Folks, Today’s posting contains Gabe Martini’s excellent response to Peter Leithart. I will be uploading my response to Rev. Leithart shortly. Robert

Are conversions to Orthodoxy tragic?

This is a continuing notion from Leithart and other, similar Protestants, who have adopted certain aspects of the Catholic tradition while refusing to adopt the fullness of the Body of Christ. This it not to say (at all) that Dr. Leithart is not a Christian, but that his approach to Christianity remains bodiless—an adoption of ideas and theories, but not the living and Spirit-filled community that has embodied such ideas and theories.

In his latest post at First Things, Leithart laments about “cross-Christian conversions,” naming them “tragic.”

Leithart does not deem these tragic necessarily because they are to the detriment of the convert themselves, but because the “logic behind some conversions” is flawed. According to Leithart, the quest for “the true church” is such flawed logic, and the “assumptions” behind such a movement are nothing short of “un-Christian.”

These are bold claims, especially from those who repackage Patristic theology for an audience under-exposed to both Patristics and the Catholic tradition. But, I digress. The real point of responding to this assertion of “tragedy” is that it misses the mark in a number of important ways.

First, Leithart claims that seeking out the true church is un-Christian. He explains:

Apart from all the detailed historical arguments, this quest makes an assumption about the nature of time, an assumption that I have labeled “tragic.” It’s the assumption that the old is always purer and better, and that if we want to regain life and health we need to go back to the beginning.

While many apologetics of Orthodoxy (and Rome) are centered around returning to the “original Church,” this is not a linear movement. Holy Tradition is not “older is better,” and our Tradition is not a lifeless stack of books, but the continuing life and work of both Christ and the Holy Spirit in Christ’s one, holy Body.

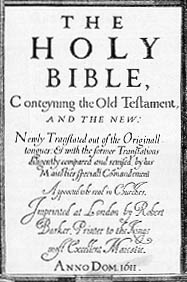

In fact, there is nothing more Deistic or backwards-facing than classical Protestantism, with sola scriptura and the perspicuity and self-sufficiency of the (Protestant canon of the) Bible. Sola scriptura claims that God—through his prophets and apostles—has left us a set of books by which one is to both understand and determine everything regarding faith and life. But the way to interpret this set of books was not included, and no interpretation is without subjectivity, nor is it the result of osmosis.

As a result, hundreds of denominations or new, individual church movements are started every year. Despite the claims to perspicuity, no two people within Protestantism agree on the right interpretation of any given sets of verses, and this even within their own, segregated, confessional communions. Leithart understands this very well, himself having been put under scrutiny by his own presbytery on a number of occasions, with each side talking past the other regarding the proper interpretation of both the Bible and the Westminster Standards.

On the other hand, the Orthodox faith teaches that we are not abandoned by God with either a single set of books (the Bible) or an old, static thing called tradition. We are not always looking back, but are instead transformed through the Body and Blood of Christ to a communion that transcends both time and place.

In the Eucharistic fellowship of the Church, we are ever-united with all the Saints of history, both past and present. Our orientation is eschatological, and eschatology is not merely “the future,” in a strictly linear sense. This is nowhere more pronounced than in our celebration of the Eucharist, which is an event that points the faithful towards the east—not merely towards Eden or the beginnings of a nostalgic faith, but towards the great wedding feast of the Lamb. This is played out not only in our written tradition and services, but also in our iconography of the Mystical Supper, which shows both Jesus and the apostles not in a dingy upper room of first-century Palestine but at the table of the wedding feast in eternity.

We certainly believe that the apostolic Church is the source of life and health for the faithful Christian, but this is not a return to “the beginning,” but rather an adoption into a timeless family. A family that is oriented towards the east (a redundancy, I know); towards the second coming and the culmination of all things in Christ (which paradoxically restores us to a unity with God found heretofore only in Eden).

Our tradition is holy, since it is the tradition of the Holy Spirit. This means that it is grounded not in a place of the past, but in the dynamic life of the Life-giving Trinity. This is an essential aspect of the doctrine of the Communion of the Saints, as well: “Neither death nor life, nor angels nor principalities nor powers, nor things present nor things to come … shall be able to separate us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom. 8:38–39).

Leithart continues:

Truth is not just the Father; the Son – the supplement, the second, the one begotten – identifies Himself as Truth, and then comes a third, the Spirit, also Truth, the Spirit of Truth. Truth is not just in the Father; the fullness of Truth is not at the origin, but in the fullness of the divine life, which includes a double supplement to the origin.

Despite the appearance of Sabellianism, and a denial of orthodox triadology, I think I understand what Leithart is getting at here.

The tradition of the Church has borne a perspective that is more nuanced than Leithart appears to allow. The earthly bulwarks of our faith (throughout the centuries, and not just in the “early Church”) have pointed to a Trinity that ismonarchical, with the Father as “origin.” For example, the Father begets the Son, and the Spirit proceeds from the Father (in eternity). Still, Leithart rightly notes that truth is not only of the Father, but is also an essential aspect of both the Spirit and the Son. What’s important to emphasize here is that our Tradition originates and rests in the life of God himself; in the life of the Holy Trinity. Not just the Father, but the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Their roles in both revealing and preserving this Faith through synergy with the Church varies according to the divine person, but we must be careful not to conflate the persons for the sake of flawed arguments.

Leithart concludes:

History is patterned in the same way. Eden is not the golden time to which we return; it is the infancy from which we begin and grow up. The golden age is ahead, in the Edenic Jerusalem.

And the church’s history is patterned in the same way too. It’s disorienting to think that we have to press ahead rather than try to discover or recover the safety of an achieved ecclesia, disorienting because we can’t know or predict the future. But it’s the only assumption Trinitarians can consistently make: The ecclesial peace we seek is not behind us, but in front. We get there by following the pillar of fire that leads us to a land we do not know.

Orthodox Christians do not believe in a mythical “golden age” of the Church. Our hagiography makes this more than plain, as we recount one exile of a Saint or one new heresy after another. What we do believe in, however, is the continuing presence of the life and light of God in the Body of Christ. Because of this fact, we know that the Church is the true community and family of God. It is not a future reality to be anticipated, but neither is it a nostalgic idea of the past. It is a continuing, apostolic mission of God’s people, transformed and recreated into the image of Christ through the passage of time. When we face the east in worship (per St. Basil the Great in On the Holy Spirit), we are facing both Eden and the glorious and second coming. Leithart bifurcates along linear projections, when it is both inappropriate and even impossible to do so.

He is right in saying that we follow the “pillar of fire” as the Church, but this pillar is within each of us. It is not a distant figure that has left us only a book and a few thousand years in order to figure everything out. It is a personal witness and indwelling in the Body of Christ that warms and guides our souls towards the kingdom; a kingdom that can, in fact, be within each one of us in Christ (Luke 17:21).

So while Leithart brings up a few important concepts in this short argument against conversions to Orthodox-Catholic Christianity, he misses the mark when it comes to not only understanding Holy Tradition and the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church, but also limits this experience of the Church to a single direction, where no such limitation is warranted.

Conversion to the one, true Church is not tragic; it is a journey home. And this home is not found in any single point in time, but transcends all such limitations, being the very Body of the Eternal One.

Gabe Martini has a BA in Philosophy from Indiana University and serves as a subdeacon at Saint Sophia Greek Orthodox Church in Bellingham, WA. He is the editor-in-chief of On Behalf of All and is a Product Marketing Lead for Logos Bible Software.

Recent Comments