In a recent blog posting Pastor John Armstrong wrote about his paradigm shift on the Incarnation. I found his article very helpful for illustrating the different ways Protestants and Orthodox approach the Incarnation. Armstrong wrote:

For now I have been thinking about how the Orthodox Church has a doctrine of salvation that includes the whole world, or the teaching of cosmology. Simply put the Orthodox do not treat the incarnation, the cross, and resurrection as separate events when explaining our salvation. I have concluded that this approach has to be correct because it fills in some holes in our Western way of thinking that is too individualistic. It also challenges the tendency in the West to center on legal categories when it seeks to explain the cross and God’s love. (Emphasis added.)

The Incarnation is one area where Reformed and Orthodox Christians frequently talk past each other not being fully aware of the differences separating them. When I became Orthodox I criticized some of my friends for not taking the Incarnation seriously, and some felt insulted by this. As bible believing Evangelicals they strongly believed in the Incarnation, so how could I accuse them of not taking the Incarnation seriously? I felt frustrated because I did know quite how to explain the reasons for my criticism. Over time I became aware that the differences were paradigmatic, that is, the role/function of the Incarnation in the Protestant theological system is quite different from its place in Orthodoxy.

Evangelicals do believe in the historicity of the Incarnation, but theologically they view it as a preliminary step, secondary to the big event of Christ’s atoning death on the Cross. For many Protestants all salvation is assumed in Christ’s death. Humanity’s chief problem was solved; the sinless Son of God took on our guilt on the Cross and if we believe in Christ our sins will be forgiven — our legal standing before God will be restored (righteousness) thereby entitling us to certain benefits in the kingdom of God, e.g., eternal life, resurrected bodies, a place in heaven, the right to ask God for things (intercessory prayer) etc.

But for Orthodoxy the Incarnation is just as significant for our salvation as Christ’s dying on the Cross, as well as his third day resurrection. We are saved by the person of Jesus Christ, not just by that one thing he did on the Cross. In baptism we are united to Christ’s death and his resurrection, we receive the Holy Spirit and are incorporated into his Body (the Church). We cease to be autonomous beings and now live in the context of the liturgical and sacramental life of the Church. In the course of the liturgical cycle of the major feast days of the Orthodox Church we participate in the mysteries of Christ’s Incarnation, his Nativity, his presentation in the Temple, his Baptism in the River Jordan, his Transfiguration, his ascent to Jerusalem, his entry into Jerusalem, his death on the Cross, his Resurrection, and his Ascension. In the Incarnation the Eternal entered into history. The life of Christ recounted in the Gospels is not a sequence of events but transcends the limitations of chronological time. Through the Church’s liturgical life we participate in the baptism at the River Jordan or Christ’s Transfiguration on Mount Tabor as if we were there. The Orthodox Holy Week services are more than Sunday School lessons. In these services we participate in Christ’s last week on earth. This is ontologically possible because of the Incarnation. We are no longer separated by two thousand years of time, because we are in the Body of Christ, the Church.

Despite the differences in theological paradigms it appears the lines of communication are becoming clearer between Reformed and Orthodox Christians. We are no longer talking past each other. Below is an excerpt from a recent Facebook thread that I participated in (emphasis added). I wrote:

Charles, In Protestantism the focus is on an event – Christ’s dying on the cross for our sins. In Orthodoxy the focus is on a Person and the life He lived — the arc of Christ’s life beginning with his taking on human nature, his birth, his growing up, his ministry and teachings, his death on the Cross, his third day resurrection, his ascension into heaven, his sending the Holy Spirit, and his glorious Second Coming. Jesus is the Second Adam who recapitulated our life. When I was a Protestant I couldn’t quite figure out how all the events fit together. It seemed that the Cross was the essential thing for our salvation but all the other things weren’t as important. With Orthodoxy’s emphasis on the Incarnation — the God-Man entering into human history — all the pieces fit together into one coherent picture. –Robert

Charles replied:

Robert, I agree that Protestantism in general can focus on the cross a little too much. That is why I am glad that I am Reformed =D. I agree that the cross isn’t the only component to the gospel–it is crucial to also take into account the estates (humiliation and exaltation) and offices (prophet, priest, and king) of Christ. The period between the Incarnation and the Crucifixion would signify the estate of humiliation, and the period between Resurrection, Ascension, Intercession, and the 2nd Coming would be the estate of exaltation. So in essence, I guess we would disagree about the role of the Incarnation–to the Eastern Orthodox, it seems that it is the core. For me (and Reformed theology), it seems that the Incarnation is merely a step in the process for eschatological inauguration, fulfillment, and realization. -Charles

So while Charles and I agreed to disagree, a genuine dialogue did take place between the Reformed and Orthodox traditions. This is a small but important first step in Reformed-Orthodox dialogue.

Paradigm Shifting

My paradigm shift began when I did some reflecting on the Nicene Creed. I noticed that the particular location of the word “salvation” in the Creed. The Nicene Creed states: “For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and was made man. . . .” The Creed then proceeds to recount Christ’s suffering, his death on the Cross, his third day resurrection, his ascension to heaven, and his future return in glory. I thought to myself that if a Protestant were to write the Nicene Creed they would state that Christ came down from heaven, took on human flesh, then died on the Cross for our salvation etc. As I followed the grammatical structure of the Nicene Creed I began to see that our salvation stems from a whole series of things that Jesus Christ did as the God-Man. Reciting the Nicene Creed Sunday after Sunday had a powerful influence on my thinking. It shook me out of my more narrow Protestant thinking and reoriented me to the holistic thinking of the early Church.

Pastor Armstrong’s “it fills in some holes in our Western way of thinking” describes well what happens when one encounters a better paradigm. One does not reject the earlier data as one experience a better and more comprehensive understanding of how the data relates to other data. I found in the Nicene Creed a theological paradigm at odds with an often exclusive Protestant penal substitutionary model of salvation. Salvation history is more than just the singular event of the crucifixion; salvation encompasses God’s sovereign mercy in the flow of human history culminating in the coming of the God-Man Jesus Christ who through the Incarnation entered into the flow of human history.

Doing Theology Through Worship

One thing that struck me on my journey to Orthodoxy was how much of its theology is done through worship. In the West much of theology is done through books and sermons; in Orthodoxy much of its theology is articulated in its liturgical services. Much of what I learned about the Orthodox understanding of the Incarnation came, not from a book, as from Orthodox hymnography. Liturgical worship in Orthodoxy has a theological function unparalleled to that in the Reformed tradition. There seems to be nothing similar to it in the Reformed tradition. I learned much of my Reformed theology from books, not hymns. It is as if “Reformed hymnography” is an oxymoron.

This is why inquiring Protestants will be invited to attend the Orthodox services. This is not about a “warming of the heart” experience that “confirms” a religion as some cults would claim. We invite people to the services because one simply cannot grasp the fullness of the Orthodox Faith by just reading theological books. One or two visits will not suffice; it takes several months of faithful attendance before one begins to grasp how Orthodoxy does theology. One does not become an expert on Orthodoxy after attending a few services. It takes time to absorb all that’s goes on during an Orthodox service. So, you will be asked, “Come and See.” It is in the Liturgy that one sees Orthodox theology in action.

In the liturgical hymns and prayers of the Church we learn about the significance of the Incarnation. One frequent theme is the paradox of the Incarnation, e.g., the Infinite God becoming a finite human being or the unapproachable Judge approaching sinful humanity in humble mercy. We find this paradox in the prayer below sung during the fifth week of Lent:

The angelic nature was wholly surprised at the great act of thine Incarnation; at beholding the Unapproachable (in that he is God) becoming Man approachable by all, walking among us, and hearing from all, Alleluia. (Triodion, Saturday of the Fifth Week, Nassar p. 11; underscore added)

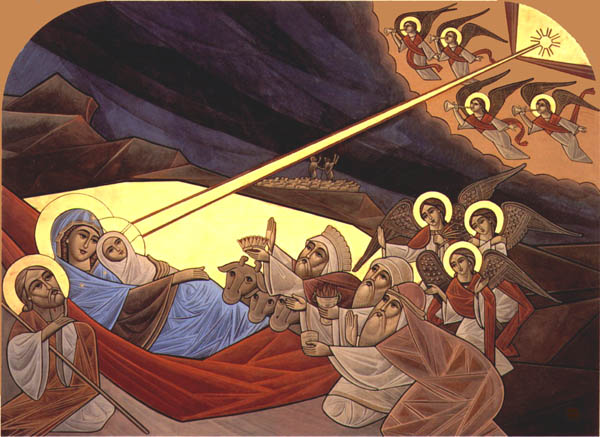

Christmas is a natural occasion for celebrating Christ’s two-fold nature. In the example below we see the paradox of the invisible God becoming visible for our salvation, and the infinite Son becoming confined to the womb of a Virgin.

Today the invisible Nature doth unite with mankind from the Virgin. Today the boundless Essence is wrapped in swaddling clothes in Bethlehem. Today God doth guide the Magi by the star to worship, indicating beforehand his three-day Burial by the offerings of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Wherefore, we sing to him saying, O Christ God, who wast incarnate of the Virgin, save our souls. (Menaion – Sunday after Christmas, Nassar, p. 412; underscore added)

Another example of the Incarnation’s importance to Orthodoxy can be seen in the service for Christ’s circumcision. Here the Incarnation is linked to Christ as the perfect Jew who fulfilled the Law and in so doing paved the way for the New Covenant.

O most compassionate Lord, while yet God after thine essence, thou didst take human likeness without transubstantiation; and having fulfilled the law thou didst accept willingly circumcision in the flesh, that thou mightest annul the shadowy signs and remove the veil of our passions. Glory to thy goodness, glory to thy compassion, glory to thine ineffable condescension, O Word. (Menaion – The Circumcision, Nassar p. 423; underscore added).

Orthodox hymnography interweaves the Incarnation into Palm Sunday in an absolutely stunning way I never imagined when I was a Protestant. In the Palm Sunday hymn the Incarnation is subtly introduced by means of comparing the exalted heavenly throne with the lowly earthly throne. There is nothing in Protestant theology that would disallow this blending but it is striking that the theme of the Incarnation is not usually heard when Protestants celebrate Palm Sunday.

The Word of God the Father, the Son who is coeternal with him, whose throne is heaven and whose footstool is the earth, hath today humbled himself, coming to Bethany on a dumb ass. (Menaion – Palm Sunday, Nassar pp. 733-734)

Orthodoxy’s liturgical cycle can have a tremendous formative influence on one’s theological thinking. Pastors frequently lament how hardly anyone remembers their sermons. This is not so much the pastor’s fault as the inherent limitations of didactic teaching. We are not brains on a stick but embodied souls; as creatures made in God’s image we need to be engaged with our whole being in our worship. This is the advantage of liturgical worship. After hearing the hymns about the Incarnation sung repeatedly the theology gets engraved both consciously and subconsciously on our souls. All this is complemented by icons, incense, prostrations, and Scripture readings which interweave with each other to form the fabric of Orthodox worship.

Conclusion

Both Protestants and Orthodox affirm the historicity of the Incarnation. (Protestant Liberals who reject the historicity of the Incarnation have left the historic Christian Faith.) This has resulted in two quite different understandings of the Christian faith. First, with respect to God’s saving grace in Christ Protestants tend to view salvation as a point in time, an event — Christ’s death on the Cross; Orthodoxy on the other hand views salvation as an arc – Christ’s descent from heaven, his life and death, and his ascent to heaven. Second, with respect to salvation Protestants tend to define it as accepting a message about what Christ has done for us on the Cross. Among Evangelicals it has been reduced to “making a decision” to accept Christ. Orthodoxy views salvation as union with Christ. In Orthodoxy accepting Christ as Lord and Savior means undergoing baptism. Life in union with Christ means life in the Church, the body of Christ. The Incarnation means the embodiment of divine grace: in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, the Church, the sacraments, the Eucharist, etc. There is a certain subjectivity in the Protestant understanding of the sacraments as an outward sign of an inward grace. But the fact is even in the presence of an unbeliever the sacraments of the Orthodox Church are vehicles of divine grace in a very real sense. The efficacy of the sacraments is the result of the Church being the body of Christ.

Pastor Armstrong’s recent paradigm shift on the Incarnation is significant. It will likely have a ripple effect on his Reformed theology. He noted taking the Incarnation seriously opens the way to understanding salvation as union with Christ and in turn to the real presence in the Eucharist. These two themes are prominent in Mercersburg theology. While not as prominent as other theological schools, Mercersburg Theology probably represents the strongest point of contact between Reformed Protestantism and the early Church. I anticipate that Pastor Armstrong’s paradigm shift will stimulate further Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. Paradigm shifts can have unexpected cascading effects. In my case and other Reformed Christians Mercersburg theology became a bridge that took us to the early Church then eventually into the Orthodox Church. It will be interesting to see how Pastor Armstrong’s theological paradigm shift will unfold over time.

Pastor Armstrong’s recent paradigm shift on the Incarnation is significant. It will likely have a ripple effect on his Reformed theology. He noted taking the Incarnation seriously opens the way to understanding salvation as union with Christ and in turn to the real presence in the Eucharist. These two themes are prominent in Mercersburg theology. While not as prominent as other theological schools, Mercersburg Theology probably represents the strongest point of contact between Reformed Protestantism and the early Church. I anticipate that Pastor Armstrong’s paradigm shift will stimulate further Reformed-Orthodox dialogue. Paradigm shifts can have unexpected cascading effects. In my case and other Reformed Christians Mercersburg theology became a bridge that took us to the early Church then eventually into the Orthodox Church. It will be interesting to see how Pastor Armstrong’s theological paradigm shift will unfold over time.

Robert Arakaki

See also my earlier article: “Do Protestants Take the Incarnation Seriously?”

References

Mother Mary and Kallistos Ware. 2002. Festal Menaion. St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press.

Seraphim Nassar. 1993. Divine Prayers and Services of the Catholic Orthodox Church of Christ. Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese. Englewood, New Jersey.

Another engaging and informative article Robert! While I was still in the PCA – before becoming an Orthodox catechumen – this difference in emphasis and importance on the the salvific role of the Incarnation (and whole life of Christ) was a realization, which further confirmed the truth of Orthodoxy to me personally – to the exclusion of the western “christianities”. I especially liked your observation about the wording in the Nicene Creed: “Who for us and for our salvation came down from heaven and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary.”

Thank you James!

Robert

Thank you for including a link to my blog in this thought-provoking article.

Thank you John! I enjoy reading your blog “The Modern Monastic Order of Saint Simon of Cyrene.”

Robert

“In the course of the liturgical cycle of the major feast days of the Orthodox Church we participate in the mysteries of Christ’s Incarnation…”

Our priest rightly points out that this concept of “anamnesis” was also a Jewish way of thinking. Specifically, when celebrating the Passover, the Jews saw themselves as participating in the original event, an event that, for them, continues in the eschaton.

And for us Orthodox, there is one Eucharist celebration, that we participate every Divine Liturgy.

Amen!

Thanks again Robert…excellent article. Your exhortations about attending Orthodox Divine Liturgies are crucial. For decades I’ve heard (and have thought I “got it”) that theology is more caught than taught…and that we obey…to understand. But the pedigogical effects of the past 8 months as an official Catechumem in the Divine Liturgy have been wonderful. While I’d tasted Orthodoxy well enough to apprehend its sweetness…what I didn’t know (and still likely don’t fully!) is hard to explain.

So you lurking inquirers…make a point to attend at lest a dozen or so Divine Liturgies (all in a row if you can) before you think you understand. You won’t be sorry. It’s a rich and wonderful world you can’t imagine.

As for the Incarnation’s significance…it also challenged my post-fall calvinistic anthropolgy. That Christ took His flesh of fallen humanity from the womb of the blessed Virgin…without becoming totally depraved…was arresting.

david

Just a thought:

I’ve never met anyone, Romanist or Protestant, who admits to short-changing the Incarnation. I was thinking about this the other day. The denouement of the biblical narrative is neither the Incarnation nor even the Cross, but the Resurrection (and possibly, the sessional reign or premillennial return). Therefore, to be faithful to the “flow” of biblical of the biblical narrative, emphasis should be on these other events.

Just because they don’t admit to it, doesn’t mean that they don’t. I’m sure Nestorians and Arians of old didn’t think they were denying anything crucial, theologically speaking, about Jesus Christ, but they were. I’ve heard it time and time again that I, as a non-Reformed Christian, borderline deny God’s sovereignty all-together. According to their own paradigm, I probably do, though I wouldn’t say that I do, at least, according to Orthodox theology. Seems like the same sort of thing regarding the incarnation.

John

So true about the Reformed saying that those who are not Reformed deny God’s sovereignty!

Well Jacob, let me be your first! :-). Before I became Orthodox

I admit (unintentionally and mostly in ignorance) to “short-

chang[ing] the Incarnation.” I did this at least by neglect and

by over-emphasizing the Cross. I did this by not apprehending

the full significance of God taking on human flesh…and by my

teachers not laying it out as fully as the Orthodox have. I also

suspect thousands of Orthodox “converts” would confess similar

things as I have here. Indeed, one might even argue that Pastor

Armstrong admits to as much, as the theme of his article, which

was the occasion for this subsequent article? This says nothing

whatsoever as to the absolute necessity of the Crucifixion or

Resurrection.

The same boat for me, David. I had never realized the gap and had really “spiritualized” quite a few aspects of Christ’s coming. His redemption of mankind was limited to only substitutionary atonement under the penal theory. The Incarnation was only important because it brought Christ to the Cross and showed that God had accepted His sacrifice by resurrecting Him. Jesus’ whole life and ministry were nice bits and certainly revealed morality, but the concept of redeeming all things and taking them into Himself was foreign. But the broader construct of the Atonement was foreign. I fully admit that I saw it as man needing to be saved from a vengeful God that also happened to be loving too – I never put two and two together that God freely forgives and needs no payment for it; that death is a consequence of our actions that separate us from God due to our denial of being that which we were made to be.

I was a Reformed Protestant who did not perceive the fullness of the Incarnation. I certainly took the Cross seriously, but things not related to Jesus’ Passion were secondary and less meaningful. Exploring Orthodoxy opened that all up and has revealed the fullness of the Incarnation.

The only question I have regarding the idea that God needs no payment is the question of why blood had to be shed. Hebrews states that “without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness.” Do we leave that phrase as it is or do we try to understand the why? Do the Orthodox have a why?

Actually, I make tentative steps along the road to Orthodoxy, I’d like to hear an answer to this one as well. It’s a bit of a stumbling block in discussions with my wife who is willing to follow, but not nearly as far along as I am.

OK, I can finally say I sparked one of the long discussions for which I have enjoyed here for a couple of years. It’s like a Lone Ranger moment: “Our work here is done, Tonto.” 🙂

Seriously though, this is all interesting, but I am still left with a bit of a conundrum. On the one hand, I find the Orthodox arguments against the notion of an infinitely offended and therefore wrathful God whose honor (justice?) must be satisified by an infinite punishment etc. to be compelling. When I first read Fr. Bernstein’s discussion of this in his book “Surprised by Christ” I was struck by it. It brought into stark relief several thoughts that had floated on the back of my “Bible believing” Bible Church going mind for several years. Its realtively unsophisticated reasoning was then butressed by all the usual suspects (Carleton, Romanides, et al.) On the other hand, we have language that at first glance seems to support some sort of propitiative economy. Like countless others, I often find the “plain meaning” is more a function of unspoken hermaneutical assumptions, but some of this can occassionally sound like a Calvinist wishing away passages that indicate free will.

This is less about inappropriately “philosophical” theology and more about practical daily implications. Answering your children’s questions, answering your wife’s objections, etc. is extremely difficult when you worship in the millieu of a fundamentalist Bible church steeped in a Sola Scriptura epistemology.

Anyway, this is a bit rambling. Mostly it’s frustration. The fact that I can no longer affirm key doctrinal statements of a church congregation that has been our home for seven years or of a form of Christianity (“non-denominational”, “Bible Church” Protestantism) is starting to be a serious strain on my family and on me.

Eric,

You might want to check out these two articles on the death of Christ as sacrifice, from Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy:

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxyandheterodoxy/2014/02/24/the-death-of-jesus-as-sacrifice-an-orthodox-reading-of-isaiah-53-and-romans-325/

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxyandheterodoxy/2014/02/25/the-death-of-jesus-as-sacrifice-part-2-the-atonement-and-justification/

I’m not sure if they will exhaust your answer but it might be a good place to start. You might even comment in order to get the specifics your looking for. I hope it helps.

John

Read the whole context, not just that one verse.

1) It is speaking contextually of the Old Covenant.

2) It says “almost all”.

3) There are a myriad of examples (I can dig them up if you like) of atonement being made (in many cases by non-Jews, but this applies to the Jews in some cases) per God’s command that are not bloody at all!

There’s more to be said though. This was a troubling verse for me for a while.

John

καὶ σχεδὸν ἐν αἵματι πάντα καθαρίζεται κατὰ τὸν νόμον καὶ χωρὶς αἱματεκχυσίας οὐ γίνεται ἄφεσις. “and almost with blood all things are cleansed according to the law, and apart from bloodshed forgiveness does not happen.”

It could be argued, perhaps that σχεδὸν refers both to the cleansing and the forgiveness, but I would have to consider it more contextually. Certainly the meaning could have been stated more clearly one direction or the other.

Prometheus,

I’m not sure it’s accurate to say that Orthodoxy teaches that “God needs no payment” as you put it. It’s possible that some Orthodox Christians have taken that extreme position but can you provide some references to a church father, conciliar teaching, or liturgical text that teaches this? When I became Orthodox I did not stop believing in Christ’s atoning death on the Cross. How can I when at every Eucharist I hear the priest recites the Words of Institution where Christ says that his body and blood are offered for the forgiveness of sins? Or am I missing your point? When I became Orthodox my understanding of salvation became bigger. I continued to believe in Christ’s atoning death but I also factored in his resurrection from the grave and the fact that through baptism I am ontologically united to Christ. This ontological union with Christ became possible when the uncreated Word of the Father took on created flesh from the Virgin Mary. This is something that would have been alien to my thinking when I was a Reformed Christian.

Robert

robertar,

if you haven’t already done so, read N.T. Wright’s “The New Testament and the People of God.” He lays it out what “the forgiveness of sins” meant to the Jews who were listening to Jesus and hearing/reading St Paul. Wright’s interpretation of things overlapped the Orthodox interpretation so closely that he basically led me to the doors of the Orthodox Church – couldn’t lead me in but brought me right close 🙂

Dana

Payment is not made to God, it is made to Death. Ἄφεσις is used in Attic Greek as relating to the discharge of a bond or forgiveness of a debt. That debt is owed to death – the state we entered into when we rejected God’s purpose and decided to set ourselves up as gods under our own power. The language used in Hebrew is debt language, but it’s important to understand what holds us in debt. My own understanding formerly was that we owed a debt to God. We do not. The debt is owed to Death and Hades, which Jesus Christ destroyed from the inside. That is why “He descended into Hell” is an important part of the Apostles’ Creed; it is Christ destroying Death. It’s confused in English because we generally equate Hell to Gehenna when it is supposed to be equated to Hades, but that misunderstanding began in the Latin translations and has continued (and likely led to the creation of Purgatory in Catholicism).

So there is a payment made, but not in the legal Anselmian sense. It is a payment of a debt owed to Death. Mankind’s nature was wounded and contorted in The Fall. We could not die, but we could be unnaturally rent from our bodies to dwell in a lonely and fallen state for eternity, becoming smaller and smaller as the distance from the Source Of Life grew greater and greater. From the Anaphora of St. Basil:

“He lived in this world and gave us commandments for salvation. He released us from the delusions of idolatry and brought us to the knowledge of You, true God and Father. He procured us for Himself as a chosen people, a royal priesthood and a holy nation. Having purified us with water, He sanctified us with the Holy Spirit. He gave Himself as a ransom to death by which we were held captive, having been sold into slavery by sin. He descended into the realm of death through the Cross, that He might fill all things with Himself. He loosed the sorrow of death and rose again from the dead on the third day, for it was not possible that the Author of Life should be conquered by corruption. In this way He made a way to the resurrection of the dead for all flesh. Thus, He became the first-fruits of those who have fallen asleep, the first-born of the dead, that He might be first in all ways among all things. Ascending into heaven, He sat at the right hand of your Majesty on High, and He shall come again to reward each person according to his deeds. ”

As for the blood, it is a means of purification and the bearer of life. That passage in Hebrews is all about the purification of the earthly tabernacle in a symbolic way that reflects Christ’s purification of the Heavenly Tabernacle by His blood. This purification allows us to partake in the Heavenly Tabernacle because we take His life into our own when we partake of His Blood and His Body. Consuming the blood was to consume the life from an animal – and it was forbidden. Yet we are told we must eat Christ’s body and drink His blood to be a part of Him. So in this sense, Christ’s blood is necessary for a restoration, but not in the same way it is often seen in the West. It’s not God seeing us through His blood or demanding a blood payment, but rather God calling use to be purified through the Blood of Christ and conformed to Him. There is some substitutionary atonement going on here too, just not in the same way as thought of in the West. Despite Scripture, the West so often confuses the roles and places the Father as the Judge and Christ as the Advocate who stands in for the sinner, yet it is Jesus who is both Judge AND Advocate. So it is the second person of the Trinity that must be satisfied.

Anyways, I think I’m rambling a bit – and I can’t claim to understand it all as I am always learning more, finding that I actually KNOW less and less as I learn more and more. I do know from experience that many Western ideas are stumbling blocks, especially in our outlook of how we think and what we consider salvation to be. What is most strange to me is that I know I never could have made this journey a decade ago. I see how God has laid a path before me and I have stumbled along it, but managed to stay on it (mostly), though I seem to be hanging on the fringe most of the time.

I want to respond to the main gist of your sense that “there is no debt towards God, but towards debt.” First of all, I see no reason why God needs to pay a debt to death. Why can’t he just do as he did in creation and bring life from the dead (i.e. something from nothing)? But more specifically in the Lord’s prayer Matthew 6:12 it says “forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” καὶ ἄφες ἡμῖν τὰ ὀφειλήματα ἡμῶν ὡς καὶ ἡμεῖς ἀφήκαμεν τοῖς ὀφειλέταις ἡμῶν. So it seems to me that if the debt that we forgive in others is one that they owe us, that the debt that we owe (being analogous) is owed to God. There is something personal going on. God’s wrath and his forgiveness are personal, not just responses to the way the universe works (by the way, using Classical Greek to define contemporary Koine words apart from context is not good lexicography or linguistics). Of course by saying so, it doesn’t mean that his death is a payment for the debt; that would be an unnecessary (though possibly correct) understanding of what God did in Christ. But the shedding of blood in sacrifice is in Hebrews tied directly to the forgiveness of sin. And Christ’s death is explicitly connected to this fact. The thing about blood, though, is that it relates to death. Why did the animals have to die for the atonement of the Israelites (though, of course they didn’t actually cleanse from sins, only Christ’s blood does)? You say that it applies to the earthly vessels, but the author of Hebrews says that that is an example of the true tabernacle in which there was only one once-and-for-all sacrifice (cf. Heb. 9:26)

Robert, you said that you are not sure that it is Orthodox to say that “god needs no payment,” and you asked where I got that. But I was only quoting Jeff.

Jeff, in terms of “logic” it makes much more sense for God to be the one we are in debt to, rather than that God had to pay the devil (as though the devil had a hold over God). How is God having to pay death any different? Anyways, even if I buy into your reasoning, I still don’t think that you’ve explained why there is not forgiveness of sin without the shedding of blood. Perhaps we can’t answer that question, and that is fine by me.

Prometheus, first thank you for your response.

I’d first like to say that the Classical use of a word in Greek is very important because it is formative of the koine. A criticism I have for most all seminarians is that it is koine (more specifically, the version of koine handed down by many Biblical scholars who persistently have mistranslated it) and is not firmly grounded in the literature that influenced the language. In Hebrews especially, the author is clearly grounded in Classical Greek. We should assume that works by Homer, Thucydides, Aristotle, etc are formative and that indicates that meanings from the Classics have an impact. In this case, ἄφεσις and its derivatives pertain directly to bondage. I prefer not to call it debt because our own language confuses the meaning. This “forgiveness” is more about a release from bondage than a pardon from a crime or other infraction. The word is used primarily in Classical works in relation to bondservants. If we are already in bondage to God, why we He need to release us from the bondage He Himself holds us to? We are in bondage to a state (sin and death) that is a result of rebellion.

Forgiveness (as in pardon from a crime or pardon from a debt owed NOT related to a bondservant) is συγγνώμη – and is often rendered as “concession” in English in regards to Scripture.

As for the “payment” language – I speak in regards to the Anselmian concept that essentially has God being the one that holds us in bondage that must be paid by blood. Essentially, the idea that there must be a blood debt paid. The problem with this concept is that it is not generally transformative and the transaction that many Catholics and Protestants see is one where Jesus paid the debt I owed to God. Yet God does not desire sacrifice, as the Scriptures tell us.

God also isn’t paying death, but conquering it. Christ destroys it from the inside by entering into it – at least in its present form. There is an eternal death that the Orthodox view as God’ presence for those who refuse God’s Love and are adamant in their rejection. Yet the state of death as we see it now IS destroyed. It held us in bondage but was transformed when Jesus entered into it and could not be contained by it. This destruction opens the door for resurrection and TRUE conformity to Christ because the stain of the Fall is fully wiped away.

I also must say that I don’t understand all of it nor do I expect to. I am no theologian. My main concern is trying to express that Christ’s sacrifice is much more than just a blood payment. We are told we are in bondage to sin, so there is a necessary payment of some kind – but the payment isn’t one where someone is satisfied – it is one where that which holds us in bondage is utterly destroyed.

Thanks Jeff,

Well said. And the more I think about it, the more the fact of

the Incarnation and the implication that follow it are far fuller

to me. We could go on and on (all Creation’s Redemption be-

ginning with it, it’s implication for Icons…) and much more I’m

sure. God have mercy on us all.

david

When I was Reformed, I remember thinking about the Incarnation in a very heretically monothelite way: my belief in total depravity and inherited guilt made me assume that Christ didn’t assume our totally depraved so called “sin nature”. I now see that such a belief in total depravity seriously undermines the Incarnation – and indeed the entire Gospel – since Christ couldn’t have assumed our human nature in every respect! St Gregory the Theologian said “what is not assumed in the Incarnation is not saved”. This fact alone is enough to demonstrate that the implications of Calvinism/Reformed theology are heretical.

It’s sad now when I hear Calvinists claiming that they best understand “chalcedonian theology” in discussions about icons, etc. In reality, one can’t be a Calvinist/Reformed and believe that Christ is hypostatically 100% homoousious with mankind (and 100% homoousious with God the Father) since then Christ would have had to be guilty of original sin and have a depraved will unable to chose or please God! Calvinist responses to try and escape this conundrum always end up descending into theological absurdities!

I’m not qualified to articulate what are and are not differences in Orthodox vs. Calvinist anthropology, but I’m learning Orthodox do not teach (or should not teach) Christ’s human nature was “fallen” (although we affirm the Virgin shared fallen human nature with all descendants of the first Adam and that Christ did indeed assume His human nature from her). More here: http://www.orthodoxwitness.org/jesus-fallen.php

Orthodox affirm Christ voluntarily assumed what are termed the “blameless” passions (the ability to become hungry, thirsty, tired, etc.). He also voluntarily yielded to death, but as One who is, by nature and definition, God united to humanity in the Person of God the Son, His humanity was not “naturally” subject to the passions or death, as ours is. The testimony of the Gospels is that Christ was without sin and that no-one takes His life, He gives it “willingly.” Christ expresses hunger and thirst and the need for sleep, expresses sorrow, anger, compassion and joy, but there is no record that He ever fell ill–rather healing power went out from Him.

Orthodox agree with Calvin that Christ’s human nature was pure like that of the first Adam before the fall. Orthodox understand this to be the case because in the very act of uniting our humanity to His Deity at conception, it was healed/fulfilled. I’m not sure how Calvin accounts for the distinction in how we view Mary’s humanity vs. that of Christ, but it certainly seems to suggest that even in our fallen sinful state, all the underlying goodness and potential of God’s original creation remains, though it cannot be actualized apart from union with God. Orthodox understand Mary to have been purified from sin (deified) through the grace of the Holy Spirit to the point where she was capable of giving her “yes” to God at the Annunciation. From that point on, having contained Deity in its fullness in her womb, she was no longer capable of sin.

This is a bit tangential, but since the Orthodox lectionary for today includes the Genesis account of Enoch, who “walked with God” and was no more because “God took him”, I’ll point out we have examples of two OT Saints, who, even before the Incarnation, walked so closely with God that they did not undergo physical death, but were transfigured (deified) before death and assumed to heaven–Enoch and Elijah. Not sure how Calvin’s theology of “total depravity” accounts for that.

Total depravity has a whole host of problems that I never saw in the past. As James cited from St. Gregory the Theologian, “what is not assumed in the Incarnation is not saved.”. This refutes the concept of total depravity since Christ was not depraved and thus man could not be saved if he were. So if man is totally depraved, there is no point to the Incarnation at all. If man is not, it means that his image, made according to the Ikon of Christ, is still good but distorted and perverted due to the impact of death, our willful disobedience and separation from the Source Of Life.

Calvin’s view is not necessarily in line with many who used his name to create the Calvinist foundation for theology. Yet the concept of total depravity is not foreign to Calvin. I think a large part of Calvin’s errors come from his insistence on God’s sovereignty – and God is most definitely sovereign, BUT his sovereignty can work with the free wills that have been given in His sovereignty. Man’s choices exist through God sovereignly ordaining their existence. Calvin and his followers would draw a box around the sovereignty issues, just as so many would draw a box around faith to insist that even belief itself was a work, essentially concluding that we have no say in our salvation – God has chosen who is to be damned and who is to be saved. That is at conflict with the scriptures, that so often balance our choices with God’s sovereignty – they both exist and we are called to be God’s coworkers, His synergia.

Total depravity is a stumbling block for many of us coming from the Reformed tradition in that when we hear that Christ took on fully all of humanity, we would have included man’s depraved nature and that would have been wrong. Yet man is not fully depraved and so Christ assumed all of our nature in the Incarnation, but He did so without sin. He took humanity and, truly, all of Creation into Himself and perfected it then He conquered the consequence of our disobedience and arrogance, death itself.

Amen!

Thanks Karen,

I’m not the one to sift all this out just rightly but it is my understanding

that the Orthodox do NOT understand fallen human nature of necessity

as Sinful…unlike Calvin and his doctrine of TOTAL depravity. There is the

possibility of a fallen human sinner yielding himself totally to the Holy

Spirit, resisting all occasion or temptation[s] to sin — as we are told Christ’s

active obedience did. Otherwise Christ’s nature was NOT like mine…and

was His resistance to temptation pretend-like acting…NOT real temptation

“in all points as we” to sin, which He resisted by the power of the Spirit.

Calvin’s Total Depravity demands a totally corrupted human Nature able

ONLY to sin…that must super-regenerated instantaneous upon conception

with no occasion to sin like me. It is a different post-Fall anthropology that

denies what Orthodox theologians would call true/free Humanity. Of course,

this could all be better said than I have. But it IS a different view of both

Fallen human Nature…and Incarnation. Are we saying the same thing

differently? 🙂

much love,

david

It seems to me that you both are on the same page, but concepts and how we describe them have often caused issue in the past (witness the fallout from Chalcedon). I think the logical conclusion of theology involving total depravity would be that Christ was not truly tempted. How could He be under that construct? Even temptation is a sign of depravity according to that doctrine, so the temptation is often described as a temptation that is not akin to our own human temptation. Yet the Scriptures make no indication that there is any difference, nor do the Fathers.

In the total depravity construct, we have no choice in sin. Of course, in that construct it is sin that is the general problem for humanity, not death. In quite a bit of what I’ve heard and read in Orthodoxy, it is often said that death is the central problem for man – cutting ourselves off from God’s sustenance by refusing to be the Priest of Creation and bring all to Him for renewal – and that sin is caused by death itself. Here Orthodoxy embraces a broad cosmology with man at the center – the whole world, indeed the whole kosmos, groans because the center of Creation, mankind, the ones made according to God’s Ikon and made to unify all of Creation (spiritual and physical) through their priesthood decided to strive to be gods of their own making. Death and sin are intertwined, but a choice always remains.

Man could never choose Christ if he were totally depraved, though the Reformed school has often gone around this by stating that the Holy Spirit would go ahead and cause regeneration before a choose was made. Monergism is always prevalent in most Reformed Theology, but a Monergistic stance (and this is usually required for Total Depravity) also denies the full Incarnation, which is synergistic in nature as it is. Even from the declaration, it is synergistic. Mary has a choice to accept or reject what is declared to her. She accepts, becomes the very Temple of God, and all of humanity is blessed through Mary’s obedience. Mankind cannot be totally depraved if Mary can make that choice, though even many Catholics by into it through the “Immaculate Conception” dogma. Yet Mary could be without sin without any such dogma because she was not totally depraved – nor are any of us. We choose to struggle against sin and death WITH God by participating in His Grace or we choose to be enslaved by sin and death, rejecting our call to be coworkers with the Lord of All Creation.

Yes, it seems to me that if “total depravity” means that fallen man has no choice but to sin (i.e., that there is no “common grace” available through the Holy Spirit even to fallen mankind), that would not be an Orthodox faith. Enoch, Elijah and the Theotokos are all biblical examples of theosis by the grace of the Holy Spirit.

From what I am reading in the book I linked above, though, it would be incorrect to say that in His humanity, Jesus overcame temptation as we must only by the grace of the Holy Spirit. That would be to separate the Human Person, Jesus Christ, from the Divine Person, God the Son, which is Nestorian, not Orthodox. Rather, Jesus Christ is One Person (“hypostasis”)–God, the Son–with two natures (human and divine). Therefore, the Man, Jesus, being God by nature (not grace), is already also One by nature with both the Father and the Holy Spirit. In assuming our humanity, His divinity perfected it. His subjection to temptation (testing), His vulnerability to the conditions of the fallen world (i.e., His suffering) was real, but voluntary (not strictly necessary to his perfected human nature nor in part the natural consequence of having an inclination to sin, as it is for us). In voluntary solidarity with us, He shared all the consequences and condition of our sin, except for our sinful inclinations/passions (which I speculate are perhaps what predispose us to the diseases which Christ apparently did not suffer).

Amen to all that!

David,

the Orthodox understanding of “nature” is more like “those qualities which make a human being human.” This is one place where the difference between “nature” and “person” is important. Like the Triune God, of whom we only know what “godness” or the “nature” of God is as we encounter the Person of the Son, we only know what human nature is as we encounter it in unique persons/human beings. So in that sense, it’s not quite on the mark to say that our nature is “fallen.” However, because we live in slavery to the fear of death (Heb 2.14-15) as (the largest?) part of our inheritance from our first parents, in a world that is subject to vanity/uselessness in the slavery of corruption (Rom 8.20-21), each person’s understanding is darkened, like a dirty mirror. Through the sacramental life of the Church and as we engage in askesis, all with a heart open to God, our union with Christ effects a cleansing, bit by bit, of that mirror. We move, bit by bit, toward full humanity, reflecting the likeness of Christ in Whose Image we were made.

Our “unredeemed state” is one in which we act *inhumanely,* not as the fully human beings we were created to be. In this sense, we have fallen a long way. The liturgical hymns of Lent, especially at the beginning, express this very profoundly, but there is no sense that “human nature” is damaged beyond redemption, or depraved to the point of not being human at all.

Hope that helps.

Dana

With regard to the “why blood sacrifice?” thread, I second the recommendation to take a look at the recent “Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy” posts.

Also, I believe this quote from St. Gregory the Theologian is quite relevant:

https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/glory2godforallthings/2008/01/22/st-gregory-the-theologian-on-our-ransom-by-god/

Jeff, thank you, too, for your further explanation.

Firstly, with regards to “God pays death” or such, the reason I used this language is because you did originally (at least twice). Now I see that you are only going with the Christus Victor model, which I think is more consistent.

And re: Classical Greek. First of all, it is doubtful that your claim about ἄφεσις is at all true. ἄφεσις has a very broad meaning. So even if I do grand that Classical Greek informs the style of the author of the book of Hebrews (the author’s Greek is very good), the range of meaning for ἄφεσις cannot be limited to your definition in Hebrews of ἄφεσις as the kind of freedom from bondage that you are speaking of (if I understand you rightly). In addition, particularly since Hebrews was written to Jews and not to those expected to be familiar in the classics, it makes more sense that the LXX usage of ἄφεσις and the typical Hellenistic usage would take precedence. We do need to look at literary context, but Greek literature did not stop in the Classical age with Plato. It continued and the language changed. How the language is used at the time period (synchronic linguistics) is more important than how it was used in a previous period (historical linguistics) unless it can be shown that Classical literature is, in fact, being referenced (for which I would be grateful if you have any studies you can point me towards).

Your use of Greek is misleading also in regards to the word συγγνώμη, which you say is often rendered as concession. What you say is technically true, but the word though rendered this way often in various translations only occurs once in the NT as far as I can tell (1 Corinthians 7:6; and once in Sirach). It is never used in a context where it refers to forgiveness of sins – concession seems to be the correct meaning. Even in Classical Greek concession is a standard meaning for συγγνώμη.

That said, the typical word for forgive in the NT literature is ἀφίημι and forgiveness ἄφεσις “to send away, dismiss, release”. The object that is being forgiven/dismissed is the sin not the person! The person is the indirect object. So God forgives the sin “to/for us.” He does not “free us from our sins” using this word (though Paul says he justifies us from our sin once using δικαιόω). Paul and at least Acts, if not Luke, tends to use the word χαρίζομαι for the word forgive. ἄφεσις as release from debt is a common place in even Classical Greek as is demonstrated by Demosthenes Against Timocrates 24.45: μηδὲ περὶ τῶν ὀφειλόντων τοῖς θεοῖς ἢ τῷ δημοσίῳ τῷ Ἀθηναίων περὶ ἀφέσεως τοῦ ὀφλήματος ἢ τάξεως, ἐὰν μὴ ψηφισαμένων Ἀθηναίων τὴν ἄδειαν πρῶτον μὴ ἔλαττον ἑξακισχιλίων “nor in respect of persons indebted to the Gods or to the treasury of the Athenians, for remission or composition of their debt, unless permission be granted by not less than six thousand citizens” -translation found at Perseus-(I don’t think that “bondservant” is at all in view here or in the Lord’s prayer.)

Your explanation of ἄφεσις does not explain how God forgives (i.e. sends away) our debts as we forgive (i.e. send away) the debts of our debtors without God or us being the one(s) owed. The Lord’s Prayer is the backdrop to which I understand “forgiveness of sins.” You prefer not to use the word debt, but I’m not translating the word ἄφεσις or its derivatives by debt. I’m translating the word ὀφέλημα as debt . . . which it is! “send way our debts as we send away [those] of our debtors.” There is no doubt in this context. See also the parable Jesus uses as well in Matthew 18:21-35 which is a perfect explanation of the Lord’s Prayer. I argued above that just as others owe a debt to us when they sin against us (so to speak), so we must owe a debt to God in an analogous way for Christ’s metaphor(?) to make sense. As the Psalmist says, “against you and you alone have I sinned.” It is God, not death, to whom we owe a debt.

Back to the shedding of blood. If God can “just forgive” us (as some claim), why did he have to die? Why could he not just have destroyed death by fiat? I’m not saying I have an answer or that there is one that is revealed. But it is a question related to why “there becomes not sending away [of sins] without the shedding of blood.” So again, why can God not “send away” our sins without the shedding of blood? I don’t know, but I will look at the article Karen posted.

You mention, too, substitutionary atonement. Could I suggest that Christ tastes death for us (whyever that is necessary) and in baptism/faith we taste death with him so that we also will join him in resurrection. We deserve to die (however you want to take that), and he died in our stead, but in such a way that when we are incorporated into him, we also die and rise again in spirit and one day will also die and rise again in body.

(Robert you can edit this out if you think it is too strong – and no offense intended, Jeff) BTW, though you may be as much of an expert in Greek as I am – I teach it for a living, both Classical and Koine – I am unlikely to concede the points about the Greek unless you offer evidence from Greek texts (Biblical or Koine), Hebrews, and/or articles on the concept of ἄφεσις. I have never had the experience of studying in seminary (where do your priests go to study theology?). My BA is in Ancient Languages and my MA in Classics (both Greek and Latin) with fifteen years of Greek experience. I have often felt the same way about seminarians. Yet they are not wrong by virtue of being seminarians; they are often wrong because they think they know a lot when they have very little experience with Greek. And I am not a seminarian or wrong by virtue of disagreeing with your understanding of the Greek language. If your training and/or experience is any less than that of an expert and you are making these claims about seminarians (or Biblical scholars who dedicate their lives to working with the Greek language) mistranslating the Greek text I suggest you read a lot of non-Biblical Greek as well as Biblical Greek from both Classical and Koine periods as well as taking a basic linguistics course on diachronic and synchronic linguistics before saying too much about other peoples’ Greek abilities. If you can offer me good evidence that the book of Hebrews would be using non-typical style/meaning for the Hellenistic period as well as that the Greek in Hebrews (and elsewhere in the NT) shows signs of such a specific (atypical) meaning for ἄφεσις as you give it andthat there is good reason for the author of Hebrews to know that his Hebrew audience was to know the Classicizing style he was making use of well enough to distinguish his special meanings from that of typical Koine, I am happy to hear it.

Regarding your question on forgiveness you might want to read (if you have not already) On the Incarnation, by St. Athanasius. He goes to great lengths to discuss death and forgiveness, though it has been so long I do not recall where it is in the book. It’s a short read anyways, so it shouldn’t take very long to read the entire thing.

John

No offense taken. I enjoy the discussion. I also cannot claim to be as strong with the Greek as you. I took Classical Greek in college and have kept up with it, but I would not consider myself a scholar and I live in a community surrounded by it (my town is right next to Tarpon Springs, FL). So I certainly will yield on your expertise there and I thank you for the detail you’ve provided on the word usage – it has been enlightening to me.

Karen did provide a good reference to Gregory the Theologian and John also has a great recommendation if you have yet to read Athanasius’ On The Incarnation. Quite a bit of my own change in perspective on this comes from reading the Fathers. I’d also recommend Schmemann’s For The Life Of The World as that deals with the Blood of Christ specifically as Eucharist.

Was Hebrews written to Jewish Christians? We assume it and it seems likely, but it is not a certainty. Certainly the assumption named the book. Yet there has long been a question if it was written by a Jew (I think most don’t believe St. Paul wrote it, though Orthodox tradition sticks with that). All that aside, I do tend to think it IS written to a Jewish audience, though I’d suspect that early Christians heard the Greek OT whenever they gathered together since that was the Scripture (and likely included the Deuterocanonical works).

I think ultimately that forgiveness, restoration, and regeneration are all tied together in the blood, but not in the punitive sense. The Western way of thinking is generally that Christ’s blood is substitution for our own. The Eastern mode of thought tends to be that it is through Christ’s blood that we take on His life in us. Blood was used in the sacrifices that foreshadowed Christ’s, but it was never consumed because the life is in the blood (Gen. 9:4-5).

The most dramatic presentation of this is the Passover. The Hebrews are protected by the blood and saved by it. Yet it is more about identifying with the blood than the blood serving as a substitution for them. The Resurrection from the earliest times has been called our Pascha, our Passover.

Timothy Copple puts it much better than I:

“As you can see, forgiveness is more than simply God pardoning us. It involves that, but is also includes the fixing of the problem, cleansing of the sin and its effects upon us. That effect is bondage to death. Forgiveness, then, includes our release from bondage.

Even in the juridical view, this understanding is inherent. The judge releases one from prison because God declares them “not guilty.” Otherwise, there is no real forgiveness. By God’s forgiveness becoming a reality in our lives, God doesn’t just pardon us, but frees us from our bondage. In Orthodoxy, that bondage is to death that holds us captive. Forgiveness includes the concept of giving us life.

It is this fuller understanding of forgiveness of which the Scriptures speak in proclaiming that without the shedding of blood, there is no remission of sins. Even the word used in Hebrews instead of forgiveness contains a medical meaning: the remission of a sickness. Our sins to be remitted and forgiven must also have their consequences and effects upon us remedied. Without that, such pardon is meaningless. As meaningless as if the judge said to someone he just declared “not guilty,” “Take him back to his prison cell.” What good does such forgiveness do if one remains in bondage?

This is where the blood comes into play in regards forgiveness. The truth in the Bible is that God is always ready to forgive us. The only real requirement He has is repentance.”

From Psalm 51: “For You do not desire sacrifice, or else I would give it;

You do not delight in burnt offering. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit,

A broken and a contrite heart—These, O God, You will not despise.”

I guess what I’m trying to get at is the fuller meaning of forgiveness, released from a penal context. Blood WAS required because it was necessary to change our very lives. It is through the blood that we partake in Christ’s life and take Him into us. Sacrifice was required for salvation, but not in the sense of paying for the crime that led to our jail term. As I understand it, death is not a penalty, but a consequence. Man was meant to bring all Creation in offering before God, renewing it from the eternal fount of all power. Instead, man has cut Creation off from that and entropy has taken hold; decay has set in. Man is eternal because that is how he was made, thus death is eternal decay. First the body decays, the soul unnaturally exits, and then the soul continues to decay. It would go to Sheol or Hades where it would have lain eternally if not for its destruction. That destruction opens the door to resurrection, but even then it is possible for the reprobate to reject God and be cut off from Him – but that will be agony when He is revealed in His Glory.

Many issues spring up because how we in the West view salvation is different from how it is viewed in the East – and much of this is because we often don’t view the fullness of the Incarnation, instead often limiting it to a mere substitutionary atonement.

Thank you Jeff.

Your post was clear. I would love, though, if you would address the question of “debt” towards God that we see in the Lord’s Prayer. None of your explanation shows how our offenses are an offense against God or a “debt” towards him and what the shedding of blood has to do with the forgiveness of that debt. (i.e. it seems as if you work very hard to avoid the idea that by sinning we are offending God in a similar way to how we are offended when someone sins against us)

A note about Psalm 51 and about Hebrew poetry. Very typically both in the Old Testament and New, the writer(s) will not say, as we would, “not merely this, but this” they will say, “not this, but this.” For instance: “I desire mercy not sacrifice” is not a phrase that is meant to abrogate the prescribed sacrifices. It means “Sacrifice means nothing to me without mercy.” I’m not saying that this is necessarily what Psalm 51 is doing, but it could be a component. Even if not, it is important that what the Psalmist (David) is saying is regarding an offense for which there was no sacrifice – murder and adultery. Only God can forgive such sins. But the NT (somewhere) says that Jesus brought forgiveness for sins for which there was no provision under the law.

That said, I would not deny the dimension of the work of God in Christ on the cross as also Christ destroying death from the inside out. To be metaphorical, death got more than it bargained for when it swallowed Jesus.

I will do my best to read On the Incarnation soon. I enjoyed Saint Gregory’s quote on the link that Karen gave. I’ll try to follow up on that lead as well.

Much of the problem here lies in my own fashion in communicating and overstating an issues – entirely my own fault. I stated too strongly about the payment issue in an attempt to reject the concept of penal substitutionary atonement.

Again, I’ll rely on Timothy Copple to explain it better than I:

“In the juridical view of the atonement, the problem is that God cannot forgive us until His divine justice is satisfied. In the Orthodox view of the atonement, it is more like the father of the Prodigal Son who placed no demands for repayment or punishment before he would forgive his son. It is like the master who forgave his servant a lifetime of wages owed him, requiring not one cent of repayment other than to go and do likewise. The issue in Orthodoxy is not whether God is able to forgive; He is always ready to forgive. It is whether we are able to accept and incorporate that forgiveness into our lives. To do that, we have to have His life in us. God needs to free us from the bondage of death. Otherwise, God’s forgiveness is pointless and does us no good.

For us to obtain a full and complete forgiveness, it requires the shedding of blood. For by the shedding of blood are we able to partake of His life, be released from the bondage of sin and death, and God’s forgiveness of our sins becomes a complete reality in our lives. Until we have that life in us, God’s forgiveness is only an unrealized potential. Accepting His forgiveness freely offered is to unite to Him and live in Him. We do that through the partaking of the blood of Christ and having death pass over us.”

I would also agree that there is a debt to God that is caused by our sin (and also a positive debt since it is God that has willed our existence and sustained us via His grace (grace here seen as God’s uncreated energies that we are called to participate in). The Lord’s Prayer relates to how Copple describes it – can we accept God’s forgiveness? If we show no mercy to our brethren, how can we experience and accept Christ’s? I’d also argue for this occurring in community since this is depicted in the plural (forgive us OUR debts) that implies a covenant community behind it.

The blood allows us to join Christ, conform to Him, and be able to truly accept the forgiveness freely offered. Yet it is all quite a bit of covenantal language, but we do enter into a New Covenant.

Mankind is transformed by Christ’s blood because we are able to take on His character through it. He is the True Adam, the One whose Image we were made according to, but we must be joined to Him for that to occur and in that we do have our own will to reconcile.

There is an aspect of penalty that comes from God as well, so the juridical view is not entirely wrong. There is a payment of release of sorts, but I think it’s much more complex than the simple transaction it is often made out to be: “God is angry with me and demands my life for what I have done. Jesus offers His life instead of mine, so I am free. All I have to do is accept this.” It is far more complex than that and requires us to be God’s coworkers. The juridical view ignores the renewal of humanity through Christ and the therapy prescribed in Holy Tradition to help us become like Christ more and more.

We are forgiven of sin through Christ, but it is not merely because He was a substitution (and that aspect does also exist), but much more. Forgiveness is a two way street. While we have nothing to forgive God for, we must be able to accept His forgiveness offered to all through Christ and be forgiving to all others, even to the point of loving our enemies. And we are not truly capable of love until we take on Christ.

I think our “debt” of obedience to God was fulfilled by Christ on the Cross. Christ’s atonement turns away God’s wrath because those who are in Christ are cleansed and empowered by Christ’s life in them to turn from their sin, thus removing the cause of wrath. Remission of sin and actual freedom from sin are connected in Orthodox understanding.

Thank you Jeff and Karen.

I’m glad that you give some space to the judicial aspect since so often I feel that it is easy for the Orthodox to disregard the clearly judicial and payment aspects of the New Testament. That would be a difficult pill for me to swallow. I think it is interesting that when Paul speaks of slavery to sin and slavery to God he adds “I am speaking in human terms.” That is, our metaphors and similes are only so helpful. Father Andrew Damick has said that there is a lot more variety in Orthodox thinking than many give it credit for. Many of the things commonly said are not dogma or doctrine but theology (i.e. elaborations of dogma that are meant to help us understand what it is that we are talking about). Damick Link

Here is what one Orthodox theologian has said:

“Thou hast taken upon Thyself the common debt of all in order to pay it back to Thy Father – pay back also, O guiltless Lord, those sins with which our freedom has indebted us. Thou hast redeemed us from the curse of the law by Thy precious blood. Deliver also those redeemed by Thy blood from harsh justice!” (St. Ephrem the Syrian, *A Spiritual Psalter* #102)

Karen, what many Protestants seem to see as imputed righteousness is a serious problem. For vary many Protestants (especially the Reformed) the focus is on how we are simul iustus, simul peccator at the same time just at the same time sinner. We are incapable of holiness as Christians. We are seen as holy because we are seen through the lense of Christ’s holiness. I think the New Testament promises far more than that (cf. Romans 6-8).

The Catholic view (or at least the caricature of it) of imparted righteousness seems to have its own problems (though the impartation does not make us autonomous, since all righteousness comes from God so that grace is constantly necessary).

The Orthodox view when clearly stated has the advantages of the Catholic view, but without grace becoming a created thing.

The point being life in Christ.

There is certainly a juridical metaphor in there. I think the trouble comes in when: 1) a modern juridical conceptual framework is imposed on the biblical one (i.e., law as a somewhat arbitrary legal code imposed to maintain social order vs. the OT law which is a true, but incomplete, expression of God’s will and character, of which Christ is the full expression), and 2) it is made the central defining mechanism, not just one of several metaphors, for understanding the nature of the atonement.

Karen, I have the same book “fallen Jesus?” And I was told by someone I trust to simply stick to saint Maximus the Confessor for the author confused a number of concepts. And so double check what the book says with saint Maximus.

Thanks for that tip, jnorm. I’m finding the author seems to repeat himself a lot. I find myself thinking as I’m reading, Isn’t that what he just said in the last section/chapter?! 🙂