Athanasius the Great summed up the connection between the Incarnation and our salvation in the famous line: God became human, so that we might become god. The doctrine of theosis (deification) sums up the Orthodox understanding of salvation in Christ. It is also the source of friction between Reformed and Orthodox Christians. In this blog posting I will show how the Orthodox understanding of theosis is grounded in Scripture and affirmed in the teachings of the early Church Fathers. In light of the controversial nature of theosis I will be highlighting the Orthodox understanding of theosis through the comparing of paradigm differences between Orthodoxy and the Reformed tradition. I close with a discussion of the practical consequences of the paradigmatic differences.

2 Peter 1:3-4

Many Protestants find the doctrine of theosis dubious despite the fact it is found in Scripture. We read in 2 Peter 1:3-4:

His divine power has given us everything we need for life and godliness through our knowledge of him who called us by his own glory and goodness. Through these he has given us his very great and precious promises, so that through them you may participate in the divine nature and escape the corruption in the world caused by evil desires. (NIV)

This does not mean we participate in God’s essence (ousia). Rather we are transformed into the likeness of Christ through participation in his grace, i.e., divine energies. The footnote commentary in the Orthodox Study Bible for 2 Peter 1:4 reads:

This [Theosis] does not mean we become divine by nature. If we participated in God’s essence, the distinction between God and man would be abolished. What this does mean is that we participate in God’s energy, described by a number of terms in scripture, such as glory, life, love, virtue, and power. We are to become like God by his grace and truly His adopted children, but never becoming God by nature.

The phrase “participate in the divine nature” (NIV) or “partakers of the divine nature” (KJV, OSB) is a translation of: “γένησθε θείας κοινωνοὶ φύσεως.” [Greek NT] The Greek for “participate” or “share” is κοινωνος (koinonos) which has a range of meanings. It has been used with reference to sharing in glory (1 Peter 5:1), sharing in Christ’s suffering (Philippians 3:10), and fellowship in the Holy Spirit (Philippians 2:1). It can have a spiritual/sacramental sense. Participation in a religious service, Christian or otherwise, has definite spiritual consequences. Participation in a pagan sacrifice results in participation with demonic forces (1 Corinthians 10:20) and likewise participation in the Eucharist results in participation in Christ’s body and blood (1 Corinthians 10:16). The emphasis here is on participation, transformation, and experiential change, rather than a judicial declaration of legal status. This distinction is central to the different attitude Orthodox and the Reformed have toward the fullness of salvation in Christ.

Koinonos can connote a sharing in similar circumstances, e.g., “just as you share in our sufferings, so also you share in our comfort” (2 Corinthians 1:7). The word can have relational connotations, e.g. “you became companions of those who were so used” (Hebrews 10:33; KJV); “if you consider me a partner” (Philemon 17; NIV).

The other key word in 2 Peter 1:4 is φυσις (physis). It can mean biological descent/nature: “we who are Jews by nature” (Galatians 2:13; KJV) or spiritual condition: “by nature children of wrath” (Ephesians 2:3; KJV). Paul in Romans uses the word physis in some rather interesting ways. In Romans chapter 2 he points out that there are Gentiles who are “not circumcised physically” (Romans 2:27; NIV) but who “do by nature things required by the law” (Romans 2:14; NIV). The expectation here is that both the outward and inward natures would complement the other. In other words our inner spiritual life ought to be expressed in our outward actions. So likewise our actions should flow from our inner life. And just as significant is the possibility that one’s nature can change, be transformed. In Romans 1:26-27 Paul wrote about “natural desires” (NIV) being “exchanged” (NIV) for unnatural ones. Just as sin results in the alteration of human nature so likewise salvation in Christ calls for a reverse alteration in human nature (cf. Romans 12:2).

While the original Greek koinonos (partaker) has a broad range of meanings, it is restricted by physis (nature). The relational and circumstantial meanings are excluded leaving either sacramental or biological meanings as the most likely options.

The Biblical Basis for Theosis

The biblical basis for theosis begins with the creation account in Genesis. Theosis is implicit in the doctrine of the imago dei: humanity being made in the divine image.

Let us make man in our image, in our likeness, and let them rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air, over the livestock, over all the earth, and over all the creatures that move along the ground. (Genesis 1:26; NIV)

The divine likeness implies our calling to be in communion with God, this makes man unique to the rest of Creation. This goes beyond the legal model which focuses more on our external legal or judicial status and good moral behavior – rather than the transformation of our inner nature. As a result of Adam and Eve’s sin the image of God has become marred in us. In the Incarnation God came to restore the imago dei. Salvation as theosis is based on the restoration of the image of God in us which in turn calls for the restoration of communion with God resulting in a change in human nature, i.e., ontological consequences.

The Apostle Paul in 2 Corinthians describes the Christian life as one of progressive transformation.

And we, who with unveiled faces all reflect the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into this likeness (image) with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit. (2 Corinthians 3:18; NIV)

The reference to the visible transformation of Moses’ appearance in 2 Corinthians 3:13 points to an ontological transformation, not just behavioral and attitudinal changes.

Theosis also has eschatological implications; we find in the Apostle John’s first epistle:

Dear friends, now we are children of God, and what we will be has not yet been made known. But we know that when he appears, we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is. (1 John 3:2-3; NIV; emphasis added)

Theosis finds its culmination in our entering into the life of the Trinity. In John 17 we read:

I have given them the glory that you gave me, that they may be one as we are one. I in them and you in me. May they be brought to complete unity . . . . (John 17:22-23; NIV)

As Christians we are called to be more than good people or even glorified beings like angels, we are called into the fellowship of love that is the Trinity. Thus, the Orthodox understanding of salvation is profoundly Trinitarian in implication.

In Scripture there are several accounts of theosis taking place. Theosis is implied in the account of Jesus walking on water in Matthew 14. Jesus’ walking on water was a sign of his divinity. Just as Jesus walked on water so did Peter implying Peter’s sharing in Jesus’ divinity. Note that Peter did not ask Jesus to grant him the ability to walk on water but that he be allowed to be with Jesus: “Lord, if it’s you tell me to come to you on the water.” (Matthew 14:28; NIV) This is the goal of theosis: union with Christ. Notice also that Peter was able to walk on water so long as he kept his eyes on Jesus, but the moment he became distracted and fearful he began to sink. Jesus reached out his hand and grabbed hold of Peter; this is a sign of God’s grace to us.

Theosis is also found in the Gospel accounts of the Transfiguration where the transfigured Christ speaks to the Old Testament saints Moses and Elijah. In Luke’s account we read that Moses and Elijah “appeared in glorious splendor” and that they talked to Jesus about his impending death (9:31). What happened was that the glory that Jesus had with the Father before the world began (John 17:5) was made manifest to his followers. Jesus’ glory is intrinsic to his nature. This glory attests to Jesus’ divinity. Just as striking is the fact that Moses and Elijah were also clothed in glory. This point to their having been transfigured into glorified beings by God’s grace. Their conversing with Christ points to their having acquired divine wisdom as to God’s will. The contrast between the two Old Testament saints standing up and the three disciples on the ground sleeping shows the progressive nature of Christian discipleship. Right now we are bumbling, fumbling followers of Christ but one day we will reach the state of enlightenment like that of Moses and Elijah. Sainthood is not for the fortunate few but for all Christians. The Orthodox approach to spiritual pedagogy is old school; the bar is set high and those who attain perfection are given due recognition. Orthodox spirituality is not like modern education where you win the prize just for being there. The term “saint” has a real meaning in Orthodoxy when it comes to spiritual advancement.

The Witness of the Church Fathers

In the early fourth century there took place a fierce controversy over whether or not Jesus was truly divine. For the early Christians this was not an abstract doctrinal dispute but one of immense consequence for our salvation. A Protestant would explain the necessity of Christ’s divinity in terms of his bearing the sins of the world. Such an argument is congruent with the penal substitutionary atonement theory but this is not the line of argumentation used by the early church fathers. Instead we read in Athanasius the Great’s On the Incarnation the reason for the Incarnation:

For He was made man that we might be made God; and He manifested Himself by a body that we might receive the idea of the unseen Father; and He endured the insolence of men that we might inherit immortality. (§54; emphasis added)

This was not a novelty by Athanasius. One of the earliest witnesses to theosis is Irenaeus of Lyons in Against Heresies.

. . . our Lord Jesus Christ, who did, through His transcendent love, become what we are, that He might bring us to be even what He is Himself. (AH 5 Preface; emphasis added)

Augustine on Theosis

The early church fathers took care to emphasize that deification is not intrinsic to human nature but a consequence of God’s mercy. Augustine of Hippo makes the critical point that we are deified by grace and not by nature.

See in the same Psalm those to whom he says, “I have said, You are gods, and children of the Highest all; but you shall die like men, and fall like one of the princes.” It is evident then, that He has called men gods, that are deified of His Grace, not born of His Substance. For He does justify, who is just through His own self, and not of another; and He does deify who is God through Himself, not by the partaking of another. But He that justifies does Himself deify, in that by justifying He does make sons of God. “For He has given them power to become the sons of God.” John 1:12 If we have been made sons of God, we have also been made gods: but this is the effect of Grace adopting, not of nature generating. (Augustine Exposition on Psalm 50)

Protestant Mistranslation

Given the catholicity of the doctrine of theosis among the early church fathers, it is puzzling that Protestants would be so reluctant to embrace it.

This bias is so strong as to create a blind spot among its leading patristic scholars. Take for example Gregory Nazianzen’s Oration I in which he asserted:

Let us become like Christ, since Christ became like us. Let us become gods for his sake, since he for our sake became man.

The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (NPNF) series contains a serious mistranslation of the same passage. It reads:

Let us become like Christ, since Christ became like us. Let us become God’s for His sake, since He or ours became Man. (NPNF Second Series Vol. VII, p. 203)

The Greek text in Migne’s Patrologia Graecae Vol. 35 “Oration I – In Sanctum Pascha” (Section 17, p. 358) reads:

“γενωμεθα θεοι δι’ αυτον” (let us become gods for his sake).

It appears that the translators for the NPNF Church Fathers series mistranslated the text due to their Protestant biases! It is surprising and disheartening that there is no footnote offering an alternative reading. Caveat lector!

This leads to the question: Why is the doctrine of theosis so little known among Western Christians? And when they do learn about theosis why are Protestants often hostile to the doctrine of theosis? My suspicion is that what is at work here are differences in theological paradigms.

I. What’s Your Paradigm?

Creator-Creature Distinction

Paradigms provide the framework by which we organize data and exclude data. Because they frame the way we see reality, paradigms are often invisible to us. Because paradigms are not as explicit as doctrine, it takes a bit of detective work to discern the philosophical assumptions that shape a theological tradition.

The Creator-creature distinction that runs through Reformed theology has shaped its theory of knowledge (epistemology) as well as its theory of salvation (soteriology) and its understanding of the Christian life (spiritual formation). Karl Barth in his struggle against Liberalism and natural theology stressed the “infinite qualitative distinction” between the human the divine. It also forms the basis for the Reformed tradition’s radical understanding of grace in salvation, and in absolute categories where man can in no way contribute to his salvation; it is all divine grace. This leads to the principle of monergism which in turn leads to double predestination, that is, God alone determines who will be saved and who will be damned.

This Creator-creature distinction has become more explicit in recent theological discussions on the Internet. Derek Rishmawy in a 2012 blog article wrote:

So, the idea is that because there is a radical gap in reality between God and ourselves–he is necessary, infinite, transcendent, etc. and we are contingent, finite, bound–there is also a radical gap in our knowledge. In the same way that God’s reality is at a higher level than ours and sustains ours, the same is true of our knowledge. (Emphasis added.)

Reformed apologist Michael Horton affirmed the Creator-creature distinction in his criticism of the God of the gaps apologetic strategy:

Accordingly, to the extent that a certain state of affairs can be attributed to natural (human or nonhuman) causes, God is not involved. Again we meet the troubling univocity of being, which fails to recognize the Creator-creature distinction and the analogical character of creation in its relationship to God. (The Christian Faith, p. 338; emphasis added.)

Closer to the topic of theosis is Reformed pastor Steven Wedgeworth’s blog article: “Reforming Deification.” In it Wedgeworth expressed in colorful language his concerns about theosis.

The doctrine of deification (or theosis) is one of those doctrines that, in the words of one esteemed divine, “gives us the willies.”

He continues a little further:

The dangers of the wrong-kind of deification theology should be obvious. Collapsing the Creator-creature distinction, or even just smudging it a little, is seriously bad juju.

The Reformed emphasis on the Creator-creature can be overstated at times. While the Bible does teach the Creator-creature distinction, it also situates humanity at the crux of the Creator-cosmos nexus. In Genesis God climaxes creation with the making of man in his image and conferring on humanity lordship over creation. The Creator-creature paradigm takes an interesting new direction with the Incarnation. The Creator God comes down from heaven and becomes a creature. The Infinite becomes finite. The invisible becomes visible. The intangible becomes tangible. The Eternal enters into history.

“The Unsleeping Eye” Source

The uncontainable Word becomes confined in the Virgin’s womb. The one who made the Milky Way galaxy becomes a babe who suckles at the Theotokos’ breast. The Immortal God dies on the Cross for our salvation.

Mankind doomed to nothingness is rescued by Christ’s dying on the Cross, his third day Resurrection, and his Ascension. Then in the mystery of Pentecost Jesus we are given the Third Person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit.

Did Calvin Follow the Church Fathers on Theosis?

The doctrine of theosis challenges the Reformed theological paradigm because of its explicit endorsement in 2 Peter 1:3-4. This leads to two questions: (1) How did Calvin understand 2 Peter 1:3-4? and (2) Did Calvin in fact believe in theosis? When we look at Institutes 3.25.10 we find something quite close to the Orthodox doctrine of theosis. The only difference is that Calvin seems to understand the conferring of divine glory, power, and righteousness as future events that accompany the resurrection, not as blessings for the current age. Calvin writes:

Indeed, Peter declares that believers are called in this to become partakers of the divine nature [II Peter 1:4]. How is this? Because “he will be . . . glorified in all his saints, and will be marveled at in all who have believed” [II Thess. 1:10]. If the Lord will share his glory, power, and righteousness with the elect—nay, will give himself to be enjoyed by them and, what is more excellent, will somehow make them to become one with himself, let us remember that every sort of happiness is included under this benefit. (Institutes 3.25.10)

Did Calvin affirm theosis? Consider the following:

Let us then mark, that the end of the gospel is, to render us eventually conformable to God, and, if we may so speak, to deify us. (Commentary 2 Peter 1:4)

But as we read on we find Calvin qualifying his earlier statement:

But the word nature is not here essence but quality. The Manicheans formerly dreamt that we are a part of God, and that, after having run the race of life we shall at length revert to our original. There are also at this day fanatics who imagine that we thus pass over into the nature of God, so that his swallows up our nature. (Commentary 2 Peter 1:4)

Thus, Calvin’s concern that theosis not be understood as our sharing in God’s essence is identical to Orthodoxy’s.

So, what did theosis mean for Calvin? He writes:

They [the Apostles] only intended to say that when divested of all the vices of the flesh, we shall be partakers of divine and blessed immortality and glory, so as to be as it were one with God as far as our capacities will allow. (Commentary 2 Peter)

For Calvin theosis consists of our “reverting to our original” state, that is, a return to Adam’s original pre-Fall condition. It appears that Calvin did not give much thought to the possibility that our union with Christ the Second Adam may result in something rather different. In other words, Calvin underestimated the significance of the Incarnation for our salvation. Morna Hooker writes:

If Christ has become what we are in order that we might become what he is, then those things which governed and characterized the old life of alienation from God in Adam no longer apply. It is the old man, i.e. the Adamic existence, which is crucified with Christ, Rom. 6.6 . . . [St. Paul] writes continually to his converts – Be what you are! Man has been recreated, called to be ‘holy’ – he should believe it and behave accordingly. (In Fr. Ted’s blog)

Calvin assumes that theosis is accomplished through a process of the removing of the “vices of the flesh.” This is consistent with the moral or juridical understanding of salvation but to share in immortality and divine glory has ontological implications that Calvin seems reticent to pursue. Prof. J. Todd Billings in a 2005 Harvard Theological Review article examined Calvin’s understanding of deification and found that although Calvin interacted with the early church fathers his understanding of deification is “distinctive” (p. 334). Rather than follow in the hermeneutical tradition of the early church fathers, Calvin here is venturing off in his own direction with a new interpretation. In time this would give rise to a new form of spirituality.

II. What’s Your Paradigm?

Sanctification = Theosis?

Is theosis another name for sanctification? The Protestant doctrine of sanctification does bear a certain resemblance to Orthodoxy’s theosis. Both involve the healing of the effects of sin, are progressive in nature, and culminate at the Second Coming. Another important similarity is that both are the result of the Holy Spirit in the Christian. But there are significant paradigm differences beneath the surface.

The Orthodox understanding of theosis is based on a sacramental worldview in which matter is viewed as capable of conveying divine grace. In this worldview the possibility is there for human beings to become channels of divine grace. As we grow in holiness, as our hearts become cleansed of the passions the life of God pervades our whole being with spillover effects. In contrast, Protestantism understands sanctification as moral transformation or an attitudinal change that leads to behavioral change. This is congruent with its dominant legal approach to salvation. Protestantism not only suspicious of, it implicitly denies the ontological transformation foundational to the Orthodox understanding on theosis.

But the question I have for my Protestant friends is this: Does your understanding of sanctification also allow for ontological transformation? When one reads the history of Protestantism one has to wonder: Where are the saints? Where are the believers whose lives are marked by extraordinary sanctity, steeped in prayer, and transfigured by the Divine Light that shone at Mount Tabor? The prominent personalities in Protestant history tend to be theologians known for their theological insights, e.g., Martin Luther, John Calvin, Ulrich Zwingli, John Wesley, Charles Hodge, Jonathan Edwards, or Karl Barth. Or for their preaching ministries, e.g., George Whitefield, Billy Sunday, Charles Spurgeon, D.L. Moody, Billy Graham; or missionaries, e.g., Hiram Bingham, Adoniram Judson, Samuel Zwemer, Jim Elliot, etc. Implicit in the culture of Protestantism is the priority on theology, preaching, and evangelism, and the downplaying of lives transformed through prayer and ascesis.

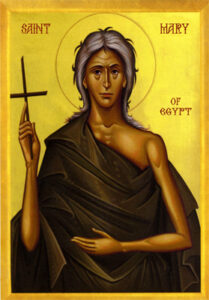

When one reads the history of Orthodoxy one comes across the lives of the saints: Anthony the Great, Mary of Egypt, Seraphim of Sarov, John of Kronstadt, Elder Paisios, John of Shanghai and San Francisco the Wonderworker, Father Arseny, Matushka Olga, etc. — all in the tradition of ‘holy men’ and ‘holy women.’ Ordinary people drawn to these saints because of their sanctity sought the saints’ counsel and their prayers. The saints are empirical proofs of theosis.

The absence of visible saints in Protestantism is something Fr. Stephen Freeman has touched on. He posed the question: “What would Christianity mean if there were no saints?”

What would be the meaning of the Christian gospel if there were no wonderworkers, no people who had been transfigured with the Divine Light, no clairvoyant prophets, no healers, no people who had raised the dead, no ascetics living alone in the deserts for years on end, no beacons of radical, all-forgiving love? (“Saintless Christianity“)

He continues:

The Christian gospel, as recorded in the Scriptures and maintained in Classical Christianity, is replete with the artifacts of holiness – tangible, living examples of transfigured lives – not morally improved but something other. Human beings becoming gods (in the bold language of the early fathers).

He points out that the Protestant Reformation with its rejection of good works and the sacramental worldview resulted in a two story universe in which the world below is separated from the spiritual world of heaven. Many Evangelicals will recognize the unsettling similarity to what the Protestant apologist Francis Schaeffer called the two-story model of modernity. This has resulted in a sort of egalitarian democratization of Christiana spirituality in which all Christians are saints thereby implicitly denying any extraordinary sainthood. However, the New Testament Scriptures speak openly of the full gamut of Christian: from babes in Christ blown about by every whim of doctrine to those of “full age” able to handle strong meat. Just as significant is the fact that the Apostle Paul whom so many Protestants admire as a theologian was a wonder worker (Acts 19:11) and a visionary (2 Corinthians 12:1-4). This flattening of all Christians into one mold has been consequential for Protestant spirituality. The striking absence of visible saints makes one wonder if the emphasis on spiritual equality was worth the price.

In contrast to Protestantism’s two story universe, Irenaeus of Lyons held to the pre-modern one story model of the universe. In his understanding of salvation Irenaeus anticipates a change in Christians like that promised in 2 Peter 13-4. He affirmed the possibility of the flesh of the Christian partaking of the divine life.

But if they are now alive, and if their whole body partakes of life, how can they venture the assertion that the flesh is not qualified to be a partaker of life, when they do confess that they have life at the present moment? It is just as if anybody were to take up a sponge full of water, or a torch on fire, and to declare that the sponge could not possibly partake of the water, or the torch of the fire. (AH 5.3.3; emphasis added)

The tendency in Orthodoxy has been to take the image of the flame quite literally. There is a well known story in Orthodoxy’s mystical tradition:

Abba Lot went to see Abba Joseph and said to him, ‘Abba as far as I can I say my little office, I fast a little, I pray and meditate, I live in peace, and, as far as I can, I purify my thoughts. What else can I do?’ Then the old man stood up and stretched his hands towards heaven. His fingers became like ten lamps of fire and he said to him, ‘If you will, you can become all flame.’

The Goal of Our Salvation

![]() While theosis is ongoing in this life, it finds its fulfillment at the Second Coming of Christ. Is the doctrine of theosis part of the Western theological tradition? I would say that while salvation as theosis is not prominent, it is there.

While theosis is ongoing in this life, it finds its fulfillment at the Second Coming of Christ. Is the doctrine of theosis part of the Western theological tradition? I would say that while salvation as theosis is not prominent, it is there.

One good example of theosis is the conclusion of C.S. Lewis’ sermon “Weight of Glory”:

It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare.

All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilization—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.

Orthodoxy’s teaching on theosis offers a vision of Chrstian discipleship that is much more daunting and challenging than that of Protestantism. What it aspires to is far more exhilarating and exciting than what many Protestants imagine. For inquirers investigating Orthodoxy theosis points to the possibility of Christianity being more than rational theological systems and practical self improvement, it offers access to an enchanted one story universe of incense, chants, ancient hymns, fragrant oils, holy sacraments, miraculous icons, relics, and ordinary people who become extraordinary saints. The ordinary everyday world becomes one charged with possibilities and sacred moments as we say ‘hi’ to possible gods and goddesses during the week. Sunday morning worship is no longer just a half hour sermon with hymns or a relevant message with praise songs, but the moment when heaven strikes earth like lightning and people are swept up into heaven to be with the cherubim and seraphim before the Throne of Glory.

Robert Arakaki

Hey,

So, interesting development of the doctrine here. I’ll have to give it some more thought. I did think you’d be interested in this article by Todd Billings on Calvin and the doctrine of deification. http://www.jtoddbillings.com/Billings-HTR.pdf

Cheers!

D

Derek,

Welcome to the OrthodoxBridge! Thanks for commenting just minutes after the blog posting went up. And thanks for the link.

Robert

Thanks Robert,

Excellent article…which both helps and stirs me to better understand

just what Theosis really IS. Still in my novice-hood phase of Orthodox,

I’m reminded of those awkward sermons on ‘Union with Christ’ where

by the end of the sermon, and real ‘Union’ had suffered the death of a

thousand qualifications…of what ‘it-can’t-possibly-mean’. Thus, nothing.

Lord have mercy. Teach us thy statues.

One theme that deserves perhaps a separate post, maybe on a different

blog is the implication of this:

“This has resulted in a sort of egalitarian democratization of Christian

spirituality in which all Christians are saints thereby implicitly denying

any extraordinary sainthood. However, the New Testament Scriptures

speak openly of the full gamut of Christian: from babes in Christ blown

about by every whim of doctrine to those of “full age” able to handle strong meat…This flattening of all Christians into one mold has been consequen-

tial for Protestant spirituality. The striking absence of visible saints makes

one wonder if the emphasis on spiritual equality was worth the price.”

What price? Surely someone has elucidated on this…the price protestants

and now all the West & World “pays” per their ripple influence on refusing

to “give honor to whom honor is due”. But there’s the baby again in the bath

-water that got thrown out. Refusing to honor/venerated corrupt Popes,

Cardinals and Bishops…eventually lead to the modern West’s love for a new

(much Un-like the decidedly Non-egalitarian Greek democracy) egalitarian-democratization of men, and thus no real Saints, or even exceptional men

worthy of honor and veneration as Scripture clearly does in Heb 11 et al.

With in the void of Holy Men (real Saints) along with no Nobles or Kings

in the civil real to venerate worthy of High-Honor — we gush like school

girls over pop-entertainers, sports stars and hollywood “talent”…which

mostly scorns openly the whole notion of true Honor, depth of holiness,

character and wisdom.

Lord have mercy

I agree with much of what David said. I actually have a longer response, but since Robert mentioned both Rishmway and Wedgeworth, both more competent students of Calvin than I am, I will withhold most of my argument just to see if they will add anything.

*** Refusing to honor/venerated corrupt Popes,

Cardinals and Bishops…eventually lead to the modern West’s love for a new

(much Un-like the decidedly Non-egalitarian Greek democracy) egalitarian-democratization of men, and thus no real Saints, or even exceptional men

worthy of honor and veneration as Scripture clearly does in Heb 11 et al.***

People must understand that whether it is right or not for Reformed to interpret reality in response to corrupt popes, the fact remains that is our history (or story, to wax postmodern) is that history and to ignore it on our part would be less than responsible.

To say that Protestants do not show any honor to those who have gone before is simply false. We err on the other side (see all the “But Calvins said” at Presbytery meetings! LOL). If the problem is that we don’t have a tradition of putting “saint” before a name, so be it. I see that as quibbling over words.

As to the question where are the wonderworkers, I have a further question: if I produced examples would you consider them valid? If not, then why ask the question? If so, we can advance the conversation. So here we go:

John Walsh in the Scottish Reformation was seen with light shining around him. He also raised someone from the dead. Wolfhart Panneberg also saw the divine light.

Richard Cameron, Donald Cargill, and Alexander Peden prophesied (the Humeans at Puritanboard do not like it when I point that out).

Martyn Lloyd-Jones supernaturally confronted demonic elements in the pulpt.

Of course Jacob is right in that the early magisterial protestants did

honor men (one another?) and paid a guarded honor to King(s) to

whom Calvin addressed his Institutes. They even selectively (as we’ve

repeatedly seen) honored some of the Saint, like Augustine, whose

views, as with others they often scorned. Nor is it likely the early re-

formers would warm to the state of egalitarian democracy we see in our

day. Nor has anyone said protestants do not honor any in any way.

Nevertheless, there are problems. In rejecting corrupt Popes et al, the

early Reformers also rejected Augustine and the early Fathers’ episcopal

rule of the Church by Bishops and their appointment of Priest to serve

in their stead…all by the sacrament of laying on of hands by likewise

ordained Bishops and Priests. Indeed, the Reformers would completely

jettison the whole historic idea of Priesthood…for…(wait for it)…a largely

elected Pastorate. It is certain many of them would be shocked at where

this has led (“…i mean, IF pastor/rulers of the Church should be elected/

confirmed by the members of the congregation…then why not magistrates, Kings…And since we are all “equal” in God’s eyes…the modern day homeless, illiterate, drugged peadophile and crack whore has “equal-rights” to elect the

King and Bishop…as anyone.” Or BE elected! [Personhood is ALL that matters

…not character, holiness, Theosis, wisdom…Saintliness]

Back to the issues surrounding Theosis…and the non-egalitarian presence

of exceptional holy men “Saints” — I’m not sure most protestants “get it.”

Our example here is the ‘baby’ thrown out in the bath-water. One cannot

reject the historic place of the Saints or the episcopal/hierarchical rule of

Bishops in the Church…even in favor of “democracy-lite”…without reaping

severe consequences you will not like. It becomes a gateway drug for our

modern progressive egalitarian Church and State. Lord have mercy.

***They even selectively (as we’ve repeatedly seen) honored some of the Saint, like Augustine, whose views, as with others they often scorned. ***

Part of the difficulty here is that there weren’t critical apparati of the fathers until quite recently. Calvin knew that Augustine said some good things, yet he also knew that a lot of late medieval guys forged stuff under fathers’ names (Pseudo-Isodore et al). Even your Photios was aware of this problem which is why he really couldn’t give a final evaluation of Augustine.

***Nevertheless, there are problems. In rejecting corrupt Popes et al, the

early Reformers also rejected Augustine and the early Fathers’ episcopal

rule of the Church by Bishops and their appointment of Priest to serve

in their stead…all by the sacrament of laying on of hands by likewise

ordained Bishops and Priests.***

That would be news to Bucer and Hooker (since Hooker wrote a book defending bishops!). I have no fundamental problems with laying on of hands, provided by it we don’t mean that “grace” (or being) is imparted to those lower on the scale of being.

*** Indeed, the Reformers would completely jettison the whole historic idea of Priesthood…for…(wait for it)…a largely elected Pastorate.***

But…Hooker? An elected ministry predates the Reformers, as anyone who’s read the Investiture controversy knows. On the other hand, communions like Lutheranism did not go to an elected pastorate until later in the game.

***It is certain many of them would be shocked at where this has led (“…i mean, IF pastor/rulers of the Church should be elected/ confirmed by the members of the congregation…then why not magistrates, Kings…***

And…? I am not sure what your main argument is. The largely “r”epublican bent of later Reformers is more of a reaction (warranted) against the depraved Stuarts. By contrast, the greatest monarch of the last 700 years, Gustavus Adolphus, was a Lutheran who singlehandedly stopped the Inquisition from overruning Europe.

Folks,

Let’s remember to keep the conversation focused on the main thesis of the article: theosis as the goal of our salvation in Christ. Jacob, I appreciate your initial points about miracle working Protestant saints but let’s not get caught up in a detailed debate about ordination of church leaders. Save that for a one-on-one coffee talk with David. You don’t have to respond to everything David writes, especially when you admit you don’t see his main point. Just ask him how it relates to the main point of the article. Sometimes restraint goes a long way in advancing the conversation. Everyone who joins the comment thread has an obligation to maintain the coherence of the comment thread.

Robert

Fair enough. I didn’t want to get in an ordination debate and I certainly won’t pursue that route. I brought up Protestant wonderworkers because I thought the article specifically asked where they were.

Thanks Robert for reeling us in. I noted up front this was a ripple “implication” that might be best addressed in another blog…and had intended to let it drop. My point was only the undeniable connection between Theosis…to Ecclesiastical & Civil realms — both hierarchical and non-egalitarian, as I suspect Jacob will agree at least in part. Lord have mercy on us all.

“This flattening of all Christians into one mold has been consequential for Protestant spirituality.”

This is very true. The Bible is replete with references and examples of how God responds differently to the prayers of men and women, depending of their personal holiness and seeking after God. James 5:16 tells us “The effective, fervent prayer of a righteous man avails much”. We see the same in 2 Chronicles: “if My people who are called by My name will humble themselves, and pray and seek My face, and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin and heal their land.” 2 Chronicles 7:14

The idea that some people have more powerful prayers than others goes against this Protestant notion of the democratisation of believers. Yet it is biblical and is manifested in the Church in the petitions of intercession of Saints and Desert Fathers, both those living and those who belong to the “cloud of witnesses”.

The Protestant churches miss out on the efficacy of powerful intercessors by their not seeking out saints.

It might be interesting to do a compare and contrast between Orthodox wonderworking Saints and the kind of Protestant figures Jacob mentions. It’s not as if we Orthodox don’t expect to see any manifestation of the Holy Spirit whatsoever outside the Church, but outside the Church, these many times seem to be extraordinary and isolated events even in the life of a particular believer, much less in a particular Christian tradition as a whole, and I don’t see any examples or claims of such being an ongoing part of the life a particular Saint or of the Church from one generation to the next (modern Pentecostal claims notwithstanding) in the way we see in Orthodoxy.

In remarking on the consequences an embrace of the “two-storey” mindset, Fr. Stephen Freeman makes a rather astute observation in his book, Everywhere Present. He writes:

“Whenever God and all things associated with Him are exiled from daily life–whenever words such as ‘normal’ and ‘ordinary’ are used to describe the world without God–it is a foregone conclusion that God and all things associated with him will become increasingly irrelevant and foreign to the lives we live. . . .

“This odor of doubt surrounding most things religious in our culture creates a market for miracles, stories of near-death experiences (‘there-and-back-again’), and an undue interest in paranormal phenomena. A friend of mine, a monk from Belarus, once tellingly commented, ‘You Americans! You talk about miracles like you don’t believe in God!’ The doubt of the first-floor Christian is not quite the same thing as unbelief, but it is a powerful reflection of the distance at which God sits. . . . .”

The attitude toward the “supernatural” manifestations of the Holy Spirit’s presence in the Protestant world is quite varied also (unlike in the Orthodox tradition where there is a rather uniform attitude and expectation about such things). Having spent a little over a decade in the world of Pentecostalism (a couple of those on its mission field), I can attest this vacuum of an experiential sense of God’s presence in the daily life of the Church that affects the lives of so many modern Christians, unfortunately, can open believers up to all sorts of ridiculous claims and practices that have nothing to do with real healing and holiness as these have been manifest in the lives of the Saints of the Orthodox Church. Within Orthodoxy, there is balance–everything is in its place. In the Protestant world, historically it seems like there are often pendulum swings of enthusiasm and excess followed by dry intellectualism which find their places today in the emphases of different traditions.

My only problem with Freeman’s comment is that if pushed too hard it simply reduces to all “chain of being” ontology.

I don’t recognize the terminology of “chain of being” ontology. Perhaps you have elaborated what you understand by this at your site. In any event, I suspect you misunderstand aspects of this Orthodox use of the terms of “being” vs. “non-being” to describe the nature of spiritual life vs. sin/death as dynamics at work in the world and in the human soul. Fr. Stephen does spend quite a bit of time (often in the comments threads) trying to make this clearer for our unaccustomed “ears.” I don’t know how much you have read (if any) at his site to try to get a sense of where he is coming from on this. Perhaps, also, Robert may have a bit more of a sense of where you are coming from as well as what is the Orthodox understanding here. I’m out of my league in discussing this with you, but I can say what Fr. Stephen writes about this makes a lot of sense to me.

Hi Robert,

I just checked my copy of NPNF volume VII for that quote from Gregory of Nazianzus. It is in his Oration on Easter and His Reluctance (Oration 1 in the collection of Gregory’s works). It is just as you said ‘…become God’s for His sake… ‘ instead of ‘…become gods for His sake… ‘

I’ve always found the footnotes in the NPNFs to be over the top but this mistranslation has me wondering. How deliberate was this translation? It would be easy for an apostrophe to sneak in during the editorial process.

While I will continue to read and use the NPNFs I will now do so with even more caution.

Stefano,

I’m glad you read NPNF for yourself. As you know, there’s all kind of stuff out there on the Internet. This means we need to exercise caution as we surf the Internet. Finding the truth requires careful consideration of the evidence. I try hard to make this blog evidence driven.

As I was doing research for this blog posting I found two conflicting quote references to Gregory of Nazianzus. I was fortunate to know about the Migne collection being available online and I’m fortunate I can read Greek. So you can imagine surprise when I read Migne and realized that the NPNF passage was in fact a mistranslation. I’m hoping that there will be engagement between Orthodox and Protestant scholars on this particular passage. This kind of discussion will be valuable in advancing the Orthodox-Reformed dialogue.

Robert

Excellent and thought provoking thoughts. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you Phillip!

Perhaps the notion of Formal Cause could help us understand something about Theosis that we don’t already understand–at least, that *I* don’t already understand. Are you aware of anyone, person or group, that has done serious thinking on how theosis could be construed as participating in God as Formal Cause, via worship? If you know of anyone working on this, or who has (even as ordinary a resource as Thomas?), please let me know.

Bruce,

I suggest you post this request on FaceBook. I know of several FB groups involving Reformed and Orthodox Christians in dialogue.

Robert

Robert,

I just found this post. If you are able to answer a few of loosely related questions, I would be grateful.

1) When you speak of the ontological implications of theosis, what do you mean? Ontological restoration, or a qualitatively different ontology of glorified humanity?

2) Is the distinction between Creator and creature upheld in theosis? I am not so much concerned about what the Reformers have to say on the distinction, since I am quite familiar with these. However, Fathers like Irenaeus, for example, dictates Deus facit, homo fit (God makes, man is made), how does this work within the Orthodox paradigm for theosis?

3) You point out the problem of the Protestant (Schaff?) translation of the Ante and Post-Nicene Fathers. Are there English translations of the Fathers that you are more inclined to recommend to a non Greek/Latin reader?

Jedidiah,

Good questions! With respect to question (1) I would venture that theosis probably involves both restoration and our transformation into a glorified humanity. Keep in mind that our first parents Adam and Eve were creatures of glory and that they were stripped of that original glory as a result of the Fall. We also need to keep in mind that Adam and Eve were like infants on the way to maturity and perfection until they took a wrong turn. It seems to me that Adam and Eve’s eventual perfection would end up in the condition of the future glorified humanity Paul wrote about in Romans 8.

With respect to question (2), I found this in Kallistos (Timothy) Ware’s “The Orthodox Church” (p. 232) which quotes Vladimir Lossky: “We remain creatures while becoming god by grace, as Christ remained God when becoming man by the Incarnation.” A good example of theosis is the account of Christ’s transfiguration on Mount Tabor. Moses and Elijah in their deified state were able to converse with Christ, while the disciples Peter, James, and John, were asleep. Peter, James, and John are examples of our present state while Moses and Elijah are examples of our future state.

With respect to question (3), I would say that the Church Fathers series initiated by Schaff are probably the most accessible to readers today. There is something comparable by New Advent which is Roman Catholic. I still think highly of Schaff’s ANF and NPNF series. Mistranslations come with the territory for translated work. My recommendation is that people not worry about mistranslation and be open to exploring the rich heritage we have in the Church Fathers.

Robert