteenth century which accounts for what seems to us peculiar English spelling.

And whereas the alledge that there were Cherubins painted vppon the vaile of the Temple,* and that two likewise did couer the Arke: it serueth to con∣demne them the more. When the Papistes pre∣tend that men may make any manner of image: What, say they? Hath not God permitted it? No: but the imagerie that was set there, serued to put the Iewes in minde that they ought to abstaine [30] from all counterfeiting of God, insomuch that it was a meane to confirme them the better, that it was not lawfull for them to represent Gods Maiestie, or to make any resemblance thereof. For there was a vaile that serued to couer the great Sanctuarie, and againe there were two Cherubins that couered the Arke of ye couenant. Whereto commeth all this, and what is ment by it, but that when the case concerneth our going vnto God, we must shut our eyes and not preace [40] any neerer him, than he guideth vs by his word? Then let vs hearken to that which he teacheth, and therewithall let vs bee sober, so as our wits bee not ticklish, nor our eyes open to imagine or conceiue any shape. (Emphases added.)

Calvin’s reasoning here is a curious one. He argues the cherubim were depicted in the Temple: (1) to condemn the Israelites and (2) to remind them to abstain from making idols. It is as logical as a teetotaler parent’s taking a drink in order to teach his children to abstain from alcohol, or a college professor copying another professor’s work in order to teach his students the wrongfulness of plagiarism. In my earlier assessment of Calvin I took an irenic stance by titling the sub-section “The Logic of Calvin’s Iconoclasm.” However, Calvin’s peculiar exegesis in this sermon leads me to a quite different conclusion: “The Illogic of Calvin’s Iconoclasm.”

When reading the Old Testament it is important for Christians to interpret the text in light of the coming of Christ. In his sermon, Calvin applies Deuteronomy against the Roman Catholics as if they were living in the Old Testament dispensation. Calvin here seems to have skipped over the Incarnation. This is a huge omission because the early Church Fathers saw the Incarnation as a “game changer.” Prior to the coming of Christ humanity was estranged from God and pagans sought to worship God in the light of their understanding of him. This led to all sorts of pagan rituals and idols, and erroneous beliefs about his character. God’s meeting with Moses on Mt. Sinai marked the beginning of the restoration of the true knowledge of God which would culminate in the coming of Christ. John of Damascus explained how the Incarnation was a game changer.

It is clearly a prohibition against representing the invisible God. But when you see Him who has no body become man for you, then you will make representations of His human aspect. When the Invisible, having clothed Himself in the flesh, become visible, then represent the likeness of Him who has appeared. When He who, having been the consubstantial Image of the Father, emptied Himself by taking the form of a servant, thus becoming bound in quantity and quality, having taken on the carnal image, then paint and make visible to everyone Him who desired to become visible (in Ouspensky 1978:44).

As a result of the Incarnation the life of Christ takes on a revelatory character. We come to know God’s character not just through the teachings and sayings of Christ but also through his actions. The Orthodox Church sees the Trinity being revealed in Christ’s baptism in the Jordan and his transfiguration on Mt. Tabor.

John’s First Epistle likewise makes the case that in the Incarnation God the Son became visible and tangible.

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched…. (1 John 1:1; emphases added)

Calvin’s polemic against images makes sense if God was up in heaven far beyond human knowing and comprehension. In the Old Testament times it was impossible for man to ascend up to the heavens by his own power to behold God. Knowledge of God was only possible if God condescended to come down from heaven and showed himself to the patriarchs: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, or on Mt. Sinai as he did with Moses or through the prophets like Isaiah or Jeremiah. God’s condescension culminated in his taking on human flesh and dying on the Cross (Philippians 2:5-11).

Are Icons Nestorian?

Calvin makes another argument against depicting Christ in images. He argues that to depict Christ in images is a form of the Nestorian heresy.

Beholde, they paint and portray Iesus Christ, who (as wee knowe) is not onely man,* but also God manifested in the flesh: and what a representation is that? Hee is Gods eternall sonne, in whom dwelleth the fulnesse of the Godhead, yea euen substantially. Seeing it is said, substantially, should wee haue portraitures and images whereby the onely flesh may bee re∣presented? Is it not a wyping away of that which is chiefest in our Lorde Iesus Christ, that is to wit, of his diuine Maiestie? (Emphases added.)

In this passage Calvin makes two arguments. First, he affirms the two natures of Christ: human and divine. Second, he argues that because only the human nature can be depicted in a painting the result is a Nestorian heresy in which Christ’s humanity is separated from his divinity.

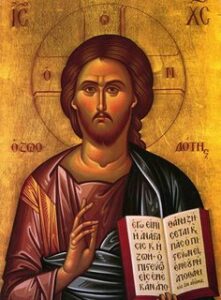

Orthodoxy has two responses to this. One, the icon depicts the Person of Christ. This can be seen in the prominence of the face in icons. Therefore, when Orthodox Christians venerate an icon of Christ their devotion is directed to the Person of Christ, not to his physical nature or the colored paint on the wooden board. The Person of Christ encompasses both his divine and his human natures. Two, Orthodox icons of Christ have symbolic references to Christ’s divinity. Typically, in the Pantocrator icon we see Christ’s red tunic overlaid with the blue mantle. The underlying red symbolizes Christ’s essential divine nature whereas the blue symbolizes his taking on human nature as an act of grace.

The visual depiction of Christ’s humanity is accompanied by symbolic references to his divine nature. We see inscribed on the Pantocrator icon the Greek phrase “Ο ΩΝ” which means “He Who Is.” This is taken from the book of Revelation:

Holy, holy, holy

Is the Lord God Almighty,

Who was, and is, and is to come.

(Revelation 4:8)

For the Orthodox Calvin’s theological critique of icons is fundamentally flawed. His ignorance of the principle that icons depict the person leads him to a Nestorian understanding of icons. In other words it is Calvin who is committing the heresy of Nestorianism, not the pro-icon Orthodox! We don’t know what kind of images Calvin saw in the Roman Catholic churches of his time but in Orthodox iconography there are safeguards in place to guard against Nestorian heresy that viewed his humanity as separate from his divinity.

Conclusion

For an Orthodox Christian, Calvin’s sermon against images is seriously flawed. One, Calvin’s neglecting to interpret Deuteronomy in the light of the Gospels, i.e., the Incarnation of the Word, results in anachronistic hermeneutics. He criticizes the use of images in Roman Catholic churches as if they were living in Old Testament times. Two, Calvin’s reading of Old Testament passages where God instructed Moses to have images of the cherubim woven into the Tabernacle curtains as being iconoclastic in intent make no sense whatsoever. Three, Calvin’s accusation of the implicit Nestorian nature of icons shows a fundamental misunderstanding of icons in Orthodoxy. Calvin’s accusation of Nestorianism holds up if evidence can be shown that the Church Fathers or Ecumenical Councils understood icons as depicting only Christ’s human nature. Four, Calvin’s failure to see icons depicting the Person of Christ leads him to an inadvertent Nestorian heresy.

If a Reformed Christian visiting an Orthodox Liturgy were to observe an Orthodox Christian venerating an icon of Christ they should refrain from jumping to the conclusion that the Orthodox parishioner is worshiping the painting of Christ or his physical nature. When an Orthodox Christian venerates an icon he or she is showing love and respect to the Person who came down from heaven and died on the Cross for their sins.

It may be that Calvin’s iconoclasm was the result of his being embroiled in the heated Protestant versus Roman Catholic polemic of the time. Reformed Christians today are fortunate to have the opportunity to engage in dialogue with Orthodox Christians who are familiar with both the Reformed and the Orthodox theological traditions. [I am grateful for the grounding in Reformed theology that I received at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary prior to my becoming Orthodox.] Icons have been a longstanding stumbling block between the two traditions. If it can be shown that Calvin’s iconoclasm is based on a flawed understanding of icons and that the Orthodox pro-icon position is grounded in Scripture then the possibility emerges for a rapprochement between the two traditions.

Robert Arakaki

See also:

“Are Images of Jesus Idolatrous?” by Jason Goroncy in Per Crucem ad Lucem.

“What is Calvin’s Take on Images of Jesus?” by Eric Parker in The Calvinist International.

“Are icons Nestorian?” in Wicket’s Take.

Theology of the Icon by Leonid Ouspensky, Volume I (1978).

If Calvinism is a Nestorian heresy then how is it possible to reconcile with us? In your posts on worship you said or implied that Protestant worship is in no way worship of the true God, so I have to assume that the Orthodox think us pagans.

Dawit,

Orthodoxy does not regard Protestants to be pagans. They often refer to Protestants as heterodox. This is in recognition that historically Protestants affirm the Trinity, Jesus being both human and divine, and his saving death on the Cross. This can be seen in the way Protestant converts are received into Orthodoxy. In some jurisdiction they accept as valid Protestant baptism and receive the convert through the sacraments of Chrismation and the Eucharist. In other jurisdictions converts are baptized, chrismated, then given the Eucharist. The latter more stringent approach is closer to the traditional manner of receiving heterodox. Reception via Chrismation is a form of “oikonomia” (relaxing of the rules).

The goal of the OrthodoxBride is to help Reformed Christians interested in Orthodoxy. Back when I was in seminary I was interested in Orthodoxy but was held back by theological problems I perceived in Orthodox beliefs and practices. As I stated in “Welcome” the goal of the blog is to ultimately help Reformed and Evangelicals to learn about Orthodoxy and in time to cross over. The reception of the 2000 Evangelical Orthodox in 1987 gives me hope that a similar movement will take place among the Reformed as well. I find the recent interest in the Liturgy, the Eucharist, and church fathers among Reformed Christians encouraging. However, in my interactions with Protestants I find that icons continue to be a big stumbling block. The goal behind my critiques like this one is to give Protestants good reasons for relinquishing mistaken beliefs and returning to their historic Christian roots.

Robert

A former pastor defined heresy as anything that gets between Christ and his disciples and hinders their spiritual walk and growth. Thus there can be weak heresy which all churches have to a greater or lessor degree and strong heresy that removes or should remove any claim to be Christian. I tend to see the health and wealth groups as close to strong heretics although of course God may still have a remnant of redeemed even there. Similarly with the state oriental Orthodox church where I grew up. As I said, from my reading of Orthodox writers I often get the feeling that the Orthodox consider none Orthodox Christians to be strong heretics. On the other hand some Orthodox authors seem very close to holding a semi Pelagian position rejecting damage from the fall almost to the extent that grace is not required for conversion as man’s free will was not significantly impaired, and this seems to me not to be strong heresy but heresy never the less. Some reformed seem to be learning and affirming of much truth that is upheld by the Orthodox. Deification, Eucharist as more than symbolic, Visual representation of our faith and so on. Often our differences are made worse by different vocabulary. In places the Reformed and the Orthodox have similar views for example a physical existence on a physical redeemed earth (after Christs return). Synergy vrs monergy of course is a big issue as is Constantianism since most or at least many reformed groups have moved away from Calvin and Luther in this area. Thank you for writing that we may understand and learn from each other. Unfortunately I have yet to find a reformed blog that I find worth reading, especially the output of the high federal Calvinists who seem like determinists to me.

Search for gingoro’s comment and the answer by Roger Olson for further lack of understanding re the Orthodox position on the topic of grace required at conversion.

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/rogereolson/2016/02/a-classic-book-about-corporate-election-revised-enlarged-and-re-published/

“In other words it is Calvin who is committing the heresy of Nestorianism”

When you read the whole sermon I think Calvin suffers less from Nestorianism than he does from a Platonic dualism, as he and the other scholastic humanists of his day were heavily influenced by Aristotle. A person Calvin simply, and sadly, refers to as “The Philosopher” in his writings. While he does make this passing swipe at Nestorianism in iconography, his overall gist is that despite whatever benefits imagery can provide, when it comes to worship they only serve to lower our minds upon earthly and fleshly things instead of upwards to a solely spiritual experience. This piestic understanding of material=bad and spiritual=good mentality definitely serves to the detriment of his teaching, as it denies both the beauty and intrinsic good of creation and our place in it.

“he does from a Platonic dualism, as he and the other scholastic humanists of his day were heavily influenced by Aristotle”

Aristotle wasn’t a Platonic dualist, so your argument here seems pretty fragile.

And meanwhile, Plotinus was a Platonic dualist who generally took the body to be evil, and he was influential to many Church Fathers. That doesn’t mean the Church Fathers also took the body to be evil.

I am not a big fan of this attempt to discredit theologians by trying to link their doctrines to some Greek philosopher who is supposedly antithetical to Christianity.

I would agree with you that guilt by association is bad argumentation, as well as a logical fallacy, but I think it is another thing to be critical of a specific influence when that person quotes them approvingly. However, I do want to thank you for pointing out how I did too readily jump to such labels rather than dealing with Calvin’s viewpoint specifically, since in reality any dualism that Calvin reflects would be neither truly Platonic or Aristotelian as a system. It is just an easy, or perhaps lazy, way of communicating a criticism without going into much detail or specifics. Also, I think many of us instinctively find wisdom in Tertullian’s words when he questioned “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem” or the “Academy with the Church” and so are quick to be critical of someone’s connection to Greek philosophical thought, despite the fact that just about any discussion on philosophy or theology is going to demonstrate its influence. After all, even Tertullian was influenced by Stoicism.

I actually wasn’t trying to discredit Calvin as a theologian, I was just being critical of some of his viewpoints. In fact I find his commentaries invaluable and would classify myself as Calvinistic, but definitely not a Calvinist in the true sense of the word. Likewise, Aristotle was not a disciple of Plato but he was a student for about 20 years and Aristotelian dualism does find its root in the Platonic version. Since Aristotle was the more popular of the two at the time, though Calvin did quote both, I tend to think that many Platonic themes that took root in Scholasticism were probably filtered through Aristotle and so I see a chain that sort of incorporates both. I am not enough of a scholar on the subject to know that for sure, so perhaps some if not all of them came directly from Plato. My main point would be that others more knowledgeable than me have pointed out that Calvin’s dualism is more reminiscent of Plato rather than Aristotle even though Aristotelianism over and against Platonism was the dominant school of thought for Scholasticism. This is why in a more truncated form I would make the statement that he suffers from Platonic dualism and this is probably due in large part to Aristotle’s influence and his connection to Plato. Though to be fair I am sure there are many that arrive at forms of Christian-dualism by simply reading Scripture and concentrating on those verses that speak of keeping our thoughts above and going to heaven while disregarding our charge to expand the Kingdom on earth and our final destiny in the re-creation. Now I would never classify Calvin as a dualist overall, it’s just that some of his viewpoints come close to it.

As to Plotinus, I find it somewhat disconcerting that Church Fathers would look to him since the Neoplatonism that he developed, and which was subsequently inherited by Porphyry, Iamblicus, Sopater, and utilized by people like Julian the Apostate, was intentionally meant to be a systematic worldview that served as a counterweight against Christianity’s rise and the Roman Civilization’s demise. But perhaps this is like quoting David Berlinski to criticize Richard Dawkins 🙂

I just have to add, even though I disagreed with you about Plato, I agree with what you say about Calvin otherwise.

“Calvin’s reasoning here is a curious one. He argues the cherubim were depicted in the Temple: (1) to condemn the Israelites and (2) to remind them to abstain from making idols. It is as logical as a teetotaler parent taking a drink in order to teach the children to abstain from alcohol.”

I think you are misunderstanding what Calvin was arguing here. He was not saying that the veil and images of the cherubim served to condemn the Israelites, rather the condemnation falls on the Papists who use this as a proof text for their license to make images of God because that is the one thing that was explicitly excluded from any depiction amongst all the other images that were allowed. For example, imagine this line of argumentation – “Because there were pictures of angels and palm trees in the Temple, it gives up permission to paint a picture of God the Father on the ceiling of our chapel”.

Not only was any imagery of God excluded, the coverings of where God’s presence was indicated by the veil and Cherubims reinforced to the Israelites that they cannot witness and should not even imagine a shape or representation of God. So in regards to the teetotaler parent analogy, a better ‘image’ of Calvin’s argument would be that the parent drinks water, coffee, tea, or soda in front of the child, but then puts a bottle of alcohol behind a locked and covered cabinet. I hate to post larges sections of text, but it might help to read a lot of what comes before the quoted statement in order to fully see this:

(Translated to modern English) “But by the way we have to mark further, that all manner of images and representations are not meant here. For our Lord says expressly that He showed not Himself to his people in any manner except by His voice, and therefore that it is a corruption to make images. If this should be drawn to conclude, that it is not lawful to make any picture at all: it is a misapplication of Moses’s testimony… But when the Holy Scripture says, it is not lawful to shape any resemblance of God, because He hath no body: it extends not so far: for it is otherwise as concerning men. Now then look what we see, that may we represent by picture. And therefore let us see that we apply the texts against the Papists as we ought to do, that we may be armed to prove our case just…Now we see that the Papists have gone about to express God by shapes: therefore it follows that they have marred all Religion. And whereas they allege that there were Cherubims painted upon the veil of the Temple, and that two likewise did cover the Ark: it serves to condemn them [the Papists] the more. When the Papists pretend that men may make any manner of image: What say they? Has not God permitted it? No: but the imagery that was set there, served to put the Jews in mind that they ought to abstain from all counterfeiting of God, insomuch that it was a means to confirm them the better, that it was not lawful for them to represent God’s Majesty, or to make any resemblance thereof. For there was a veil that served to cover the great Sanctuary, and again there were two Cherubims that covered the Ark of the Covenant. To which comes all this, and what is meant by it, but that when the case concerns our going unto God, we must shut our eyes and not approach any closer to Him, than He guides us by His word?”

Erik,

There has been more than a little discussion about Nestorian tendencies in Calvin’s theology. This can be seen in the links I added after the article. What may seem to you a “passing swipe” is still a serious theological accusation that needed to be addressed.

I think you have a good point about a Platonic dualism running through Calvin’s sermon. What troubles me is that if Calvin held to a “material=bad and spiritual=good mentality” as you put it then that implies that Calvin’s theology suffered from a tendency to Gnosticism. Would you agree with that?

With respect to Calvin’s exegesis of the pro-icon Old Testament passages I would have to disagree with your suggestion that Calvin was applying it to the Roman Catholics of his time. That he had in mind the Israelites can be seen in the following excerpt: “but the imagerie that was set there, serued to put the Iewes in minde that they ought to abstaine [30] from all counterfeiting of God.”

Your point about the difference between depicting God the Father and Jesus the Incarnate Word is one that Orthodox Christians would agree with. The question then whether Calvin allowed for the depiction of Jesus Christ. Eric Parker in his Calvinist International article notes that there has been some confusion about where Calvin stood and for that reason this 1555 sermon is valuable for clearing up the matter – Calvin’s unequivocal opposition even to depictions of Jesus Christ can be seen in this phrase: “Beholde, they paint and portray Iesus Christ, who (as wee knowe) is not onely man,* but also God manifested in the flesh. . . .”

It may be that Roman Catholicism of Calvin’s time frequently depicted God the Father in their churches. I don’t know the church architecture of that time period but I know that this is not the case in Orthodox churches. When one visits an Orthodox parish one can expect to see the image of Jesus Christ up front and center. It is here that Calvin’s iconoclasm runs contrary to the historic Christian position as affirmed by the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea AD 787). Calvin and the Reformed churches’ practice of bare walls bears witness to an iconoclastic conviction that runs contrary to both Old Testament biblical architecture, Orthodox architecture, and the Seventh Ecumenical Council.

I tried reading the Old Testament pro-icon passages using your analogy of the parent drinking water, coffee, tea, or soda in front of the child, but ended up confused. If the images of cherubim are like soda permitted to children then why don’t Reformed churches have images on their walls following the pro-icon passages in the Old Testament? Logically speaking at least images of cherubim would be allowed in Reformed churches since Scripture commended that those images. Would you agree with that? The Reformed tradition’s extreme iconoclasm makes me suspect that there is a powerful extra-biblical force at worked in Calvin’s theology (which you suggested earlier). I still that think that Calvin’s reasoning with respect to the pro-icon verses is a non sequitur. To put it bluntly Calvin’s biblical basis for opposing icons doesn’t hold water.

Robert

“…then that implies that Calvin’s theology suffered from a tendency to Gnosticism. Would you agree with that?”

While dualism was an aspect of Gnosticism, I wouldn’t use that term because it carries a lot of other unrelated baggage with it. After all, Calvin wasn’t advocating that the god of the OT was a demiurge separate from the true and ultimate source of all being or that there were different levels of spiritual and physical emanations that those with secret knowledge can become aware of. Calvin never positively referenced Gnostics like Valentinus, but he does just about quote Aristotle as much as he does Augustine in the Institutes. I would limit the critique to the dualism or piestic spiritualism you find in many Protestant circles, and not just the Reformed camp.

“With respect to Calvin’s exegesis of the pro-icon Old Testament passages I would have to disagree with your suggestion that Calvin was applying it to the Roman Catholics of his time. That he had in mind the Israelites can be seen in the following excerpt: “but the imagerie that was set there, serued to put the Iewes in minde that they ought to abstaine [30] from all counterfeiting of God.”

I am actually a little perplexed as to how you can bring Jews back into the term “them” when that whole section of the sermon is about critiquing the RC argument. The reading would be odd in regards to the sentences that come before it because you have him discussing the RCs, inexplicable switching to Jews, going back to the RCs, and then back again to the Jews. For example, let’s plug in the word Jews in the other places and see which makes more sense in the flow of the argument.

“Now we see that the Papists have gone about to express God by shapes: therefore it follows that they [the Jews] have marred all Religion. And whereas they [Jews] allege that there were Cherubims painted upon the veil of the Temple, and that two likewise did cover the Ark: it serves to condemn them [the Jews] the more. When the Papists pretend that men may make any manner of image: What say they [the Jews]? Has not God permitted it? No: but the imagery that was set there, served to put the Jews in mind that they ought to abstain from all counterfeiting of God…”

-or-

“Now we see that the Papists have gone about to express God by shapes: therefore it follows that they [the Papists] have marred all Religion. And whereas they [the Papists] allege that there were Cherubims painted upon the veil of the Temple, and that two likewise did cover the Ark: it serves to condemn them [the Papists] the more. When the Papists pretend that men may make any manner of image: What say they [the Papists]? Has not God permitted it? No: but the imagery that was set there, served to put the Jews in mind that they ought to abstain from all counterfeiting of God…”

“Calvin’s unequivocal opposition even to depictions of Jesus Christ can be seen”

I agree, Calvin would have been against depictions of Jesus. For him the line of thought was that we are forbidden to make images of God, Jesus is God therefore the same rule applies to Him also. I don’t agree with him, because like you mentioned the Incarnation of the person Jesus changed things, but that is what he argues.

“If the images of cherubim are like soda permitted to children then why don’t Reformed churches have images on their walls following the pro-icon passages in the Old Testament? Logically speaking at least images of cherubim would be allowed in Reformed churches since Scripture commended that those images. Would you agree with that?”

For the Reformed, passages like I Kings 6 do not have application for NT churches because they specifically and exclusively dealt with Temple decoration during the Mosaic economy. It’s not that such imagery is commended in worship, rather is was commanded during that time. He was not advocating for using angles and palm trees (or soda and tea) presently, he was just saying that if you’re going cite this passage then all it proves is that you could use this specific imagery. It did not imply that you could make whatever depictions of any person of the Trinity you desired [or drink vodka] like the RCs were/are doing. The Reformed view is that you wouldn’t decorate the walls of an NT place of worship with Cherubims, palm trees, and open flowers anymore then you would sacrifice bulls, play musical instruments, or burn incense. All of these things were shadows tied to the Levitical sacrificial system and pointed to what was to come. Since Christ is the rebuilt Temple, all the Temple activities and decorations no longer apply.

Perhaps you have heard of the Regulative versus Normative principle. The Normative Principle argues that you can use things in worship not expressly forbidden by Scripture, this is what you frequently find in things like Lutheranism and Anglicanism. The Regulative Principle, on the other hand, argues that you can only use what is expressly prescribed or demonstrated by example in the NT. This is what you find in the Reformed camp. So, since using angles and palm trees for decorations are neither prescribed nor cited by example in the NT, they will not do these things. Of course, as I have argued before, they are completely ignoring how NT worship is pictured or exemplified in Revelations.

Speaking of musical instruments, if I King 6 is a pro-icon passage, then why isn’t I Kings 1:39 a pro-musical instrument passage? By this measure EO churches should be blowing trumpets in the church. I am not actually against icons, I just don’t think this passage has anything to do with them, or especially how they are treated within the EO church. After all, there were no images of fellow saints on the Temple walls and the Israelites were not commanded to kiss or reverence the palm tree or angels.

Thank you for giving my post a fair hearing and have a blessed Lenten season.

I wonder if Calvin had a hidden reason for opposing icons and then justified that opposition from scripture. Namely that uneducated untaught people tend to slip into worship rather than reverencing the icons. Having grown up in a country where the state church was Oriental Orthodox that seems very plausible to me. While I think that there is certainly a place for remembering the saints of the past I also think that works that visually portray important theological themes are very appropriate and even more necessary. Themes such as Creation Fall and Redemption. A PCA church that we attended in the past had such a work that represented the Holy Spirit as a dove descending upon and illuminating the word of God. I don’t know if the Orthodox display such works as well as the traditional icons or not.

The depiction of God in the Sistine chapel in the Vatican seems to me to at least border on an illicit depiction of God the Father.

Dawit,

Orthodoxy would agree with you on that. The 1667 Synod of Moscow canonically forbade the depicting of God the Father in icons. That is the short and simple answer. For a longer answer please visit Eric Jobe’s article on Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy.

Robert

Dawit,

I don’t think it matters whether Calvin had a hidden reason for his iconoclasm. What matters is the fact that Calvin who is renowned as a bible expositor mishandled the pro-icon Old Testament passages. This is concerning in light of Protestantism’s claim to be bible-based. I have come to the conclusion that it is the Orthodox position that is truly biblical.

Orthodoxy teaches that we are to venerate (show honor) to the saints but not to worship them. It is important therefore that the priest catechize the people in the parish about the proper way to venerate icons.

I think where you and I differ is that you see icons as having a pedagogical function while the Orthodox see icons as having a sacramental quality. In other words, icons do more than remind us of the saints who have gone before us; they make visible the very real presence of the cloud of witnesses mentioned in Hebrews 12:1. Icons facilitate our fellowship with the saints who have gone before us. That is why when I see an icon of say Apostle Peter I will ask him to join me in praying to Christ.

As far as I know Orthodoxy does not have images of the Holy Spirit as a dove descending upon the Bible. For one thing Orthodox rules for the making of icons does not allow the depicting of the Holy Spirit as a dove unless it relates to specific events like Jesus’ baptism. The Bible is depicted in Orthodox icons. Quite often an icon of Christ will show him holding a book with a bible passage written within. Then the icons of the four Evangelists will show them holding a Gospel book. Icons of saints who held the office of bishops will show them holding a book; this symbolizes their responsibility of holding and expositing Scripture. Icons of saints like John the Forerunner (Baptist) or an Old Testament prophet will show them holding a scroll with words written on the scroll. This assumes literacy on the part of the Christian and is meant to help him or her meditate on Scripture passage.

Robert

Thank you for this blog. After listening to many podcasts Father Hopko and Reading Jobe’s blog, I would simply add that the “He Who Is” is a reference to God’s response to Moses from the burning bush. As an evangelical Protestant, I always heard that name only as “I AM”, which is true. But “He Who Is”, or even “The Existing One” are how we should respond to God calling Himself the “I AM”.

Jesus calls himself “I AM” during his trial before the Sanhedrin.

Just wanted to note that it is not just in Revelation.

Thanks again!

Thank you, Jeff!

Robert