Did John Calvin believe in the “Fall of the Church”? That is, did he believe that the early Church apostatized from Apostolic doctrine and worship, and that true Christianity was not restored until the Protestant Reformation? The “Fall of the Church” is widely held among Protestants but some of our readers deny that Calvin held this view calling it a “canard.”

Did John Calvin believe in the “Fall of the Church”? That is, did he believe that the early Church apostatized from Apostolic doctrine and worship, and that true Christianity was not restored until the Protestant Reformation? The “Fall of the Church” is widely held among Protestants but some of our readers deny that Calvin held this view calling it a “canard.”

Part I. The BOBO Theory

Fuller Seminary professor and missiologist Ralph D. Winter noticed that many Evangelicals are under the impression that Christianity “Blinked-Out” after the Apostles and then “Blinked-On” with the Protestant Reformers.

. . . “BOBO” theory—that the Christian faith somehow “Blinked Out” after the Apostles and “Blinked On” again in our time, or whenever our modern “prophets” arose, be they Luther, Calvin, Wesley, Joseph Smith, Ellen White or John Wimber. The result of this kind of BOBO approach is that you have “early” saints and “latter-day” saints, but no saints in the middle.

Winter noted that this view has resulted in Protestants having little interest in the one thousand years of church history before the Reformation because nothing spiritually important was happening between the New Testament church and the 1500s. Winter wrote about the negative effect this had on Protestants:

But this only really means that these children do not get exposed to all the incredible things God did with that Bible between the times of the Apostles and the Reformers, a period which is staggering proof of the unique power of the Bible! To many people, it is as if there were “no saints in the middle.”

The BOBO theory is crucial to Protestantism’s self understanding. Protestants believe that after the calamitous “Fall of the Church,” the Reformation marked a return to the early Church – the way it was meant to be. Without this justification, the Reformation would be a schismatic deviation. Sometimes one is presented with a more subtly nuanced version that allows for a small continuing “Remnant Church” present throughout church history that held on to the True Faith – of course assumed to be more or less Protestant. The problem with this view, aside from the lack of historical evidence, is that this supposed historic “Remnant” existed independently of any historically recognized Church be it Orthodox or even Roman Catholic.

Did Calvin Hold to the BOBO Theory?

In “Necessity of Reforming the Church” Calvin made reference to the “primitive and purer Church” (p. 215). In his Institutes Calvin saw icons, altars, vestments, ritual gestures, and other decorations as signs of the early Church’s decline and degeneration.

First, then, if we attach any weight to the authority of the ancient Church, let us remember, that for five hundred years, during which religion was in a more prosperous condition, and a purer doctrine flourished, Christian churches were completely free from visible representations. Hence their first admission as an ornament to churches took place after the purity of the ministry had somewhat degenerated. I will not dispute as to the rationality of the grounds on which the first introduction of them proceeded, but if you compare the two periods, you will find that the latter had greatly declined from the purity of the times when images were unknown. (Institutes 1.11.13, p. 113; emphasis added)

Calvin also traced the fall of the church to the emergence of liturgical worship, something that commenced soon after the original Apostles passed on. Calvin wrote in the Institutes:

Under the apostles the Lord’s Supper was administered with great simplicity. Their immediate successors added something to enhance the dignity of the mystery which was not to be condemned. But afterward they were replaced by those foolish imitators, who, by patching pieces from time to time, contrived for us these priestly vestments that we see in the Mass, these altar ornaments, these gesticulations, and the whole apparatus of useless things. (Institutes 4.10.19, p. 1198; emphasis added)

In this passage we find a succession of: (1) “the Apostles,” (2) their second generation “immediate successors,” and (3) the subsequent generations of “foolish imitators.” What Calvin is asserting here is that the Eucharist underwent considerable change shortly after the passing of the Apostles resulting in the “Fall of the Church.” That all this happened within a few decades or in the first century after the Apostles’ repose raises serious questions about Calvin’s understanding of post-Apostolic Christianity. Calvin here is implying that the Apostles’ disciples disregarded Paul’s exhortations to “preserve” and “guard” the Faith “with the help of the Holy Spirit” (see 2 Timothy 1:14). This alleged “Fall” raises serious questions about the sincerity of the Apostles’ disciples and about the Holy Spirit’s presence in the early Church. This is not a small claim but very serious accusations!

We have here two different versions of the “Fall of the Church”: (1) an immediate Fall right after the passing of the original Apostles (Institutes 4.10.19) and (2) a later Fall after the first five centuries (Institutes 1.11.13). This inconsistency makes it hard for a church history major like me to ascertain when the “Fall” took place, who instigated the “Fall,” and what was the driving force behind the “Fall.”

The Blinked-Out, Blinked-On trope is especially evident in Calvin’s essay “The Necessity of Reforming the Church”:

This much certainly must be clear alike to just and unjust, that the Reformers have done no small service to the Church in stirring up the world as from the deep darkness of ignorance to read the Scriptures, in labouring diligently to make them better understood, and in happily throwing light on certain points of doctrine of the highest practical importance. (“Necessity” pp. 186-187, cf. p. 191; emphasis added)

We maintain to start with that, when God raised up Luther and others, who held forth a torch to light us into the way of salvation, and on whose ministry our churches are founded and built, those heads of doctrine in which the truth of our religion, those in which the pure and legitimate worship of God, and those in which the salvation of men are comprehended, were in a great measure obsolete. (“Necessity” pp. 185-186; emphasis added)

Therefore, from the evidences above it is clear that Calvin did in fact hold to the BOBO theory of church history. Orthodox theologians and historians can in many ways agree with Calvin about the Roman Church’s decline. However, where many Orthodox view Rome’s decline as having occurred after the Great Schism of 1054, Calvin viewed the “Fall of the Church” as having occurred during the time of the Ecumenical Councils when Rome was in communion with the other patriarchates. This is something Orthodox Christians would find problematic. Orthodoxy believes that it has faithfully kept and preserved Apostolic Tradition for the past two thousand years and because it never suffered a “Fall” is the same Church as the early Church.

Calvin’s Dispensationalism

Calvin’s understanding of church history as discontinuous marked by ruptures is not all that anomalous. One sees a similar understanding in Calvin’s view of the relationship between the Old and New Covenants. He wrote:

For if we are not to throw everything into confusion, we must always bear in mind the distinction between the old and new dispensations, and the fact that ceremonies, whose observance was useful under the law, are now not only superfluous but absurd and wicked. When Christ was absent and not yet manifested, ceremonies by shadowing him forth nourished the hope of his advent in the breasts of believers; but now they only obscure his present and conspicuous glory. We see what God himself has done. For those ceremonies which he had commanded for a time he has now abrogated forever. (“Necessity” p. 192; emphasis added)

The problem with this statement is that it is unbiblical. It contradicts Matthew 5:17 where Christ taught that he did not come to abolish (abrogate) the Law but to fulfill it. With the New Covenant came a new priesthood based on Christ’s priesthood and a new form of worship based on Christ’s sacrificial death on the Cross. Here It seems is the root cause of Calvin’s mistake – he tragically transposed the Protestants’ controversy with Roman Catholicism onto the early Church.

Part II. The Historical Evidence

Calvin’s belief that the early church fell away from the Apostles’ teachings can be tested by examining the earliest Christian writings with respect to: (1) the Eucharist, (2) the use of icons in worship, (3) the Gospel Message, and (4) church government (the episcopacy). We will be using the following writings: (1) the Didache (c. 90-110), (2) the letters of Ignatius of Antioch (d. 98-117), (3) Justin Martyr’s Apology (d. 165), and (4) Irenaeus of Lyons’ Against Heresies (d. 202). These comprise the earliest Christian writings outside the New Testament and thus give us valuable insights into the faith and practices of the post-Apostolic Church and allow us to ascertain the degree of continuity in faith and practice.

The Eucharist

One way of testing Calvin’s “Fall of the Church” theory is by examining early Christian worship. One feature that immediately stands out is the importance of the Eucharist for the early Christians and their sacramental understanding of the Eucharist.

When I was a Protestant one thing I always heard at the monthly Holy Communion service was the pastor emphasizing that the bread and the grape juice were just symbols. So when I read the early church fathers I was struck by the fact that none of the church fathers taught that the bread and the wine were just symbols. As a matter of fact, they taught something quite different. Ignatius of Antioch referred to the Eucharist as the “medicine of immortality (Letter to the Ephesians 20:2). His belief in the real presence can be found in another letter.

I desire the “bread of God,” which is the flesh of Jesus Christ, who was “of the seed of David,” and for drink I desire his blood, which is incorruptible love. (Letter to the Romans 7.3; emphasis added)

Belief in the real presence can also be found in Justin Martyr.

For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh. (The First Apology 66; emphasis added)

Another early witness to the real presence in the Eucharist is Irenaeus.

When, therefore, the mingled cup and the manufactured bread receives the Word of God, and the Eucharist of the blood and the body of Christ is made, from which things the substance of our flesh is increased and supported, how can they affirm that the flesh is incapable of receiving the gift of God, which is life eternal . . . . (Against Heresies 5.2.3; emphasis added)

The Eucharist was central to early Christian worship and theology. In the early church to deny the real presence in the Eucharist was to commit heresy. Ignatius of Antioch wrote regarding the heretics:

They abstain from Eucharist and prayer, because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ who suffered for our sins, which the Father raised by his goodness. (Letter to the Smyrneans 7.1; emphasis added)

As an Evangelical I was struck by the fact that it was the heretics who denied the real presence in the Eucharist. Just as significant is Ignatius’ insistence that the Eucharistic celebration is integrally linked to the office of the bishop. In other words, early church government was episcopal, not congregational!

Be careful therefore to use one Eucharist (for there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup for union with his blood, one altar, as there is one bishop with the presbytery and the deacons my fellow servants), in order that whatever you do you may do it according to God. (Letter to the Philadelphians 4.1)

As an Evangelical in a congregationalist denomination I was unsettled by the fact that modern Evangelicalism was much closer to the early heretics than they realize. This started me thinking: Was it the early Christians who fell away or the modern Evangelicals? Why is Evangelicalism so different from the early Church?

Thus, the evidence shows that the Eucharist was at the center of early Christian worship – not the sermon. By subtly displacing the Eucharist and putting the sermon at the center of Christian worship, Calvin detached the heart and focus of worship from its Eucharistic moorings. Those who came after Calvin would go even further and strip Christian worship of its sacramental character. One only need witness today’s Protestant worship to see the absence of the Eucharist most every Sunday – much less the real presence of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist! This has resulted in the recent move among Protestants to restore liturgical worship, but even then the sermon still overshadows the Eucharist.

Altar, Vestments, and Ceremonies

Calvin taught that the early church celebrated the Eucharist with “great simplicity” (Institutes 4.10.19). But he is arguing from silence. He seems to be assuming that because the New Testament writings had little to say about how the early Christians worshiped that their worship was devoid of liturgical rites and ceremonies.

When we read the Old Testament we find biblical support for the use of altars, vestments, and ceremonies in worship. The Tabernacle had two altars: one for burnt offering (Exodus 27:1-8) and another for incense (Exodus 30:1-10). The priests were dressed in ornate vestments of gold, blue, purple, and scarlet in accordance with God’s directions to Moses (Exodus 28:1-5). Thus, Old Testament worship was an elaborate affair with processions, music, and ceremonies – nothing at all like the stark austere Reformed worship!

When we come to the New Testament we find no evidence of Old Testament worship being abolished and the instituting of minimalist worship with bare walls. We do, however, find hints of Old Testament worship being carried over into Christianity. In Hebrews 13:10 is a cryptic statement: “We have an altar . . . .” This was a reference to the Eucharistic celebration. The Christians saw themselves as the New Israel of Christ and in that light viewed the Eucharist as the continuation and fulfillment of the Old Testament sacrificial system. So we shouldn’t be surprised by Ignatius’ references to a Christian altar.

Be careful therefore to use one Eucharist (for there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup for union with his blood, one altar . . . . (Letter to the Philadelphians 4.1; emphasis added)

And,

Hasten all to come together as to one temple of God as to one altar, to one Jesus Christ, who came forth from the one Father, and is with one, and departed to one. (Letter to the Magnesians 7.2; emphasis added)

If the early Christians understood the Church as the Temple of the New Covenant then it is no surprise that they would view the clergy as the priests of the New Covenant (see Isaiah 66:19-21). All this makes sense in light of the fact that the Eucharist was central to early Christian worship. Thus, the wooden table or box (ark) where the priest celebrated the Eucharist would be considered an altar.

Icons

Calvin believed that the early churches were “completely free from visible representations” (Institutes 1.11.13). His assumption seems to be that because the New Testament had little to say about religious pictures in church buildings that icons were not part of early Christian worship.

But Calvin’s iconoclasm is weakened when we take into account the Old Testament passages about the images of the cherubim in the Tabernacle (Exodus 26:1, 31) and in the Temple (1 Kings 6:29-32).

Thus, the Old Testament places of worship were filled with visual representations: cherubim, palm trees, and flowers. Images of the cherubim were depicted on the curtain for the entrance to the Holy of Holies as well on the walls of the inner and outer rooms of the Temple. See my article: “The Biblical Basis for Icons.” In light of an absence of any New Testament passages mandating the removal of icons or the abolition of Old Testament worship we can assume some continuity between Jewish worship and early Christian worship.

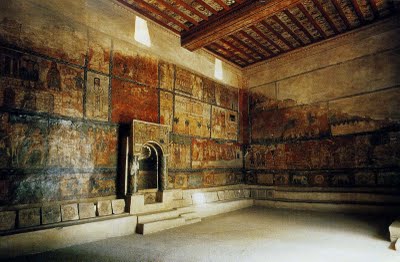

Recent archaeological research found that Jewish synagogues around the time of Christ were not bare rooms devoid of images but embellished with religious decorations. See my article “Early Jewish Attitudes toward Images.” Especially damaging to Calvin’s argument are the recent archaeological findings of images in the Jewish synagogue and Christian church in the town of Dura Europos which was buried circa 250. Taken together the biblical and archaeological evidences present a strong refutation of Calvin’s “Fall of the Church” theory.

Dura Europos Synagogue. Source

Defending the Gospel Message

A study of early church history shows that the church faced numerous theological challenges: Ebionitism which affirmed Jesus as Messiah but not as divine, Docetism and Gnosticism which denied that Jesus was truly human, Marcionism which saw the Old and New Testaments as representing two different religions and deities, and Montanism a prophetic movement which held that Apostolic tradition was superseded by the new prophecies. One thing that is striking is the absence of any controversy during this period over the issues mentioned by Calvin: liturgical worship, vestments, incense, or icons. Surely if the early Church had drifted away from the Apostles’ teachings as Calvin alleged someone would have spoken up?

The Apostle Paul was not unaware that the Church would come under attack by heretics so he took steps to ensure the safeguarding of the Gospel. At Timothy’s ordination to the office of bishop he admonished:

What you heard from me, keep as the pattern of sound teaching, with faith and love in Jesus Christ. Guard the good deposit that was entrusted to you—guard it with the help of the Holy Spirit who lives in us. (2 Timothy 1:13-14; NIV; emphasis added)

The phrases “pattern of sound words” and “good deposit” referred to a set of core doctrines to be held by all Christians. This was the basis for the theological unity of the early Church, to deviate from this doctrinal core was to fall into heresy. The early Christians were diligent in defending the orthodoxy of the Church. Ignatius warned Polycarp against tolerating those who taught “strange doctrine.” (Ignatius to Polycarp 3) A similar warning against “another doctrine” is found in Didache 11.1 and in Polycarp’s Letter to the Philippians (7.2).

In Against Heresies 1.22.1 Irenaeus referred to the “rule of faith (truth)” by which one could determine someone adhered to the Apostolic teachings or not. In Against Heresies 2.9.1 Irenaeus remarked how the entire Christian Church received the Apostles’ Tradition. Polycarp in Letter to the Philippians 7.2 made reference to the traditioning process as well.

The early church preserved the Apostles’ teachings by means of the bishop having received a body of teaching from his predecessor, the bishop as the primary teacher of the local church, and the congregation united with the bishop at the weekly Eucharistic celebration. For Irenaeus theological orthodoxy was linked to the bishop’s role in the traditioning process.

True knowledge is [that which consists in] the doctrine of the apostles, and the ancient constitution of the Church throughout the whole world, and the distinctive manifestation of the body of Christ according to the successions of the bishops, by which they have handed down that Church which exists in every place, and has come even unto us, being guarded and preserved, without any forging of Scriptures, by a very complete system of doctrine, and neither receiving addition nor [suffering] curtailment [in the truths which she believes]; . . . . (Against Heresies 4.33.8; emphasis added; see also 3.3.1)

Irenaeus described his mentor Polycarp’s efforts to remember accurately the teaching and example of his mentor the Apostle John.

And as he [Polycarp] remembered their words, and what he heard from them concerning the Lord, and concerning his miracles and his teaching, having received them from eyewitnesses of the ‘Word of life,’ Polycarp related all things in harmony with the Scriptures. These things being told me by the mercy of God, I listened to them attentively, noting them down, not on paper, but in my heart. And continually through God’s grace, I recall them faithfully. (in Eusebius’ Church History 5.20.7, NPNF p. 371; emphasis added)

In other words, the early Christians did not play fast and loose with the Apostles’ teachings as one might infer from the “Fall of the Church” theory. Rather, they sought to preserve and transmit faithfully the Apostles’ teachings to later generations. If anyone dared to stray from the regula fidei they would have been excluded from the Eucharist. That is why the episcopacy and the Eucharist were so critical to the theological integrity of the early Church.

Priests and Bishops

Just as the Jewish temple had a priesthood so too did the early church have a priesthood (clergy). Under the New Covenant the Eucharist was based on Christ’s once and for all sacrifice on the Cross. The bishop along with the priests (presbyters) presided over the Eucharistic assembly. Ignatius was an early witness to the three orders: bishops, priests, and deacons.

Be zealous to do all things in harmony with God, with the bishop presiding in the place of God and the presbyters in the place of the Council of the Apostles, and the deacons, who are most dear to me, entrusted with the service of Jesus Christ . . . . (Letter to the Magnesians 6.1; emphasis added)

He viewed this threefold hierarchy, not as optional, but as necessary.

Likewise let all respect the deacons as Jesus Christ, even as the bishop is also a type of the Father, and the presbyters as the council of God and the college of Apostles. Without these the name of “Church” is not given. (Letter to the Trallians 3.1; emphasis added)

In his Letter to the Smyrneans 8 Ignatius stressed that the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper were not valid unless done with the consent of the bishop. Irenaeus made a similar point as well:

Wherefore it is incumbent to obey the presbyters who are in the Church, — those who, as I have shown, possess the succession from the apostles; those who, together with the succession of the episcopate, have received the certain gift of truth, according to the good pleasure of the Father. (Against Heresies 4.26.2,)

An examination of church history shows that the episcopacy was the universal form of church governance. It was not until the Protestant Reformation that we see the emergence of novel polities: congregationalism, presbyterianism, and independent non-denominationalism.

Assessing Calvin’s “Fall of the Church” Theory

While insightful, Ralph Winter’s essay seems to have overlooked some of the startling theological implications of the BOBO theory. One implication is that the Holy Spirit was active in the early days of the church then disappeared for the next thousand years or more then reappeared with the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s! Also, Winter did not discuss Christ’s promise in John 14:26: “but the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you all things and will remind you of everything I have said to you.” This has profound implications for the doctrine of God’s sovereignty in history. For Reformed Christians this gap in church history also has troubling implications for God’s ability to keep his covenant promises. How can a Reformed Christian square his belief in the sovereignty of God and covenant theology with the “Fall of the Church” theory proposed by Calvin?

For me as a church history major the “Fall of the Church” theory stems from a foundational flaw. The “Fall of the Church” theory makes sense if one reads church history with the assumption that the early Christians were Calvinists. Any hints of liturgical worship among early Christians, i.e., anything unlike Reformed worship, can be attributed to their “falling away.” But this approach is like taking a meat cleaver and hacking church history into pieces! It utterly disregards the notion of historical continuity and development. A more reasonable approach is to view early Christian worship of the second century described in the post-apostolic writings as flowing from the Christian worship of the first century described in the New Testament. In light of the evidences one can then decide whether or not early Christian worship was liturgical, simple or elaborate, with or without icons. And whether or not there was continuity or significant departures in practice or doctrine. The second century writings are more useful for understanding first century Christian worship than those from the 1500s, the time of rhe Reformers.

Calvin’s BOBO theory of church history was influential in the Reformed tradition until Philip Schaff gave his “Principle of Protestantism” address in 1844. In it Schaff proposed that the Protestant Reformation represented the flowering of medieval Catholicism. Where Calvin saw discontinuity and rupture, Schaff saw continuity and evolution. Thanks to Schaff church history became an academic discipline that stood on its own independent of theology. This allowed for the emergence of historical theology. Jaroslav Pelikan’s The Christian Tradition is probably one of the finest works of historical theology in the twentieth century and extremely useful for understanding commonalities and divergences in the different theological traditions. [Note: This eminent Yale historian and long time Lutheran pastor to the surprise of many converted to Orthodoxy!]

Calvin’s theological system is complex and contains contradictions. These contradictions offer points of contact between the Reformed tradition and Eastern Orthodoxy. Despite his view that early Christianity had deteriorated over time, Calvin at times held some of the early church fathers in high regard. Calvin was not averse to quoting the church fathers against his Roman Catholic opponents. In his “Reply to Sadolet” Calvin affirmed the antiquity principle asserting “our agreement with antiquity is far closer than yours” (p. 231). Calvin’s arguments against the medieval church may be valid but does it likewise apply to the Orthodox Church? It has been noted that the Latin Church under the influence of medieval Scholasticism and the rise of the legal schools drifted away from its patristic roots. This suggests Calvin may have been a victim of historical circumstances. Calvin’s openness to the church fathers and the early Church laid the foundation of Mercersburg Theology in the 1800s and the attempt by Nevin and Schaff to bring back the catholic dimension to the Reformed tradition.

So while Calvin’s BOBO theory of church history is seriously flawed, he is to be commended for his willingness on occasion to draw on the early church fathers. This gives Reformed Christians an advantage over their Evangelical counterparts when it comes to engaging Eastern Orthodoxy. I found in Mercersburg Theology and the Reformed tradition a point of contact leading me to the early church and ultimately into the Orthodox Church. I am deeply indebted to Mercersburg Theology for the intellectual tools that enabled me to critically examine Reformed theology even though it had unintended consequences like my eventually converting to Orthodoxy.

Robert Arakaki

Source

Calvin, John. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Ford Lewis Battles, translator. The Library of Christian Classics. Volume XX. John T. McNeill, editor. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Calvin, John. 1964. “The Necessity of Reforming the Church” in Calvin: Theological Treatises, pp. 184-216. Editor: J.K.S. Reid. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Calvin, John. 1964. “Reply to Sadolet” in Calvin: Theological Treatises, pp. 221-256. Editor: J.K.S. Reid. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Eusebius. 1890. “The Church History of Eusebius” in Eusebius. Translator: Arthur Cushman McGiffert. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Second Series. Vol. I. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Ignatius. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers. Volume I. Loeb Classical Library. Editor: Kirsopp Lake. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Irenaeus. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers. Editors: Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Ante-Nicene Fathers. Volume I. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Justin Martyr. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers. Editors: Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Ante-Nicene Fathers. Volume I. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Polycarp. 1985. The Apostolic Fathers. Volume I. Loeb Classical Library. Editor: Kirsopp Lake. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Winter, Ralph D. 1992. “The Kingdom Strikes Back: Ten Epochs of Redemptive History.”

I stand by my canard remark, but I will clarify:

1. While this essay is more nuanced than the type of apologetics used by many convertskii, it needs to be said that Calvin isn’t positing a huge fall from grace.

He is not saying that everything went to garbage in 101 CE. This is evident from his wide use of sources from Cyril to Bernard of Clairveaux. I’ll leave aside whether he interpreted these correctly (I Have my doubts), but the fact that he used them indicates from his own point of view that he didn’t think they were tainted.

2. The simplicity in the Eucharist is a fairly standard charge. Even Schmemann (Liturgical Theology) took some heat from the more conservative Orthodox because he seem to acknowledge innovation in the Eucharist.

As to the Ignatian comments about the Eucharist: ultimately these questions hinge on questions of truth. No one today, even the most Southern of Baptists, denies a “real presence,” since God is everywhere present. But once we start qualifying what we mean by presence and hypostasis and can Jesus exist outside his hypostasis, then the charge loses much of its force.

3. Mercersberg: Mercersberg was mostly rejected by the Reformed because it seemed to posit a perfect ideal form of humanity that Christ assumed which had nothing in common with an actual human existence.

Jacob,

Can you give us a definition of what you mean by “convertskii”? I Googled it and all the hits that come up are at your sites (LOL!). Is this intended to be derogatory? If you mean “convert” (from one Christian confession to another), why not just use plain English? I’m sure most of Robert’s readers are anglophones.

This is a very interesting posting. Almost 40 years ago as a graduate student I wrote an essay comparing John Knox’s and John Calvin’s views of Church History. Knox held an almost anabaptistical view that the “Fall of the Church” began right after the apostles’ death, and was largely complete by the time of Constantine, at least as regards church polity and liturgical worship; and that all was darkness until the appearance of the Lollards. Calvin was much more subtle, and indeed seems to vacillate between the two views which you adumbrate in this posting. But (IIRC) he does hold that matters were not hopeless until around, or just after, the time of Pope Gregory the Great. Moreover, in various places he expresses a very favorable opinion of the writings of St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), although not an unqualified one. Most remarkably, he seems to regard St. Augustine with unbounded admiration (compare Luther’s more mixed, and in some respects decidedly negative, views on Augustine) and goes out of his way to make excuses for what he regards as Augustine’s “slips.” One example of this is as regards prayer for the dead, which Augustine strongly commended and practiced. Calvin references St. Monica’s dying request to her son to “remember me at the altar” (which, since Augustine was not ordained at the time, meant, “remember me at the celebration of the Eucharist;” cf. St. John Chrysostom’s words about the efficacy of prayer during the offering of the “bloodless sacrifice” with the “gifts lying upon the altar”), and then goes on to comment about how superstitious mothers often have an unfortunate influence over their sons, even godly sons, and concludes that this was the case as regards Augustine’s views on prayer for the dead.

My essay was in some ways an “application” of John Headley’s subtle book *Luther’s View of Church History* (1963: Yale University Press) which argued that Luther, unlike other Reformers, refused to set a date for the “Fall of the Church,” holding that it was always falling and always being called to reform, right from the beginning; although Luther did (Headley claims) hold that it was not until after the time of Gregory the Great that the papal office became “anti-Christian,” such that the pope could be seen (in his office, but not necessarily his person) as “the Antichrist.”

I do think that Protestants tend to miss the point when arguing against tradition (as opposed to a “relationship” with God). They seem to see tradition as by definition not guided by the Holy Spirit. But then the guidance of the Holy Spirit becomes merely personal and hidden rather than corporate. Once it becomes personal and hidden there no longer seems to be anyway for use to decide “which church” to go with.

Robert, your claim, however, that there being only a small remnant not identifiable with the Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox Church is a problem seems to ignore how things have been in Biblical history with Israel (cf. the prophet Elijah in the Northern kingdom of Israel).

However, I think that losing sola scriptura is a blow to Protestant theology that is so great that one must ask, then, how the faith can be known. It seems to me that unless God preserved the faith some other way it is a damning commentary on the entire Christian faith. So, Roman Catholicism? Or Eastern Orthodoxy? Or Oriental Orthodox? Hmm . . .

Prometheus,

An example of the Remnant theory would be the Landmark Baptist movement which claims to have a lineage going back to John the Baptist. This leads to the startling claim that they, not the Protestants, are true Christians! That is why the Remnant theory was mentioned in my article. One cannot use a broad brush with respect to Protestantism. It is a surprisingly diverse movement with many exceptions. Anastasios brought up another intriguing exception to the Protestant understanding of church history, the Anglicans! I appreciate your bringing up the example of Elijah, but I would note that Eastern Orthodoxy has confessed an orthodox Christology for the past two thousand years.

Your thinking is correct. If you no longer hold to sola scriptura, then you are in an interesting place in your journey. You have left one home and are searching for a new one. The only advice I have is continue to read up on the church fathers, get a sense of how they understood and lived the Christian Faith, attend the Liturgy, and of course pray for God’s guidance!

Robert

Very interesting. I wasn’t aware that many protestants and evangelicals thought that the early church apostasized. As an Orthodox Christian living in Utah I thought that was a particularly Mormon point of view. I wonder how many other points Protestantism, evangelism, and Mormonism coincide? Fascinating article…thanks.

Depends on what you mean by “Protestant.” Historically,, the main Protestants would not have held to this view. To the degree they would have, and in keeping with their historicist eschatology, they wouldn’t have posited such a “fall” until roughly 600 AD.

Thank you Olaf, that’s good information. Why the year 600 AD? What did they find significant about that time in history?

I am loosely paraphrasing Turretin. While Gregory I was mostly a good guy, at that point, per the Reformed gloss, the papacy began to accrue to itself more and more temporal power.

I generally agree with the outlook of the older Reformed gloss, though I see the Antichrist as being more of a future entity within the New World Order nexus. It always made more sense to see the Papacy as the False Prophet rather than the Antichrist.

OA, the most verbose proponent of the AD 600 timeframe is the Elizabethan bishop, John Jewel, who made it his watershed. It allowed him to shove Gregory the Great into both camps: on the one hand he could use Gregory’s much cited reprimand to John of Constantinople that no bishop should take the name ecumenical patriarch, while at the same time damn St. Gregory in sending that blood-thirsty Augustine of Canterbury to England and destroying the apostolic simplicity of the English church.

Anglicans are pretty much the only Protestants who completely reject “Fall of the Church”; all but the most low-church/Puritanical of them argue that “We never left Rome, Rome left us” and that there’s perfect continuity between the medieval English church and the post-Reformation CoE. Whether or not this is actually true is another question.

Regarding Calvin, it’s interesting that he would quote Cyril favorably, given that Calvin’s own Christology is pretty much incompatible with Cyril’s. Calvin’s Christology is hyper-Antiochene (I. e., emphasizing the distinction/division between Christ’s divinity and humanity), verging towards Nestorianism. The fact that many Calvinists (such as Rushdoony) LOVE the council of Chalcedon and are always naming things after it (there are many Calvinist churches called “Chalcedon”, and then there’s Rushdoony’s Chalcedon Foundation) attests to this. Calvinists frequently accused their Lutheran opponents of monophystism because of their more Alexandrian/Cyrillian approach. Cyril, of course, belonged to the Alexandrian school and preferred the mia-physis formula.

Regarding Luther; is it true that he considered Eastern and/or Oriental Orthodoxy essentially uncorrupted? Unlike Calvin he wasn’t an iconoclast, and his beef with Catholicism stemmed primarily from his opposition to the Papacy and indulgences (which the Orthodox, of course, don’t have). If I’m not mistaken, he once wrote a litany of complains against the Pope, one of which is “he has excommunicated the Greeks despite the fact that there are no truer Christians than they”, or something like that. He also favorably quoted post-Schism Orthodox writers. This would imply that Luther didn’t believe in a global fall of the Church, but rather he believed only the Western church had degenerated. Jan Hus (who was the primary influence on Luther) also held Orthodoxy in high regard, as did Wycliffe (which is ironic considering Wycliffe’s iconoclasm, but then Wycliffe never set foot inside an Orthodox church, so he wouldn’t have known what their worship was like). Many of the earliest reformers and proto-reformers made reunion with the East a primary goal, but unfortunately later ones like Calvin (who threw the Orthodox under the bus in his writings) hijacked what could have become a great movement for reunion and instead redirected it into a wild-goose chase, creating their own new theological systems from scratch instead.

Thank you Anastasios. That is interesting. I’m unsure how one can be a Christian and yet believe that Christ utterly failed to establish His Church, the Body of Christ, for the better part of the 2000 years since His resurrection. That sounds an awful lot like Mormonism. Joseph Smith said something akin to it was only he who was able to establish the church. That not even Christ was able to accomplish this. I don’t understand it. However, there is much I don’t understand. Thanks again.

I’ve always wondered to what degree Calvin’s Christology was Antiochean. I know he emphasized the “distinctions between the natures,” but I have my doubts that he held to the same metaphysical outlook that the Nestorians did.

I remember reading those remarks about Hus and Wyclif. Where did you read that Wycliff was iconoclastic? I know he rejected transubstantiation, but did he write specifically on images?

Good article Robert,

I’ve thought for several years into studying Orthodoxy that BOBO (versions are legion)…is really a denial or rejection of Pentecost…the abiding presence of the Holy Spirit in the Church leading it to all Truth. Thus, Winter’s 2nd quote above jumps out:

“these children do not get exposed to all the incredible things God did with that Bible between the times of the Apostles and the Reformers, a period which is staggering proof of the unique power of the Bible!”

But Christ promised the Holy Spirit…with “unique power”…not the Bible. He did not “write” or exhort his Apostles to “write”…but to receive the Power of the Holy Spirit. It would be decades before anyone began to write Scripture…and centuries before the NT cannon was established…by a Church Council! I suspect I was once guilty of loving my printed Bible…far more than I love the presence of the Holy Spirit abiding in and teaching Christ’s body the Church!

And Olaf Axe can quip about Southern Baptists believing in the “Real Presence” of Christ at the Eucharist just like the early Fathers if he wants — like Unitarian Liberals “believe” the bible, and modern neo-conservatives “believe” the US Constitution! As EVERYONE “believes” in the Easter Bunny. LOL!

1. That Christ promised to be with his church implies…exactly what? That every council would be a priori infallible? That there would be a patrum consensus that is infallible when it is right but not when it is wrong? Christ’s promising to be with his church does not imply any of these things.

2. As to “real presence.” Did I ever say the SBC believes in the Eucharist like the Fathers? No. My point was that SBC view is no more problematic, since on their gloss they don’t have to account for how Christ’s natures can be in the Eucharist without dividing the hypostasis (which is in heaven at the right hand) or positing multiple hypostases. Remember, as both Gregory Palamas and Leontius of Byzantium teach, natures are always en-hypostasized. So if Christ’s two natures (or divine nature) is really present in a 1:1 way in the Eucharist, then there are problems.

Karen,

“Convertskii” is a term invented by a friend of mine who converted to the Antiochean church. It is meant in good fu n.

I wouuld also like to make the observation that “apostasy” is rather strong language and its unlikely that Calvin held that view (otherwise his usage of Patristic and medieval sources would be quite odd!). One can say that the early church(es) held to philosophical opinions that were more and more at odds with the earthy, Hebraic worldview. This does not mean that the church utterly fell from grace lock, stock, and barrell.

We ran into similar difficulties on this forum when we said that Calvin “dissed” the Church Fathers. Dissing is perhaps too strong a word. For example, I love reading the fathers on Christology but their treatises on angelic celibacy are some of the most poorly-argued tracts in the history of Western civilization.

Interesting article Robert. I’ve always thought in terms of formation – deformation and reformation rather than BOBO!

I bet that some form of BOBO is inevitable at least within ethnic jurisdictions: The Roman world under the Arian Constantius, Julian the Apostate, the orthodoxy of the Patriarchates that excommunicated Maximus the Confessor (and maybe Chrysostom), the Turkish-controlled Phanar, Patriarch NIKON’s open altering the liturgy and changing the Russian Church, Peter the Great’s (a Luciferian and Freemason) dismantling the Russian Patriarch, Sergianism, etc.

For Rome: the three popes at one time!, Vatican II, Novus Ordo, etc.

So when Protestants hear the BOBO charge, we’re really not too bothered. Jesus said he would preserve his church. We simply deny that this means the church will always be publicly on a hill forever kept in the faith (at least in the public and leadership levels).

// So when Protestants hear the BOBO charge, we’re really not too bothered. Jesus said he would preserve his church. We simply deny that this means the church will always be publicly on a hill forever kept in the faith (at least in the public and leadership levels). //

I don’t see that one can demonstrate that the (Orthodox) Catholic Church – in both senses of “catholic” in universality and “catholic” as in “whole/nothing lacking” in the local parish – has ever gone remotely close to BOBO – especially when one considers the faithful laity! Since the Church is the theanthropic extension of God incarnate (i.e. the body of Christ), how could it be anything but “publicly on a hill forever kept in the faith”? BOBO and the “invisible church” self-justifying for existence Reformation doctrine, is a very docetic interpretation of what it would mean to be the Body of Christ! Aren’t “bodies” by definition always physical and visible? If the Body of Christ in the Eucharist and as the Orthodox Catholic Church, is truly only a Protestant “invisible” body, how confusing and arbitrary to suddenly insist that Christ himself had a physical body!

Well, I was going by Jerome’s statement and later the treatment of Avakkum by NIKON. I reject the hypostasis of Jesus is present in the Eucharist, so that’s a non-starter for me.

// I reject the hypostasis of Jesus is present in the Eucharist, so that’s a non-starter for me. //

Yes, I realize this. You evidence the point that I was trying to make: Reformed Protestant rejection of Christ’s hypostatic presence in the Eucharist and in an infallible – visible – Catholic Church, logically leads to a heterdox docetic rejection of Christ’s possession of a physical body. St Ignatius made this observation 1900 years ago: disbelief in the hypostatic presence – in his day – was connected to disbelief in Christ having assumed physical nature.

“Consider how contrary to the mind of God are the heterodox…They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, BECAUSE THEY DO NOT ADMIT THAT THE EUCHARIST IS THE FLESH OF OUR SAVIOUR JESUS CHRIST, THE FLESH WHICH SUFFERED FOR OUR SINS AND WHICH THE FATHER, IN HIS GRACIOUSNESS, RAISED FROM THE DEAD.” (St Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Smyrnaeans”, paragraph 6. circa 80-110 A.D).

St Ignatius here states that it is heresy (heterodoxy) to deny that the Eucharist is the true crucified and risen flesh of Christ! How utterly different this is from the 16th century Reformed position!

Further to my point about the (Orthodox) Catholic Church being the visible Body of Christ, I recently used Strong’s Greek Lexicon to do a word search of “body” (soma in Greek) as in “Body of Christ” (for reference to the Church and to the Eucharist). The word number is 4983 and is used evidently 120 times in the NT. Never once – that I could find – does it refer to a metaphoric non physical/non substantial/non visible entity! I could be mistaken on this, but it would seem totally in opposition to the NT usage for “Body of Christ” to mean what Protestants erroneously claim that it means: an “invisible” Church! Indeed, all the evidence word “soma” is against to the novel 16th century self-justifying reinterpretation of “soma tou Christou”/Body of Christ. “Soma tou Christou” as Church and Eucharist would seem to indicate a necessary physical and visible presence as a minimum! Of course you’re free to believe otherwise, yet the Fathers, Scripture, and the Councils would indicate very much in the opposite direction.

***Reformed Protestant rejection of Christ’s hypostatic presence in the Eucharist and in an infallible – visible – Catholic Church, logically leads to a heterdox docetic rejection of Christ’s possession of a physical body.***

My point in said rejection is that the hypostasis of Jesus is in “heaven” (whatever that word means). If more than one Divine Liturgy is going on at the same time, then we necessarily have more than one hypostasis of Jesus.

I also view sacraments as signs and seals, so this is also a non-starter for me.

I realize I differ with Ignatius on this point. That does not bother me.

Jacob,

Since your understanding of Jesus being “in heaven” is deficient (I appreciate your admitting you don’t understand what that means, which seems clear by what you state elsewhere as well), you cannot understand that the hypostasis of Jesus, His humanity having been glorified and translated to “heaven” is, therefore, post-Resurrection and Ascension transported once again also outside of time and space (as well as remaining within it through the Holy Spirit “everywhere present and filling all things”). Is not Jesus, by orthodox Christian definition, perfectly united with the Holy Trinity? Is not the Holy Trinity, by Nature and by definition, omnipresent? Christ can, therefore, indeed be present in His entirety everywhere at once! We know that His glorified Human Body no longer has the limitations of our mortal earthly existence, otherwise He could not have appeared in the upper room without entering through the doors as the Gospels recored He did, nor appeared and disappeared at will. Is it reasonable to expect that if Christ’s glorified Body had transcended the limitations of earthly space (as the Gospels attest), it would not have also transcended the limitations of creaturely time? If not, how could He take up residence in every one of the members of His Body (which the Scriptures clearly teach He does)? Do you not understand that the Scriptures teach that the Members of the Trinity “inhabit” One Another and that where one Member of the Trinity is, there are the Others as well, and that we, the redeemed, in being deified, are destined to share in this same intimate communion with God (Luke 4:1, John 17:21-23, ) through the grace of His Holy Spirit? We certainly cannot comprehend how this is so, except to say that it is the work of the Holy Spirit’s manifestation of Christ in His Body, the Church–it is a Mystery transcending our earthly human experience. But that it is so is clear from the Scriptures’ teaching and from the teaching of the Church Fathers (e.g., St. Irenaeus) from the beginning. The Eucharist is the consummate sacramental expression of this Mystery of Christ in His Church, our “hope of glory.”

// My point in said rejection is that the hypostasis of Jesus is in “heaven” (whatever that word means). If more than one Divine Liturgy is going on at the same time, then we necessarily have more than one hypostasis of Jesus. //

Sorry but the “Reformed” view of the Eucharist you uphold is not only in opposition to the earliest Fathers who lived during NT times and spoke on the topic (like Sts Ignatius of Antioch and Clement of Rome) – but, indeed of every single Father without exception! They all believed and taught the change into the real (hypostatic) body and blood of Christ, which occurs at the Divine Liturgy/Holy Qurbana/Mass. I do agree – however – with many Protestants – of the Zwinglian persuasion – that all Protestant “Eucharists” are nothing more than a symbol however.

The “Reformed” assertion that Christ´s body and blood can´t be omnipresent is – again – another ahistorical novelty of the Reformation. I´m puzzled that the Reformed can believe that the divine nature of Christ allowed him to work miracles, walk on water, raise the dead, etc – but that it couldn´t allow him to become omnipresent in his one united person? Why is God limited in only communicating certain attributes – and not others – to the physical nature? This doesn´t lead logically to a “confusion” of the natures any more than in theosis we become a fourth member of the Trinity! Wasn´t the manna in the wilderness a type and foreshadowing of the Eucharist (John 6:51), which daily appeared as a miracle? St John Chrysostom says of this in the Divine Liturgy,

“The Lamb of God is broken and distributed; broken but not divided. He is forever eaten yet is never consumed, but He sanctifies those who partake of Him.”

Most importantly – laying aside the fact that the Reformed don´t really believe in the hypostatic union in the historical Christian sense (i.e. “original guilt/corrupted nature” mean that Christ truly didn´t assume the entire human nature) – your assertion (about Christ´s body and blood remaining in heaven) is vacuous since we believe that we, rather, are raised up to heaven in the Divine Liturgy (rather than him being “pulled down” to earth)! All ancient Liturgies have the “Sursum Corda”/Anaphora, in which we are literally brought up to the reality of heaven. So, even if your (deficient) and novel insistence that Christ´s body and blood can´t “leave heaven” were true, it still wouldn´t follow logically that we couldn´t all eat his (hypostatic) body, blood, soul, and divinity because we are lifted up to him in the realm of heaven.

Thank you Robert for addressing an issue that I think makes Calvinism and most of Protestantism untenable. If the Great Apostasy occurred shortly after Jesus died, I think Christianity itself is unattractive and self contradictory. I cannot imagine how one could read the Patristic witnesses and see how they suffered for that witness and conclude that they were universally in error.

I also appreciated this encomium about Jarislov Pelican. http://danutm.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/wilken-robert-l-jaroslav-pelikan-and-the-road-to-orthodoxy.pdf

I have always appreciated Professor Robert Wilken. I found this particularly gracious and irenic. Would that he were Orthodox.

Jacob,

You asked, “That Christ promised to be with his church implies…exactly what?” is a classic problem of Sola Scriptura. There’s no dispute between us on what the Scriptures “Say” here. Christ promised to send the Holy Spirit to the Church, and to lead them into “all Truth.” Now, you have declared that it can NOT mean “a priori infallibl[ity]” nor a “patrum consensus that is infallible when it is right but not when it is wrong.” Thus we dispute what this Scripture “means/implies” to the Church of Christ in history. You have your opinion, and the Orthodox have what the Apostolic Fathers have judged it meant for over two thousand years.

The Holy Tradition that grew up around the Apostles strongly supports the presence of Bishops given the to rule from Christ. Phillip spoke to the Ethiopian Eunuch out of that tradition in explaining the Scriptures. Perhaps the Bishops rule is more like Fathers, Coaches, Bosses…fallible humans with real authority to rule and declare what’s what. They quickly had Icons, Vestments, believed in the Real Presence of Christ at the Eucharist contra the symbolic/spiritual manner Calvin and other reformers articulated. When they began to write Scripture, they often exhorted their disciples (Timothy & others) to follow, guard and keep their Tradition already existing. As with Fathers, Coaches and Bosses given authority to rule, the language of “infallibility” is simply unnecessary for their authority to be real, or for their commands to be obeyed. This is especially so when the Bishops gather together to resolve disputes in the Spirit of Acts 15 in Church Council…as cannon law.

This was how the Church functioned in history for over a thousand years. There was no dispute about it until Rome left, asserting their Bishop/Pope had supreme authority over all Bishops, Priests, Deacons and Churches. They still do. The Orthodox object saying it had never been so. You reject both of these historic loci of authority for – your own studied but ultimately independent opinion via ‘sola-scritpura’ within a very selective Reformed Tradition? You reject Apostolic Holy Tradition as having no moral or historic claim upon your obedience and embrace BOBO. The Holy Spirit lead me away from this ahistoric independent posture. I came to believe that the Holy Spirit’s Tradition in history does indeed have moral and Spiritual claim upon me, to the point of me becoming Orthodox in my heart and mind…and happily submitting to the Church.

This is the big picture of what’s going on here. You often revel in the minutia of this Father differing here and there from that one. But this only obfuscate what’s really at issue here. Christ’s promise in Scripture to give the Apostles the Holy Spirit to lead the Church into all Truth is either an empty promise that ultimately means some form of BOBO to the Protestant mind or practice – OR – it means what the Bishops of the Orthodox Church have always believed, that Christ intended to comfort the Church with an ever-present Holy Spirit as he draws men to Himself in His body, the Church. Lord have mercy.

It also occurred to me as I was reading this thread that even where there have been worldly and corrupt Bishops/Patriarchs (or those whose spiritual authority was compromised by political manipulation of corrupt rulers), there has never failed in every generation somewhere to be Orthodox Bishops (and laity) in the succession who remained faithful (many on pain of torture, exile and death). It is these Bishops whose decisions in the Ecumenical Councils the contemporary Orthodox churches continue to uphold as the standard of dogma and practice and the interpretation of Scripture. So, yes, in the big picture, a historic, identifiable Body of believers in direct dogmatic and physical succession to the earliest believers exists in the contemporary Orthodox churches–even while a definition of what this Body means by “the Church” is not a simple one-to-one sum total of all her formal members throughout history.

***there has never failed in every generation somewhere to be Orthodox Bishops***

I agree. That also sounds a lot like BOBO. Jerome said the entire world was Arian at one time. Maximus was told that the entire Roman and Orthodox world believed differently than he, and he was disciplined as outside the faith. This right here completely vindicates the BOBO theory.

How so? If St. Maximus or St. Athanasius (among others who most certainly have gone unnamed) were arguing for orthodoxy against whatever numbers, being in the majority or the minority, then BOBO is certainly not vindicated. What would vindicate BOBO would be that noe body was around to argue against heresy because all had fallen into it. “Athanasius against the world” wasn’t really “just Athanasius”. He was just a deacon at the time. The then current bishop of Alexandria, whose name fails me at the moment, was also an opponent of Arianism, among a myriad of others. I’m really not seeing how this vindicates BOBO, or even sounds like it. Could you please elaborate? I’m confused by your statement.

John

For one, I was simply going by Jerome’s statement and assuming it to be true. Never minding the big difficulties it poses for the Semper ubique claim at the moment, I was simply saying that if the whole world was Arian, pace Jerome, then it seemed to appear, to go with the rather untenable BOBO model, that the light blinked “off.”

I question your acceptance of your own assertion, “Maximus was told that the entire Roman and Orthodox world believed differently than he” since Pope St Martin I – Patriarch of Rome and first among equals – was on the side of Maximus prior to his death in 655 (just a few years before Maximus’ trials in 658 and 662). Also, Pope St Theodore I -two decades before – vigorously had opposed monothelitism! Certainly, the Orthodox west – aside from Pope Honorius I – didn’t support monothelitism: hence, no example by Protestants of BOBO can be leveled realistically against the undivided (Orthodox) Catholic Church! Is there evidence that the entire Pentarchy fell into monothelitism at the same time? Moreover, it should be asked whether the laity – east and west – ever found this to be a popular belief. As you know, we don’t consider a council to be Ecumenical if opposed/not accepted by the laity!

***“Maximus was told that the entire Roman and Orthodox world believed differently than he” since Pope St Martin I – Patriarch of Rome and first among equals – was on the side of Maximus prior to his death in 655 (just a few years before Maximus’ trials in 658 and 662). ***

I know Pope Martin sided with Maximus. I was just going by the trial records of Maximus.

***even while a definition of what this Body means by “the Church” is not a simple one-to-one sum total of all her formal members throughout history.***

Again, I agree. That’s what Protestants call the invisible church. 😉

“invisible church”

Except, as far as I understand the origins of this teaching (in the WCC?) as it is understood among Protestants today, no one communion of Christians is understood in its polity, dogma, and Eucharistic practice to be entire in its own manifestation of catholicity–whereas in Orthodoxy, that is most definitely not the case. Therein it seems to me lies a significant difference. My experience in the Orthodox communion is that, despite the presence of sin and sinners in the Body (just as in my former Evangelical circles), I no longer have the nagging feeling there is something missing within the Church in terms of her dogma, vision of Christ, understanding of the sacramental life and spiritual disciplines. I no longer find explanations of the nature of the Church and of salvation in Christ that conflicts with my actual experience of those things (meager as this may be).

***Thus we dispute what this Scripture “means/implies” to the Church of Christ in history.***

If you believe that then you will have to explain the Robber Baron’s Council, Heira, NIKON+, New Calendraism and a host of very fallible yet evidently normative situations. That’s simply my point.

***You often revel in the minutia of this Father differing here and there from that one. ***

I did not offer minutae (although one must point out that the Patrum consensus is built off this very minutiae), but normative situations: Nikon changed the structure of Russian Orthodoxy. Even modernist Orthodox like Paul Meyendorff concede this point. The liturgy changed decisively.

***The Holy Tradition that grew up around the Apostles strongly supports the presence of Bishops given the to rule from Christ. ***

I have no problem with this (besides the circular nature of the argument). I’m fine with bishops as long as they don’t have the neo-Platonic baggage of hierarchical mediation (see False Dionysius’s works). Before the accretion of neo-Platonism, bishop and overseer–and I acknowledge the presence of bishops–functioned administratively and did not mediate higher levels of reality.

***You reject both of these historic loci of authority for – your own studied but ultimately independent opinion via ‘sola-scritpura’ within a very selective Reformed Tradition? ***

You mean learning about four languages and reading roughly 25 different Reformed systematic theologies spanning five centuries? Selective? Anyway, you used your own private judgment to adjudicate the claims of Orthodoxy and Rome.

***Christ’s promise in Scripture to give the Apostles the Holy Spirit to lead the Church into all Truth is either an empty promise that ultimately means some form of BOBO to the Protestant mind or practice***

And here is what I have been saying for 18 months: you have no non-circular method of attaining beforehand what is valid tradition and which isn’t. And this is further complicated by the situations I’ve listed above. I simply dispute that Christ promised full infallibility to the church and that the church would be forever prominent on the forefront in said infallibility. There is no way you can infer that from his words.

Speaking of canards, the “private judgement” concerning Rome and Orthodoxy is certainly one.

Probably, but if your tired of hearing it then maybe Orthodox guys should return the favor and find a new argument.

Given this blog posting most should wonder where the solid protestant argument is — that the Holy Spirit that came at Pentecost really did desert the Church at large (Blinked OFF) maybe more than once, and allowed not a Heretic here and there, or one solid Father with a disagreeable idea) but the Church as a whole, to Fall into rank Apostasy. Let see exegetical, theological and historic arguments for that. (on your Blog, you can link to it).

I. Never. Said. The. Church. Fell. Into. Rank. Apostasy.

I said philosophical ideas slowly gained in the church which ultimately had a deleterious effect (which in case delegitimizes the church).

Jacob,

When I quote you I use “your words” in quotes. But the contrary argument and implications are implied…and we await an argument that proves BOBO is in fact an exegetical, theological and historic protestant reality! 🙂 Otherwise, Robert’s article above stands…with only tangential minutia quibbles against it.

I just ran a word search of “apostasy” on this page. I never used it. In fact, the only time I did use the word “apostasy” was to say that such language is not my position. I don’t know what else to say.

Perhaps we can start over. I’ll just ask one question:

1) Did Christ promise that every pronouncement (or position) of the church would be infallible?

Karen,

***. Is not Jesus, by orthodox Christian definition, perfectly united with the Holy Trinity? Is not the Holy Trinity, by Nature and by definition, omnipresent?***

I have no problem affirming that, but you do realize you just affirmed what is called the “extra-Calvinisticum?”

But leave that aside, if Jesus’s body is everywhere, then the word “body” has no real meaning and you need to abandon Chalcedon. If the propria of deity are transferred to Christ’s flesh, then Christ’s flesh is no longer flesh. (I do realize that the Fathers at Chalcedon held to a deification soteriology and a real communicatio. I think they are inconsistent on a number of points, though).

Clearly, I’m no expert, Jacob, but I suspect Scripture’s teaching about the nature of the human body as it is glorified by Christ, does not conform to our human expectations and scholastic definitions of “body” (the Apostle Paul’s discussion of the relationship of the resurrected, glorified human body, to the mortal human body comes to mind. As the plant, leaves and fruit transcend the bounds of the seed, yet are still related to the same, so the glorified “spiritual body” of a redeemed human being transcends the bounds of the mortal). I’m Orthodox, therefore, I have no problem acknowledging the limitations of the cataphatic statements in the Scriptures and their potential to result in distortion–especially when they are understood in a very limited and merely earthly overly literalistic human sense and not balanced by apophatic statements about God’s nature. From what I have learned, the doctrine of Divine “simplicity” means that we must acknowledge both apophatic theological statements about what God is “not” (or what He is “beyond”) because He radically transcends our human experience as well as the cataphatic statements from Scripture about what God is in concrete, specific and personal terms as both being true–the latter in a real, experiential and yet at the same time limited analogical sense (in terms the capacity of human language to capture and express this truth of God’s nature).

This “both/and” paradoxical nature of the fullness of Orthodox Christian teaching about the nature of God and of humankind’s redemption as “theosis” does tend to elude nice, neat, consistent Scholastic-style explanations. But a “God” completely reducible and amenable to such explanations would be a “God” worthy of neither wonder nor worship it seems to me.

***nature of the human body as it is glorified by Christ, does not conform to our human expectations and scholastic definitions of “body” ***

One of the problems, though, is that when the councils spoke of body, they had in mind a real humanity. This is complicated further by the fact that Orthodoxy prides itself on realism and forms, and that Christ took upon a universal human form. The problem, however, is that the universal human form–especially as it is instantiated in time and space–isn’t ubiquitous.

When I wave my arm through the air, I am not touching Jesus’s body.

Is “real humanity” defined by our own fallen earthly experience of this, or by Christ? In Christ, is not our humanity transfigured and fulfilled to surpass its earthly, fallen temporal limitations?

I’m not suggesting, obviously, that when you wave your arm though the air, you are “touching” Jesus’ Body. But then I wouldn’t say that you are thus waving your arm through the Spirit of God either, even though I believe the Scripture’s teaching that “in Him we live and move and have our being.” It is perhaps more accurate to say it is the presence of God (by His energies) at every moment in and under and around every molecule in your body and sustaining the molecules of the air which surrounds you that allows there to be air surrounding you and a you who has an arm to wave through it. I believe in the omnipresence of God, but I am not a pantheist (or even a panentheist). What I am saying is the Lord Jesus can make Himself personally and particularly present in His entirety to all of us at the same time if He so chooses in much the same way as He could multiply the loaves and fishes to feed the multitudes when He ministered in His mortal Body on earth. (My understanding is that the Gospel of John is organized according to 1st century catechismal themes, and the stories of Christ multiplying the bread were used in teaching about the nature of the Eucharist.)

eThe glorified Christ is no longer limited by temporal realities (crass materiality) in the same way as He was while in His mortal body when He accommodated Himself in the Incarnation to our fallen mortal human state (and even then, as His miracles reveal, in obedience to the will of God and by the power and presence of the Holy Spirit, He exercised His Lordship over the laws of nature in a way that defies materialistic and naturalistic explanation). In His glorification, He takes up all His prerogatives and powers as God once again, even though He also eternally retains His humanity in its glorified state.

So, when the Lord Jesus makes Himself present to you or to me in whatever way He chooses to do this, it is all of Jesus Who is present, even if this is not always in a material way as in the Eucharist. This doesn’t mean if He happened to make a full material appearance over at my house, He couldn’t also simultaneously do the same at yours. 🙂 At least, this is how I understand some of the implications of the Scripture’s teaching.

***This “both/and” paradoxical nature of the fullness of Orthodox Christian teaching***

Once you start talking “paradox” and mystery, anybody else can do the same. So if there is something troubling about Calvinism, I can say, “It’s okay. You just hae to understand the mystery of it all.”

Of course, I grant there is mystery to the Christian faith (though when the Bible speaks of mystery, it is always of mystery being revealed, not hidden).

Okay, I’m just going to “think out loud” a bit about the implications of God’s having “revealed” mysteries.

First, it seems to me “understanding the mystery” is a bit of an oxymoron to an Orthodox way of thinking. 🙂 “Accepting/embracing/experiencing” the Mystery would be more like it. Certainly, the Mystery of God’s plan of salvation and His nature is “revealed” in its “fullness” the Incarnation, etc., of Jesus Christ. Does that mean everyone who genuinely encountered Christ in the NT had that Mystery fully revealed to them? If so, in what sense? If not, what made the difference between those who rightly discerned the Mystery standing before them in the Person of Christ and those who didn’t?

Whatever else God’s “revelation” to us means, it clearly means something of the truth of Christ can be potentially demonstrated to, and concretely experienced by, human beings. But does this mean what has been revealed in Christ can be comprehended and fully communicated in explanations and propositions of human persuasive logic and language and that others can be brought into the Mystery solely through those means? 1 Corinthians 1:18-2:16 would seem to me to indicate not. Even more to the point, perhaps, does this mean the language we use to communicate with others about such an experience is likely to be intelligible to someone who has no such experience? In fact, the deeper you go into the Mystery of Christ, the less it seems to me this is likely to be true. If we reflect about the fact that of the NT only the Gospels record what was to be proclaimed to the uninitiated as well as believers, what might this suggest? In contrast, the Epistles as well as Revelation were written only to the Churches, those initiated and sacramentally incorporated into the local Christian communities under the apostolic authority, who had experience of Christ.

Even though I think you and I would agree we can make theological statements about God based on Scripture and its explanation in the Fathers that are true as far as they go, where we perhaps differ is how far we believe such theological explanations in human language ought to be able to be stretched. My conviction is that such theological explanations have to be understood in the context and limitations of the immediate concrete context in which they arose and are likely to become misconstrued and distorted when dragged into the realm of abstract theoretical theological formulations that arose in a completely different context. Unless, we have some concrete experience of the context in which such discussions arose, it is unlikely we will properly interpret and apply the theological language boundary markers placed around the Mystery in that context to guard its truth.

Olaf,

In light of the current conversation, I guess I would ask how one knows what to believe in order to be a Christian. It seems pretty clear historically that Christianity was meant to be taught in a community setting. How does one decide which texts are authoritative without a community which represents the faith properly? And if there is a faith community that can authoritatively transmit the text of the faith, how can one divorce that text from the community. Your best argument so far, I agree, is found in the fact that there are at least two ancient traditions from which to choose . . . and I agree that one has to use one’s own judgement/reason to arrive at which is true. Using one’s own judgement is always going to be the case in a search for the true faith. But it seems to me that theoretically speaking, the traditional approaches have better justification than sola scriptura. A third option, of course, is to be convinced that the person of Christ is accurately portrayed in the gospels and therefore approach the faith from a purely historical perspective, using the earliest evidence for Christianity to reconstruct the faith, judging the canonical documents with the same historical rigor that one would give any other document. Personally, I see problems with all three views . . .

*** I guess I would ask how one knows what to believe in order to be a Christian. It seems pretty clear historically that Christianity was meant to be taught in a community setting. How does one decide which texts are authoritative without a community which represents the faith properly?***

I’ve answered this about a dozen times: I have no problem looking to the church for guidance. I don’t see how one can make the logical leap that this means the church is ipso facto infallible over my soul in theological matters. At least Rome is honest and consistent on this point. I mean, if I am walking down the street and need to find directions to the liquor store, I will certainly ask Willie the Wino for help. Does that mean he is infallible on which wines I should imbibe?

***But it seems to me that theoretically speaking, the traditional approaches have better justification than sola scriptura. ***

And if by “sola scriptura” you mean the stuff that passes on this board, yeah, it’s problematic. But the guys on this board have steadfastly refused to interact with the Protestant champions on sola Scriptura: Turretin, Polanus, Richard Muller, etc.

Well, I’m glad that you have a better “sola scriptura”, but you still haven’t answered how you know which Christian community to believe on the content of the canon. There are different ones . . . and on top of that there are “Christian” communities who have radically different views of what writings are scripture. No need to be belligerent. I honestly have not heard a good explanation of how a Protestant is to determine its authoritative writings. Also, I have not heard a good explanation of how one can go to a faith that says, “we believe x, y, and z and our scriptures are such-and-such” and then take their scriptures and tell them that their faith is all wrong (I know you will quibble with the word all). Of course I do realize that the reformers were really saying that most of the Catholics of their day were departing from tradition rather than saying that they would just take what they wanted piecemeal. And I do agree that the scriptures should be able to critique the believer. I just don’t see sola scriptura as viable inasmuch as anything like it was impossible until an agreed upon “canon” existed. Of course there were writings that were authoritative early on, but others that were not.